The Assassination Of This Canadian Commune Leader Is Still Unsolved After 100 Years

Any time people suffer a strange death that occurred under mysterious circumstances, theories are going to run rampant. A very similar sort of fascination comes out of strangely unique and insular communities that seem to exist on the fringes of mainstream society. There's just something about it that the human mind seems to enjoy, and a lot of the best stories are surrounded by at least a couple of crazy theories.

Well, how about one with at least seven viable theories, ranging from government cover-ups to possible patricide to the KKK? Because that's the case when it comes to Peter Verigin, the spiritual leader of the Doukhobor community in Canada. (Yes, Canada. And the KKK. It's not a typo.) Nearly 100 years have passed since he died, and his death (or, possibly, murder) still raises questions. Verigin made a lot of enemies in his time, so the speculation is, fittingly, quite the wild ride.

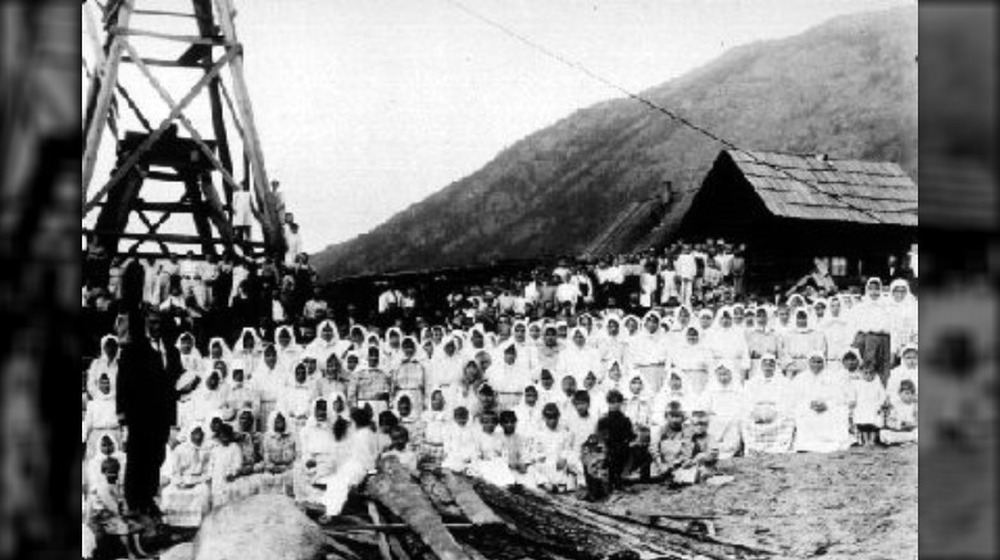

Who were the Doukhobors?

The origins of the Doukhobors are hazy at best. Their place of origin isn't exactly known (aside from, generally, somewhere in Russia), and when they formed can be narrowed down to sometime in the 18th century, according to USCC Doukhobors, which lines up with the tsar catching word of them in the 1750s (via Dictionary of Canadian Biography). Maybe the lack of information can be chalked up to their dependence on oral teachings: The records just aren't there.

Luckily, there's a lot more about why they were formed and what they believe in. At their core, the Doukhobors are a sect of Christianity, started mainly by Russian peasants who weren't pleased by the opulence they saw in the Orthodox Church. They thought that religion should be something simpler, something that didn't require complex rituals. Instead, they believed that there was a bit of God within each person, so looking for God just meant looking inward.

Of course, the Orthodox Church wasn't a fan, calling them "Doukhobors" ("spirit wrestlers") as an insult. But they adopted the name, adjusting its meaning: They weren't wrestling against spirits but instead for the spirit of God inside everyone. The problem was, their beliefs led to them ignoring leaders aside from their own, the tsar included. So when they started practicing pacifism, they weren't looked upon kindly, and thousands of Doukhobors were exiled into the Caucasus.

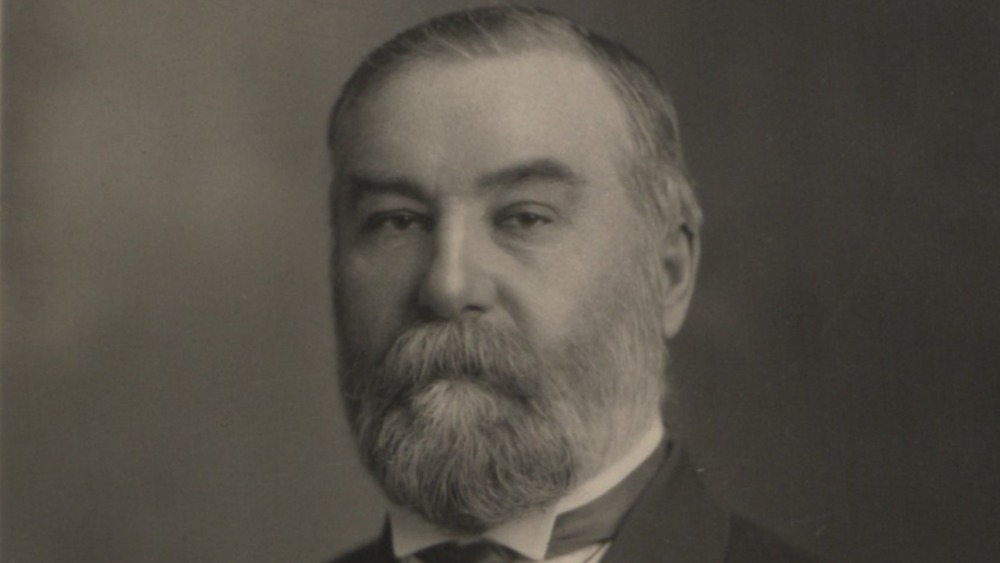

Peter Verigin and the Doukhobors

Born in the Caucasus on July 11, 1859, to a well-off family, Peter Verigin was actually the great-grandson of another Doukhobor leader, Savelii Kapustin, who headed the community in Southern Ukraine during the early 19th century (via Dictionary of Canadian Biography). Given a good education at an early age, Verigin was described as quick and intellectual, on top of being charismatic, which is probably what got him noticed by the higher-ups in the Doukhobor community.

Namely, it was the widow of his cousin — Luker'ia Vasil'evna Kalmykova, the leader of the Doukhobors — who took notice of Verigin in the 1880s, seeing that he was destined for "holy work" and forcing him into working for her (to the tune of divorcing his pregnant wife). But the change ended up working out well for him. Sort of. By the time Kalmykova died in 1886, Verigin was one of the main names being considered for leadership: He was actually enough of a threat that his opponents saw to it that he was arrested in early 1887 and sent into exile.

But, again, the unfavorable circumstances ended up working out. During his 15-year exile in the northern parts of Russia, Verigin ended up meeting with exiled revolutionaries and anarchists, and the experience overall brought his beliefs into sharper focus. Pacifism, vegetarianism, abstaining from violence and sin in general — his thoughts all made it into a manifesto which he sent to his followers.

Peter Verigin and the Doukhobors emigrated to Canada

The Doukhobors didn't exactly have a lot of friends within Russia, but they were starting to garner some notice from groups like the English Quakers (via Dictionary of Canadian Biography). And that's aside from Verigin having made the acquaintance of the famous writer Leo Tolstoy. Those connections ended up helping the Doukhobors find a new home in Canada, a move that was approved by the tsar in 1898, according to Library and Archives Canada.

Initially, Peter Verigin disagreed with the move on principle, but he ended up giving in, seeing it as their only real option to escape persecution. So he joined the four colonies, all established in the area that would later become Saskatchewan, once he was allowed to leave Russia in 1902.

But Canada wouldn't be the perfect solution, either. The Doukhobors practiced communal living, and legalities surrounding land ownership brought them into conflict with the government. The Minister of the Interior wanted individual registration of homesteads, which would imply obligatory military service, which the Doukhobors didn't want. Things got bad enough that the government actually took back about half the Doukhobors' land while Verigin took a trip back to Russia, and it was clear they needed a new solution.

That answer would come in mid-1907, in the form of orchard lands available for purchase in British Columbia. Many of the Doukhobors followed Verigin to these new lands, where they set up a quaint colony and thrived.

Peter Verigin was a pragmatic leader

Given the often-precarious legal situations that the Doukhobors usually found themselves in, Peter Verigin proved himself an exceptionally good leader, managing to maintain his status as a spiritual figure — they didn't call him "Gospodnii," meaning "Godly" or "belonging to the Lord" (via Dictionary of Canadian Biography), for nothing — while balancing the realities of the world around them.

Verigin was especially pragmatic. After all, the Doukhobors were, in effect, pacifist farmers who lived in a fairly insular community. That's a pretty far cry from rapidly industrializing countries, which tended to plunge themselves into war over any matter of dispute. The Doukhobors didn't really fit into that world, but Verigin understood when he should compromise for the good of his people.

He did try to find some sort of middle ground with the Canadian government over issues of land ownership in Sasketchewan. Part of his plan to keep their colony afloat was to have the men find jobs outside of their community, because they would realistically need the funds to pay for necessities. Verigin made an agreement that their children would attend public schools, so long as those schools stayed away from military or religious instruction, and he welcomed new technological advancements that helped the Doukhobors in their agricultural endeavors. All of it was compromise for the greater good.

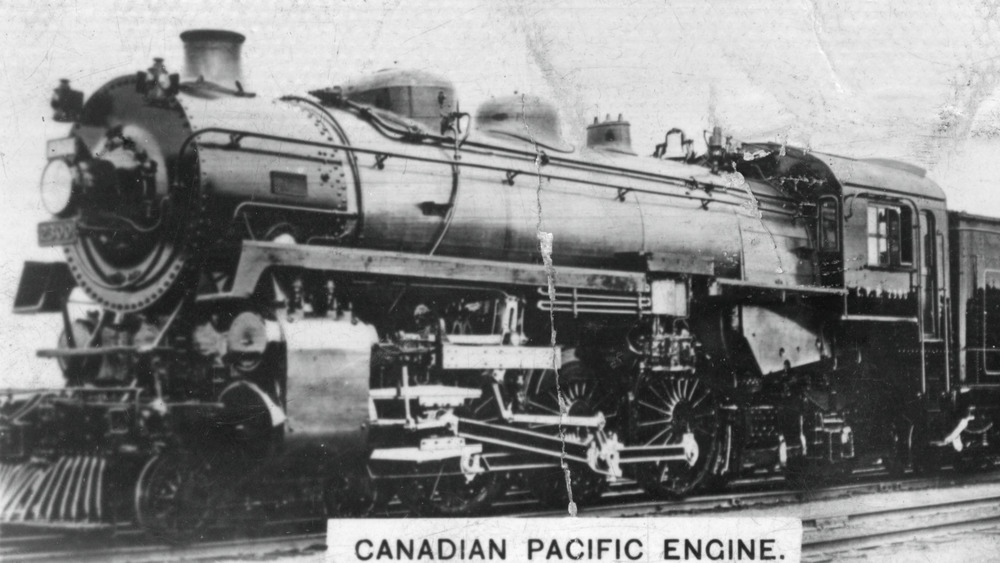

Peter Verigin met a gruesome end

Of course, there has to be a strange and mysterious part of this story, and that came in 1924, when Peter Verigin boarded a Canadian Pacific Railway train late in the evening on October 28 at a station in Brilliant, British Columbia. The Doukhobor Genealogy Website says that he was on his way to Grand Forks, accompanied by 20-year-old Mary Strelaeff, Grand Forks MLA John McKie, and a few other Doukhobors.

But they wouldn't make it to their destination. At around 1:00 a.m., near a small station in Farron, an explosion shattered the quiet night. Centered somewhere around Verigin's seat, the blast destroyed the train car, blowing off its roof and sides and blasting more than half of the occupants completely clear of the car.

With Farron being a pretty small station deep in the mountains and far from major roads, it would've been hard for authorities to arrive (via Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History), but they would've come upon a gruesome scene. Of the 21 people in the car, only two were left uninjured, with Verigin, McKie, Strelaeff, and six others dying in the blast. Verigin himself was found 15 meters from the car, one of his legs blown completely off.

The cause of the explosion was unknown, and, naturally, theories began to emerge.

An unfortunate accident?

It's not especially interesting, but one theory is that the explosion that killed Peter Verigin was a complete accident. At the scene, reports initially said that the blast was caused by a leaky gas tank. After all, gasoline was used to heat and light the train cars, and the tanks were situated directly underneath them, as Simyon F. Markhortoff was told on that night. The Canadian Pacific Railway denied that (via the Doukhobor Genealogy Website), but more interestingly, Markhotoff noticed that the car's gas tank and pipes were still completely intact. They couldn't have exploded.

So that pointed to a different kind of accident. The Nelson Daily News (via Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History) explains that, in that particular area, it wouldn't have been unsurprising for passengers to be carrying dynamite, not for any nefarious purposes, mind you, but as a tool for mining. And there was a decent chance there was dynamite on board that night. The discovery of a clock near the explosion sparked questions, but a man from India was apparently carrying that clock and had it hooked up to his grip (which might've contained dynamite), according to the Nelson Daily News.

With that in mind, the Doukhobors formed a different theory: The heat of the car could've begun to melt the outside of the dynamite, exposing the nitroglycerin, and it wouldn't be crazy to assume some of the men were smoking. A bit of carelessness in that kind of situation would have easily led to an explosion.

A plot by the Canadian government?

As terrifying as it might seem, the theory definitely exists that the Canadian government — the British Columbian government, in particular — had a hand in Peter Verigin's death, and it isn't entirely without warrant.

The British Columbian government made no secret of the fact that it didn't like the Doukhobors. They would restrict their right to vote, refuse to recognize their marriages, and try to force their kids to attend state school (via the Doukhobor Genealogy Website). It wasn't really a great look, and James Mavor found it absolutely despicable. He noted that the government seemed to want to break up the Doukhobor community, forcing them into unfavorable circumstances and refusing to pay them thousands of dollars they were owed. He even went so far as to compare the government to bandits and couldn't believe any Canadians were treated this way, much less people who were kind and welcoming.

The Doukhobors themselves definitely suspected the government, an open letter from them stating clearly that they thought the government intended to crush their community. In that letter, they cited the words of Justice Morrison during a court case: "The sooner that [the Doukhobor community] was squelched, the better." It's not incriminating, necessarily, but it's definitely cold, and the Nelson Daily News report on that case made it clear that the judge didn't care at all for the Doukhobors, seeing one of their cases as barely even worthy of the court.

An attack by Canadian nativists?

During the early part of the 20th century, nativist sentiment, native Canadians looking down upon those who immigrated there (via Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History and the Doukhobor Genealogy Website), ended up taking a greater hold in Canada.

And when it came to visible targets of sentiments like that, the Doukhobors were pretty high on the list. They largely kept to themselves and wanted to maintain their own culture, which could've looked threatening to native Canadians. Add to that the fact that they were officially exempted from military service, even during World War I, when plenty of other people were drafted regardless of what they wanted, and it's easy to say they weren't especially popular. At best, other Canadians thought of them as cowards. At worst, they were a menace.

An article from the Vancouver Sun illustrates the opinions surrounding the Doukhobors. The article is really about Verigin's consideration of moving back to Russia, but it ends with statements that the Canadian people would probably regard their departure as good news. They assumed that the Doukhobors would only create more problems in the future and would never assimilate into Canadian culture, only remaining a danger to the rest of the country.

The widespread contempt doesn't necessarily equate to Verigin's death, but it does seem to provide a motive.

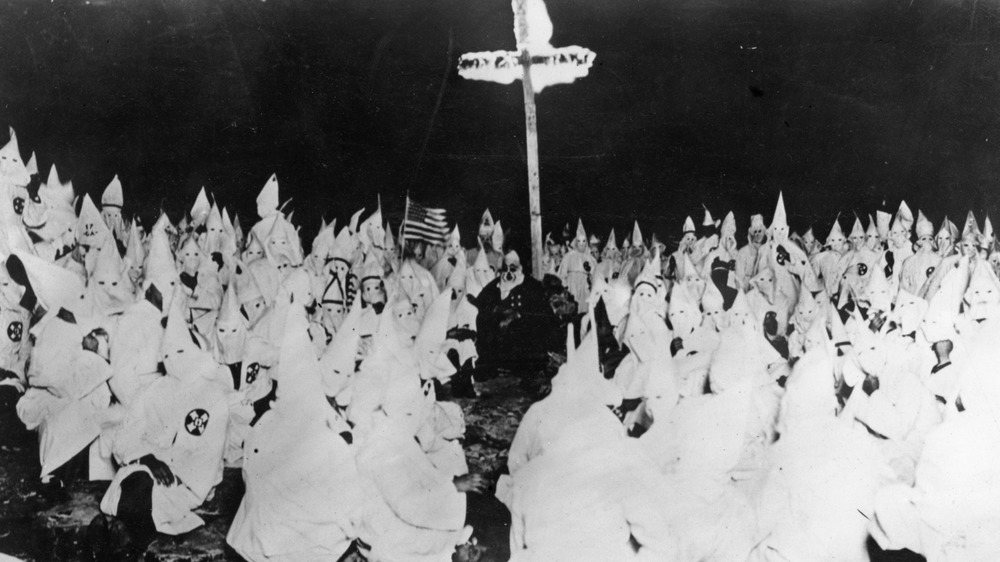

A result of KKK activity?

Maybe it's possible that Peter Verigin's death actually came from forces outside of the Canadian border. Maybe the explosion that killed Verigin was planned by an American group, namely the Ku Klux Klan or the American Legion.

A lot of this theory stems from the fact that Verigin had bought some land in Oregon — about 875 acres, according to the Oregon Daily Journal — in early 1924. Verigin never intended to actually move into America and start up a Doukhobor colony: It was just an investment and agricultural experiment. Only five people were there, and that was the extent of any American Doukhobor colony.

Nevertheless, there was a fear of these Russian "communists," especially in the early 20th century, so the purchase didn't go unnoticed (via the Doukhobor Genealogy Website). A telegram that can be traced to the American Legion speaks to a deep suspicion of the Doukhobors, wondering if they were "desirable" and also containing an ominous line: "I shall be glad if you will kindly take what action you deem necessary in the matter."

That doesn't mean any actions were taken, but there was also the KKK to consider, and official letters made mention of a known KKK leader trying to rally people in British Columbia in the 1920s. The intent was assumed to be violent, and the messages were hyper-patriotic in a way that definitely concerned Canadian officials. Maybe the KKK operating in British Columbia at the time was just coincidental, but it does raise questions.

Soviet involvement?

Saying that Peter Verigin was an important figure in the Doukhobor community would undersell the influence he had. D. Pavlov mentioned Verigin being called "a little tsar," and it's a pretty accurate description. He usually saw to it that matters resolved in his favor, and he had a lot of sway in what the community ultimately did. It's something the Soviet government would've been aware of.

After the February Revolution, talks began of the Doukhobors returning to Russia. After all, the Doukhobors were known as incredible farmers who knew how to work the land. That would be a huge asset to the new Russian government (via the Doukhobor Genealogy Website). Verigin was thrilled by the idea.

But with the October Revolution and the rise of the Bolsheviks, Verigin completely changed his mind, doing everything he could to avoid returning to Russia. That didn't change the fact that some of the Doukhobors wanted to return to their homeland, or the Soviet interest in their abilities. Skilled farmers were skilled farmers, after all. Verigin stood in their way, and getting rid of him could shift the future of the Doukhobors dramatically.

There were even theories given by the Kootenay Committee suggesting that the Soviets had tried to cover up their part by pushing the belief that the Canadian government was to blame. Maybe that's a stretch, but the Soviets were a legitimate suspect.

Dissent from within the Doukhobors?

There's the very real possibility that Peter Verigin's death was planned from within the Doukhobor community itself, because he did have more than a few enemies among his own people.

Early on in the creation of the Doukhobor community in Canada, a couple of factions began to form. The Independents had already broken from the main Doukhobor group, individually registering their homes with the Canadian government and thus pledging allegiance to the Crown, an act which Verigin openly disapproved of (via Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History and Dictionary of Canadian Biography). In general, they were looking toward the prosperity Canada could bring, feeling that Verigin was stifling their ambitions (via the Doukhobor Genealogy Website).

Then there were the Sons of Freedom, a purist, radical group of zealots who weren't afraid to make their views public. They rejected any sign of modernity and took to violent protests, burning down Verigin's home and Doukhobor-built schools and running around in the nude. Verigin condemned their actions, and the feeling was apparently mutual.

Even within the most faithful, there was room for corruption. Verigin's inner circle was composed of managers who held some amount of wealth and power in the commune. They were ready to support Verigin, so long as he worked in their interests, but it's not out of the question to think they might want his position for themselves or at least see him as an obstacle to their desires.

An act of patricide?

One of the more recent theories is that Peter Verigin was killed by his own son, and it does hold some water. Before being exiled in 1887, Verigin was married and had a son, both of whom he left and maintained a precarious relationship with, to put it lightly.

A violent drunkard and gambler with a brutal personality and a harsh temper, Peter Petrovich Verigin (later known as "Chistiakov") made his hatred of his father obvious (via Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History). On a visit to Canada in 1905, he was heard arguing with his father, calling him a "crook and bandit, liar and cheat," and an "old reprobate" who only had an eye for young girls (via the Doukhobor Genealogy Website). Interviews with those who knew him also revealed his threats to destroy his father's work, because he was certain that his time would come soon.

And he was sort of right, on that front. After his father's death, Chistiakov was called back to Canada to become the Doukhobor leader, and he was determined to act on his hatred, proclaiming that he was ready to disgrace his father. Under his watch, the commune crumbled and fell apart, fully dismantled by 1938. Murderer or not, Chistiakov did achieve his goals.