What You Didn't Know About Serial Killer Amelia Dyer

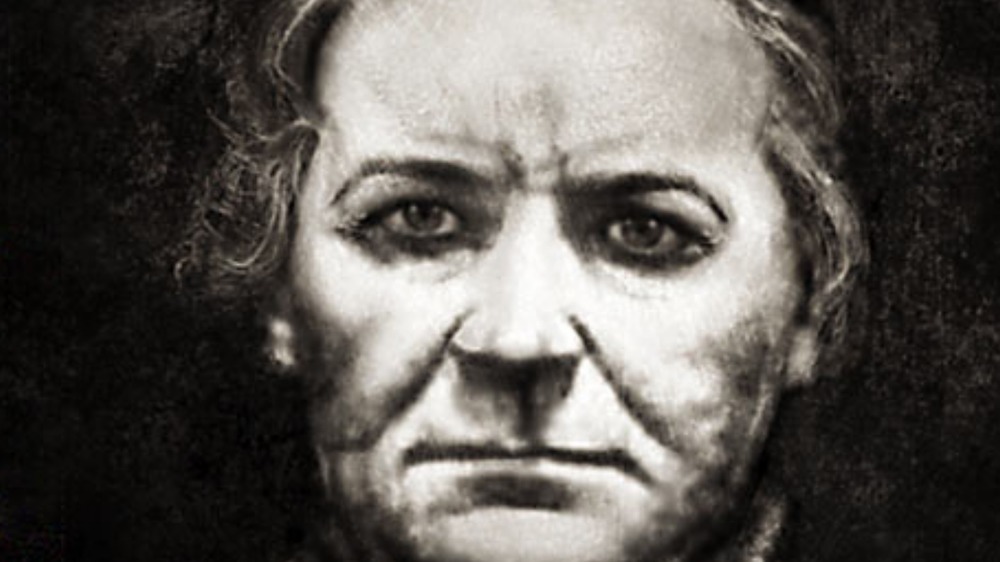

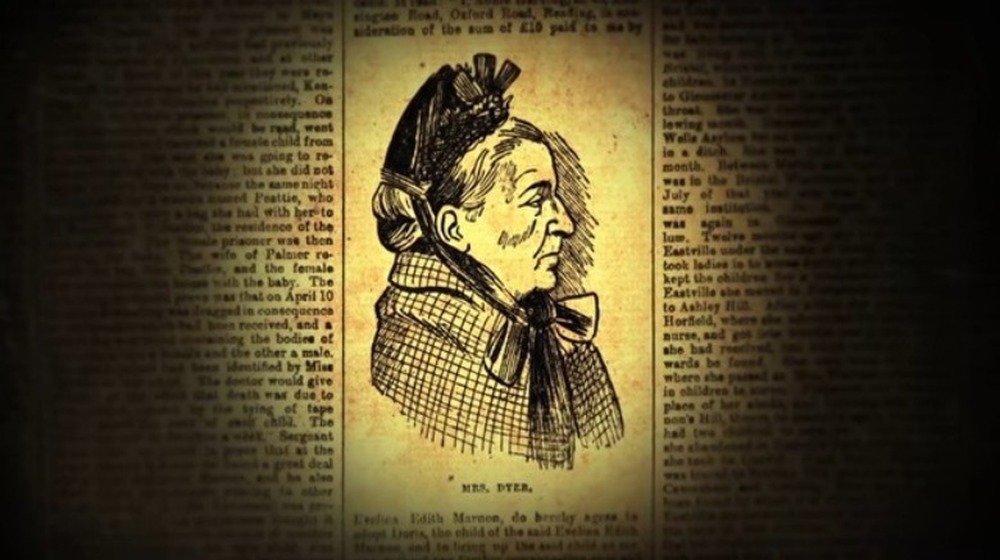

Female serial killers are relatively few and far between, which perhaps makes their crimes all the more fascinating and disturbing. It's particularly creepy when the crimes are carried out against babies, and that was exactly the case with Amelia Dyer, a "baby farmer" in 19th century England who is thought to have murdered over 300 babies during her reign of terror.

"Baby farming" in and of itself sounds disturbing, but it's simply "a pejorative [term] that came into use only in the latter half of the nineteenth century" that "referred to a person, usually a woman, who took in and cared for the children of other women," per The Ultimate History Project. Due to the era's lack of safe, dependable birth control as well as the stigma of having children out of wedlock, some women placed their children with paid caregivers. Things were further complicated by England's Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, which forbade parishes from giving unwed mothers any aid unless the women entered a workhouse, which was "a bleak existence for mother and child alike." Some women opted to work in domestic service as maids instead, but this often meant they had to live in their employer's home and couldn't bring their child, forcing them to leave their babies in foster care with "baby farmers." Many children left in these situations died of malnourishment and neglect.

Baby farming was a way of life in Victorian England

Amelia Dyer was born in 1837 in a small village in Brighton, England, as reported by the BBC. She had a hard childhood, during which she was responsible for the care of her mentally ill mother. As an adult she married, had a daughter, and became a nurse. Her role as a "baby farmer" began in 1869; she learned of the opportunity to make some money from another nurse. She'd advertise in newspapers that she was a married couple (despite being separated from her husband) with a "good country home" wishing to adopt a child for which she charged "a small premium."

Dyer traveled from her homes in Bristol and Reading to locales as distant as Liverpool and Plymouth, charging between £10-£80 to take in babies, which was the equivalent of £1,000-£8,000 pounds today (about $1,400-$11,000). Writer Angela Buckley, author of Amelia Dyer and the Baby Farm Murders, said the babies' parents wouldn't have known that Dyer planned to kill their children, explaining, "They believed that they were sending their child to a happy home." As History Collection notes, "in already overcrowded cities, it was relatively easy for Amelia Dyer to operate her baby farming business with little suspicion. Because poverty was prevalent in England, many people went hungry. Infant mortality rates were very high."

Godfrey's Cordial was used to keep babies quiet

As soon as Dyer had taken responsibility for a baby, the child's days were numbered. History Collection further reports that Dyer "immediately began the process of killing [the baby] by starvation," drugging infants with an over-the-counter medicine called Godfrey's Cordial, also known as "Mother's Friend" for its sedative effect on children. As the topic was a mixture of "syrup and opium," it likely contributed to the babies' deaths, as well as keeping them quiet as they starved. The use of Godfrey's Cordial and similar narcotic syrups to keep babies quiet was common during this time. A 1999 academic article, "Opium and Infant Mortality," available on Victorian Web, reported that in Manchester, England, "five out of six working-class families used it habitually."

After a baby perished, Dyer would call in a doctor to declare the child dead and take the body away. Occasionally doctors would become suspicious of the fact that so many children died while on Dyer's watch, at which point she would pull up stakes and move on to another town or "[have] a mental breakdown and [enter] into an asylum."

Amelia Dyer was caught, but it didn't last

In 1879, a doctor grew suspicious enough to contact the authorities, which resulted in Dyer being convicted of neglect and serving six months of hard labor, writes History Collection, which seems like an awfully lenient punishment for someone responsible for the deaths of a slew of babies. She continued acquiring babies after her term was up, and from 1880 forward she skipped the starving and drugging elements of her crimes and simply started strangling the children and disposing of their bodies herself. One of her tools was white dressmakers' tape, later admitting "that she liked 'to watch them with the tape around their neck' as they gasped for air." She would then wrap up the bodies and bury them, or weigh them down with rocks and throw them into the Thames River.

This practice finally led to the discovery of Dyer's murderous practices. As reported by the BBC, on March 30, 1896, someone pulled a package, weighed down with a rock, out of the Thames in Brighton. Upon opening the box, authorities discovered the body of infant Helena Fry, with white tape wrapped around her neck and tied under her ear.

Victorian forensic evidence and a sting operation

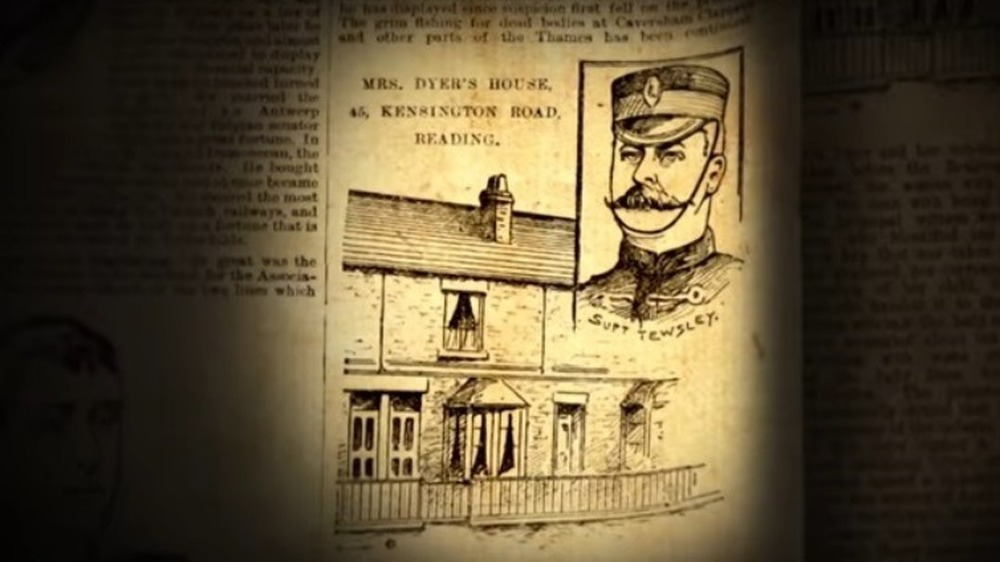

Detective Constable James Beattie Anderson examined the body and the package in which it was found, according to the BBC, and found "a Midland Railway stamp dated October 24 1895 and was marked Bristol Temple Meads" as well as "the smudged name and address of a Mrs Thomas of 26 Piggott's Road, Caversham — Dyer's married name and former address." Per the History Collection, authorities performed a sting operation in which they placed a fake ad in a newspaper seeking a loving couple to take in a newborn. Dyer left her home, thinking she was going to meet with a new client, on April 3, 1896, but was instead approached by four police officers.

They searched her home, which reportedly stank of rotting flesh and contained enough evidence such as "letters, advertisements, telegrams, and opium" to arrest Dyer and charge her with murder. The BBC also notes that white tape identical to that found around Helena Fry's neck was also found in Dyer's home.

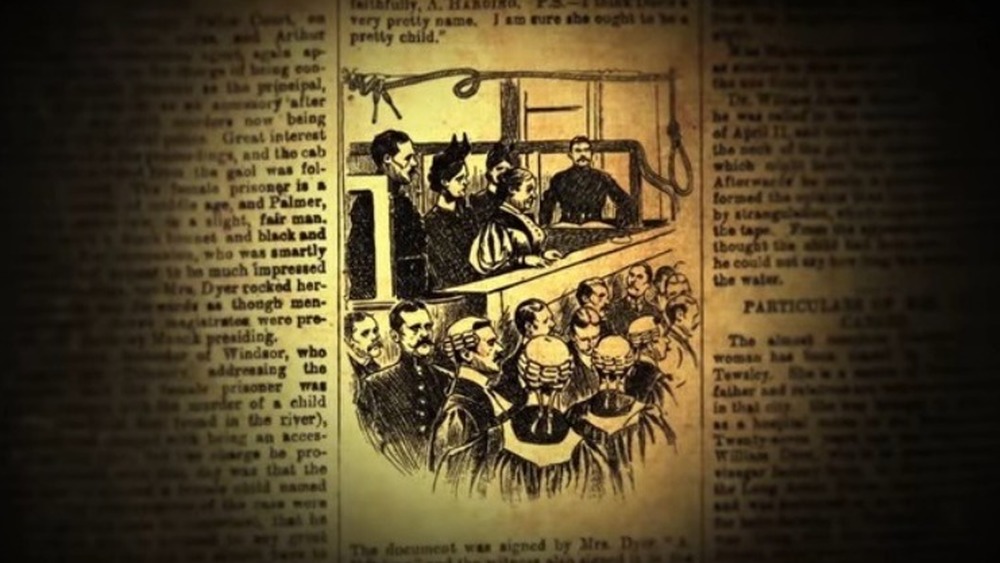

Her trial at the Old Bailey in London began on May 22, 1896.

Amelia Dyer unsuccessfully pleaded insanity

Following the discovery of Helena Fry's body in the Thames River, authorities dredged both the Thames and the River Kennet and found six more corpses of missing babies, all with the same white tape around their necks, relates the BBC. Dyer pleaded insanity, as she had spent time in mental asylums in the past, but prosecutors argued that these past breakdowns were merely ploys to throw off suspicion. Witnesses reported seeing Dyer take in as many as six babies at a time –author Angela Buckley estimated that she was probably responsible for the deaths of hundreds of babies, considering she spent 30 years "baby farming."

Lecturer Charlotte Beyer of the University of Gloucester noted that the trial "brought to light the otherwise repressed but widespread practice of baby farming, and revealed the horrors and inhumanity of this trade." The National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children had just been established, and the Dyer case highlighted its work and necessity.

According to the History Collection, Amelia Dyer was placed on trial for the murder of three children. She was found guilty on May 22,1896; the jury took less than five minutes to decide her fate. She spent three weeks writing her "last and true confession," admitting to her crimes, and was hanged at Newgate Prison on June 10, 1896. While 14 murders were linked directly to her, it's estimated that she really killed over 300 of the babies entrusted into her care.