Operation Pedro Pan: Cuba's Mass Exodus Of Children Explained

For two years in the 1960s, Operation Pedro Pan, also known as Operation Peter Pan, resulted in thousands of Cuban children being relocated to the United States. With the help of the Catholic Welfare Bureau and the U.S. State Department, Cuban parents were able to send their children off in the hopes of finding a better future. And since this implied a rejection of communism, the United States was eager to accept children, and later their families, making the overall operation "the largest and longest refugee resettlement initiative in U.S. history."

It seems that as long as there's a political agenda to be exploited, the United States government is more than happy to accommodate refugees. It's especially striking to note that the idea that parents are trying to give their children a better life, once used to justify facilitating the separation of children from their parents in Cuba, is now disparaged by right-wingers when talking about contemporary immigration from Latin and South America. And even when accepting refugees during Operation Pedro Pan, families still ended up being separated, and they weren't always reunited. This is Operation Pedro Pan — Cuba's mass exodus of children explained.

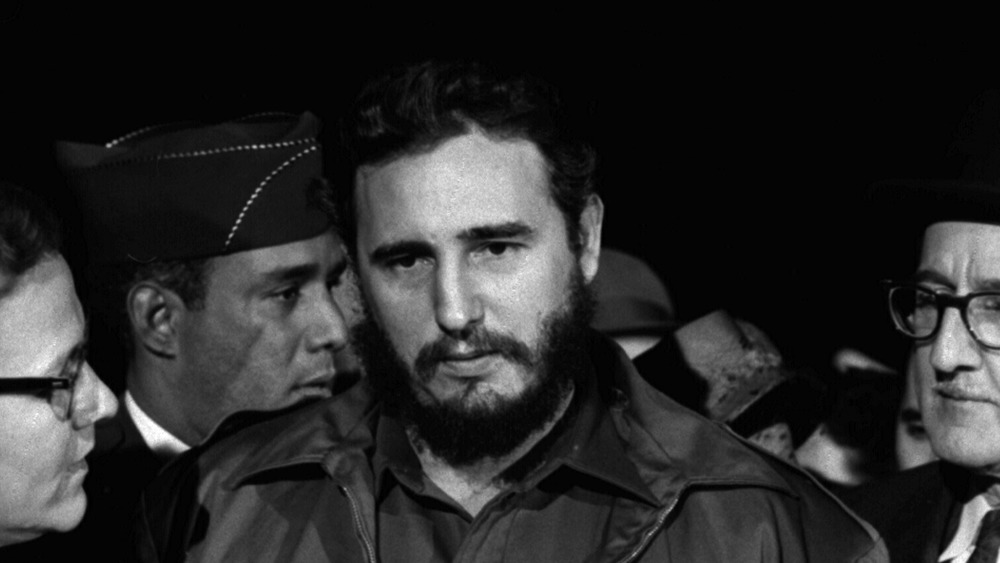

Batista falls

Fulgencio Batista's military dictatorship, which was backed by the United States, lasted from 1952 to 1959, until he was ousted by Fidel Castro in the Cuban Revolution. At the time that Batista was ousted, Cuba's literacy rate was 77% overall, though in rural areas it was closer to 57%, according to The Atlantic.

Literacy and education became two big initiatives for Castro's government. However, according to National Geographic, for some people the education strategy was considered indoctrination, especially after it was reported that Cuba's minister of education said, "the teacher has an unavoidable obligation to transmit revolutionary thinking to students."

And according to the University of Miami, after rumors started circulating that Castro's government was going to "separate parent and child so the children could be properly taken care of by the government with minimal parental contact," some parents became eager to send their children out of Cuba. Though according to The New York Times, these "fears never materialized."

Many of these parents with these fears had already "sent their children to private Roman Catholic schools, so they turned to the Catholic Welfare Bureau for help." Some children, like Armando Vizcaino and Antonio Garcia, ended up being sent to the United States because their parents were worried about their counterrevolutionary activities.

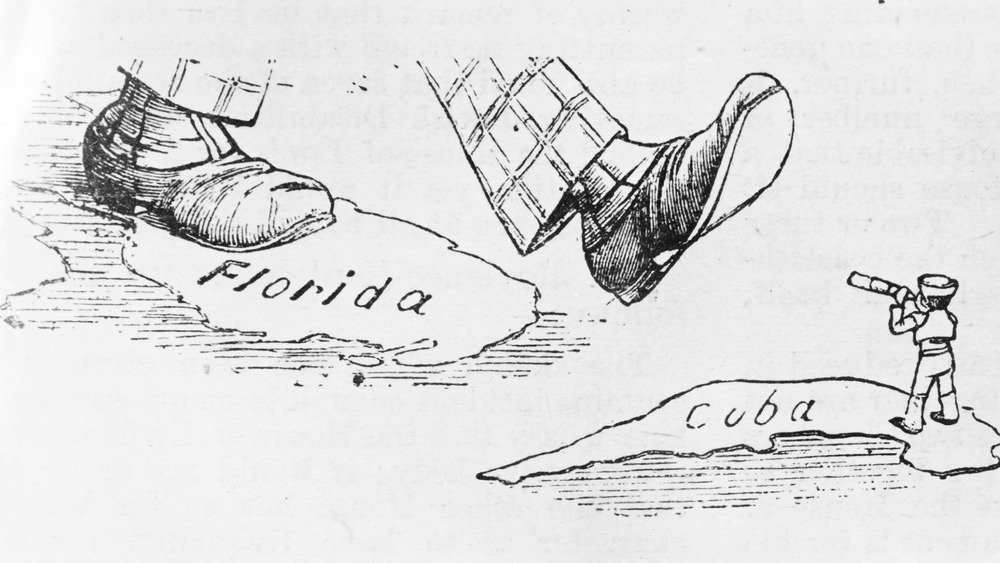

Fidel Castro and the United States

When Fidel Castro deposed Fulgencio Batista and sought to shake off America's imperialism, Cuba's relationship with the United States was already tenuous at best. But once Castro started developing relations with the Soviet Union and, according to the Council on Foreign Relations, nationalized all foreign assets in Cuba, the United States pushed back hard.

In response, TIME Magazine reports that on Oct. 19, 1960, President Dwight D. Eisenhower imposed a trade embargo on Cuba that covered every export except for medicine and some food. In 1962, President John F. Kennedy expanded it to cover imports as well, and the following year travel was restricted as well.

In 1961, the Kennedy administration also attempted a takeover of Cuba, "executing a plan developed and approved by the Eisenhower administration." However, the Cuban military were able to defeat the "1,400 CIA-sponsored Cuban exiles" in three days, in the event known as the Bay of Pigs invasion. Undeterred, the United States spent the next several decades trying to assassinate Castro no less than some 600 times. And according to Reuters, the U.S. trade embargo cost Cuba over $130 billion over the course of 60 years.

Father Bryan O. Walsh gets involved

Operation Pedro Pan was the brainchild of Monsignor Bryan O. Walsh, director of the Catholic Welfare Bureau, who after spending a summer in Puerto Rico studying Spanish had come back to find that the Catholic Welfare Bureau in Miami was concerned with the recent influx of Cuban refugees in Miami. According to AL DÍA, Walsh realized that some parents were sending their children to live with relatives in the United States, but that not all the relatives could afford to support the newly arrived children.

University of Miami writes that in December 1960, Walsh met James Baker, a headmaster of an American school in Havana. Baker had come to the United States hoping to create a school to provide education and housing to Cuban refugee children, and when he learned that the Catholic Welfare Bureau had a similar plan, they joined forces.

"Operation Pedro Pan was born as Mr. Baker agreed he would get the children out of Cuba while Monsignor Walsh would secure their care in the United States." It was named after Pedro Menéndez, a Cuban boy Walsh met who was in the very predicament Walsh was now determined to address.

Who was Pedro Menéndez?

In November 1960, Father Bryan Walsh met Pedro Menéndez, a 15-year-old boy who'd been in the United States for almost one month. According to the University of Miami, Menéndez "had been passed around from family member to family member without any security or stability in sight [after being] sent to the United States by his parents, alone, under the expectation relatives or friends would care for him."

Since few relatives in Miami were financially secure, much less able to take on another child, Walsh saw Menéndez as emblematic of an oncoming refugee crisis. According to Walsh himself, "the incident alerted me and reminded me that every refugee migration has unaccompanied minors, teenagers usually who are separated from their families with maybe younger children."

On Dec. 14, 1960, James Baker sent a letter to Walsh with a list of the first group of children to be brought to the United States. He also added that since "there is a rumor here that no children will be allowed to leave Cuba after January 1, we are therefore rushing this work as much as possible in order to get out as many children as possible during the holidays."

According to Penn Political Review, Walsh was later able to secure funding from the federal government as well, "being the first private agency in the United States to do so for child care."

How many children were transported?

Initially, the Catholic Welfare Bureau planned on transporting 200 children. But according to Penn Political Review, they were soon claiming that "the demand from Cuban parents to send their children to the United States was higher than expected," and over the course of two years, almost 14,000 Cuban children were moved to the United States.

AL DÍA reports that "of the 14,048 minors who left Cuba alone in those 23 months, 6,584 were placed with family friends or relatives already established in the United States, [while] 7,464 remained under the protection of the Cuban Children's Program of the Catholic Bureau and other Protestant and Hebrew agencies." There were numerous camps and "transitional shelters," reports The Washington Post, which "were at best inhospitable and at worst uninhabitable."

Although some siblings were kept together, others were separated. And "on at least one occasion, children were redirected to facilities that were not properly certified by child welfare agencies. There were also numerous allegations of physical and sexual abuse."

Where did the children go?

Some, like 16-year-old Armando Vizcaino, stayed with Father Bryan Walsh himself. Others were put with family members who were already living in the United States. But nearly 7,500 other children were placed in foster care homes across "35 states with the help of 95 different child welfare agencies," says Penn Political Review, though some report as many as 48 states and territories. According to the University of Colorado Boulder, roughly 85% of the children were between ages 12 and 18, though there were some as young as 6 years old, and there's even "evidence of parentless toddlers in transit."

And not all who had relatives in the United States ended up with relatives while they waited to be reunited with their parents. When Guilleromo, Roberto and Juan Vidal got to Miami, instead of meeting relatives, "they were rounded up and put on a plane to Chicago and then to Pueblo, Colorado, where they spent nearly three years waiting for their parents to come."

Visa waivers on demand

Initially, the system of getting children to the United States was designed to require as little interaction with the embassy as possible for Operation Pedro Pan, also known as the Cuban Children's Program. Tickets were purchased by the Catholic Welfare Bureau, and student visas would be acquired through the embassy. According to Cuban Refugee Children, by Bryan O. Walsh, it was believed "advisable to have a separate money order made out for each child as the sending of a large money order for several tickets at one time would draw attention at the Banco Nacional that tickets were not being paid by the parents of the children."

But according to The New York Times, when the United States Embassy in Havana was closed by the beginning of 1961, Walsh "turned to the State Department, which gave him blanket authority to issue visa waivers to children 6 to 16. Older children had to undergo security clearances before they could travel." Walsh sent visa waivers to Cuba, and once the forms were filled out, the children traveled to the United States. "When the organizers in Cuba ran out of forms, they falsified them."

AL DÍA writes that Pan Am, National, and KLM airlines were used, and sometimes there were as many as two Pan Am flights direct from Havana to Miami every day.

How long were children separated for?

While some children were reunited with their family within six months to a year, for some children it took years before they could see their parents again. For Armando Vizcaino, although he was reunited with his parents after two years, his father died shortly after, according to National Geographic.

Others, like Jose Azel, never saw their parents again. NPR reports that Azel was sent to the United States by his father after his mother died in 1961, and Azel got involved in "underground activities." There was a belief that they would be reunited, but Azel's father died in Cuba in the mid-1970s.

According to Smithsonian Insider, many "left thinking they would eventually return to the island, but never did." Penn Political Review reports that at least 10% of children never saw their parents again. Those who weren't reunited with parents or family members ended up staying in the foster care system until they were 18 years old.

The Catholic Church was also reportedly very strict about making the children learn English and exposing them to American culture, and only allowed English to be spoken in the church orphanages.

Prominent Pedro Pan participants

Many children who were part of Operation Pedro Pan went on to become prominent figures in American culture. Artist Ana Mendieta was 12 years old when she and her 15-year-old sister were sent to Iowa from Cuba in 1960. According to the Guggenheim Museum, their father had joined an anti-Castro counter-revolutionary force and would later be imprisoned for 18 years as a political prisoner "for his involvement in the Bay of Pigs invasion."

Due to a power of attorney signed by the parents, the sisters weren't separated, and during their first two years, Mendieta and her sister, Raquelin, moved eight times to various foster homes and institutions. Mendieta wouldn't see her mother again until 1966 or her father until 1979.

Mendieta was also "among the first Cubans to return to the country in 1980," according to Artsy.

NPR also reports that former Florida Sen. Mel Martinez was also part of Operation Pedro Pan as a child, as was musician Willy Chirino. However, for many people who were children in Operation Pedro Pan, the experience of being separated from their families had lasting impact.

The impact of child separation

In the end, children were never taken by the government in the way that parents feared they would be. And yet, The New York Times reports that "many Pedro Pan children say they would do what their parents did, given the same circumstances." Others meanwhile believe that while their parents decision was the right one, they would "never do the same thing to their own children," writes The Washington Post.

However, Yvonne Conde, who was separated from her parents when she was 10, is wary of people claiming that the program was entirely positive, especially since the participants people know about are often ones coming forward to show their success stories, and not everyone has a success story.

For others, the impact of separation manifests in adulthood. "Raquelin Mendieta cannot cry. Maria de los Angeles Torres cannot send her daughters alone in a plane anywhere. And Antonio Garcia, married for 31 years, cannot stand to be apart from his wife for even one night."

McClatchy News reports that at least one former Pedro Pan refugee alleges that Father Bryan Walsh abused him while he was under his care in 1964 at a camp in Opa-locka. According to Repeating Islands, "People should be aware that there was mental, sexual, and physical abuse; and the same priests told us that if we spoke out, we would be sent back to Cuba and that we would bring shame on our families."

Commercial flights come to an end

After the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, commercial flights between Cuba and the United States were suspended. According to AL DÍA, with the suspension of flight, Operation Pedro Pan came to an end, since for the next three years travel from Cuba had to occur through a third country, Spain and Mexico.

The Washington Post writes that this made getting an exit visa more difficult for parents, since there were now additional waiting periods and requirements. According to the Department of Defense, Fidel Castro announced on Sept. 28, 1965, that anyone who wanted to leave Cuba by boat to go to the United States was welcome to do so. The port stayed open for a little less than two months, during which time almost 3,000 Cubans immigrated to the United States.

According to "Cuban-American Cuba Visits," by Susan Eckstein and Lorena Barberia, during this time the State Department also helped almost 5,000 Cubans immigrate in what was known as "Operation Sealift." And by December, President Lyndon Johnson decided to work with Castro on family unification, which led to the creation of the Freedom Flights.

Freedom Flights

The Freedom Flights lasted from 1965 to 1973 and were responsible for reuniting a majority of children with their parents. However, according to The Washington Post, "entering the United States did not guarantee parents instant reclamation of their child." Local authorities inspected families before returning children to their parents, and in several instances "one or both parents had landed in the United States but were not immediately reunited with their children because the Catholic Welfare Bureau did not know they were in the country."

Often, children had lost their fluency in Spanish as well, which made communication with their parents difficult. Other times, children were hesitant to rejoin their parents after having been separated for so long. According to Migration Policy, Freedom Flights also transported people the United States described as "refugees from communism." In total 260,600 Cubans were brought to the United States on the Freedom Flights, making it "the largest and longest refugee resettlement initiative in U.S. history."

The Antonio Maceo Brigade

In 1977, 55 Cuban children who'd traveled to the United States as part of Operation Pedro Pan went back to Cuba. Known as "Los Cincuenta y Cinco Hermanos," "Antonio Maceo Brigade," or the "Maceitos," this group of young Cubans sought "to become a post-revolution bridge between Cuba and its exile," writes The Washington Post.

On Dec. 21, 1977, the Antonio Maceo Brigade made a visit to Cuba, though there had been particular stipulations that none of them had previously been involved in counterrevolutionary activity. Although they were welcomed in Cuba, they were called traitors in the United States. And two years later, one of the founders of the Brigade, Carlos Muniz Varela, was assassinated in Puerto Rico.

Upon returning, the members of the brigade came away with different impressions of Cuba, once more shattering the notion that all exiles are of the same mind.

During the 1970s, some Cubans, including Ana Mendieta, became involved in El Diálogo, an initiative to increase communication between Cuban emigrants and Cuba. According to MIT Press Journals, family reunification were considered an essential part of the conversation, and Artsy writes that these dialogues "led to the legalization of family reunification visits, which began in 1979 under President Jimmy Carter."

Family reunification visits

Under President Jimmy Carter, the United States lifted its travel ban on Cuba and also participated in talks that led to the release of over 3,500 political prisoners in Cuba. According to MIT Press Journals, during this time family reunification visits were also permitted, which resulted in almost 150,000 Cuban-Americans visiting Cuba between 1979 and 1982.

Family reunification visits appear to have continued under both the Reagan and Bush administrations, seemingly because they were seen to be "destabilizing to the Castro regime in that they dispel propaganda about the United States fed by the Castro government to the Cuban people," according to the Committee Hearing on The Role of Cuba in International Terrorism and Subversion.

But in 1994, the Clinton Administration changed the policy to only allow émigrés to visit Cuba only once per year. Tampa Bay Times writes that this was in an attempt to dissuade people from bringing money back to relatives in Cuba, and the administration also curbed the amount that people were allowed to send to Cuba via transfers.