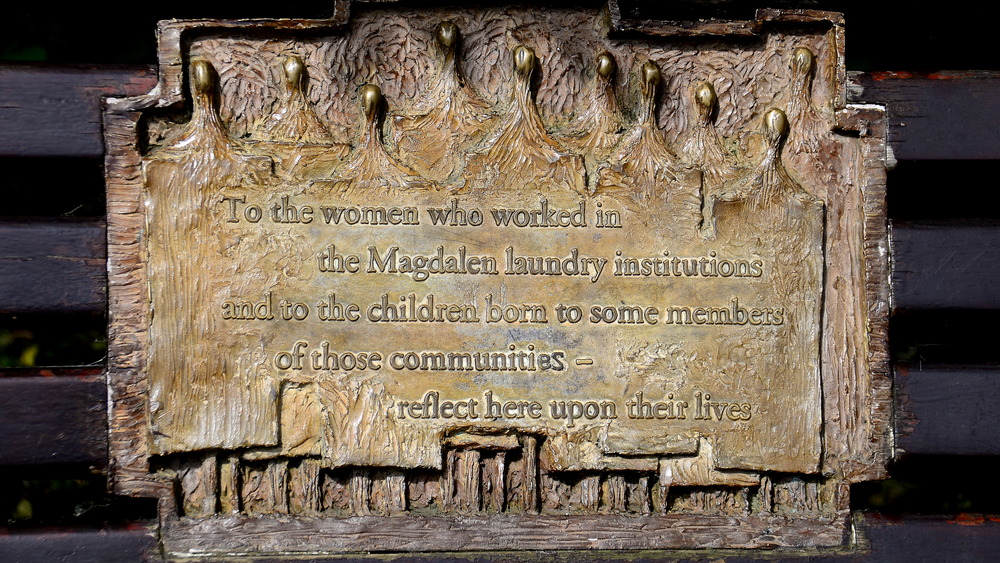

The Tragic Truth About Ireland's Magdalene Asylums

Throughout human history, people have often isolated and imprisoned those whom they deem to be defying societal expectations. The Magdalene asylums, more commonly known as Magdalene laundries, which operated mainly in Ireland throughout the 19th and 20th century, are one such example. Women as old as 89, girls as young as eight, and all those aged in between were shuttered into Magdalene laundries if they were in any way deemed an inconvenience to society. This happened if a girl or woman stole an apple, acted too sex-positive, was sexually abused by a relative, or was just in the wrong place at the wrong time. And those who ended up pregnant were often shipped off to mother and baby homes, which operated in conjunction with Magdalene laundries, although they were an independent, though equally horrific, institution.

It's believed that time spent in Magdalene laundries ranged from less than three months to 10 years, though often when women and children entered the Magdalene laundry they weren't told how long they were to remain there. While many Magdalene laundries were in Ireland, they also existed in Canada and Australia.

Although it's unclear how many people went through Magdalene laundries, estimates in the tens of thousands are considered to be under-representing the scale of this institution. And for many, like Mary Cavner, the trauma of the Magdalene laundries is difficult to forget, rendering some simply "unable to communicate properly" due to their experiences in the asylum. This is the tragic truth about Ireland's Magdalene asylums.

What were Magdalene laundries?

Although Magdalene convents existed in the medieval period, they operated more like half-way houses, with the intention of "retransition into society." But during the 16th and 17th century, the creation of the Poor Laws and the Factory Laws set the stage for the creation of Magdalene laundries, Rebecca Lea McCarthy writes in Origins of the Magdalene Laundries. The Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee to establish the facts of State involvement with the Magdalen Laundries states that the first Magdalene asylums in the United Kingdom were established in the mid-1700s. The first one in Ireland, known as the Dublin Magdalen Asylum on Lower Leeson Street, intended "to rescue first fall Protestant cases only." According to DW, after 1922, "when the Irish state was formed, the tendency was to rely on the church to provide social services." From 1922 to 1996, the remaining 10-12 Magdalene laundries in Ireland were run by four religious orders: the Good Shepherd Sisters, The Sisters of Our Lady of Charity, The Sisters of Mercy, the Sisters of Charity.

These asylums "included institutions of all denominations and none," though they were all geared towards "fallen" women. However, while "fallen" women in England were offered some tools in order to realize their "economic potential," Irish institutions believed it was impossible for a "fallen" woman to reenter society.

The name came from Mary Magdalene, a woman from the Gospels often presented as "fallen," and the fact that the Sisters ran "laundries for profit," which imprisoned women and girls worked without pay, according to The New York Times.

Imprisoning 'fallen women'

Magdalene laundries claimed that they were imprisoning women who were "promiscuous," "unwed mothers," or even the daughter of an unwed mother," but in reality they were imprisoning any and all women who resisted the status quo. There's "no evidence to support" the idea that the majority of people imprisoned at Magdalene laundries were sex workers. The Irish Times reports that the reasons that women were sent to Magdalene laundries included court referrals for petty offenses, social service referrals, being poor and homeless, having physical or mental disabilities, and being rejected by foster parents.

Some women were also placed there by their own families "for reasons including socio-moral attitudes" and fear of scandals. Often, if a girl was being sexually abused by a family member, they'd be put in the Magdalene laundry as a way to put an end to the situation without addressing it. The Journal writes that the youngest person admitted into a laundry was eight, while the oldest was 89-years-old.

According to the Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee, state referrals during the 1930s and 1940s account for almost 25 percent of the women imprisoned. However, despite the fact that the State wasn't responsible for a majority of the admissions into the Magdalene laundries, the State "failed to protect and defend [the] individual liberty and human rights [of the women in Magdalene laundries], as they had a right to expect in a democratic State governed by the rule of law."

Conditions of the laundries

When a woman or girl was put into a Magdalene laundry, her name was changed, her hair was cut, and her clothes were replaced with a uniform. According to human rights lawyer Maeve O'Rourke, the institutions were often places of physical neglect, poor hygiene, little heat, "and lack of access to pain relieving medication." Justice for Magdalenes Research writes that they were rarely given any information about when or even if they were ever to be released.

Silence was enforced at almost all times, and "in many women's experiences, friendships were forbidden." Windows were either barred or unreachable and doors were often locked. Even when women did have friends and families outside of the Magdalene laundries, visits were discouraged and on the rare occasions that they did occur, they were supervised by the nuns.

Women and girls at the Magdalene laundries were forced to work throughout the day, and in addition to doing laundry they were often tasked with embroidering, sewing, or other manual labor. Some, like Mary Cavner, were sent to the laundries when they were children and received no education from the nuns while they were there. Instead, according to the BBC, Cavner "experienced long-term hunger while working into the night looking after babies, cleaning, working in the laundries and preparing meals for the nuns." And while the residents received no pay for their work, the Magdalene laundries "were run on a commercial, for-profit basis."

Widespread abuse at the laundries

Punishments at the Magdalene laundries were frequent and severe. If anyone refused to work, they were starved, humiliated, or put in solitary confinement, according to the Justice for Magdalenes Research. The Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee states that there were several recorded incidents of physical abuse and punishment, but many characterized their treatment as "mental cruelty." However, it appears to have been based on a particular Magdalene laundry. One woman recalls that on more than one occasion, "if you were talking you used to get a slap with a stick get on with work." The women at Magdalene laundries were overwhelmingly subject to verbal abuse and psychological abuse. One woman, who started to experience nocturnal enuresis while at the Magdalene laundry, said that "they pinned the [wet] sheet to me back and I was walking on the veranda with it."

The Journal writes that women and girls were forced to continue working no matter what. One woman remembered that when she had appendicitis and asked a Sister if she could go to bed, the Sister refused to let her leave her work.

According to Origins of the Magdalene Laundries, education was also withheld in order to "aid the promotion of magdalenism by keeping the inmates ignorant and therefore dependent on their keepers." Those who survived the Magdalene laundries consider this fact "as determining their 'loss of opportunity' in later life."

How many passed through the laundries

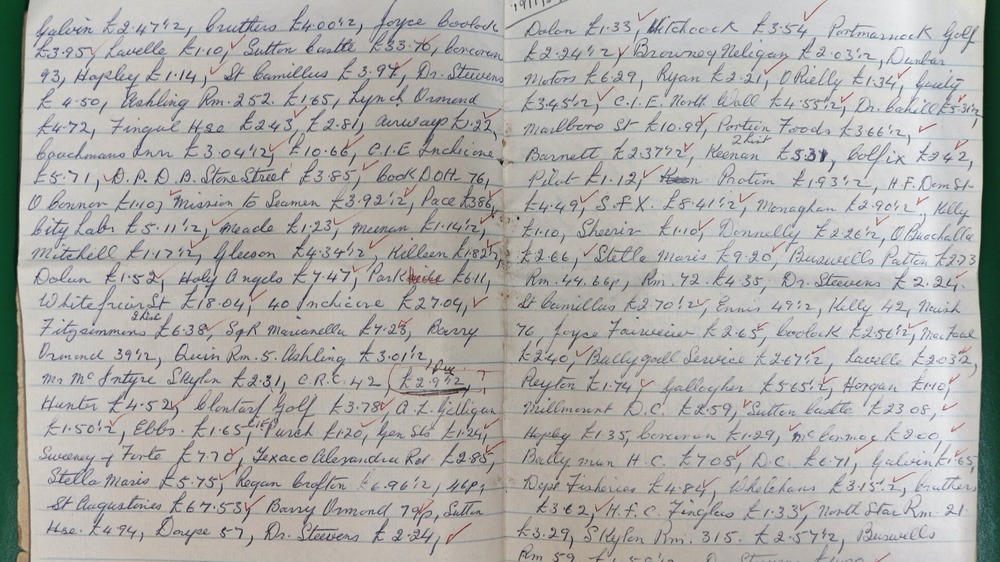

Since records of the imprisoned people weren't meticulously kept, although records of clients (pictured) were well kept, it's impossible to know exactly how many women and children passed through the Magdalene laundries. The Huffington Post reports that from 1765 to the late 1990s, roughly 30,000 women were imprisoned in Magdalene laundries. But according to the Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee over 10,000 women and children were put into the Magdalene laundries between 1922 and 1996 alone, and the Justice for Magdalenes Research notes that this figure is likely a "significant under-estimate." The Committee didn't include anyone who had been admitted before 1922 in their count, and "the Sisters of Mercy could not produce records for the Dun Laoghaire or Galway institutions." In "Ireland's Magdalene Laundries," Maeve O'Rourke and Dr. James M. Smith write that it's estimated that more than 10,000 women were put into Magdalene laundries before 1900, but since religious archives are incomplete "the final number is likely higher."

Women often tried to escape from the Magdalene laundries, but often they were captured by the Gardaí and simply transferred to another Magdalene laundry. If someone did end up being released, "it was invariably without warning, without money and with only the clothes she was wearing."

According to The Irish Post, some who survived escaped to Britain, lest "they'd be caught and incarcerated again." Many who entered the Magdalene laundries believed they were going to die there. And tragically, many did.

How many never made it out

Since it's unclear how many people were admitted into the Magdalene laundries, it's unclear how many never made it out. According to The Journal, Justice for Magdalenes Research has identified over 1,600 people who lost their lives in the Magdalene laundries. Comparatively, the Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee counted a little over 850 deaths, with ages ranging from 15 to 95.

Irish Times reports that numerous other mass graves of Magdalene women have also been discovered, such as the one at St Laurence's in Limerick, which contained the remains of 265 people, and the one at Bohermore in Galway, which contained the remains of 118 people. According to Justice for Magdalenes Research, "comparison of electoral registers against grave records at the Donnybrook location shows that over half of the women on electoral registers between 1954 and 1964 died in that institution."

And when women were pregnant or had a young child, they were sent to mother and baby homes, which collaborated with Magdalene laundries but were "distinctly separate," according to Vox. These places also have an unknown death count, as was demonstrated when a mass grave of infants was found in Tuam, County Galway. According to The Guardian, the remains of almost 800 infants were discovered at the former Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home, ranging from 35 weeks to three years of age. However, it's important to note that it's difficult to know whether or not the children died due to negligence.

Illegal adoptions from Magdalene laundries

If the nuns at Magdalene laundries were managing to keep children alive, they would sometimes steal and export them. According to Irish Central, upwards of 2,000 children were "illegally exported" to the United States and adopted. The Journal reports that between 1950 and 1952, at least 330 children were adopted by Americans.

According to Adoption Land, the nuns regarded the pregnant women at the Magdalene laundries with malice. One woman, Maria, recounts her experience after being raped and being sent to Bessborough for becoming pregnant. When she asked a Sister for help during labor, the Sister responded, "Ah, Marie. You should have thought of the consequences before getting yourself in this mess. Tell me, was the two minutes of pleasure worth all this?"

Sometimes, birth certificates would even be altered to remove the existence of the birth mother. According to The New York Times, in over 100 instances "babies born to unmarried mothers were adopted and their adoptive parents' names were written on their birth certificates, instead of the name of the birth mother." And these cases only involve a single adoption agency. Now, though, those children are adults and are "demanding justice for their birth parents and an apology from the Irish government who they say were totally complicit in the cover-up of what went on."

The role of the state

The Irish State bears a great deal of responsibility for the Magdalene laundries. Not only were "more than a quarter of referrals made or facilitated by the State," according to Irish Times, but often these referrals were made for crimes such as failing to purchase a ticket.

"Ireland's Magdalene Laundries" writes that the State used Magdalene laundries as an alternative to prisons and youth detention centers, and even paid to have women and girls detained after they were convicted. The Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee also found that the State had contracts with the Magdalene laundries for their laundry services, which amounted to almost 20 percent of the Magdalene laundries' sales. And since the laundries were considered workplaces, they were subject to the Factories Act. This meant that they were being inspected by the state just as commercial laundries were, which means that the State was more than aware of the situation inside the Magdalene laundries.

As a result, it appears that the government "knowingly failing to regulate [Magdalene laundries] to prevent arbitrary detention, slavery or servitude, forced labor, psychological or physical torture or ill-treatment, denial of education to children, or many other forms of abuse." And according to Vox, during the mid-1960s, the state started paying "capitation grants for each woman" sent to a Magdalene laundry. Meanwhile, mother and baby homes were regulated by the State and received stipends.

The last Magdalene laundry

It wasn't until 1993 that the abuses of the Magdalene laundries started to be uncovered. According to Irish Central, when the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity sold part of their convent in 1993, developers found the mass grave of the laundry, which "led survivors to come forward and speak of their own experiences." And three years later, on September 25th, 1996, Our Lady of Charity on Sean McDermott Street, the last Magdalene laundry, finally shut down.

According to Dublin InQuirer, before the laundry of the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity closed, it saw its fair share of escapes, and a young couple named Betty and Tony Dunleavy, who lived nearby at the time, even helped two women break out and sheltered them while the nuns hunted. But sometimes, in an attempt to help they'd inadvertently harm. Once, after giving a woman in the Magdalene laundry some food, Tony Dunleavy was chastised for feeding the women and the woman's hair was "cut as punishment for her transgression."

As of 2021, the building of the last Magdalene laundry remains, and although there were plans to turn it into a memorial for the Magdalene laundries, many "survivors complained it would be another Dublin-centric move, when most victims were hidden away down the country," according to the Irish Independent.

Campaigning for an apology

Initially, the Irish government refused to acknowledge or apologize for the abuse that occurred at the Magdalene laundries because they insisted that these were events that happened in private institutions, which the government wasn't responsible for. And this remained the case until 2013, when the Inter-departmental Committee released their report about their 18-month investigation into Magdalene laundries.

According to "Ireland's Magdalene laundries," although the report didn't conclude that the State was wholly responsible for the abuse that occurred at the Magdalene laundries, it "revealed significant new information regarding the State's interactions with the institutions" and discovered that the State was definitely involved and complicit in the institution of Magdalene laundries.

The Journal reports that on February 13th, 2013, Taoiseach Enda Kenny of Ireland made a formal apology to Magdalene survivors, admitting that "As a society, for many years we failed you." For many, this was seen as an incredibly significant step, since "it lifted the silence that shrouded the experiences of girls and women in these institutions since the foundation of the State." Unfortunately, as O'Rourke and Smith note, "bearing in mind the Constitutional rights violations, trauma and loss of opportunity suffered, the redress recommended was minimal."

An apology to the survivors

Although the government acknowledged their involvement in the Magdalene laundries, the compensation they offered the survivors seemed to suggest otherwise. The redress offered by the government was significantly characterized as a "'gift,' rather than as of right or as compensation for wrongdoing by the State," according to "Ireland's Magdalene Laundries."

The government offered the survivor several benefits, including a lump sum payment, but in order to receive the benefits, it was required for them to "sign away all of their legal rights against the State upon accepting benefits under the scheme. It is highly questionable whether this waiver is compatible with international human rights law or, indeed, the Constitution."

According to The Journal, in 2018, the compensation scheme was reworked to include "women who worked in the Magdalene laundries of 12 religious institutions but were resident in one of 14 adjoining institutions," since they were initially ineligible for compensation. As a result of this amendment, over 100 more women became eligible for compensation due to their time in the Magdalene laundries. The Sisters that ran An Grianán and High Park, the Magdalene laundries, continue to deny the fact that they made the women and girls do laundry work after the 1980s.