The True Story Of The 1968 Poor People's Campaign

The Poor People's Campaign was beset by national tragedies. It was preceded by the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and midway through, Robert Kennedy's assassination. But despite these devastating events, people from across the country gathered together in Washington, D.C. in 1968 to bring attention to poverty in the United States.

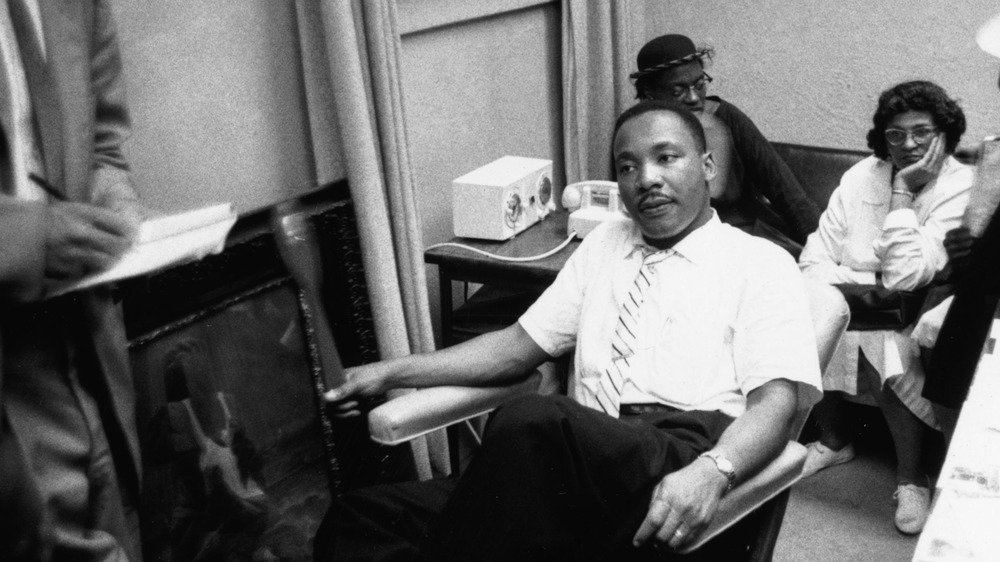

The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University reports that during one of the planning meetings for the Poor People's Campaign, Dr. King described it as "the beginning of a new co-operation, understanding, and a determination by poor people of all colors and backgrounds to assert and win their right to a decent life and respect for their culture and dignity."

Pushing for an "economic bill of rights," which underlined the right, among others, for everyone to have a "secure and efficient income," the Poor People's Campaign also focused on ending the U.S. imperialist intervention in Vietnam, according to Swarthmore College's Global Nonviolent Action Database. This is the true story of the 1968 Poor People's Campaign.

Organization of the Poor People's Campaign

The idea for the Poor People's Campaign was first put forward in November of 1976 by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. during a Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) staff retreat. However, according to The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute, the idea was first suggested to Dr. King by Marian Wright Edelman, who at the time was the director of the NAACP's Legal Defense and Education Fund in Jackson, Mississippi. In the mid-1960s Edelman had become the first Black woman admitted to the Mississippi Bar, per the Encyclopedia of African American Education.

In A New and Unsettling Force, posted at KairosCenter.org, Bertha Burres notes that Dr. King was focused on "recognizing the structural nature of poverty" as well as racism throughout his career. In his book In a Single Garment of Destiny, Dr. King wrote, "The dispossessed of this nation — the poor, both white and Negro — live in a cruelly unjust society. They must organize a revolution against that injustice, not against the lives of the persons who are their fellow citizens, but against the structures through which the society is refusing to take means which have been called for, and which are at hand, to lift the load of poverty."

The Poor People's Campaign was announced in December, 1967. According to Rediscovering Black History, the goal of the campaign was to bring attention to affordable housing shortages, unemployment, and the state of poverty in the United States "regardless of race."

Goals of the Poor People's Campaign

Many different communities, including the Puerto Rican, Native, and poor white, "pledged themselves to the Poor People's Campaign," per The King Institute. King himself wrote in "Notes on American Capitalism" in 1951 (also posted at The King Institute) that capitalism "has failed to meet the needs of the masses."

The campaign was also in response to President Lyndon B. Johnson's war on poverty, which "did little to encourage the political empowerment of the poor and made no attempt to critically examine the edifice that continued to produce poverty," Burres writes.

Although the SCLC thought that the Poor People's Campaign was "too ambitious" and without clearly defined plans, Dr. King recognized not only the importance of this campaign, but that the simplicity of their demands was essential. They planned for 3,000 people to travel to Washington, D.C. to "petition the government for an 'economic bill of rights'" during a non-violent demonstration on April 22, 1968.

According to the Global Nonviolent Action Database, their economic bill of rights featured five points, including the rights to a "meaningful job with a livable wage," "a secure and efficient income," the ability to "access land for economic reasons," and "access to capital to promote businesses" for "less well-off people." It also advocated giving "middle class" people a "large role in government."

Reaction of the U.S. government

The United States government freaked out before the actual demonstration even started. According to historian Gerald McKnight, quoted by The New People Newspaper, "the Johnson administration reacted as though the campaigners were an invading horde from a strange land intent on the violent disruption of the government rather than fellow Americans, most of whom were underprivileged and powerless nonwhite citizens." There were also worries in the administration that the demonstration could start a riot, based on the various uprisings and riots that had swept the county during the previous year in what KQED characterized as the "long, hot summer."

According to APM Reports, a memo from February 29, 1968 also suggests that President Johnson was interested in finding out whether or not Dr. King was a communist, due to the "massive civil disobedience campaign to be held in Washington, D.C. [...] to pressure congress into passing legislation favorable to the Negro."

One month before the demonstration was planned to occur, the FBI had already made a list of every organization that had endorsed the campaign. There were also plans to deploy at least 20,000 troops to "defend the Capital against the marchers."

Demonstrating after tragedy

Before the planned Poor People's Campaign, Dr. King went to Memphis, Tennessee to support the Memphis Sanitation Workers' Strike. Speaking at a rally for the workers on March 18, Dr. King said, "Our society must come to respect the sanitation worker. He is as significant as the physician, for if he doesn't do his job, disease is rampant," per Facing History.

According to APM Reports, the SCLC initially didn't want Dr. King to go to Memphis, since they were still trying to organize the upcoming Poor People's Campaign, but Dr. King was adamant. He returned to Memphis twice more, but tragically, during his second return there, he was assassinated, on April 4, 1968.

The King Institute writes that the SCLC decided not to cancel the campaign, delaying it instead by a few weeks. Then, on May 12, 1968, "thousands of women, led by Coretta Scott King, formed the first wave of demonstrators."

Resurrection City

On the second day of the demonstration, the protestors built a temporary settlement on the Mall in Washington, D.C., which became known as Resurrection City. Staying in the makeshift shacks and tents for six weeks, "demonstrators made daily pilgrimages to various federal agencies to protest and demand economic justice," per The King Institute.

According to The New People Newspaper, the population of Resurrection City "fluctuated between 1,500 and 3,000" during those six weeks. But on June 24, 1968, the Department of the Interior forced Resurrection City to close, using police to clear people out and bulldoze what was left. Apparently, their permit to use the park had expired and despite applying for a 30-day extension they'd only been given a week, Burres writes. It also likely wasn't a coincidence that previously, on June 19, there had been a rally that "drew over 50,000 participants."

Although the Poor People's Campaign didn't lead to an "economic bill of rights," it had its successes. According to the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture, 1,000 of the neediest counties in the country received food programs, labor programs were extended by Congress, and "the government also approved rent subsidies and home ownership assistance for the poor."