The Crazy True Story Of The Tokyo Subway Sarin-Gas Attack

The 1995 sarin gas attacks in Tokyo were one of the first attacks perpetrated on a public transit system. Targeting one of the busiest transit systems in the world, it was only due to the incompetence of the Aum Shinrikyo cult members who carried it out that the attack wasn't any more horrific than it was.

The attack was a living nightmare, with people coughing up blood and convulsing in their seats. And tragically, this wasn't the Aum Shinrikyo's first attack, and police were slowly connecting the dots when the attack in March 1995 occurred.

Members of the cult were rounded up after the attack and after 20 years of trials, all but one of those who were indicted were convicted. Shoko Asahara, the founder of the cult, along with six members who were responsible for the 1995 attack, were sentenced to death by hanging and executed in 2018. Asahara, once a guest on TV variety shows, ended up becoming known as the person responsible for "the worst terrorist incident on Japanese soil." And for many, the horrors of the 1995 Tokyo subway sarin attack linger to this day. This is the crazy true story of the Tokyo subway sarin-gas attack.

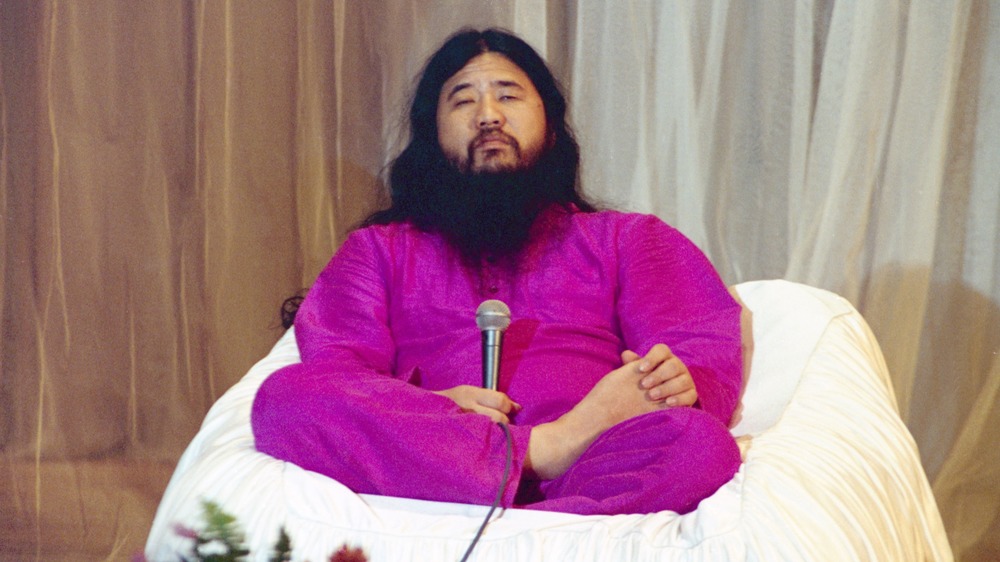

Who was Shoko Asahara?

Shoko Asahara was born Matsumoto Chizuo on March 2, 1955 in Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan. The Japan Times reports that Asahara was the sixth child out of seven children, and his parents ran a tatami shop.

Asahara was visually impaired due to infantile glaucoma and was placed into the Kumamoto Prefectural School for the Blind. After he was unable to gain admission to medical school, Asahara began studying acupuncture and pharmacology, seemingly on his own. He also married Tomoko Ishii, a local college student, in 1977-78, with whom he eventually had six children. According to "A Case Study on the Aum Shinrikyo," in 1982, Asahara was arrested under the suspicion that his pharmacy was "violating Japanese pharmaceutical laws... for selling unregulated medicines." Although it doesn't seem that he was imprisoned for the offense, his pharmacy went bankrupt soon after Asahara was arrested.

Other than this, not much is known about Asahara's early life. Although some claim that Asahara traveled widely for his religious training before starting Aum Shinrikyo, there's little evidence to support this.

What is Aum Shinrikyo?

Shoko Asahara started studying yoga in 1977 and seven years later, he opened his own yoga training school called Aum no Kai, which translates to "Aum's Group." According to "A Case Study on the Aum Shinrikyo," the yoga school was also a publishing house. Asahara changed his own name in 1986 and the following year, the group was renamed Aum Shinrikyo, which translates roughly to mean "supreme truth." By this point, Asahara's ideology for Aum Shinrikyo was beginning to coalesce.

According to "Aum Shinrikyo," the cult's ideology mashed together concepts from Hinduism and Buddhism along with ideas of a Christian hell and Armageddon, plus a few sprinkles of Nostradamus's writings. Asahara was also considered pivotal to Aum Shinrikyo, who believed that he was the first "enlightened one" since the Buddha. The guiding belief of Aum Shinrikyo was based around the idea that "there is an eminent war between good and evil, and killing those who stand in the way of the supreme truth is justified, and that this supreme truth was possessed solely by Shoko Asahara." They also preached that they would be the only ones to survive the upcoming apocalypse, which Asahara predicted would occur either "in 1996 or between 1999 and 2003."

Aum Shinrikyo targeted top engineering, chemistry, and physics students from Japanese universities, made relationships with the yakuza and the KGB, and even recruited medical doctors.

Giving Aum Shinrikyo legal status

In August 1989, Aum Shinrikyo was given official status as a religious corporation by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government in Japan. And by this point, according to Encyclopedia Britannica, Shoko Asahara had already started calling himself "Tokyo's Christ," "Holy Pope," and "Savior of the Century." "A Case Study on the Aum Shinrikyo" notes that this recognition gave Aum Shinrikyo several advantages, "including massive tax breaks." It also offered immunity from oversight since "under the Japanese Religious Corporation Law, after a group is recognized, authorities are not permitted to investigate its 'religious activities or doctrine.'"

It was later revealed that Aum Shinrikyo gained its religious status through "an aggressive lobbying campaign," but once it was legally recognized, the character of the cult changed drastically.

Its membership also soared after its legal recognition. Aum Shinrikyo turned from a small group to an organization with 10,000 members in 1992, by their own accounts. By 1995, that number had grown to 50,000 members worldwide, with offices in Japan, Russia, and the United States, among other countries. The net worth of the cult also skyrocketed from approximately $4.3 million in 1989 to $1 billion by 1995. According to CFR, Aum Shinrikyo's astronomical financial growth came from the fact that they recruited "young, smart university students and graduates, often from elite families," and they required members "to sign their estates over to the group."

Testing sarin-gas attacks

On June 27, 1994, there was a sarin attack in Matsumoto, Japan between 10:40 and 10:50 pm. Reuters reports that a refrigerator truck was used to release the gas, spraying vaporized sarin for approximately 10 minutes towards the houses of three judges. "A Case Study on the Aum Shinrikyo" writes that these judges were targeted since they were presiding over a land fraud case that Aum Shinrikyo was involved in. The verdict was set to be released in mid-July, and Aum Shinrikyo "decided to target the three judges hearing the case in order to prevent them from returning a decision against the Aum."

All three of the judges fell ill as a result, but a breeze also blew the sarin cloud into a different neighborhood that ended up being heavily affected. Seven people died as a result of sarin poisoning, one woman was left comatose, and roughly 600 people "were affected by the agent."

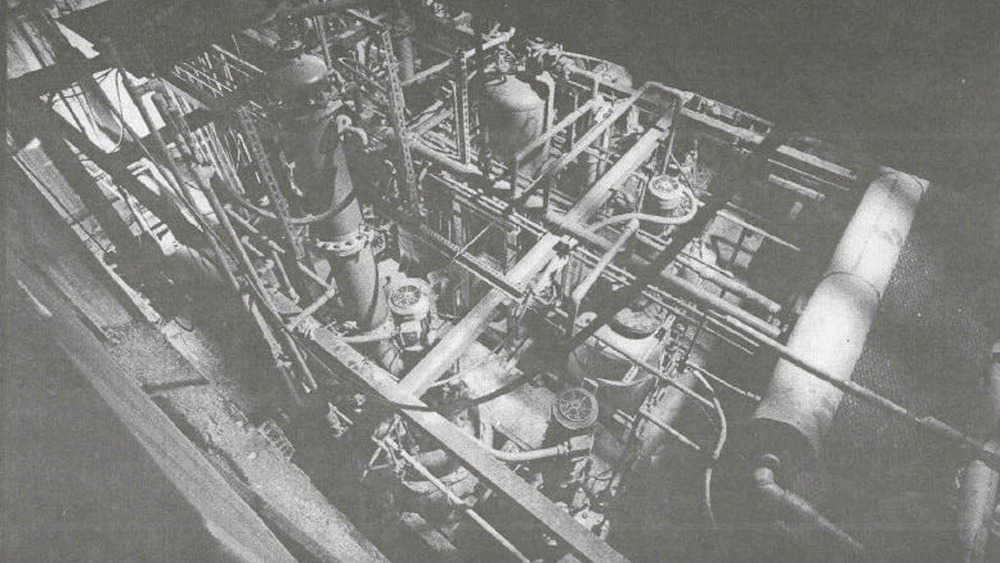

Members of Aum Shinrikyo later admitted that the attack had essentially been a test run for their attack the following year. It's also not as though these activities went entirely unnoticed by the police. Two weeks after the sarin attack in Matsumoto, there was a sarin spill at Aum Shinrikyo's Kamikuishiki facility in their compound (pictured). Police were called to the scene since there was a "strong and strange odor that allegedly killed vegetation near the Aum compound," but when they were refused entrance, the police simply left and didn't pursue the matter.

The Tokyo subway sarin-gas attack happened during morning rush hour

However, while the Matsumoto attack was aimed at a particular group of people, the Tokyo subway attack of 1995 appeared to be an indiscriminate attack on civilians. Aum Shinrikyo's plan involved putting 11 containers of sarin on five different trains than ran on the Chiyoda, Hibiya, and Marunouchi lines of the Tokyo subway system, a metro that has "over five million riders daily," according to "A Case Study on the Aum Shinrikyo."

The Japan Times reports that a little before 8 am on March 20, 1995, five members of Aum Shinrikyo boarded the three subway lines with the bags of sarin. Ikuo Hayashi went on the Chiyoda line, Kenichi Hirose and Toru Toyoda went on the Marunouchi line, and Masato Yokoyama and Yasuo Hayashi went on the Hibiya line.

At a coordinated time, all the attackers poked a hole in the bag of sarin with their sharpened umbrella tip and ran out of the train as the doors closed behind them. As the liquid sarin vaporized, the passengers on the train started to immediately get sick from the fumes. But as sick passengers ran off the train, the trains continued to run and "the fumes were spread at each stop, either by emanating from the tainted cars themselves or through contact with liquid contaminating peoples' clothing and shoes," writes Encyclopedia Britannica.

Catastrophic chaos

Thirteen people died as a result of the sarin attack and over 6,000 more people were left injured. Among those who died were two subway workers who tried to get rid of the sarin bags at Kasumigaseki Station. And many suffered exposure in their attempts to help those who were already exposed. The Japan Times reports in 2020, at least one-third of the survivors of the sarin attack suffer from PTSD caused by the attack, in addition to various physical health complications.

And apparently, according to "A Case Study on the Aum Shinrikyo," it was pure luck that the attack wasn't any worse. The sarin happened to be of "poor quality" and had an "inadequate delivery system," and if it weren't for these mistakes, thousands more could have been killed and injured.

It's also believed that the attack wasn't as chaotic as it might have appeared. Since all the trains were meant to go to Kasumigaseki station, it was once thought that the government bureaucrats who worked there were the targets. However, it's now believed by the Japanese government that the gas attack was meant to be a diversion to overwhelm the police, since they were already planning a raid of Aum Shinrikyo in search of a kidnapped notary, and the cult likely wanted time to destroy evidence.

Hundreds of arrests

Between March 22nd and September 4th, there were over 500 raids by the police in almost 300 different locations. According to The Japan Times, the first raid was at the Aum Shinrikyo compound in Yamanashi Prefecture. Police claimed that they were looking for the kidnapped notary, but when they showed up at the compound wearing hazmat suits it became clear what was really going on. At the compound, police found "equipment used to make sarin and other biological weapons, helicopters for use in gas attacks, weapons, and illegal drugs."

According to "A Case Study on the Aum Shinrikyo," over six months, between 400 to 500 Aum Shinrikyo members ended up being arrested, encompassing "almost the entire hierarchy of the cult." Shoko Asahara wasn't arrested until May 16th, when he was found "hiding in a wall recess along with a pile of cash and a sleeping bag." The same day, the Governor of Metropolitan Tokyo received a letter bomb from Aum Shinrikyo that "exploded in the hands of his secretary, blowing off the fingers of his left hand."

Overall, at least 200 Aum Shinrikyo members ended up being indicted.

Failed attempts with hydrogen cyanide

After the sarin attack in March, Aum Shinrikyo attempted and failed to commit several more gas attacks, this time with hydrogen cyanide. "A Case Study on the Aum Shinrikyo" writes that the first attempted attack occurred on May 5, 1995. This time, Aum Shunrikyo targeted Shinjuku station, and put two plastic bags in a public bathroom, "one containing two liters of powdered sodium cyanide and the other containing about 1.5 liters of diluted sulfuric acid." When the bags were found, they were already on fire but hadn't broken open yet. If they had, they would've created hydrogen cyanide gas, and it's estimated that the gas created "would have been sufficient to kill between 10,000 and 20,000 people."

The second attempt occurred on July 4, 1995, but this time there were four dispersal devices in the public restrooms at the Ginza, Tokyo, and Kayabacho subway stations and the Japanese Railway Shinjuku station. This gas attack was similarly averted.

According to the Center for a New American Security, Aum Shinrikyo had also planned a hydrogen cyanide gas attack on May 3rd, but they'd abandoned it before the dispersal device was set up.

Criminal activity leading up to the Tokyo subway sarin-gas attack

After police finally started investigating Aum Shinrikyo, it became clear that they weren't doing a great job of hiding their criminality. As early as 1989, families of Aum Shinrikyo members were reporting to police that Aum Shinrikyo was assaulting and kidnapping people.

"A Case Study on the Aum Shinrikyo" records that in September 1993, two members of Aum Shinrikyo pled guilty to "carrying dangerous chemicals on an airplane in Perth, Australia." According to Vice, Aum Shinrikyo had gone to West Australia "looking for a place they could test chemical weapons without interruption" in April 1993, but it's not unlikely that the conviction of their members led to them fleeing the country in October 1994.

At one point, Aum Shinrikyo members were even sent to Zaire, now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to get a sample of the Ebola virus in 1992, although they were unsuccessful, according to the Federation of American Scientists. Aum Shinrikyo members were involved in numerous burglaries and robberies over the years, including ones at the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department, the Hiroshima Factory of the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, and Nippon Electronics Co. Aum Shinrikyo members were also responsible for several murders, though many of the bodies weren't found because they were reportedly burned in an incinerator. Hiroyuki Nagaoka, the head of the Association of the Victims of Aum Shinrikyo, was also the victim of a gas attack by Aum Shinrikyo, although he managed to survive.

Revelation of the Sakamoto family murder

After arresting various cult members, police also discovered that Aum Shinrikyo was responsible for the 1989 disappearance of the Sakamoto family. The New York Times reports that Tsutsumi Sakamoto, his wife Satoko, and their 1-year-old child Tatsuhiko had disappeared in November 1989, but despite the fact that people suspected that the cult had something to do with it, "police apparently did not pursue leads linked to the cult, perhaps in part because they were worried about infringing on the rights of a religious group."

But after Aum Shinrikyo members were arrested after the 1995 sarin attack in Tokyo, some revealed information to the police that led them to the remains of the Sakamotos, although they were unable to find the remains of the infant.

The family was reportedly murdered on November 4, 1989, due to orders from Shoko Asahara. The Japan Times writes that Sakamoto, an anti-cult lawyer in Yokohama, had apparently claimed that Aum Shinrikyo had "kidnapped a relative of his client," which is what led the cult to retaliate. And despite the fact that the family had disappeared during the night with "some bedding but no clothing, and an Aum badge was found in their home, police treated their disappearance as a missing persons case" instead of a murder.

The Aum Shinrikyo trials

The trials of the Aum Shinrikyo members lasted almost 20 years in total. According to The Japan Times, all but one of the cult members who were taken to trial were convicted, with sentences ranging from a few years to life imprisonment. Thirteen members were sentenced to death, including those responsible for the 1995 Tokyo attacks. However, Ikuo Hayashi, who was responsible for the Chiyoda line attack, was sentenced to life in prison due to his cooperation with the police.

On December 15, 1995, a Cold War-era law was invoked by Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama in order to disband Aum Shinrikyo. For some social activists, this action was seen as unconstitutional.

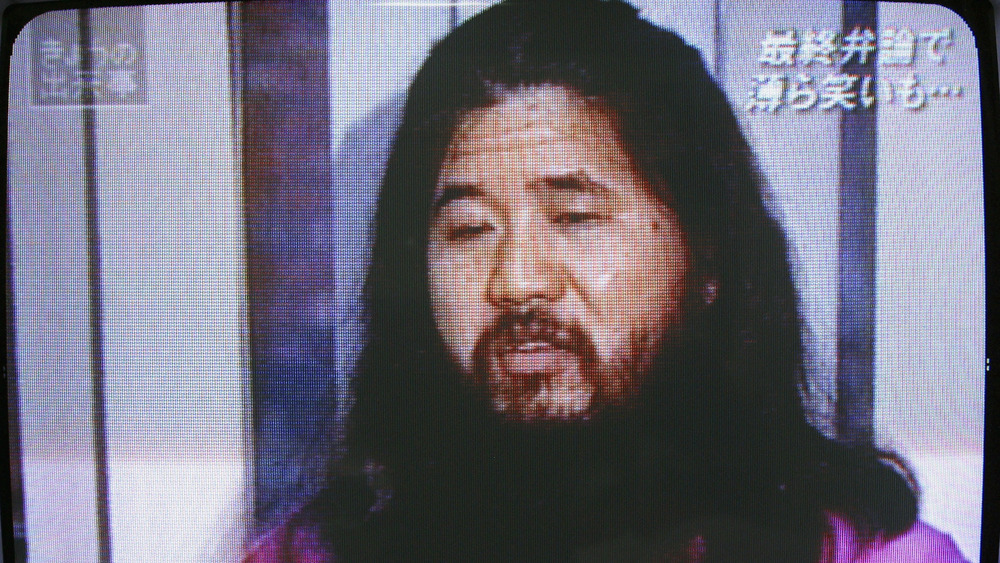

Shoko Asahara's own trial started in 1996 and lasted eight years, during which he "refused to answer questions and [never] made more than confusing comments." Murderpedia also writes that Asahara often "mumbled incoherently and continually interrupted the testimony." On February 27, 2004, Asahara was sentenced to death by hanging. Although his lawyers immediately appealed, the Tokyo District Court twice rejected pleas for retrials.

Death by hanging

Thirteen cult members, including Shoko Asahara, were sentenced to death by hanging. However, due to the various appeals and the many trials of all the cult members, the executions were repeatedly delayed, since "the Justice Ministry has made it a custom to postpone the execution of death-row inmates if proceedings against their accomplices are ongoing," writes The Japan Times.

As a result, the cult members waited on death row until July 6, 2018, when Japan began executing the Aum Shinrikyo members, beginning with Asahara, according to The Guardian, who was executed by hanging. By July 28th, the remaining cult members were all executed.

Despite the fact that the death penalty is rarely used in Japan, approval for capital punishment is high, and many advocated for the execution of the Aum Shinrikyo members. The BBC reports that Atsushi Sakahara, a film director caught in the 1995 attack, said, "It will be impossible to ever forget the incident, but the execution brings a kind of closure."

So what happened to Aum Shinrikyo?

After the arrest of most of Aum Shinrikyo's hierarchy, some members fled to Russia, while others stayed in Japan and tried to practice without persecution. But at this point, governments weren't as friendly with Aum Shinrikyo as they'd been before.

The Guardian writes that although Aum Shinrikyo was banned, it reemerged in 2000 with the name Aleph, "whose members claimed they had disowned Asahara and agreed to pay compensation to the gas attack victims." (In 2019, they were taken up on this offer when they were ordered by a Tokyo court to pay $9.5 million in damages to the victims of the 1995 sarin attack, per The Japan Times.) However, some claim that Aleph members continue to follow the teachings of Shoko Asahara and have even kept "audio recordings of his voice for inspiration."

Aleph's members live in a headquarters in the suburbs of Tokyo, but this headquarters is kept under surveillance. Another group, Hikari no Wa, that splintered off from Aum Shinrikyo is also kept under government surveillance as of 2019.