How The Sears Catalog Helped Fight Jim Crow Racism

A century before Amazon upended the retail industry, there was the Sears catalog. If Amazon takes advantage of technology like the internet and delivery trucks, Sears Roebuck and Company took advantage of the technology of their time: expanding railroad lines and the postal system, which was enhanced, says RFD TV, after the Rural Free Delivery Act was passed in 1893, enabling people living in rural areas to have mail picked up and delivered from personal mailboxes rather than having to go into town to post mail.

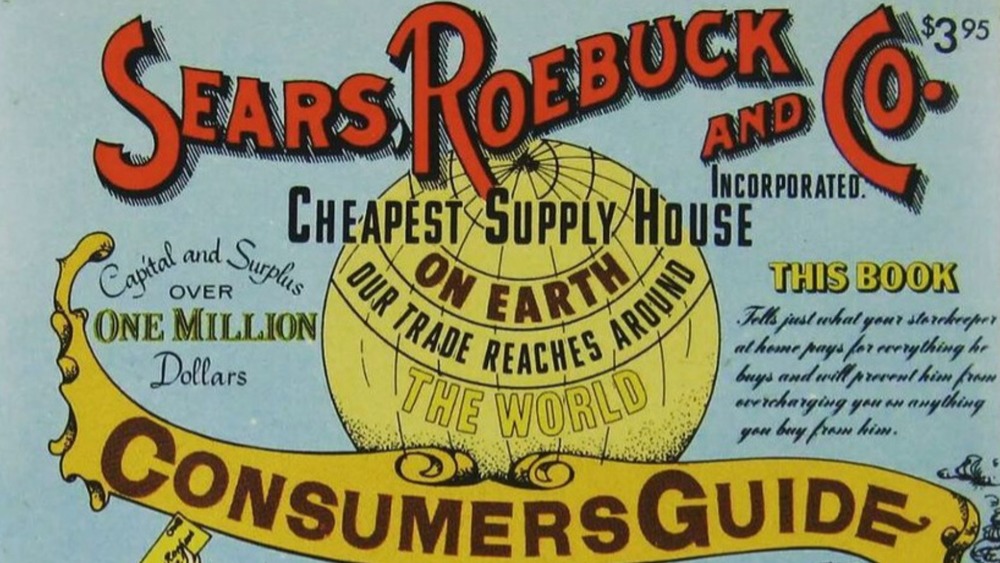

In 1894, the Sears Catalog started answering a variety of needs and wants through what the company advertised as the "Cheapest Supply House on Earth," and those items and savings were available to "the world," according to Sears Archives. While that may sound like the usual sales pitch today, the offer to sell the same wares to anyone with the same convenience factors was new in the late 1800s. That was especially true in the Black community. Even though slavery had been abolished by then, Black Americans found themselves subjugated to another caste system, that of the Jim Crow era.

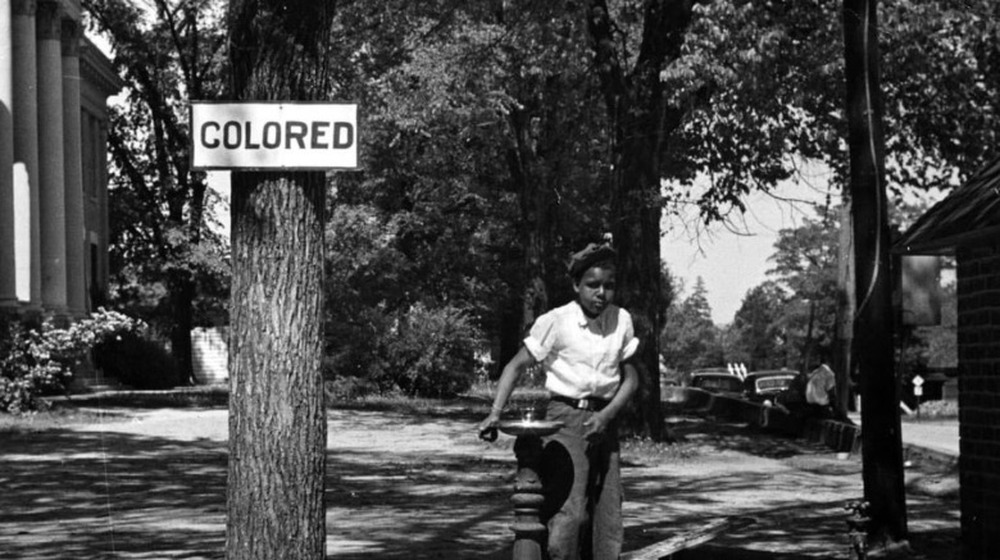

According to the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University, from 1877 to the mid 1960s African Americans were subjected to a set of laws and etiquette that were imposed by whites in an effort to keep the races separate, to keep Blacks oppressed, and to ensure the continuity of white supremacy. That even spilled over to shopping experiences. That is, until the Sears Catalog became a great equalizer.

Sears did not discriminate against customers based on their skin color

The Chicago Times reported that during the Jim Crow era, Black customers had to not only wait for all the whites to get served first, but were also not allowed to buy items the store owners deemed too good for them. But access to items via mail order meant there was no distinction on race.

According to a twitter thread by Louis Hyman, History Professor and the Director of the Institute for Work Place Studies in New York City, "The catalog undid the power of the storekeeper, and by extension the landlord. Black families could buy without asking permission. Without waiting. Without being watched. With national (cheap) prices!"

Hyman wrote that there was a backlash from the white community, who viewed Sears as taking power — and revenue — from the local white store owners. They burned Sears catalogs in bonfires and spread the rumor that Richard Sears, the store's co-founder, was Black, in an effort to dissuade whites from buying from the catalog. Sears published a photo of himself proving otherwise. Sears seemingly had no interest in cutting out Black customers. According to Sears Archives, in 1903 he added a line of wigs specifically for African Americans.

"So as we think about Sears today," Hyman wrote, "let's think about how retail is not just about buying things, but part of a larger system of power. Every act of power contains the opportunity, and the means, for resistance."