The Messed Up History Of Native American Boarding Schools

Although boarding schools for Native American children in the United States still exist, they're a far cry from their original iteration. The first Native boarding schools were created during the 19th century and for over 100 years, they became another arena of forced assimilation and genocide.

Parents were coerced and intimidated into allowing their children to attend boarding schools, and if parents continued to refuse, children were often kidnapped. Children were "hostages taken to pacify the leadership of tribes that would dare stand against U.S. expansion and Manifest Destiny."

Hundreds of thousands of Native children were forced into such boarding schools. It's estimated that thousands lost their lives within the walls, but it's impossible to know exactly how many children disappeared over the years. Many tribes have sought to reclaim their lost children, but "there has been little response from federal officials, who say the requests are nearly impossible to fulfill." This is the messed up history of Native American boarding schools.

The first boarding schools

The College of William & Mary was the site of one of the United States's earliest efforts to convert Native people. According to William & Mary, it was believed that if Native children came to the Indian School, "they could be trained in British ways" and then returned to their communities in order to spread what they'd been taught.

However, many Indigenous tribal elders thought that the school was "nothing more than an elaborate ruse" designed to kidnap and enslave. As a result, few Native groups allowed their children to attend the school and sometimes sent those they'd captured to the school instead.

From 1753 to 1755, eight Cherokee students attended William & Mary. But 1756, Gov. Robert Dinwiddie wrote a letter to Cherokee leaders complaining about the students. "The Young Men that came here for Education at our College did not like Confinement, and, in Course, no Inclination to Learning. They were too old. If you sh'd think proper to send any, they sh'd not exceed the Age of 8 Years."

In "Chemawa Indian Boarding School," Sonciray Bonnell writes that by the 1860s, there were at least 48 different reservation day schools, along with missionary schools, aimed at "civilizing" Native children. However, according to an Indian agent in 1878, allowing Native children to spend a majority of their time with their families and communities "makes the attempt to educate and civilize them a mere farce."

Henry Pratt's social experiment

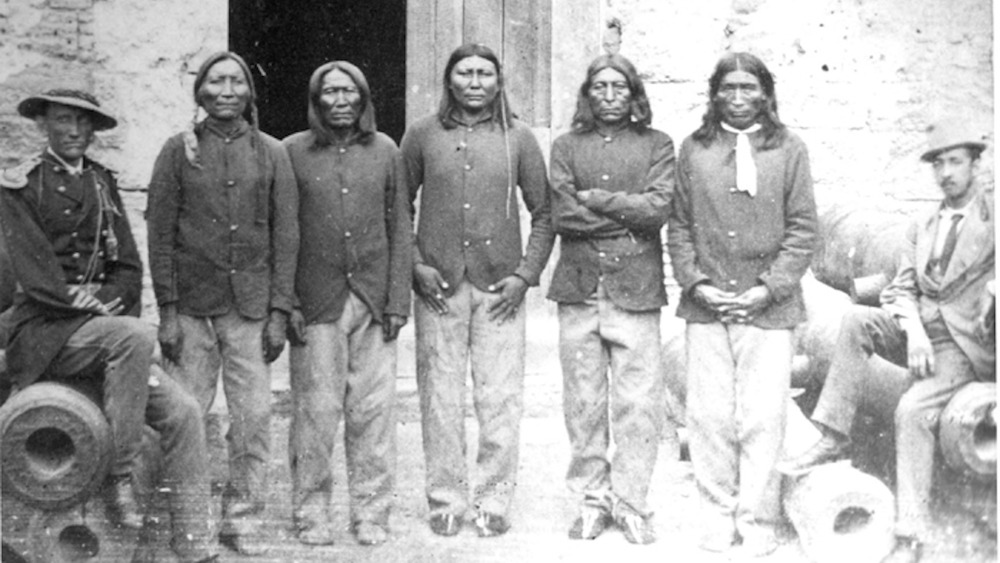

In 1875, Gen. Richard Henry Pratt was in charge of overseeing Native prisoners of war, but although his job entailed only transportation and incarceration, he had also decided to "reform" them. Many of the POWs under his charge were already dying during their transport to Florida and subsequent incarceration "from humidity, exposure, harsh treatment, and prolonged confinement."

In "Removing Classrooms from the Battlefield," Daniel E. Witte and Paul T. Mero write how Pratt forced the Native POWs to wear military clothes and cut their hair. He also forced them to learn English, follow strict military regimes, and attend church services. The Ziibiwing Center notes that this social experiment was initially conducted on Apache POWs, but Pratt soon applied it to all the various Indigenous tribes at Fort Marion once he realized that it was easier to affect peoples' behavior if he mixed different tribes together and applied a "divide-and-conquer strategy" against cultural resistance.

While some of the POWs survived Pratt's experiment, others "were severely traumatized by the experience and committed suicide."

And Pratt wasn't finished. He decided that "the paradigm and tactics he had refined for adult military Indian POWs could accomplish the perpetual economic and cultural assimilation of non-criminal civilian Indian children [original emphasis]." After briefly lobbying Congress, Pratt received permission to build an off-reservation boarding school in an old army barracks.

Creation of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School

Richard Henry Pratt founded the Carlisle Indian School in 1879 in an abandoned military barracks in Carlisle, Penn. According to the University of Washington, Pratt's reigning philosophy at the school was "kill the Indian, save the man." Although Pratt wanted to recruit children from Indigenous groups that he had experience with, such as the Cheyennes, Comanches, and Arapahoes, the U.S. government insisted that Pratt should convince the Sioux instead.

While some families allowed their children to go to Carlisle, when Siŋté Glešká (Spotted Tail), a Brulé Lakota chief, went to visit during their first year, he immediately brought his own children back home because he "did not approve of the erased Native culture or the fact that Pratt was, in his view, turning the students into soldiers with all the drilling."

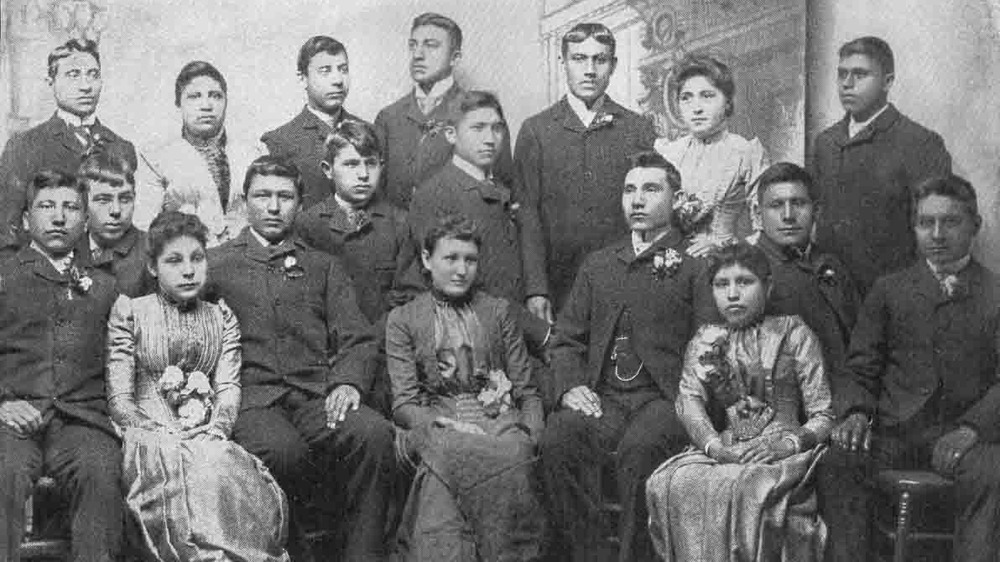

Like the POW camp, the Carlisle school was run like a military camp. Strict schedules and uniforms were enforced, genders were separated, and corporal punishment was practiced. And following Pratt's model, several other off-reservation boarding schools were soon established across the country.

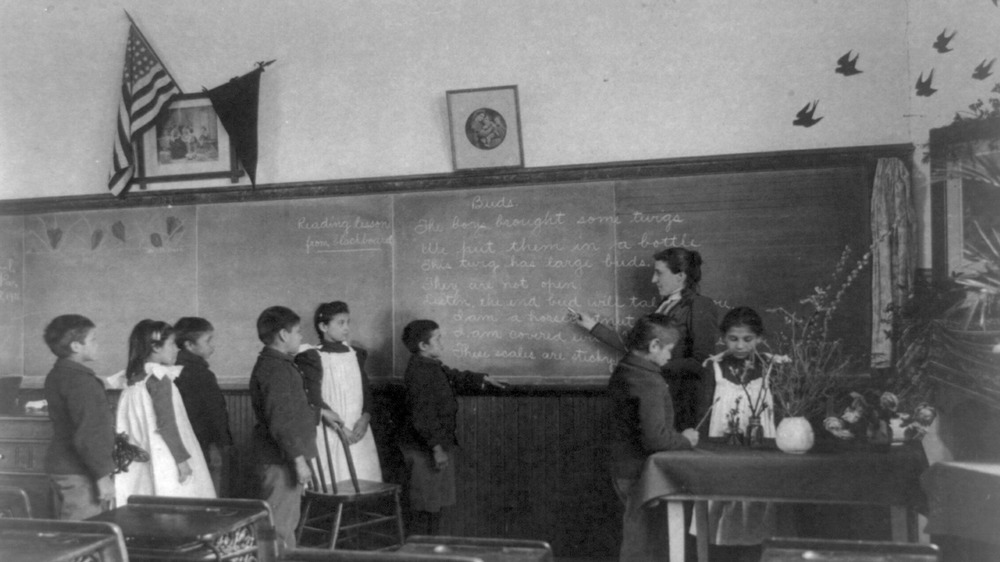

Assimilation through total immersion

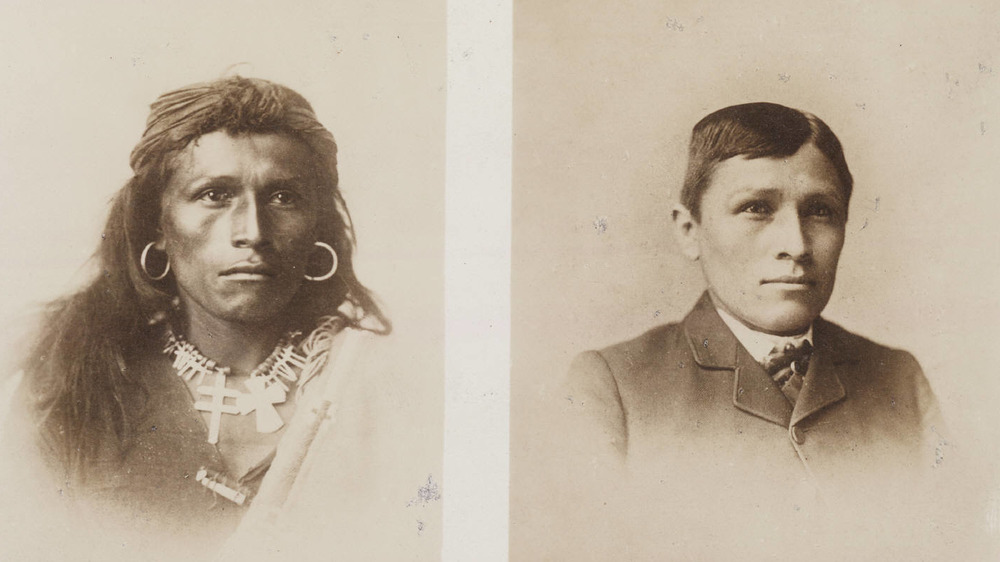

Boarding schools tried to cut every tie that a Native child had with their culture. Students from 5 to 18 had their hair cut, were forced into Victorian dress, and were forbidden from speaking their Native languages. Communication was only allowed in English, even if the child didn't know it. And according to The Atlantic, "contact with family and community members was discouraged or forbidden altogether." Any belongings that the children arrived with, including "blankets, ornaments, and jewelry," were also confiscated.

The Ziibiwing Center notes that many didn't see their parents or their family for years on end, spending their entire childhood in the Native boarding school system. During school breaks, Indigenous children were "hired out to white families," a practice that claimed to help them learn different skills. But in reality, this program was incredibly exploitative, and children were used as a source of domestic or agricultural labor.

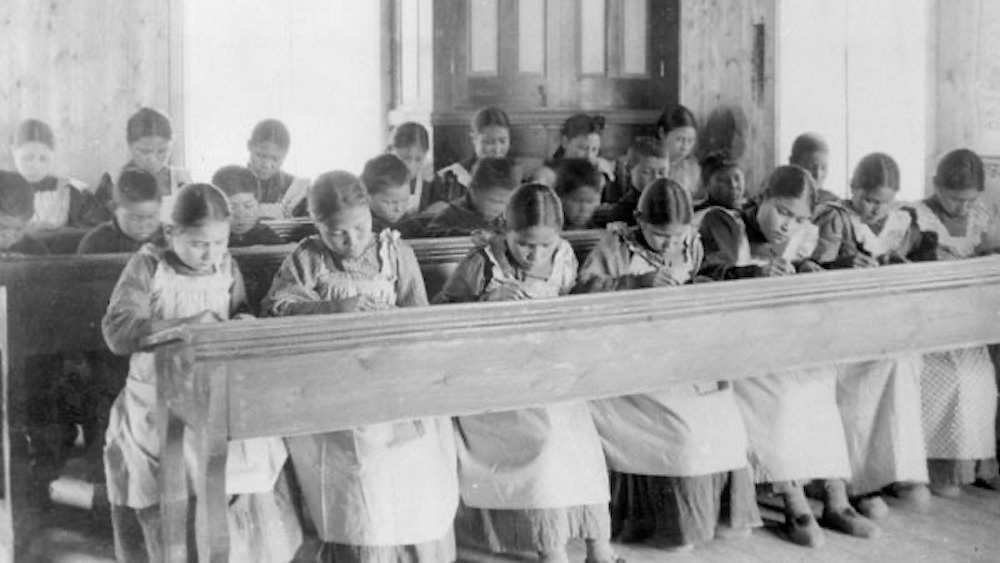

Children were forced to convert to Christianity and encouraged to abandon their native practices and traditions. According to "Boarding School Blues," edited by Clifford E. Trafzer, Jean A. Keller, and Lorene Sisquoc, school administrators also forced children to choose English Judeo-Christian names to use instead of their names in their native languages. Many of these schools ended up being funded by the Civilization Fund Act of 1819, which had tasked Christian missionaries and other "capable persons of good moral character" with introducing Native children to "civilized" habits.

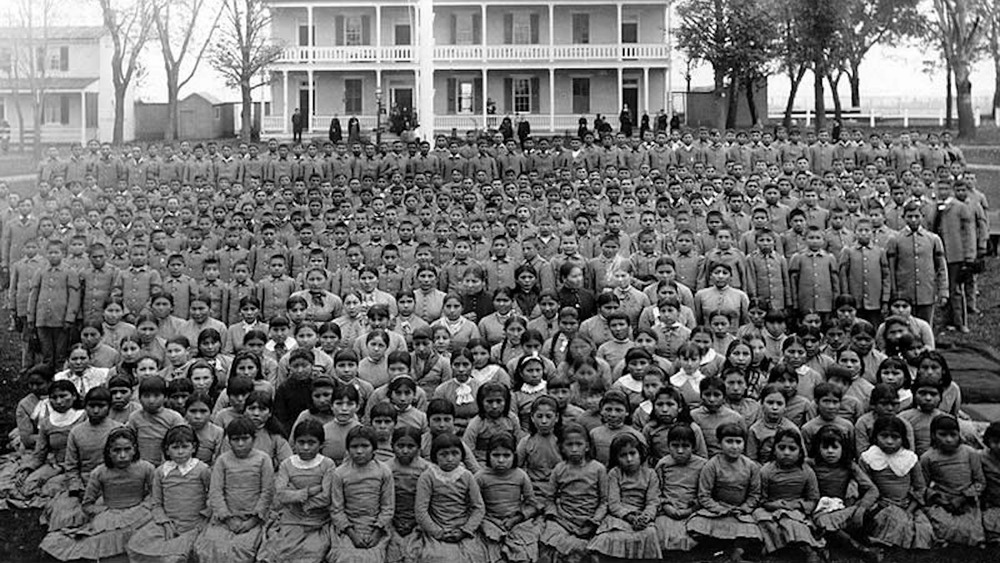

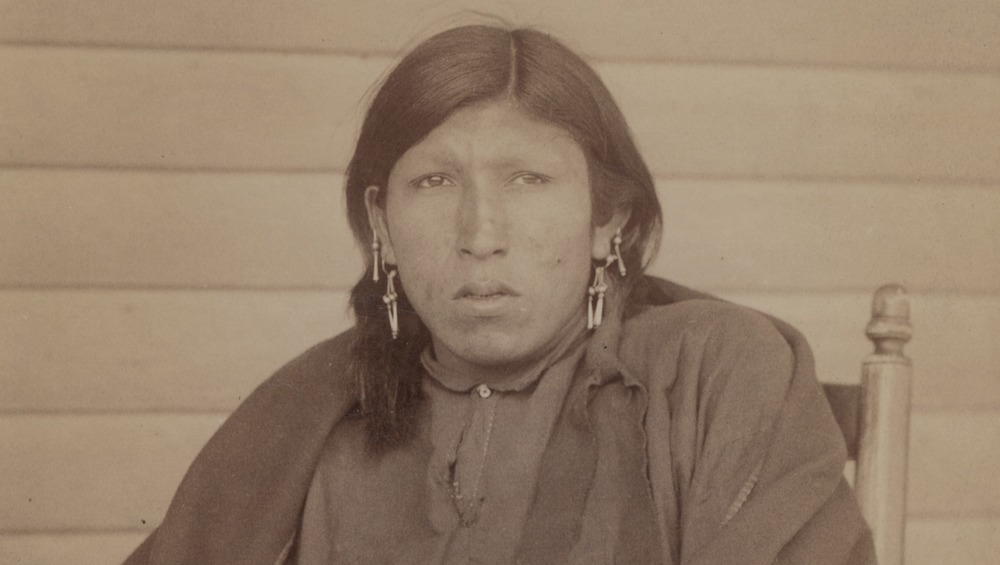

Photography as propaganda

Richard Henry Pratt used photography to demonstrate the success of his school and the degree of transformation that these Native children were undergoing. According to "Visualizing a Mission," all of Pratt's photos were heavily orchestrated "in order to heighten the contrast between their 'savage' and 'civilized' state and emphasize the efficacy of Pratt's educational methods."

John Nicholas Choate worked as the photographer of the Carlisle school from its opening until his death in 1902. Choate ended up creating hundreds of cabinet cards, boudoir cards, and stereographs featuring Indigenous children, selling the cards for at least $2 per dozen. Pratt also included the photographs in his correspondence, using them to win the support of reservation agents and state administrative officials.

Pratt himself recognized the use of these pictures as propaganda and mentions including them in his letters in his autobiography, "Battlefield and Classroom."

According to Indian Country Today, not every student was photographed. Over 8,000 children passed through Carlisle's door, and Pratt "just needed a few representative samples to use for [his] propaganda."

An incalculable amount of abuse

The conditions at almost all the off-reservation boarding schools were later found to be consistently horrendous. According to World Without Genocide, "at Carlisle alone, there were almost 200 children buried in the school's cemetery." Some of the children died as a result of physical abuse, while others succumbed to various outbreaks of diseases.

Anthony Galindo's grandparents were both educated at a boarding school, and he recalls his grandfather telling him how "they made [him] eat soap and then they beat [him] for speaking [his] language." Physical abuse was commonplace at many of the boarding schools, and children were often forced to do heavy labor. And even though corporal punishment had been banned by an 1895 federal policy, superintendents and agents were allowed to use it if they deemed it necessary.

According to WKAR, reports of sexual abuse were also widespread. In "Civilization and sexual abuse," Ewa Skał also writes that "some Native children were involuntarily sterilized."

The 1928 Merriam report eventually revealed that children at a majority of the boarding schools were poorly educated, harshly punished, and malnourished. However, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) "did not issue a policy of reporting sexual abuse until 1987 and did not issue a policy to strengthen the background checks of potential teachers until 1989."

Compulsory attendance

Many Native parents understandably refused to send their children to a place where they were being abused, starved, and isolated. According to "Chemawa Indian Boarding School," Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano responded to this by withholding annuities from those who refused.

Carl Schurz, his successor, went even further, and on March 1, 1889, was given the power by Congress "to make and enforce by proper means such rules and regulations as will secure the attendance of Indian children of suitable age and health." According to everyday feminism, in 1893, this mandatory education was reiterated as federal policy when Congress authorized BIA agents to withhold treaty-obligated rations if parents refused to send their child to a boarding school.

However, this didn't stop many parents and leaders from resisting the kidnapping and forced assimilation of their children. According to "Cheaper than Bullets," by Tabatha Toney Booth, "some agents even used reservation police to virtually kidnap youngsters, but experienced difficulties when the Native police officers would resign out of disgust, or when parents taught their kids a special 'hide and seek' game." And in 1895, 19 Hopi leaders were imprisoned at Alcatraz for refusing to allow their children to go to the Keams Canyon Boarding School.

Children also frequently ran away from the boarding schools.

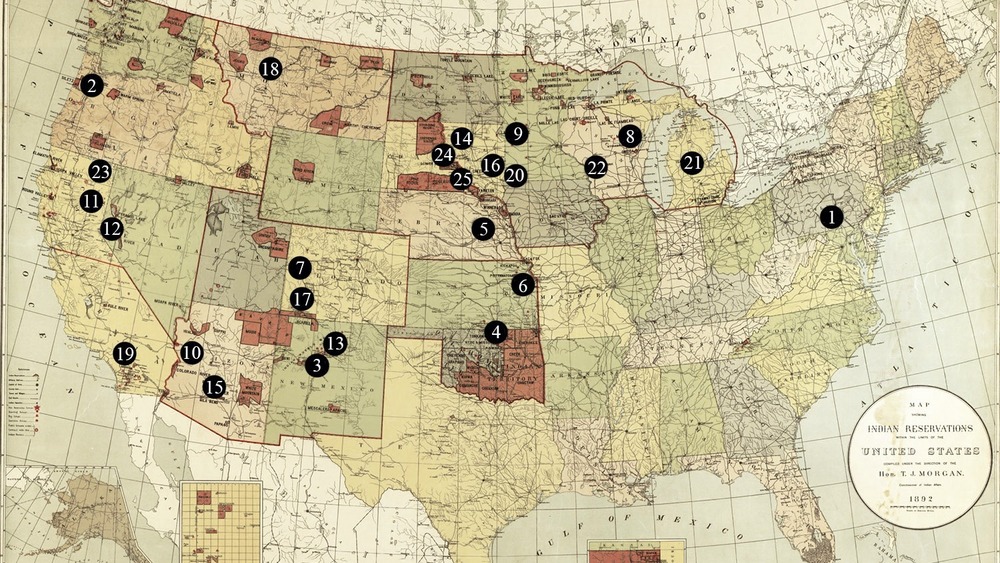

Boarding schools around the country

In total, there were 367 boarding schools across the U.S. According to the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center, 25 of those were entirely operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The majority of the schools were located in Oklahoma (83), Arizona (51), Alaska (33), New Mexico (26), and South Dakota (25). And even those that weren't under direct federal supervision "received subsidies from the federal government for their operations, typically based on the number of students." It's impossible to know exactly how many children went through the boarding school system, but it's estimated that between 1869 and the 1960s, "hundreds of thousands of Native American children were removed from their homes and families."

As of 2020, 73 schools are still open, 15 of which are still boarding schools. According to "Chemawa Indian Boarding School," the Chemawa Indian Boarding School, established in 1880, is "the oldest functioning off-reservation Indian boarding school in the United States."

Insurmountable loss

Since the government doesn't know how many children passed through the boarding schools, it's also unclear how many children died at the boarding schools. According to The Intercept, the number is estimated to be in the thousands.

Indian Country Today reports that many of the children died as a result of disease, while others died trying to escape. There was also at least one incident of a child dying in a boiler room explosion. And sometimes, rather than informing the family, the BIA agent assigned to the area was informed of the death instead of the family.

According to Indianz, the death rate at Carlisle was deliberately covered up. "Carlisle had higher death rates in the census years than almost every state that had an Indian nation. Carlisle had a higher death rate than war zones. During the Spanish American War a Carlisle student was more likely to die than a soldier going into war." It's estimated that at least 500 Native children died at Carlisle alone.

Sick children were sometimes sent back home so that they wouldn't make the school look bad. Tragically, the child often died while traveling or within a few days of arriving home, leaving families grieving while school statistics were "white-washed."

Those who survived

Many who survived the boarding schools remember them as painful and traumatic times. But for some, the experience was considered preferable to the alcoholism or hunger on the reservations. For those who went back to their homes, "their transition was not always an easy or pleasant one." According to "Chemawa Indian Boarding School," many who returned home had lost their native languages and sometimes found the differences overwhelming.

Some, like Zitkála-Šá (Gertrude Simmons Bonnin), found that when they returned to the reservation that they'd been changed by the boarding school and felt as though they no longer fit in at the reservation. Zitkála-Šá even ended up becoming one of the few Native teachers at Carlisle Indian School, but she left after less than two years because "the experience reminded her of her own traumatic education."

Instead, she turned to writing, publishing her own stories that shared her personal experiences at the boarding schools, as well as collections of Native legends. She also devoted herself to Native rights activism, working as a research agent for the Indian Welfare Committee, and co-authored the pamphlet "Oklahoma's Poor Rich Indians."

Others who survived and went on to fight for Native self-determination include Wassaja (Carlos Montezuma), Matȟó Nážiŋ (Óta Kté or Luther Standing Bear), and Ohíye S'a (Hakadah or Charles Alexander Eastman).

Nothing left to lose

Others felt themselves irrevocably changed by their ordeal and ended up going to great lengths to find themselves again. When Tasunka (Plenty Horses) returned home to the Rosebud Indian Reservation from the Carlisle Indian School, he realized that the education he received was practically useless.

According to "Our History Is the Future," by Nick Estes, Tasunka recalled how "there was no chance to get employment, nothing for me to do whereby I could earn my board and clothes, no opportunity to learn more and remain with the whites. It disheartened me and I went back to live as I had before going to school."

But upon returning to the reservation, Tasunka was only further disheartened. He saw his people starving and "killed with impunity at Wounded Knee." Later at his trial, Tasunka said, "When I returned to my people, I was an outcast among them. I was no longer an Indian. I was not a white man. I was lonely."

Nine days after the Wounded Knee Massacre, Tasunka shot Lt. Edward Casey in the back of the head. At his trial, he said he did it "so I might make a place for myself among my people. I am now one of them. I shall be hung, and then Indians will bury me as a warrior." However, Tasunka was acquitted of murder since the court decided that "a state of war existed, although not formally declared."

Revelations of the Merriam Report

In 1928, the Merriam Commission published the findings of their two-year investigation into the Indian boarding schools across the country. According to The Ziibiwing Center, the report found that children lacked basic things like beds, blankets, and toilet paper, and were overwhelmingly underfed. Many of the schools also suffered from overcrowding, and unsanitary conditions led to infectious diseases running rampant. Tuberculosis and trachoma were the two most common diseases amongst the boarding schools.

The Merriam Report also noted that "the question may very properly be raised as to whether much of the work of Indian children in boarding schools would not be prohibited in many states by the child labor laws."

However, none of the recommendations of the report involved closing the schools down. Instead, more money was appropriated for the schools, which did help remedy their conditions a little bit. But it wasn't until John Collier became commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1935 that boarding schools started closing.

Passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act

It wasn't until 1978, when the Indian Child Welfare Act passed, that Native parents were finally given the legal right to keep their child away from a boarding school.

The ICWA Law Center writes that this law was also in response to the fact that during the 1950s to 1970s, Indigenous children were being removed from their families and being placed into non-Native foster and adoptive homes at an alarming rate. The Association on American Indian Affairs reports that by the 1960s, almost 35% of all Native children in the U.S. had been separated from their families.

Despite the slow closure of boarding schools, in 1973, "there were still 60,000 Native children enrolled," according to Indian Country Today. And unfortunately, "statutes of limitations in the U.S. courts regarding lawsuits against individuals or institutions prohibit legal actions."

In recent years, the remaining boarding schools have changed their philosophy and are more concerned with "maintaining one's cultural identity." But for many, this doesn't come close to undoing the damage they caused.

Indigenous boarding schools around the world

The U.S. wasn't the only country with boarding schools specifically designed to forcefully assimilate Indigenous children. Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, Venezuela, Brazil, and Norway, among others, all had or currently have boarding schools for Indigenous children as well.

In many of these countries, the conditions of the boarding schools were incredibly similar to those in the U.S. In Victoria, Australia, "between 1881-1925, one third of indigenous children died." In Canada, it's thought that at least 3,000 children died in the mandatory boarding schools, writes the BBC.

According to "Indigenous Peoples and Boarding Schools: A comparative study," many countries with a history of Indigenous boarding school abuse have refused to address this legacy. While the Canadian government and the Australian government have both formally apologized for the history of boarding school abuses in their country, as of 2021, "the United States government has not yet acknowledged its role in operating American Indian Boarding Schools."

A federal investigation

In May 2022, the U.S. Department of the Interior released an investigative report into Native American residential schools. NBC reports that this is the very first time in the history of the United States that the government "attempted to comprehensively research and acknowledge the magnitude of the horrors it inflicted on Native American children." According to the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report, the U.S. government ran or supported over 400 federal Native boarding schools across the United States between 1819 and 1969. The investigation also found burial sites at 53 different schools, and "as the investigation continues, the Department expects the number of identified burial sites to increase."

The report confirms what many Indigenous communities in the United States have known for over a century: that the federal boarding schools were horrifically abusive and genocidal places that targeted Native children for forced assimilation and intended to "sever the cultural and economic connection" between Indigenous communities and their territories. The report also estimates that "the approximate number of Indian children who died at Federal Indian boarding schools to be in the thousands or tens of thousands."

The United States isn't the only place where mass graves of Indigenous children have been found associated with residential schools. Since May 2021, over 1,000 unmarked children's graves have been found in Canada. According to the Navajo-Hopi Observer, the discovery of the mass graves in Canada is what prompted the investigation in the U.S.