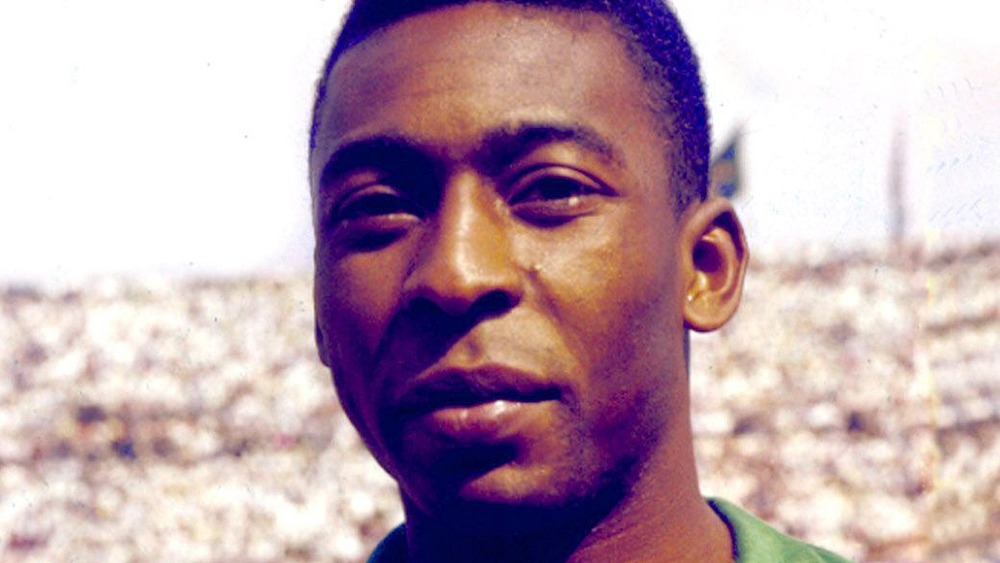

12 Pele Facts Only The Biggest Soccer Fans Knew About Him

A handful of athletes move beyond their period as a dominant figure in their sport to the status of worldwide immortal. These are the so-called "greatest of all time," people like Michael Jordan, Tom Brady, and Serena Williams. And then there's Pelé, probably the most famous and influential individual sportsman the world has ever seen.

Even people who have never watched a second of soccer have heard of Pelé. Over a 22-year period stretching from the mid-1950s to the late 1970s — which included stints for pro teams in Brazil and the U.S. and a leading role on the Brazilian national squad — Pelé scored an astounding 1,281 goals in 1,363 games, according to the soccer organization FIFA. He led Brazil to three World Cup titles at the pro level, too. When all was said and done, he was a towering figure, a celebrity, and even a role model to millions, almost universally regarded as the best to ever play soccer (a.k.a. football).

Sadly, Pelé died on December 29, 2022, aged 82, CNN reported. He'd been diagnosed with colon cancer the previous year. Here's a look into the fascinating, dazzling, and utterly kicking life of Pelé.

How Edson became Pelé

In 1940, Pelé came into the world as Edson Arantes do Nascimento. According to The Guardian, his parents named him after American inventor and industrialist Thomas Edison, which the future soccer star enjoyed. "I was really proud that I was named after Thomas Edison and wanted to be called Edson." The first informal name bestowed upon him was "Dico," thought up by an uncle and by which his mother referred to him for his entire life. When he went pro for the Brazilian team Santos, other players called him Gasolina, the name of a popular local singer of the 1950s. That one only briefly usurped Nascimento's inescapable moniker: Pelé, which he accidentally adopted as a child and hated when other kids used it. "On one occasion, I punched a classmate because of it and earned a two-day suspension," he said.

But what does it mean? Pelé wasn't completely sure, but he thought its origin lay with a teammate of his father's, who played semi-pro soccer. Jose Lino was known as "Bilé," the first word he said as a toddler after a group of witch doctors hired by his mother tried to get him to speak. When young Pelé saw Bilé play, he couldn't say the name properly, and it came out as "Pilé," or "Pelé."

Before he was Pelé, he was a Shoeless One

Not yet known as Pelé, Edson Arantes do Nascimento was born in 1940 in the economically depressed Tres Coracoes in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais (via JRank). Early on, he showed an affinity for and an interest in soccer (his father, after all, had played some soccer for a series of smaller clubs), but his parents were unable to afford to buy the younger Nascimento a soccer ball. Instead, his father found a disused old stock and stuffed it until it was almost bursting with rags. That became Pelé's soccer ball, and he'd run through the streets of Tres Coracoes, kicking the makeshift ball as he did and building up his prodigious skills.

When Nascimento was six, the family moved to the larger railroad town Bauru in southern Brazil. To earn money to buy a manufactured soccer ball, Nascimento worked as a peanut vendor and shoe-shiner. When he wasn't doing that, he formed a team with his equally soccer-mad friends called The Shoeless Ones, and they played in vacant lots or in the middle of the street — barefoot, because all of the kids came from families that couldn't afford shoes. Pelé learned how to play soccer for real as one of The Shoeless Ones, while barefoot soccer later developed into a widely played variant known as pelada – named for Pelé.

Pelé was a phenom

In his early teen years, Pelé landed a spot on a youth soccer team coached by Waldemar de Brito, a Brazilian soccer star and one-time member of the Brazilian national team. By the time Pelé was 15, his coach and mentor thought his charge was ready for the big time. According to FourFourTwo, de Brito gave a hard, aggrandizing sell, telling the leaders of Santos, a major Brazilian pro team, that while Pelé was good, he would soon develop into "the greatest football player in the world." He proved de Brito right, and he started showing his mettle right away. In his first full season with Santos – going pro at the age of 15 — Pelé led the team in scoring. Before long, he'd helped the squad secure several regional, state, national, and continental titles.

Pelé played so well he joined the Brazilian national team, and by the time he was 17, he'd led the squad to a World Cup championship. He's still the youngest player to ever score in soccer's biggest global tournament and the youngest to win the whole thing, too.

The real reason why Pelé never played in Europe

Between 1958 and 1970, Pelé played in four World Cup tournaments — and winning three times — starring on the national team from his home country of Brazil. During that same time, and a little bit before and after, he played professionally, too, for Santos FC, a top-shelf club based in the Brazilian city of Vila Belmiro. However, during his two-decade career peak, from roughly 1956 to 1974, Pelé never played for a pro squad in Europe, which, at the time, offered the highest-profile teams and leagues and paid the highest salaries worldwide for soccer players. Pelé likely would've been a big star (and major fan draw) in the likes of the U.K.'s Premier League, Italy's Serie A, or Spain's La Liga, but he was legally prohibited from even signing with a European team.

According to These Football Times, Real Madrid, Manchester United, and Juventus all made big offers to Pelé, with the latter reportedly including a large ownership share in the Fiat car company if he signed. Brazilian president Janio Quadros, an unpopular figure, decided to prevent Pelé's departure and boost his own approval ratings by passing a law that named Pelé an official national treasure. In Brazil, such a law prevents export — meaning Pelé couldn't leave for Europe.

Pelé launched the era of big shoe money

Shoe deals are a common part of professional sports in the 21st century. Ever since Michael Jordan launched his Air Jordan line in the 1980s, seemingly every major athlete gets their own signature shoe or is paid a lot of money to endorse an existing line. Shoe companies jockeying to align with particular athletes goes back to the mid-20th century, with Adidas and Puma the primary players. Just before the 1970 World Cup, according to the Los Angeles Times, the firms agreed to a "Pelé Pact," with both agreeing to not pursue Pelé, as a bidding war would have taken figures so high that it would have been financially catastrophic for whoever won.

Pelé was unaware of the pact and instead signed with Stylo, a tiny U.K.-based shoe company. However, Hans Henningsen, a sports reporter friendly with Pelé, also worked for Puma. Without the knowledge of his superiors, he offered Pelé $25,000 to wear his company's shoes in the World Cup, plus another $100,000 to wear them for four more years, as well as a portion of the income generated from Pelé-branded sneakers. Then, they worked out a deal for Pelé to show off his fresh kicks. As he'd previously agreed to do so, Pelé asked for a brief timeout before the beginning of the 1970 World Cup final, and he bent down to slowly tie his shoes. TV cameras dutifully zoomed in on Pelé tying his sneakers, bearing the Puma logo.

Pelé popularized the jersey swap

The jersey swap is one of the most oddly heartwarming traditions in sports. In a show of both good sportsmanship and mutual admiration at the conclusion of a game, a star player will remove the shirt part of their uniform they just played in, caked with sweat and mud, and trade it with a player of equal stature on the other team. The National Soccer Hall of Fame told The Washington Post that the ritual started in soccer, and in earnest, at the 1954 World Cup in Switzerland.

Jersey swapping took off in modern American sports (it's especially common in the NBA) because of Pelé. In a 1970 World Cup match, Brazil beat England 1-0, and at the conclusion, Brazil's Pelé traded jerseys with England's captain Bobby Moore, and the two hugged. It was one of the most indelible moments of the entire tournament, and five years later, dozens of Major League Soccer players wanted to recreate that moment and have their own special jersey swap with the most admired player on the planet. When Pelé joined the New York Cosmos, the team's equipment manager made sure that every player on every opposing team got a Pelé No. 10 Cosmos jersey after the match.

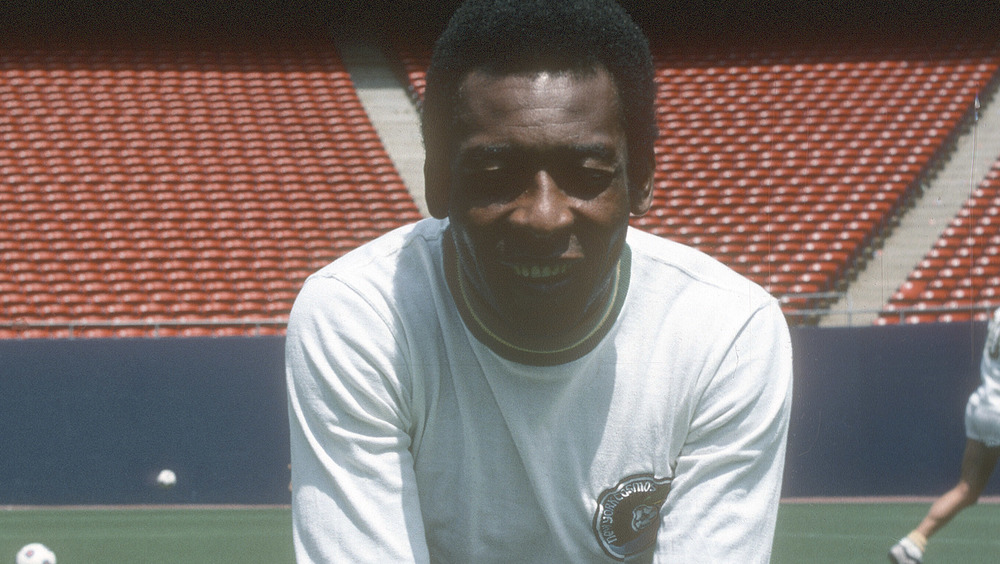

When Pelé came to America

Despite being a living, breathing, non-exportable resource of Brazil, Pelé got around those rules in 1975 when he signed with the New York Cosmos of the North American Soccer League. The seven-year-old NASL was the top pro soccer league in the U.S., and it made big moves to establish itself in the same tier as the NFL or NBA. Securing the world's best soccer player was certainly a step in the right direction. According to The New York Times, Pelé agreed to a three-year contract worth $7 million, making him the highest-paid team-sport athlete on the planet. Not only was landing Pelé a major PR boon for the NASL, but his presence could explicitly promote the league, too — the contract allowed Cosmos owners to use Pelé's name and image in commercials.

Still, when Pelé moved to American soccer, he wasn't at his athletic peak. According to ESPN, the veteran of nearly 20 years of high-level soccer was 34 years old and had semi-retired, having not played a game in almost a year. Still, just the allure of Pelé was very strong. In his first match, a June 1975 contest against the Dallas Tornado, Pelé grabbed one goal and one assist and was seen by ten million TV viewers — a record for soccer in the U.S. By the end of the season, Cosmos attendance figures tripled, and by the time Pelé left the NASL in 1977, attendance for the entire league had doubled.

Pelé the movie star

Pelé was more than just a soccer player — he was a living legend, known in almost every country on Earth, wherever soccer was even moderately popular. He transcended sports into celebrity, and by the time his playing days were winding down in the '70s, he'd already launched what would become a modestly successful career in movies. In the 1971 Brazilian comedy "O Barão Otelo no Barato dos Bilhões", Pelé played the dual roles of a doctor and himself. A year later, he took on a starring role in the drama "A Marcha." After he retired from playing soccer, he had more time for other things, and he not only played himself in 1980's "Os Trombadinhas," but he also wrote and produced the movie, a treacly story about saving orphan pickpockets from the streets of São Paulo. In 1983, Pelé played himself again in "A Minor Miracle," another rescue-the-orphans movie, and returned to writing again with the 1986 family soccer comedy "Os Trapalhões e o Rei do Futebol", wherein he plays a character named Nascimento (his real last name).

Probably Pelé's biggest movie role came in the 1981 World War II film "Victory." In the story of Allied prisoners of war playing a soccer game against the German National Team in Nazi-occupied France, Pelé played Luis Fernandez, a soldier who happens to be a great soccer player. He had third billing on Victory, right after Sylvester Stallone and Michael Caine.

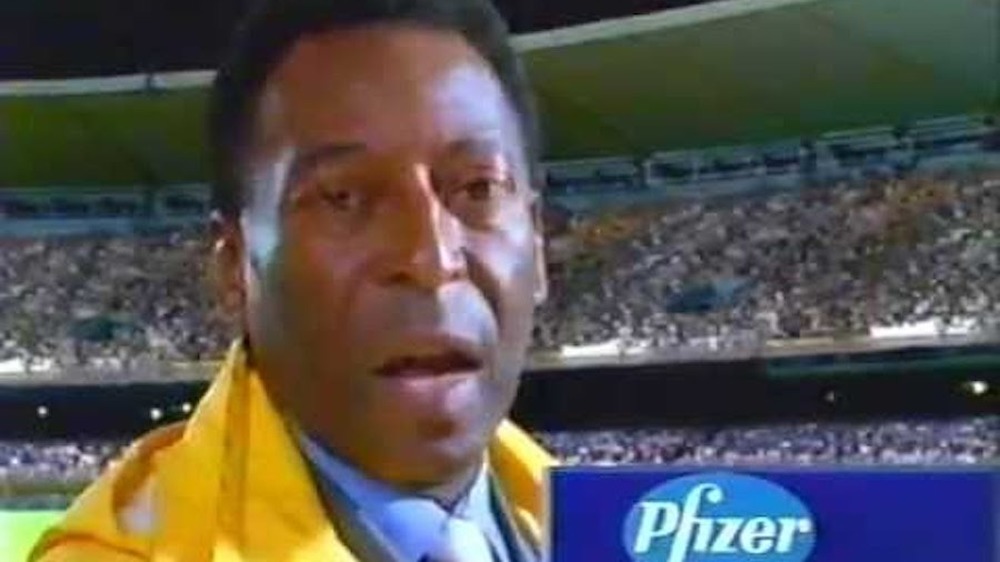

Pelé helped with male sexuality issues

Like many prominent athletes, Pelé made a lot of money from endorsement deals. Among the brands that the soccer legend was paid to promote, according to Forbes, were Volkswagen, Procter & Gamble, Emirates, and Subway. Pelé's advertising gigs continued long after his playing days ended, too. In 2002, according to the Irish Independent, some 25 years after he retired from league play, Pelé took on a paid position as a brand ambassador for the pharmaceutical company Pfizer. His purpose was to use his celebrity and stature to raise awareness of erectile dysfunction and how the company's drug, Viagra, could treat that issue. In doing this job, and appearing in Viagra commercials, Pelé helped break the stigma of discussing male health issues in traditionally macho cultures, namely diminished sexual drive and the inability to perform.

He may have done too good of a job. In 2003, according to the Sports Business Journal, the government of Pelé's home country of Brazil banned the advertising of E.D. drugs — including ones for Viagra, featuring Pelé — due to a rise in illegal, unprescribed use of such medications by young people.

Pelé got tied up in an embezzlement scandal

Not even a figure as larger-than-life as Pelé was immune to scandal. According to The Guardian, in 1995, he was named Brazil's Extraordinary Minister of Sports, which allowed him to generate legislation to break up the shady corporate alliances prominent in Brazilian soccer at the time, which he'd publicly denounced for years. Critics, however, suggested that Pelé personally benefited from de-corruption, because a lot of soccer-related businesses had to turn to new partners: like companies Pelé controlled, such as Pelé Sports & Marketing.

For example, in 1995, the international humanitarian aid charity UNICEF contracted with PSM to stage a fundraiser soccer game in Argentina. That match was ultimately cancelled, but UNICEF didn't get its money back, and $700,000 of it disappeared from the company's accounts. Pelé blamed his business partner Helio Viana, who he had suspected for years of embezzling around $10 million from their organization. While Pelé was found to be innocent of any wrongdoing, his association with crooks severely damaged his reputation. "Pelé has had problems with his business partners before, but he cannot claim ingenuousness anymore," said Brazilian sports journalist Juca Kfuri. "People used to excuse him by saying, 'Look, Pelé is young, he is naive, he had a poor upbringing.' This is fine when he is aged 20, but at 61..."

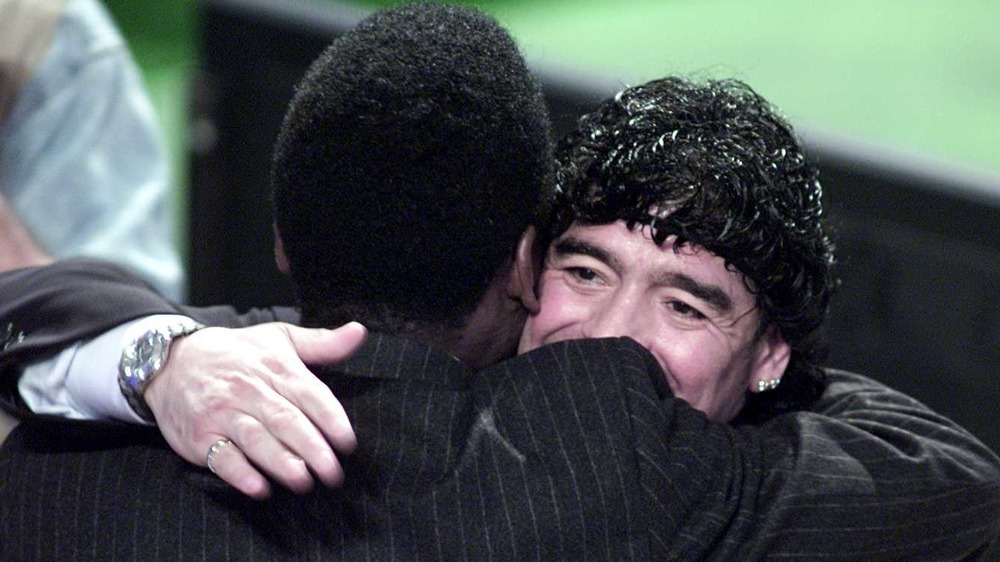

Pelé vs. Maradona

In 2000, FIFA, the worldwide soccer governing body, named its best player of the century, or players, rather: Pelé and Argentinian icon Diego Maradona. Both scored hundred of goals in national team and professional play and won a World Cup, and debate endures to this day about which athlete is soccer's true greatest of all time. It's lonely at the top, however, as there was no love lost between the two icons.

After Pelé sat for an interview during the 2010 World Cup, Maradona said that "Pelé should return to the museum." After Pelé asserted that X Neymar was a superior player to Lionel Messi, Maradona said that Pelé "took the wrong pill. Instead of taking the pill before bedtime he took his morning pill. He got confused." On another occasion, Maradona resented being compared to Pelé "because of the stupid things he says." As for the other side of this argument, Pelé casually asserted that he was just plain better than Maradona, and all arguments to the contrary are irrelevant: "All you have to do is look at the facts." (They resolved their feud before Maradona died in 2020.)

Heads up, it's Pelé

Pelé wasn't just the result of where an excellent athlete meets hype and charisma: His stats back up the claim that he's the greatest soccer player to ever hit the pitch. Among the many records he set: 92 hat tricks (games where he scored three goals), the most goals in Brazilian national team history, the most goals for the Brazilian pro team Santos, the most assists in the World Cup, and winning two World Cups by the time he was 21. His stats are off the charts, but Pelé's unique ability to make headers — scoring a goal by strategically bouncing the ball off of his noggin — was unmatched ... almost.

Pelé's father, soccer player Joao Ramos do Nascimento, or Don Dinho, had a knack for headers and once scored five in one match. "That was something brilliant," Pelé told India's Tribune in 2015. "I also tried hard but couldn't break his record." The closest he got was with four off-the-dome goals in a 1964 playoff game against Brazilian team Botafogo. However, in the 1970 World Cup final, Pelé scored Brazil's first goal of the game with a header, setting the stage for his team to win that global title match.