The Secret History Of The American Presidency

You don't even have to be American to hear a lot about the American presidency. Most of it centers around the man currently holding the office, but the office itself is pretty fascinating, too. While it's nice to think that the people in charge of running things know what's going on and all have their master's degrees in Adulting, it turns out that the whole thing is pretty much being made up as we go along.

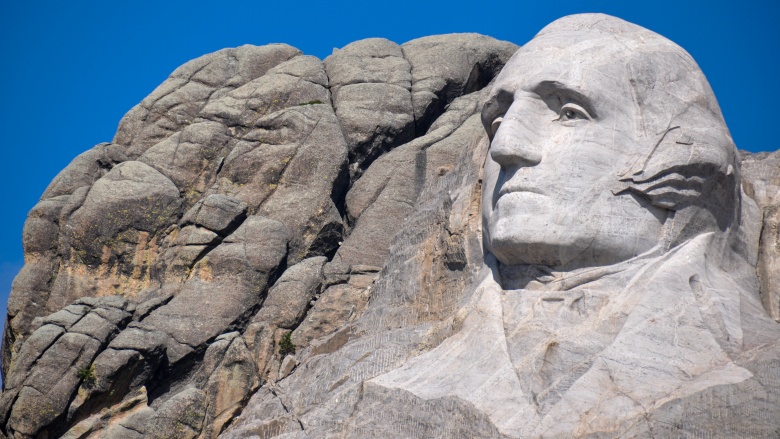

There were eight presidents before George Washington

It's one of those things that you learn early on in your elementary school career, but like a lot of things your teachers tell you, it's technically wrong. While George Washington was the first president under a country united by the Constitution, he wasn't the first president of the actual country by a long shot.

Before the Constitution, and after that whole thing with the British, there were the Articles of Confederation. What that did was basically create a country out of those original 13 colonies, and it also set in place some rules for keeping things from going sideways. It established Congress as a ruling body, and it also put someone at the head of the whole thing—a President.

The new country was still a bit squirrelly about giving one man too much power, so this president was mostly responsible for organization, keeping meetings on track, signing official documents, and generally keeping everything heading in the right direction. John Hanson was the first to hold the office, starting with the ratification of the Articles in 1781 and ending his term in 1782. He oversaw things like the formation of the US Post Office and currency, but most of these early presidents didn't do much besides watch.

Succeeding presidents served for a year each, too, and included Elias Boudinot (oversaw the Treaty of Paris and fought for Native American rights), Thomas Mifflin (ratified the Treaty of Paris), Richard Henry Lee (later became one of the most vocal opponents of the Constitution), John Hancock (the signature guy), Nathaniel Gorham (supported the future Constitution), Arthur St. Clair (went on to govern the Northwest Territory), and Cyrus Griffin (founded the base of our judicial system).

If you want to go even farther back, there were a whole list of people who served as presidents even before the Articles of Confederation. We won't give you the long list of names, as what we already have is enough to show how wrong your teachers really were.

The woman who assumed the presidency for 17 months

Woodrow Wilson was elected as the 28th president in 1913, and declared war on Germany in 1917. By the summer of 1918, he was undergoing treatment for developing health problems — at the time, it was all kept incredibly quiet. He spent some of 1919 campaigning for support for the Treaty of Versailles, but collapsed in October when he was incapacitated by a stroke. For the rest of his presidency he went into seclusion, and the public had no idea what was going on. It was only with the release of personal documents kept by his physician that more and more started to come out about what went on behind closed doors.

It seems like a huge oversight but, at the time, there was absolutely nothing in place that would automatically hand the duties of the president over to the Vice President if something should happen. It's in the law books now, but at the time, Wilson's stroke left the country without a president. His VP, Thomas R. Marshall, was so terrified he'd be assassinated, he refused to take on the mantle.

So who helmed the country? Edith Wilson, the First Lady. According to her rather modest biography, most of her duties centered around caring for her bedridden husband. But historians have dug a little deeper to find that Congress's complaints about a "petticoat presidency" wasn't a dig at him at all, and instead a reference to just how much influence she had. Newspapers made remarks about what a capable president she was, and even though she never called herself a president, she effectively ran the office from behind closed doors for 17 months.

Even after the Wilsons' term ended, there was still nothing put in place for the succession of the VP in case of emergency. That didn't happen until 1965, with the 25th amendment.

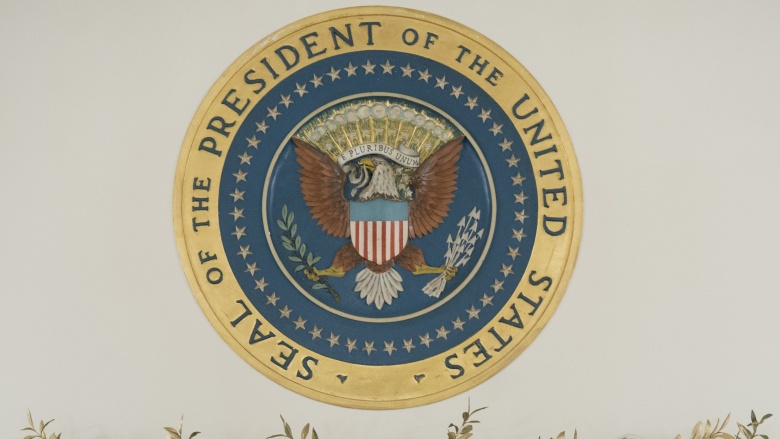

What makes the Presidential Seal, well, presidential?

The image of an eagle grasping both arrows and an olive branch is one of the most recognizable symbols in the world, but it's not always the Presidential Seal. It's only actually, really official when it has the words "Seal of the President of the United States" — otherwise, it's just the Presidential Coat-of-Arms. (Add that to the list of things you never knew you needed to know.) Also, take away the stars and then you have the Great Seal of the United States, which means the presidential version is actually more ornate than the nation's. That's not a bad deal.

It's gone through a few changes over the years, and it was first designed (roughly) in 1850 by Millard Fillmore. He's the one that sketched the first rough draft, and it was actually drawn by a professional seal engraver named Edward Stabler. His image had much older roots, as the eagle-arrow-olive branch motif dates back to 1782. Today, the eagle is looking toward the olive branch he's holding, but it wasn't always that way. It was Truman that changed the seal to have the eagle looking in the direction of peace, rather than war, a powerful statement that came on the heels of World War II.

Early presidents were little more than figureheads

The idea of an American president is pretty much a given today, but in the early days, when the memories of a British monarchy were still painfully fresh, the idea of a president was considered by some to be one small step away from a dictator. Even Patrick Henry described the idea as a "squint toward monarchy," and he wasn't alone in his thinking. Even as others called for a king, most were hesitant to put too much power in the hands of one person.

The original presidents, therefore, didn't have much power, even though they still remain symbols of the young country. The office was so small and had so little to do that in 1800, it moved all its documents and directives to Washington, DC in seven small cases. There was no real party divisions, either, and that allowed early presidents to set some major precedents.

It was Washington that established the idea of things like appointing department heads as assistants, rather than rivals, and put himself firmly at the head of things like foreign policy. By the time Jefferson was president, he was still trying to find his footing, but was also noted to be one of the last presidents who could court members of Congress with things like dinner dates, reaching out to extend his power that way. After him, getting the corner table in the city's fanciest restaurant was a little more difficult, but we know that it still happens. We watch Netflix.

Presidential power remained firmly in check for a surprisingly long time

With a few notable exceptions—like Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln—the presidents that sat at the head of the country through the 19th century were still relatively powerless. Jackson set a few major precedents, like establishing the idea of the confidentiality of the office and his position as the head of the entire country, regardless of party affiliations. We're honestly not surprised that he was among the most badass presidents of that century. He did, after all, fight in and walk away from at least 103 duels, including one where he was shot in the chest. Plugging the hole and taking careful aim, he shot and killed his opponent. We wouldn't mess with him any day of the week.

For all that, though, he wasn't much of a policy-maker, and some of the things he did put in place fell apart when his successors took office. It's a hugely different picture than the one we see today, and the power shift didn't really happen until a few landmark events. Teddy Roosevelt was the first to use the press to his advantage, recruiting the first press secretary and setting himself up as the colorful character devoted to his country ... and if he happened to oppose Congress in a few things, he made sure he had the upper hand.

FDR was handed a huge amount of power in hopes of getting the country through the Great Depression, and by the end of his reign, the world was on the brink of another major war. Presidential power continued to expand, but it wasn't until Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis that the presidency really started to look like what it does today.

Contrary to popular belief, there's no set-in-stone, tried-and-true formula for the presidency. It's constantly changing, and that's a really weird thing.

The secret letters each President leaves their successor

There's been a lot of jokes about Joe Biden's plans for when he leaves the White House, but it's been a long and, until recently, pretty secretive tradition that each outgoing president leaves a note for his successor. But writer and TV personality Brad Meltzer found out quite a bit when he emailed former President George HW Bush, and asked him if this tradition had anything to do with sharing top secret information about the Culper Ring, a Revolutionary War-era spy ring he suspected was still around.

Bush responded with a copy of the letter he had left for Bill Clinton, and after spending days trying to break what he thought was a code, Meltzer realized he had something completely different sitting on his computer screen. The letter didn't include anything about politics or policies, and was instead a reminder of the very human nature of these larger-than-life figures.

Most of the letters have remained a secret, but we do know that Ronald Reagan left HW a pad of stationery that said, "Don't let the turkeys get you down," and an accompanying note. Clinton mentioned the tradition in his autobiography, yet the contents of the letters remain secret. We're still holding out for information on the Culper Ring.

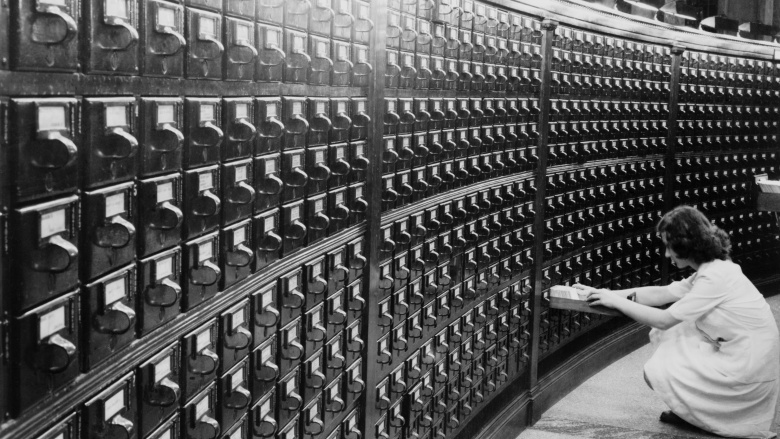

The "real" Presidents' Book of Secrets

The idea of a super-secret book that contains all the classified information a president needs to know is a pretty cool idea, but we see something wrong with it right away. It would have to be huge, and it turns out that's basically why one doesn't exist.

Well, not technically.

According to the Library of Congress, they get requests for the book all the time, which is hugely optimistic on the part of the requesters. Who knows, maybe it's someone's first day on the job. There is a sort of Book of Secrets, and that's in the National Archives and Records Administration. They're the ones that keep tens of thousands of pages of classified information and documents on investigations that are still open, and as you might expect, there's a lot of security that goes into maintaining the secrecy of what's in those documents.

They also say that the classification system usually assigned to the Book of Secrets (at least, the one popularized by the Nicolas Cage movie) gives it the number XY234786, but there's no such XY classification even listed in the Library of Congress. That makes us wonder if it's just something they're not telling us about.

The VP was originally "without employment"

Today, the VP takes on some pretty major tasks but originally, they weren't nearly as important. In fact, they weren't important at all, and were only appointed to serve as a sort of backup president, just in case. Early on, they weren't even considered a part of the executive branch of the government. They were legislative, and they were given only a single duty: acting president of the Senate. Sounds important, right? They actually only had one job, and that was to cast a deciding vote if everything else was tied. It's almost as if they were given this solely to keep them from complaining that they were bored.

It wasn't until 1832, when Andrew Jackson (who might honestly be our favorite president ever) put Martin van Buren in a position where he could act as an actual adviser, that the VP title started to mean something. It wasn't until much, much later, that the VP was awarded any kind of real responsibilities, and the first to assume any was Jimmy Carter's veep, Walter Mondale.

The vice presidency has always been something of a weird position, and at least one president made it a point to choose a VP so bad, it made his own position more secure. Richard Nixon's choice of Spiro Agnew was something of an insurance policy that he wouldn't be removed from office amid scandal. Of course, Agnew wound up being so bad he was forced to resign, and we all know how that wound up.

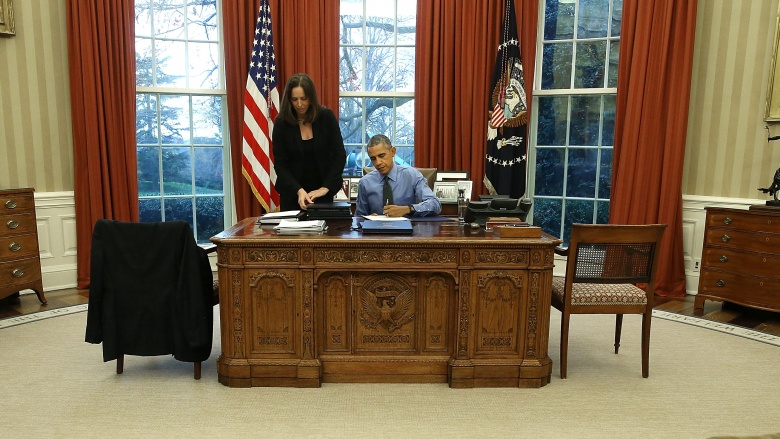

The Oval Office desk has a weirdly complicated history

We all know that the incoming First Family redecorates the White House, and another highly visible change is sometimes the desk that sits in the Oval Office. While George H.W. Bush's was only used for his one term, there have been some others that carry some pretty funky history with them.

The first of them all was the Roosevelt Desk, built in 1903 for Teddy Roosevelt. Seven presidents have chosen this particular desk as their own, almost destroyed in a fire before being used by Harry S. Truman for his presidency. Now, it's the VP's desk, and all the VPs who have used it have signed the top drawer. The massive Wilson Desk was the chosen desk of Richard Nixon, wired with microphones and playing a major part in the Watergate scandal.

But the coolest is definitely the Resolute Desk. That's the one that Obama, Clinton, W. Bush, Reagan, and Carter all used, first put there by Jackie Kennedy for her husband's use. Before that, it had been a centerpiece in the White House study, specially adapted by FDR to include a secret panel that could be opened and used to hide his legs. Even by then it had been around for decades, originally given to the White House in 1879 as a gift from Queen Victoria.

The Resolute Desk gets its name from the HMS Resolute, a British naval ship that was stranded and abandoned in the Arctic. It made its way south and was rescued by an American crew, who fixed it up and sent it back to Britain as a token of goodwill. After a few decades, it was ultimately scrapped, but the queen ordered the desk to be made from the ship's timbers and presented to America as another gesture of goodwill. That officially makes it the coolest upcycling project in the world.

Bohemian Grove: the super-secret, elite, presidential summer camp

Just what goes on every summer at the so-called Bohemian Grove is one of the country's last great secrets. It's been infiltrated a few times, but we've only really been given some tantalizing, sometimes-scandalous glimpses into what going on there. A lot of that information came in 2009, when Vanity Fair writer Alex Shoumatoff made it past security and into the camp that's the summer retreat of around 2,500 of America's richest, most powerful men.

While there's still a lot of secrecy, we do know that Bohemian Grove has some inarguable ties to the presidency. In 1967, Richard Nixon gave a talk there that marked the beginning of his campaign. Some photos clearly show Nixon and future president Ronald Reagan at a table in the Grove, and reportedly, every GOP president since at least Eisenhower has made the pilgrimage to the elite summer camp every year. While we know that business talk is supposedly forbidden, we do know that's a rule that gets broken a lot. Bohemian Grove was the place the Manhattan Project was formally planned, after all.

Those who have worked there suggest there's nothing truly sinister going on there, and that the days of planning projects like the atomic bomb are long gone. Now it's more about a shared camaraderie, they say, but it's still impossible to tell just how many deals have been made because of what's gone on there. Good luck getting there to find out, either — in 1989, the waiting list for an invite was 33 years long, and we can't even imagine how long it is today.

The presidents and Freemasonry

Who doesn't love a good conspiracy theory? Because seriously, they can explain a lot. There's a ton of conspiracy theories out there about the Freemasons and their plans for world domination, so it makes sense that, if they wanted to put their people into positions of power, they'd get them elected as presidents.

As far as we know, only 14 presidents were also Masons: Washington, Monroe, Jackson, Polk, Buchanan, Johnson, Garfield, McKinley, Teddy Roosevelt, Taft, Harding, FDR, Truman and Ford. That's less than a third, and while it's still a significant number, you'd still think that if they were as all-powerful and power-hungry as they're reputed to be, they would have managed to do better than that.

There are some very real connections between the US government and Freemasonry, though, including the design of the Washington Monument. It's modeled after the idea of the Lighthouse at Alexandria, and there's plenty of portraits done of the Masonic presidents in their full regalia. There's also links to Masonry in things like the design of the Capitol building and the imagery on American currency, but just how far the Mason's reach goes remains up for debate. And conspiracy theories.