This Was The Most Powerful First Lady In American History

Generally speaking, first ladies aren't given much attention. Sure, they're married to the president of the United States of America and they live in the White House. They're also expected to take on all manner of social and charitable duties, which are arguably important and certainly noble. They might even have some soft power, given that they can pretty easily get the president's attention and perhaps deliver their own opinions on matters of state, at least unofficially. Yet, very few people indeed would argue that spouses of U.S. presidents have any real power at all.

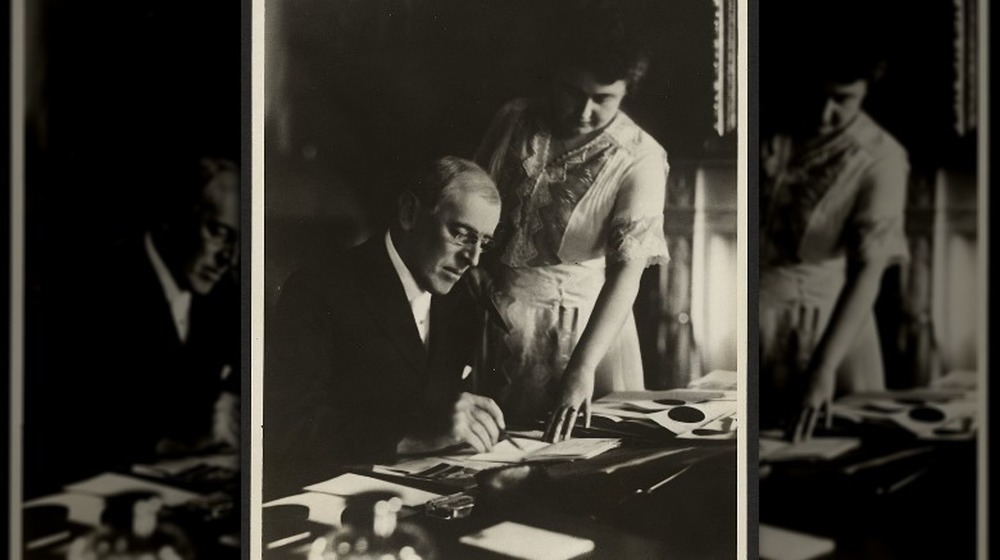

That is, except for Edith Wilson. On the surface, Edith, the wife of 28th U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, seemed much like any other first lady. She took on charitable ventures, attended social engagements and, once World War I broke out, set an example of thriftiness and bravery for the rest of America. Then, in the aftermath of World War I, her husband had a stroke. From that 1919 health crisis to the end of his presidency in 1921, President Wilson was severely incapacitated. Acting quickly, his wife soon began managing his meetings, what documents he saw, and may have even made some serious governmental decisions, though Edith herself demurred and said she was only protecting her beloved Woodrow.

Since that extraordinary period, historians have debated the nature of Edith Wilson's role in the White House. Regardless of the details, however, it's clear that she was quite possibly the most powerful First Lady in American history.

The future Edith Wilson grew up in obscurity

Though Edith Bolling and her family claimed descent from Southern aristocracy, you wouldn't have necessarily known that upon her birth in 1872. According to History, she really did have a pretty illustrious list of ancestors, including direct descent from 17th century Powhatan woman Pocahontas on her father's side and, through her mother's lineage, connections to Thomas Jefferson and Martha Washington. In another era, perhaps, Edith Bolling would have grown up to become a high-class Southern debutante who enjoyed a wide range of perks and social connections related to her station.

Then, the American Civil War happened. Things finally got rough for Southerners who had previously benefited from the old, inhumane system and Edith's grandfather lost control of the family plantation. After the sale of their family estate, Edith's father worked as a lawyer supporting his increasingly large family. Even then, the Bollings lived above a store in Wytheville, Va., hardly the palatial estate of a kind enjoyed by other first ladies. Edith, born well after the end of the war but still solidly in the midst of Reconstruction, may have heard tales of her family's past, but would have only had to look around her to see that her present was markedly different.

Edith didn't get much of a formal education

Though she eventually gained a reputation as an intelligent and energetic woman, young Edith didn't receive much in the way of a formal education. As First Ladies reports, this was a bit odd. Her sisters attended school like any other children of the time, so we can't properly blame prevailing cultural attitudes or even necessarily the individual quirks of the Bolling family. Instead, it appears that Edith, along with her family, decided that she wasn't necessarily suited to more formalized education.

Edith, however, was not left to run wild. Her paternal grandmother was bedridden after a spinal injury and Edith was tasked with taking care of her. In turn, her grandmother educated the younger girl in the basics of math, literacy, and traditional homemaking skills like sewing. Edith also learned a kind of pidgin French from her grandmother that was mixed with English. And, while it wasn't a formal skill, Edith soon grew to make strong and quick judgments like her grandmother, a personality trait that arguably helped her catch the eye of a president and eventually led to her historic, if obscured, role within the White House.

Eventually, Biography says, Edith did enroll in school, though it wasn't a wild success. She reportedly dropped out of Martha Washington College because it was too cold, though it's easy enough to wonder if she simply wasn't inclined to the structured environment of higher education and finishing schools.

She married a wealthy jewelry magnate in 1896

Though a childhood in West Virginia meant that Edith Bolling's beginnings were rather obscure, she still managed to travel in such a way that brought her into some pretty powerful circles. Yet, as the White House notes, that travel was a long time coming. Edith didn't leave her hometown until she was already 12-years-old.

When she was a young woman, Edith traveled to Washington, D.C. in order to visit one of her married sisters. While there, she connected with a wealthy jewelry magnate named Norman Galt. They connected so well that the pair married in 1896. Considering Galt's successful business, Edith seemed to have it made, at least financially. Norman and Edith were married for 12 years, during which time Edith became a comfortable society wife, though the two never had children. She was also, as Biography reports, barred from the true society life, as her money was gained through icky business interests and not what was thought to be more "pure" inherited, familial wealth.

Norman died suddenly in 1908, leaving Edith in charge of the family business. She chose a manager to undertake the nitty-gritty of running the jewelry firm instead of doing it herself, leaving Edith free to move on with her personal and social life in the wake of her husband's death.

Edith caught Woodrow Wilson's eye in 1915

The widowed Edith Galt still went out and had fun, sticking to a social life that would lead her to a pretty fateful encounter in the early 20th century White House. According to Biography, she went out with a friend, Altrude Gordon, who was herself dating the official White House doctor. Edith and Altrude eventually became close with Helen Bones, President Woodrow Wilson's cousin, who was living with the president as a companion while Woodrow was mourning the death of his first wife. Edith, Altrude, and Helen went out for a hike and returned, reportedly quite muddy, to the White House. As the story goes, Woodrow was captivated by the energetic Edith and pushed to get to know her better.

The pair embarked on a whirlwind courtship that, in some circles, skirted scandal. Presidential Studies Quarterly notes that the letters exchanged between the two were pretty romantic. They might have also breached some rules of state, as Woodrow shared official documents directly with Edith, both apparently to impress her and get her opinion. Edith certainly enjoyed it. "Much as I love your delicious love letters," she wrote to her beau, "I believe I enjoy even more the ones in which you tell me [...] of what you are working on [...] for then I feel I am sharing your work and being taken into partnership as it were." The pair eventually married on December 18, 1915, less than a year after their initial meeting.

In public, Edith was a traditional First Lady but didn't relish the role

Like many first ladies before and after her, Edith Wilson wasn't especially enamored of the traditional requirements of the role. She was thrust into the role of rather quickly, says the Miller Center, and apparently didn't much enjoy the traditional social demands of being the president's wife. To that end, she hired a secretary to manage her social engagements.

When World War I happened, she seemed more interested in setting a thrifty, nontraditional example for other Americans. This meant that the fluffier aspects of first ladyship, like the annual Easter Egg Roll on the White House lawn and what may have seemed like endless dinners and teas held in the mansion, ceased for a while. Instead, Edith set rationing standards for the dinner table like "meatless Mondays" and allowed sheep to graze on the White House lawn instead of hiring expensive gardeners.

Then, there were duties more directly related to the war. Some of what Edith Wilson did was pretty well in line with the motherly role afforded to many first ladies, like knitting and sewing goods for American soldiers. Others were a little more high profile, like volunteering with the Red Cross in public places in the busy train hub of Union Station.

Behind closed doors, Edith Wilson was a serious presidential advisor

Even before his stroke, Woodrow Wilson often showed state documents to his wife and asked her opinion. Edith Wilson also decoded some military messages. Some officials complained that Edith had too much influence over the president.

As the Miller Center reports, some were already worried about Edith's presence, given that she married Woodrow Wilson about six months after the death of his first wife, Ellen Axson Wilson. President Wilson's advisors had tried to keep the union from happening, worrying about scandal after the quick marriage, but Edith became Mrs. Wilson anyway. They likely got more worried once it became clear that the president was seeking her opinion on pretty high-level matters of state. Edith also sought to oust those who critiqued her union with Woodrow.

After World War I finally became an issue to the Americans and the United States entered the war, she even helped to decode highly classified military messages. According to the National First Ladies' Library, President Wilson even shared the key to his private desk drawer with her, shared wartime codes, and took her advice on how to deal with his fellow politicians. Edith was even sometimes able to sit in on meetings between Woodrow and top-level officials.

Edith Wilson wasn't much of a friend to the womens' rights movement

Though Edith Wilson proved to be a surprisingly powerful person after she became the first lady, her views did not always extend that same influence to other women. Both she and President Woodrow Wilson were skeptical of the women's suffrage movement that sought to give all American women the right to vote. Early on in his political life, as Political Science Quarterly relates, Woodrow even wrote that he got a "chilled, scandalized feeling that always overcomes me when I see and hear women speak in public."

As per Britannica, the president once ordered that suffragists protesting in front of the White House should be arrested. Edith subsequently referred to the women as "those devils in the workhouse." Though Woodrow eventually softened his stance to the point where he supported an amendment granting women the right to vote, there's no evidence that Edith felt the same way.

Edith Wilson could still be progressive in other respects, however. She earned the first driver's license issued to a woman in Washington, D.C., as the Chicago Tribune reports, and could be seen driving about in an electric car. Clearly, she also didn't necessarily think that women — or at least herself — should be totally shut out of governmental matters. Given that Edith happily and freely gave her opinions to her husband, who himself sought out her advice, she could hardly argue against it.

Woodrow Wilson suffered a fateful stroke after World War I

Though World War I was officially over by 1918, the stress and anxiety caused by the conflict would affect Edith and Woodrow Wilson for years to come. PBS reports that, in the immediate aftermath of the war, Woodrow spent months overseas negotiating the Treaty of Versailles. Even though it effectively marked the end of hostilities, Congress met it with resistance and gave Woodrow what sounds like a pretty hard time over the matter.

When President Woodrow Wilson returned to the United States to begin promoting the League of Nations, an attempt at creating an international organization of countries in the wake of the war, things got even worse. Woodrow took on a nationwide speaking tour to promote the League of Nations, taking along a retinue that included Edith on the three-and-a-half-week venture.

It was Edith who found the president in a dire state after a September 1919 engagement in Pueblo, Colorado. His face was drooping, his muscles were twitching, and he complained of an intense headache. It appears that this was a "mini stroke" that precipitated an even bigger one that occurred in October 1919 in the White House. Again, Edith found him, got Woodrow back into bed, and called the White House chief usher, telling him that "the president is very sick."

To get to the post-stroke President Wilson, you had to go through Edith

This second stroke was demonstrably bad. As PBS reports, President Woodrow Wilson's doctor, Cary T. Grayson, upon seeing him after the October 1919 event, was horrified. "My God, the president is paralyzed," he said.

A paralyzed president was no good for governing a nation. Yet, Edith Wilson and a small circle of officials were determined to keep the truth of Woodrow Wilson's condition a secret. Ultimately, this meant that, to get to the president, you had to go through Edith Wilson. According to Biography, she carefully screened visitors and documents before they made it in front of the president and crafted press releases stating that he was only overworked and needed a bit of a rest. And, when Woodrow did have in-person meetings, Edith was often there and helping her husband to hide the true nature and extent of what had happened to him.

By February 1920, however, news was starting to trickle out. Rumors flew that the president was ill, insane, or both and that someone else was running the nation in his stead. But, as the Chicago Tribune reports, in an age without social media and nearly instantaneous reporting, it was hard to get the exact truth out of the White House. Even the vice president didn't really know what was going on with his own running mate until more than three weeks after Woodrow Wilson's health crisis.

Edith Wilson had a complicated political role in the White House

Later in life Edith Wilson downplayed her power in the White House after her husband's stroke. She often said that she was only acting in her husband's interest, trying to keep him healthy and stress-free — after all, as she might have rightfully argued, it was stress that got them into this mess in the first place — rather than trying to take the reins of power. As quoted in Presidential Studies Quarterly, an older Edith wrote that: "I myself, never made a single decision regarding the disposition of public affairs. The only decision that was mine was what was important and what was not, and the very important decision of when to present matters to my husband."

It is true that Edith Wilson didn't exactly become a "secret president." According to the National First Ladies' Library, she often let the Cabinet deal with political issues, for instance. Yet, neither is it totally fair to dismiss her. Edith wasn't above taking more of a leading role when she had a stake in political issues, whether it was something of a bigger interest or even a petty issue. Once, she refused to let the government accept a diplomat's credentials until he dismissed someone that had made jokes at her expense. Moreover, the person controlling the flow of information to a president is very powerful, indeed, no matter how much they might try to convince you otherwise.

After Woodrow Wilson's death, Edith set about securing his reputation

Though he eventually recovered somewhat from his stroke, Woodrow Wilson never fully regained his strength. Neither did his project of kickstarting the League of Nations. And, as History reports, the whole situation had more or less become public knowledge by the early months of 1920, though Edith Wilson's role in the White House after her husband's stroke appears to have been poorly understood.

The National First Ladies' Library reports that Edith might have inadvertently had a hand in the failed League of Nations proposal, as she could have advised Woodrow to accept a compromise to get the legislation passed. Yet, it's hard to pin the blame on a single person, much less someone who was operating in an informal capacity like Edith was. Either way, she continued to screen documents and visitors for her husband after they left presidential life. She was even reportedly considered as a vice presidential candidate in 1928, four years after Woodrow Wilson died. That never happened, but she enjoyed acclaim and recognition nonetheless.

In her 1938 autobiography, My Memoir, Edith Wilson attempted to establish an image as a loving wife to President Wilson, and especially as someone who didn't meddle in governmental affairs. However, later historians found significant omissions and changes in her accounts. She supported John F. Kennedy's campaign and lived to attend his inauguration in 1961, which would be her last public appearance. She died later that year of a respiratory infection.