Details You Didn't Know About Serial Killer Amy Archer-Gilligan

Arsenic and Old Lace is one of the all-time classic theater productions, performed everywhere from the Broadway stage to the smallest of community theaters. Playwright Joseph Kesselring wrote the black comedy in 1939. It premiered in 1941 and went on to have a whopping 1,444 performances on Broadway, per the Internet Broadway Database, as well as a concurrent 1,337 performances in London's West End at the Strand Theatre, per Theatricalia. A successful and critically acclaimed movie adaptation directly by Frank Capra and starring Cary Grant followed in 1944 — the movie is number 30 on the American Film Institute's list of America's 100 funniest movies of all time, and is the method by which most people were introduced to elderly, genteel sisters Abby and Martha Brewster, who are actually serial killers who take in old men as boarders and then immediately poison them to death to "end their suffering."

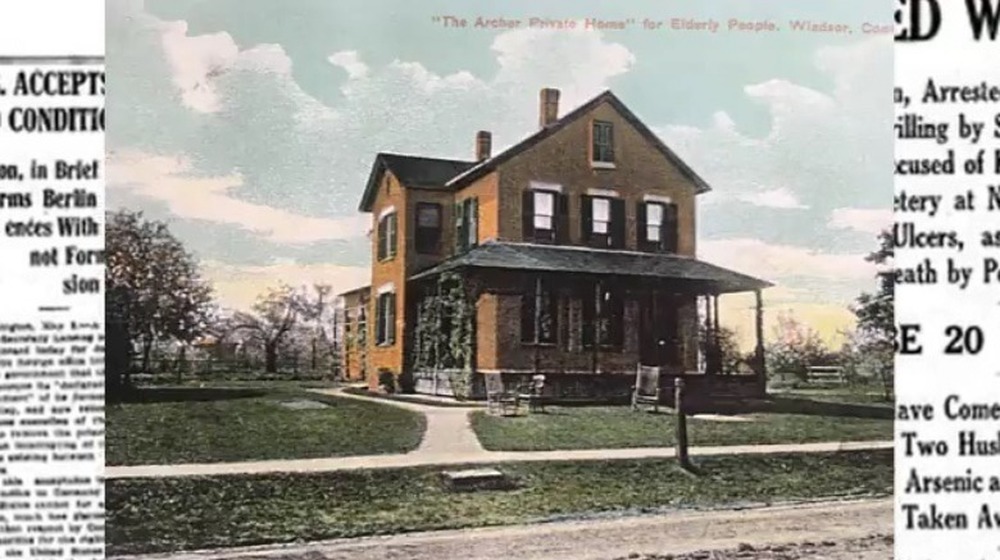

It's all played for madcap laughs, but the real-life story that inspired Joseph Kesselring is, naturally, much more disturbing. The Brewster sisters are very loosely based on Amy Archer-Gilligan, who ran a nursing home in Windsor, Connecticut — The Archer Home for Aged People and Chronic Invalids — and is thought to have poisoned between 20 and 100 people left in her care.

The Archers pioneered nursing homes as elder care

Per Connecticut History, Amy Duggan was born in 1873 and married her first husband, James Archer, in 1896. Five years later, John Seymour hired them as caretakers of his home in Newington, Connecticut. After Seymour died in 1904, the couple stayed in the house and made their living taking in elderly boarders. In 1907, they sold the house and moved to Windsor to open the Archer Home for Aged People. Ozy notes that "nursing homes were a relatively new type of facility in the early 20th century ... so government oversight was essentially nonexistent." In 1909, a family sued the Archers for "lack of care given" to a relative living at the Archer home. They settled for $5,000, "a tidy sum back in those days."

James Archer died of kidney failure in 1910; according to Ozy, he left his widow "with a 12-year-old daughter to support and a surprise bill for back taxes." Amy Archer was by then "a fixture in the local community" who went so far as to donate a stained-glass window to a local church. Apparently it was at this time that fellow Windsor residents noticed that Amy "seemed to purchase unnecessarily large quantities of arsenic to control a rat problem she claimed to have at the nursing home." She married her second husband, Michael Gilligan, in 1913; he died just three months later.

A widow again after just three months

As reported by the Windsor Historical Society, Michael Gilligan had been a "vigorous widower" when he and Amy Archer married in late 1913. On his February 1914 death certificate (he died at age 56), "valvular heart disease" [was] the primary cause of death, with a secondary cause: acute bilious attack." Furthermore, much to the chagrin of his family, he had left his wife his entire estate, which was worth over $4,000.

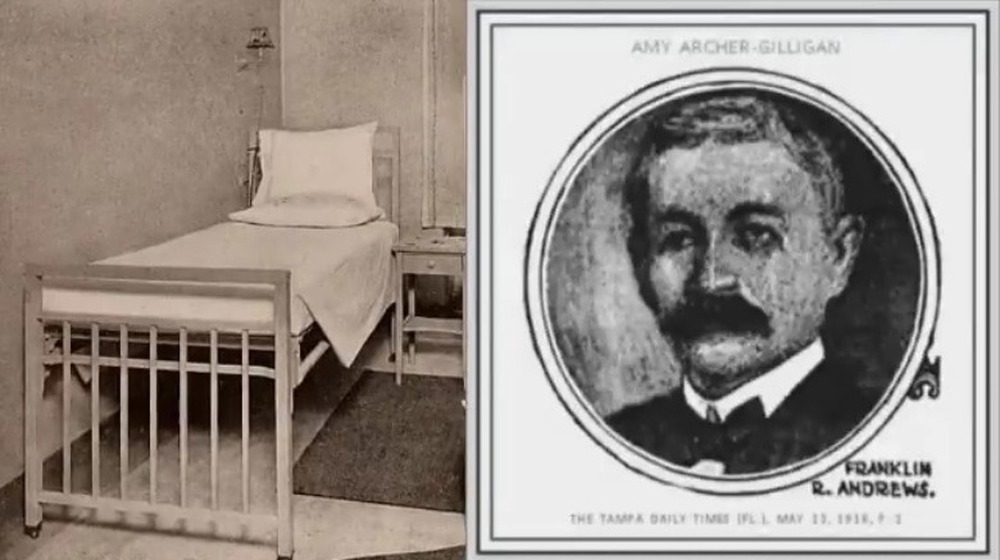

More suspicion came Mrs. Archer-Gilligan's way when one of her seemingly healthy residents, a 60-year-old man named Franklin Andrews, who often did odd jobs around the Archer Home, suddenly collapsed after a day of yard work in May of 1914. Two days later, he was dead; his death certificate listed the cause as "gastric ulcer."

Unlike other residents of the Archer Home, Andrews had family members with whom he exchanged correspondence, and he had often written them letters about his life at the home, noting the "frequency of deaths" there. Andrews' sister Nellie Pierce came to clean out her brother's belongings and found within them a letter from Amy Archer-Gilligan "pressing Andrews for money." Pierce took this and the letters describing the frequent deaths to the Connecticut state attorney as well as the local newspaper, the Hartford Courant.

A local newspaper investigated Amy Archer-Gilligan

Per the Hartford Courant, Nellie Pierce asked Amy Archer-Gilligan about the note in which Archer-Gilligan asked Franklin Andrews for a loan "as near $1,000 as possible." Archer-Gilligan denied the request at first, but then later claimed she had received a gift from Andrews for $1,000. Pierce hired a lawyer, who demanded Archer-Gilligan pay back the money. She did so, saying it was "not because she could not keep it but because she did not feel it worth quarreling over," as reported by the Courant in a cover story published on May 9, 1916.

Clifton L. Sherman, managing editor of the Courant, was fascinated by Pierce's story as well as rumors he'd heard about what was happening at the Archer Home. He assigned assistant city editor Aubrey Maddock to write the story. Maddock looked at local death certificates and discovered that 60 people had died at Archer House since 1907 and "Forty-eight of them, a number declared to be far in excess of the normal death rate at an institution of this kind, have been reported since January 1, 1911." Reporters also investigated Archer-Gilligan's shopping habits and found she "had purchased substantial quantities of arsenic at pharmacies in Windsor and Hartford, which she said was to deal with a rat problem. The Windsor pharmacy was also selling Archer-Gilligan morphine, which she consumed with regularity."

The police got involved as more evidence came in

Faced with this evidence, the Connecticut state police began an investigation. According to the Windsor Historical Society, authorities exhumed the bodies of several former residents of the Archer Home, including that of Franklin Andrews. During an autopsy, they discovered enough arsenic in Andrews' stomach "to kill half a dozen strong men." Per the Hartford Courant, Amy Archer-Gilligan was arrested on May 8, 1916. She reacted calmly to her arrest, stating, "I will prove my innocence, if it takes my last mill. I am not guilty and I will hang before they prove it." When asked about the suspicious number of deaths in her home, she explained, "Well, we didn't ask them to come here but we do the best we can for them. They are old people, and some live for a long time while others die after being here a short time."

A former tenant, Loren B. Gowdy, testified at the trial that he and his wife Alice had inquired about moving into the Archer Home in May of 1914. They were specifically interested in the room then occupied by Franklin Andrews and a roommate. Archer-Gilligan told them she would arrange for them to take the room on June 1, 1914. Andrews died on May 30, and the Gowdy's received a telegram on May 31 letting them know the room was ready. They moved in a few days later and paid Archer-Gilligan a fee of $1,000. Alice Gowdy suddenly died on December 4, 1916. Her body, once exhumed, was found to contain arsenic.

Not the typical serial killer

Amy Archer-Gilligan was only tried for the murder of Franklin Andrews, but she was indicted for poisoning and killing four other people: Alice Gowdy; her husband, Michael Gilligan; and two other Archer Home residents, Charles A. Smith and Maud Howard Lynch. All but Lynch were found to have died from arsenic poisoning; Lynch died from strychnine poisoning, as reported by the Hartford Courant. Authorities suspected that she killed at least 20 people who had lived in the Archer Home, if not many more.

Archer-Gilligan's trial began on June 21, 1917 and was a media circus. She was found guilty on July 13 and sentenced to death by hanging. Her lawyers appealed and she was granted a reprieve. Eventually, a new trial was ordered and began on June 12, 1919. Lawyers mounted an insanity plea as the defense, but Archer-Gilligan ended up admitting to second-degree murder on July 1, 1919. She was sentenced to life in prison and began her sentence at Wethersfield State Prison before being moved to the Connecticut Valley Hospital, then referred to as a "state hospital for the insane." She died there on April 23, 1962 at the age of 94, described thus by the Hartfort Courant: "Mostly she sat in a chair, dressed in a black dress trimmed with lace, a Bible on her lap, and prayed." It's not hard to imagine how she inspired the characters of Abby and Martha Brewster, shown above as played by Jean Adair and Josephine Hull in the movie adaptation of Arsenic and Old Lace.