The True Story Of How New York City Displaced A Black Community To Build Central Park

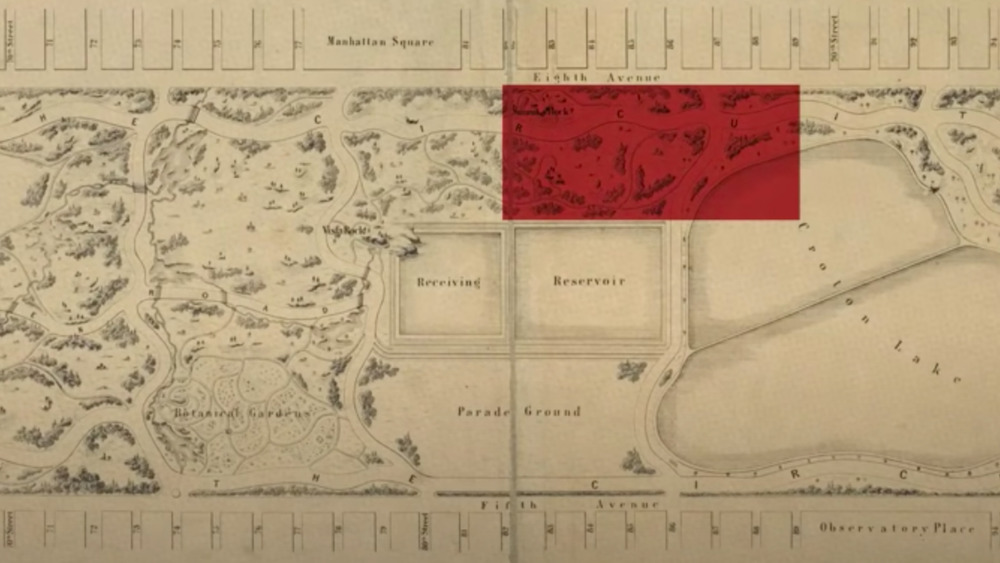

Before Central Park was landscaped into the island of Manhattan, the area was home to many different residential settlements ... that the city of New York evicted in order to build their sprawling luxurious park. One of these residential settlements, known as Seneca Village, was not only one of the few majority-Black neighborhoods but it was one of the few places in New York City where Black people owned their own property.

Although Seneca Village was effectively wiped from the face of New York City in 1857, an archeological excavation in 2011 began to uncover a thriving multi-ethnic middle-class community that became one of the first victims of gentrification.

Seneca Village only survived for 32 years, but during that time it was a "tight-knit community that served as a stabilizing and empowering force in uncertain times." And researchers are still looking for more information about Seneca Village and its residents and anyone with information is encouraged to reach out to the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History. This is the true story of how New York City displaced a Black community to build Central Park.

The founding of Seneca Village

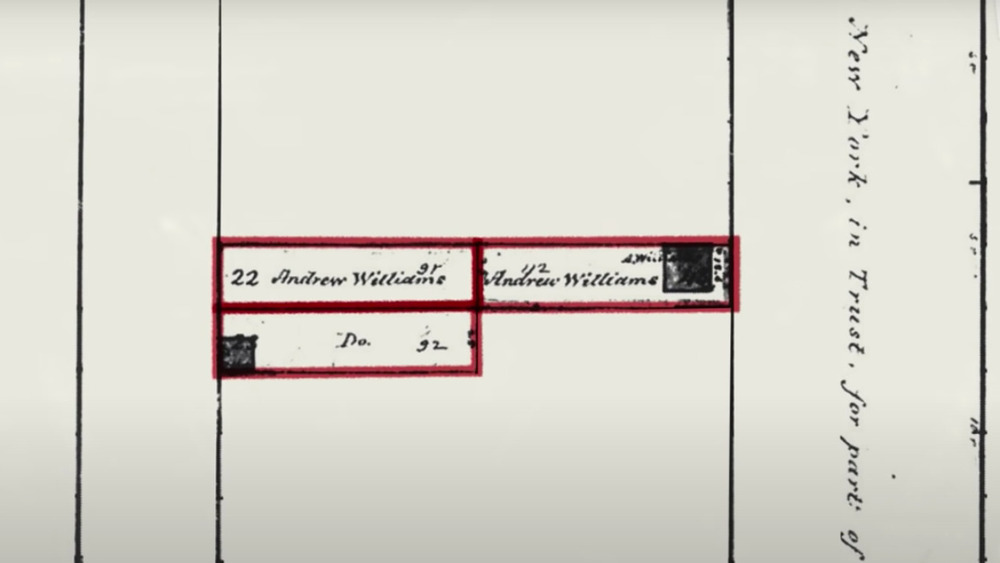

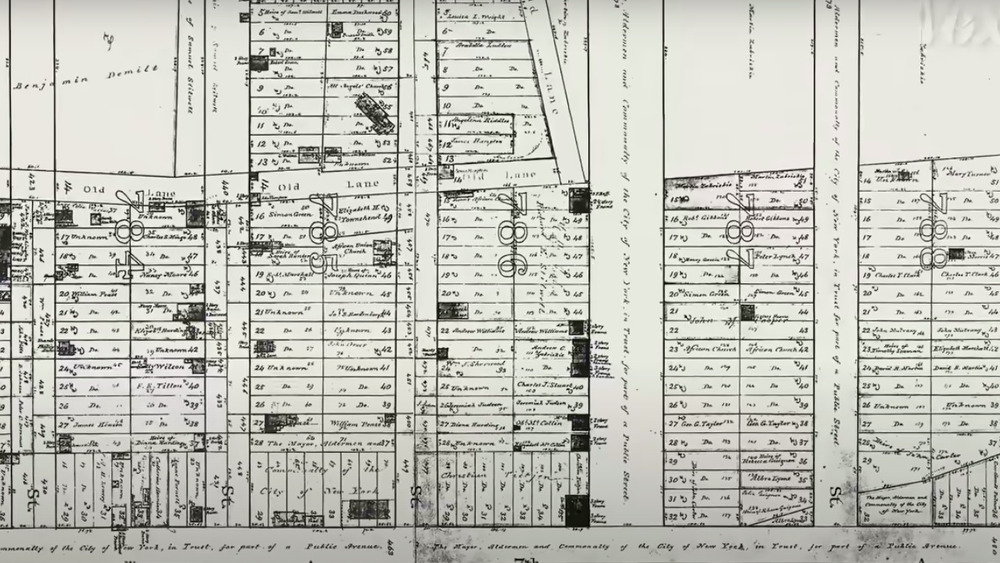

Many credit Andrew Williams, a member of the The New York African Society for Mutual Relief, with the creation of Seneca Village, because he was the first one to purchase some land in the area. According to the New York Historical Society, Williams bought three lots of land on September 27th, 1825 from Elizabeth and John Whitehead. One lot was on the south side of 86th Street, while the other two were on the north side of 85th, between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. Interesting Sh*t writes that Williams paid $125 for all three lots together, and that the Whiteheads, unlike many white landowners in the region, were some of the few who would sell property to Black Americans. According to Central Park Conservancy, "from 1825 to 1832, the Whiteheads sold about half of their land parcels to other African Americans."

Within one week the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church also purchased "six lots of neighboring land" and Epiphany Davis, a church trustee and member of the African Society, purchased 12 more for $578. And by 1832, according to MAAP, Black Americans purchased at least "25 more lots" in the area.

During the first few years, nine homes were built in what would become known as Seneca Village. And within 25 years, the community "boasted three churches, a school, and a population of some 300 people."

New York gradually ends slavery

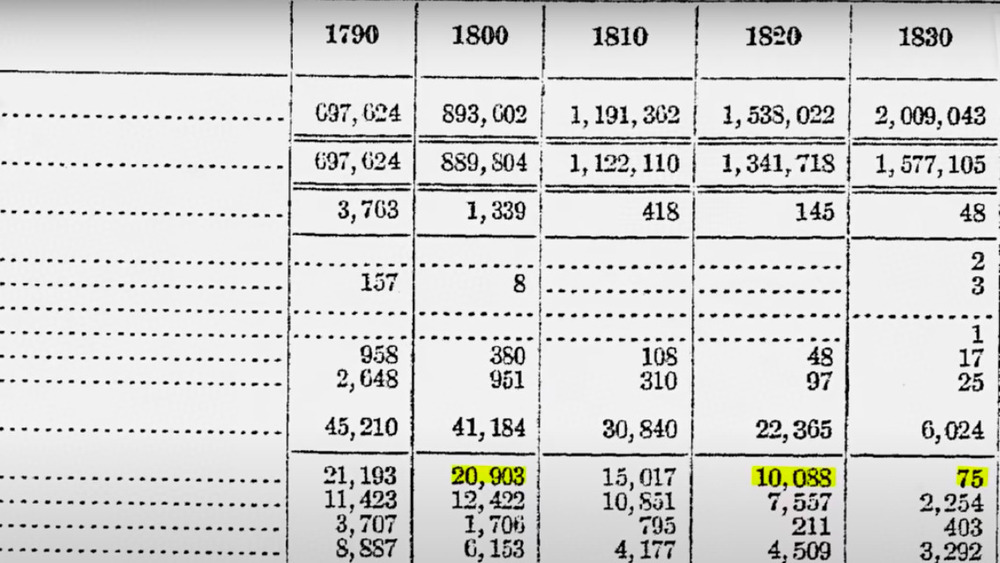

The State of New York gradually banned enslavement, but it took almost 50 years for the majority of enslaved people in New York to be freed. According to the New York Historical Society, the first Gradual Emancipation Act was passed in 1799, which stated that children born to an enslaved mother after July 4th, 1799 were freed, but only once they were in their 20s. Until then, they were to remain in bondage.

CUNY Academic Commons writes that another law was passed in 1817, which was meant to "emancipate the enslaved people from before the enactment of the law in 1799." But census records show that from 1810 to 1820, the number of enslaved people in New York State only went from 15,017 to 10,088. However, by 1830, the number had decreased to 75, was down to four by 1840, and only by 1850 is the number considered to be zero, showing an incredibly gradual decline.

According to Central Park Conservancy, despite this gradual abolition, there was still a great deal of discrimination from the white people living in the City. Seneca Village was especially appealing for this reason, since it was relatively remote from downtown Manhattan and "provided a refuge from this climate. It also would have provided an escape from the unhealthy and crowded conditions of the City, and access to more space both inside and outside the home."

The largest concentration of Black property owners

Since most white landowners refused to sell lots to Black people, Seneca Village became one of the few places in New York City where Black people could own property. And according to Interesting Sh*t, since New York State ruled in 1821 that in order to vote, Black men had to "own at least $250 in property, something not required of white voters," being able to buy property in Seneca Village also meant being able to acquire voting rights.

According to Longreads, despite the fact that by 1820, there were almost 11,000 free Black people living in New York City, "by 1826, only 16 Black men in the city were able to cast a ballot." Central Park Conservatory writes that by 1845, there were 100 Black men in New York City who were eligible to vote, 10 of whom lived in Seneca Village. According to The Park and The People by Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar, there were even some Black landowners in Seneca Village, like Joseph Marshall, who also owned a house in lower Manhattan.

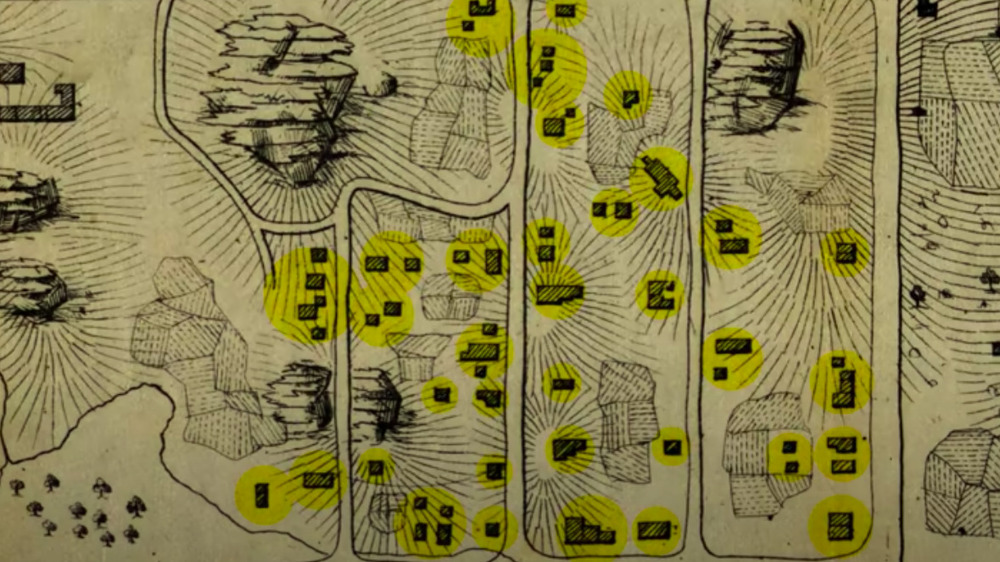

It's estimated that roughly half of the Black residents of Seneca Village owned their land, "a number that was five times the national average for the entire city." They were also "39 times as likely to own property as other black New Yorkers." By the 1850s, Seneca Village had grown to encompass the area from 82nd to 89th Street, between 7th and 8th Avenue.

Inclusion of Irish and German immigrants

By the mid-1850s, the village was "a fully integrated community." Timeline writes that as lower Manhattan was becoming more and more crowded, and the Irish Potato Famine started in 1845, immigrant families also started moving into Seneca Village. Out of roughly 225 residents in 1855, up to one-third were Irish immigrants, and there was also "a small number of individuals of German descent," according to Central Park Conservancy.

Residents of the community shared various resources, such as the All Angels' Episcopal church as well as the All Angels' cemetery. There was also an Irish woman who was the local midwife for everyone in the community.

According to The Park and the People, compared to the Black residents of Seneca Village, only "three of 21 [Irish households] owned property, and none of the recent Irish arrivals did." And in the Encyclopedia of African American Society, Gerald D. Jaynes notes that "in a city noted for ethnic tensions and violence, Seneca Village stood out for its generally good race relations." There's also some evidence that people of Native descent may have also lived in Seneca Village, or in one of the surrounding residential settlements.

A village remote from the dense downtown

At the time when Seneca Village started flourishing, the bottom of the island of Manhattan was already a densely populated grid. According to the Seneca Village Project, New York City was called the "city of contrasts," since downtown New York was seemingly filled to the brim with people and buildings while uptown was uncultivated and expansive, with "hills, trees, rocking outcroppings, streams, and springs."

Central Park Conservancy writes that even though people in downtown Manhattan claimed that those living in Seneca Village were simply "poor squatters living in shanties," many of the residents in fact lived in two-story homes. In Prince of Darkness, Shame White writes that "Seneca Village flourished in the larger context of the city's uninhabited expansion."

And Seneca Village wasn't the only residential settlement in the surrounding area. There was also the Piggery District, Harsenville, and the Convent of the Sisters of Charity. All of these residential settlements had some combination of orchards, schools, shops, hospitals, cemeteries, churches, "and other institutions" across thousands of plots of land. And although children weren't required to go to school, according to Timeline, more than 75 percent of the children in Seneca Village attended school at Manhattan's Colored School No. 3.

A spot on the underground railroad

There's also evidence to suggest that Seneca Village was a spot on the Underground Railroad, the network of secret routes that helped Black people escape enslavement, helping them reach the North or go all the way to Canada. All That's Interesting writes that several of the basements in the village were used to hide Black people who were trying to escape enslavement.

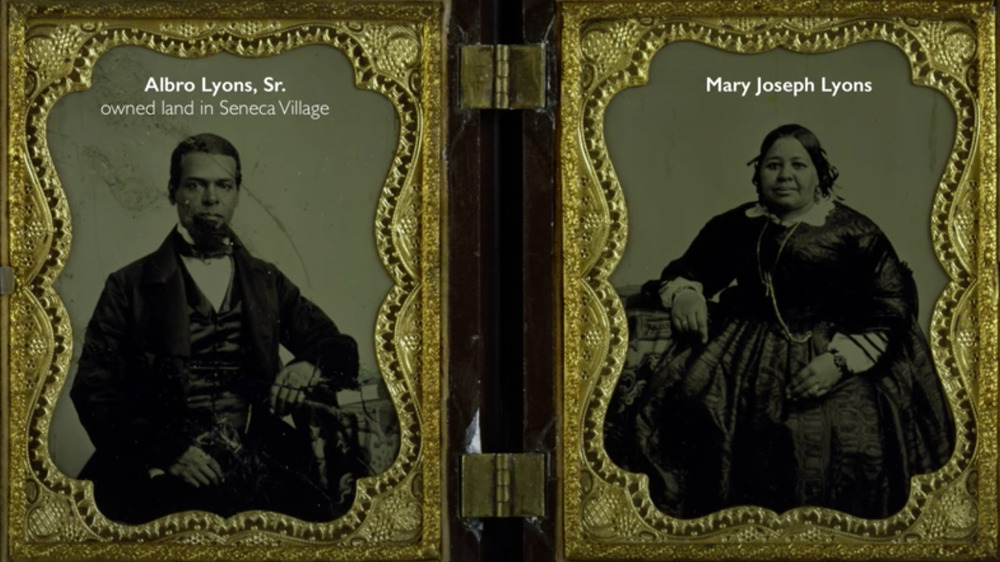

According to Timeline, Albro and Mary Joseph Lyons, prominent abolitionists who are now recognized as being part of the Railroad, or as "conductors," owned land and lived in Seneca Village. Running an outfitting store and a seamen's home, "their businesses served as a cover for their involvement in the Underground Railroad," Three Village Historical Society writes.

Apparently, it was rumored that even The New York African Society for Mutual Relief, whose members essentially founded the village, had a hidden basement that they used to hide people who'd run away from enslavement. It's also been suggested that the name of the village comes from the philosophical tract Morals by Seneca, which was "popular with abolitionist activists," although there's nothing to confirm this theory.

White elites call for a city park

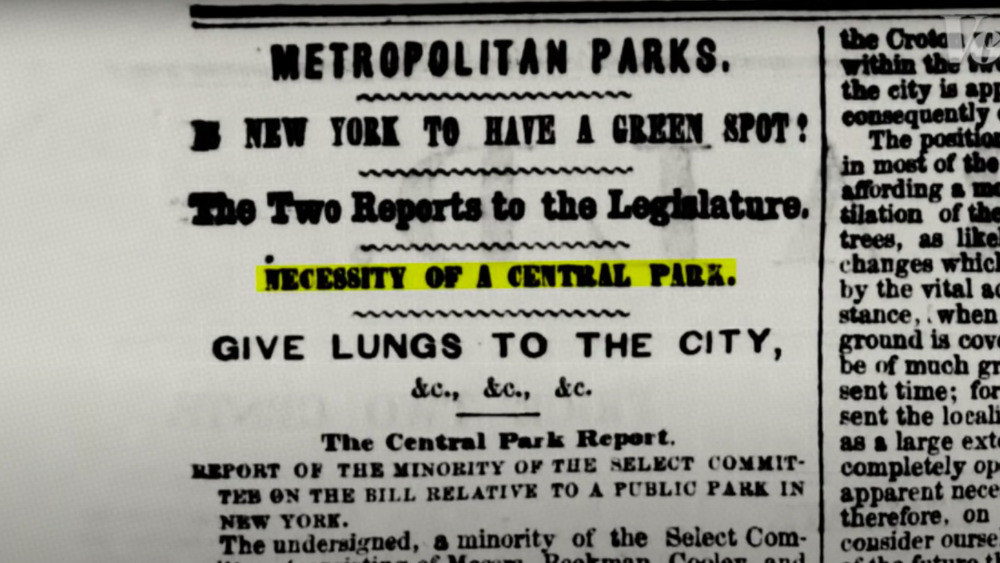

So why did so many thriving communities get replaced by a park? Vox reports that since the population of New York City was growing at an increasingly fast pace, and with lower Manhattan becoming more and more crowded, "the city's white elite were worried that the entire island would become consumed by development." By the 1840s, Timeline reports that some wealthy New Yorkers had already started moving uptown. At the time that the park was proposed, the "Lennox family and other wealthy New York names owned swaths of land in the vicinity of the proposed park."

As a result, the rich white people of New York said that a city park was "necessary" in order to "give lungs to the city." This demand was partly inspired by the fact that the elite were able to travel to Europe, seeing Kensington Park and the Champs-Élysées, they decided New York City also "deserve[d] to have a park of that stature," according to public historian Cynthia Copeland.

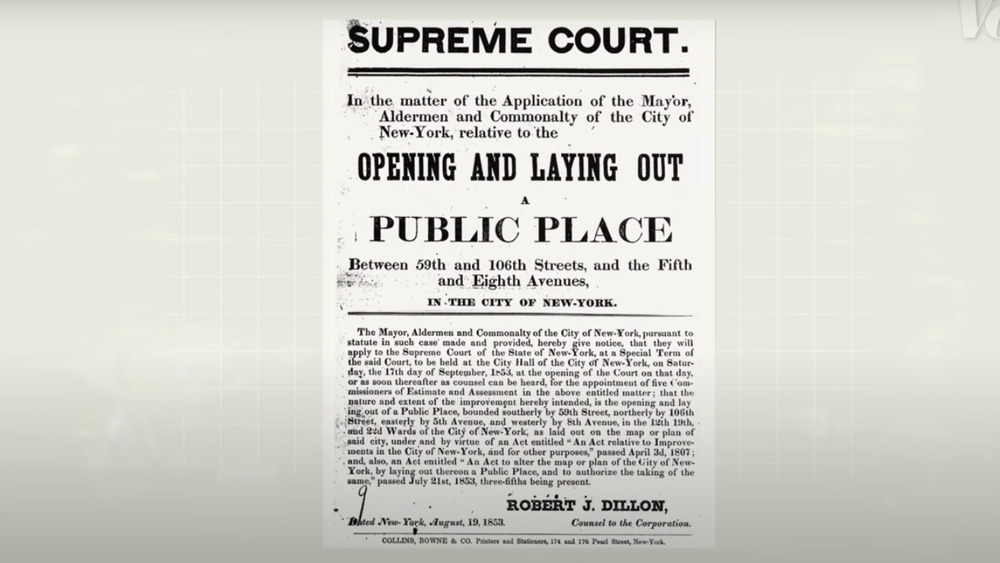

And on July 21st, 1853, New York City decided to allocate 750-775 acres of land to create the first major landscaped public park in the United States. Central Park Conservancy writes that the city was able to take the land "through eminent domain, the law that allows the government to take private land for public use with compensation paid to the landowner," which was also how the street grid of lower Manhattan had been built.

The city turns its gaze to Seneca Village

The first time that Mayor Fernando Wood sent police to Seneca Village for the new park was in 1855. However, according to MAAP, the residents of the village refused to leave and for two years they "resisted the police as they petitioned the courts to save their homes, churches, and schools." Timeline reports that even as a new church was being built and painted on 86th street, residents of Seneca Village were fighting for their homes in court.

Vox reports that in order to get the public on the side of eviction and development, newspapers like The New York Herald "downplay[ed] who really lived there." Residents and property owners who lived on the land that was meant to be developed were now being called "squatters" and were being described as "wretched and debased."

Rather than describing the thriving villages as they really were, Seneca Village was instead represented as "miserable looking broken-down shanties" that were barely standing in swampy conditions. Called "Squatters Village" by the papers, it was described "as if it were Darkest Africa." In this way, the city of New York cast Seneca Village and its surrounding neighborhoods as lands that were better off being a park and its residents better off dispersed.

The 1857 eviction

Unfortunately, by 1857, the city succeeded in evicting the roughly 1,600 people who lived throughout the area, including those in Seneca Village, that was to be made into Central Park. And although some residents were paid for their land, "many argued that the compensation was insufficient," according to Untapped Cities. Andrew Williams, who bought one of the original lots, was paid almost what his land was worth, but only "after filing an affidavit with the state Supreme Court." Epiphany Davis wasn't so lucky, and lost "hundreds of dollars," Timeline writes.

And according to All That's Interesting, despite these isolated cases, most of the residents for Seneca Village received nothing for their land. And with one fell swoop, thousands of homes were erased from existence, leaving Central Park behind in its stead.

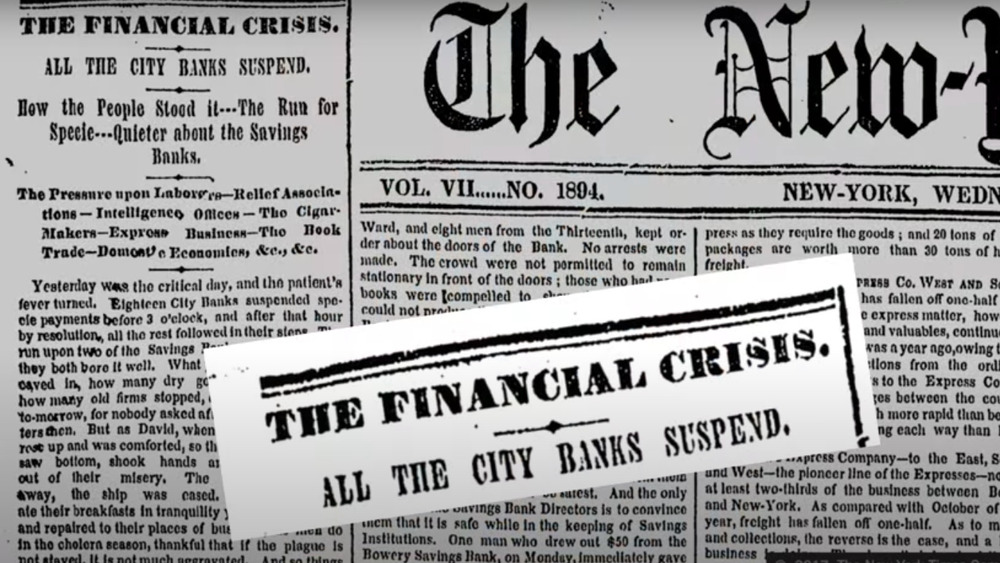

In a local newspaper, it was said that the eviction of Seneca Village would "not be forgotten...[as] many a brilliant and stirring fight was had during the campaign. But the supremacy of the law was upheld by the policeman's bludgeons." At the time, New York City was also struck by the Financial Panic of 1857, and it was an incredibly difficult time for anyone to lose their home and be forced to start over.

The 2011 excavation

Seneca Village was mostly forgotten about until the early 2000s, when researchers started excavating the site where Seneca Village used to be. They started digging around in 2004, and in 2011, the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History began an archeological excavation of the area. According to Untapped Cities, they found various artifacts such as a roasting pan, a stoneware beer bottle, and an iron tea kettle.

The NYC Archeological Repository also notes that many of the objects found indicated that the people who lived there "saw themselves as members of the middle class, from the sturdy house itself to the household dishes and personal objects the family used." And according to Vox, there were also several porcelain pieces found in the archeological excavation of Seneca Village, "and porcelain was an expensive ware."

Part of a toothbrush was also discovered, which is incredibly significant because toothbrushes only became common in both the middle class and the working class around 1920. As a result, these discoveries stand in direct opposition to the claims levied against Seneca Village in the 1850s. Instead, Seneca Village is now finally being remembered for the "vibrant, middle-class, [and] multi-ethnic settlement" that it was.

The unknowns surrounding Seneca Village

Unfortunately, despite these recent discoveries, there's still little known about Seneca Village, and it seems that the city of New York was tragically effective at scattering its population. According to NPR, one of the biggest questions about Seneca Village is where its former residents moved to after the city evicted them: "Researchers have not been able to find a single living descendant of anyone who was a resident of Seneca Village."

Anthropologists have repeatedly made queries about the former residents and their descendants, and during an exhibit at the 1997 New York Historical Society, "the names of Seneca Village residents were listed and visitors were asked if they or anyone they knew were related to those original denizens." According to Central Park Conservancy, some researchers believe that the former residents may have moved to similar majority-Black communities in the area, like Sandy Ground in Staten Island or Skunk Hollow in New Jersey, but as of yet no one has come forward with information about the Seneca Village residents.

And so far, the excavation has only turned up fragments. Timeline writes that "the only official artifact that remains intact on the site is a commemorative plaque, dedicated in 2001 to the lost village."

Seneca Village repeats itself over and over again

The eviction of Seneca Village was one of the first acts of gentrification in the United States and unfortunately, it wasn't the last. High Country News reports that in 1962, the Portland Development Commission decided that the neighborhood of Albina, Oregon was a "worthless slum" and "proposed clearance to prevent the spread of slums to adjacent neighborhoods." They partnered with Emanuel Hospital, which was going to use the area to add 19 acres to its campus instead.

Homeowners were given "a flat $15,000 for their homes, far below market value," renters were given "a mere pittance," and everyone was told that they had 90 days to leave. Almost 300 Black residences were bulldozed. And then in the worst twist of fate, funding for the hospital fell through and as of 2018, many of those lots remain vacant almost 50 years later. So what was the point of pushing hundreds of Black people out of their homes?

In Atlanta, Georgia, Al Jazeera reports that another way of displacing Black communities is by promoting development in the surrounding area, causing an increase in home values. This ends up "pushing out low-income renters who cannot afford the jump in rent and homeowners who cannot afford the increased property taxes." According to NCRC, this phenomena is seen in hundreds of neighborhoods, and between 2000 and 2013, 135,000 residents were forced to move out of 230 neighborhoods due to "rapidly rising rents, property values, and taxes."