The Inventor Of Motion Pictures Vanished And The Case Remains Unsolved

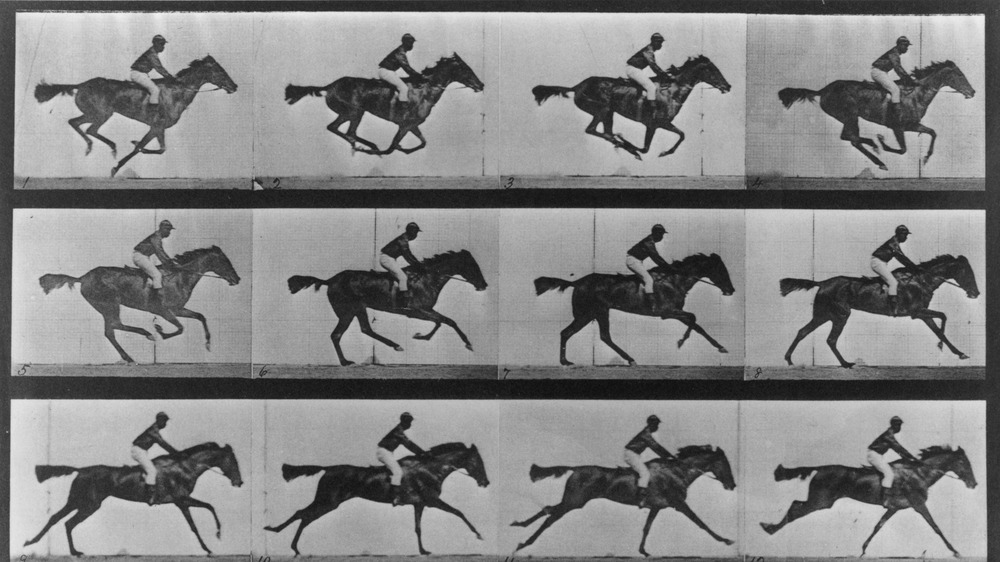

Who wears the mantle as inventor of the motion picture? Some might say English photographer Eadweard Muybridge, who, reports The Atlantic, sought to answer the question of whether all four of a horse's legs were ever off the ground at the same time as it ran. He took 12 photos of a running horse and proved that all four hooves lifted from the ground. He then created a photo projector in 1879 that showed his photos in a sequence that demonstrated movement.

Or maybe French physiologist Etienne-Jules Marey should wear the title. His research looked at the way animals moved and to facilitate his study he developed a camera with the ability to capture 12 photos each second, writes Better Photography.

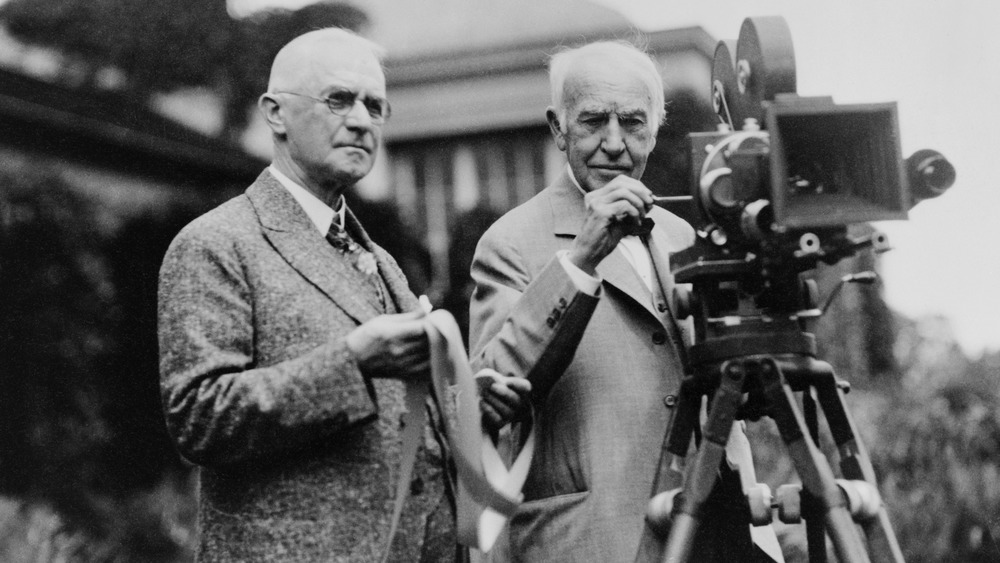

Could it be the American inventor Thomas Edison, working with his assistant William Dickson, who in 1891 (per Britannica) released the Kinetograph — a simple motion picture camera — and in 1892, the Kinestoscope, a projection machine? Or perhaps the French Lumiére brothers, whose 1895 Cinématographe, as History.com tells us, acted as a recorder, developer and projector?

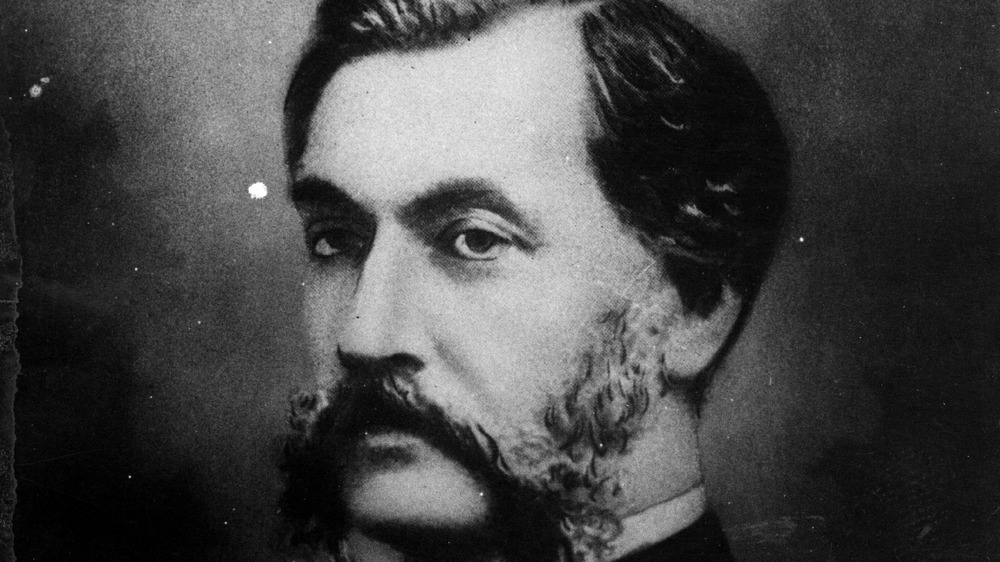

In truth, all had a part in the invention's evolution. But yet another individual should also receive credit: French artist Louis Le Prince, who, according to Buzzfeed, worked on similar experiments until his mysterious disappearance in 1890.

From galloping horses to films of traffic

Le Prince's interest in images started early. The innovator Jacques Louis Daguerre, creator of the daguerreotype photograph process, was a family friend, and the boy frequented his studio. In 1869, Le Prince founded the School of Applied Art with his wife, Elizabeth. That year, he saw Muybridge's sequential photos of a horse in motion and became intrigued with the science of moving pictures.

By 1886, he had invented and patented in America a 16-lens camera that could take 16 photos a second, creating a series of still images with the intent of making a motion picture. He later would work with a single-lens version. An 1888 British patent for his invention included an "extra clause" about it, according to the National Media Museum in England.

He continued experimenting until he had developed a project he could show to the public, including films he shot on Leeds Bridge and at his wife's family home in Roundhay. (Watch his film of traffic moving over Leeds Bridge on YouTube.) According to the BBC, his wife "prepared a theatre for the unveiling of his films to the world in their New York mansion."

She had traveled ahead of Le Prince, who stayed behind to finish some family business. On September 16, 1890, the would-be inventor of motion pictures waved farewell to his brother Albert at the Dijon station, headed for Paris. He never was seen again.

A court battle decides the inventor of motion pictures

Conspiracy theories on what exactly happened to him include his wife's claim that Edison played a part — after all, it benefited Edison to have a competitor removed. Other hypotheses, according to BuzzFeed, say that Albert caused his demise, or that Le Prince deliberately disappeared, hoping to avoid debts. To this day, no one knows exactly what happened to him.

Edison would contest his discovery seven years later in patent court, and eventually Le Prince's work was invalidated, with Edison ultimately getting credit for pioneering the technology for motion pictures. Some historians still talk about Le Prince's impact. Writing in Screen, Richard Howells purports that "Le Prince had indeed succeeded making pictures move at least seven years before the Lumiére brothers and Edison."

If you're curious about solving the mystery yourself, visit the National Science and Media Museum in England, which currently houses Le Prince's camera and footage. "If you look at the mechanism that camera is using, it's a very similar mechanism to all the subsequent moving image cameras that came after that," Toni Booth, associate curator at the National Media Museum in Bradford, England, told the BBC. " ... As a piece of moving image recording live action — yes I would say he was the first one to do that."

Hmmm ... what do you think?