How The Golden State Killer Was Finally Caught

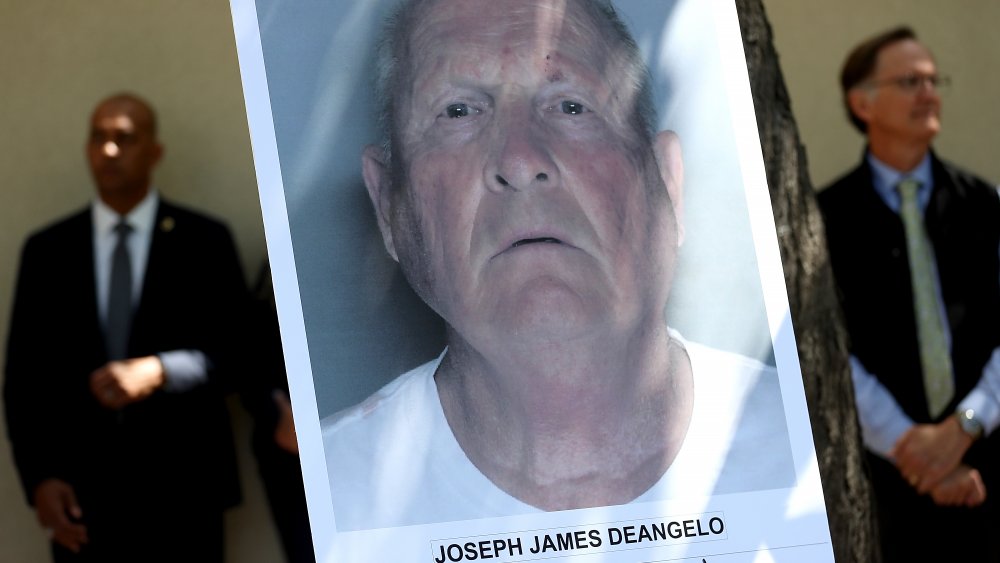

In early 2020, an old case came to a close and it gave a lot of people a lot of hope — hope that no matter how long it's been since a crime has been committed, there's still a chance for justice. When Joseph DeAngelo was finally arrested, it meant the end to decades of terror. Let's put it this way: according to the BBC, his hearing was held in the ballroom of a university, in order to accommodate the number of victims and victims' families who wanted to attend.

During the 1970s and 80s, California residents were terrified: they were in the hunting ground of a serial killer. Strangely, it wasn't an odd thing. The BBC says that the era was known as the "golden age of the serial killer," and there were a lot of them stalking the US at the time.

This one, though, was particularly terrible. He didn't just kill, he raped, robbed, terrorized, and stalked his victims. He got away with it for a long, long time, and he may have slipped into infamous anonymity if not for the determined, dogged work of one crime writer. Let's talk about how the Golden State Killer was finally identified and captured.

The Golden State Killer's range of crimes are shocking

According to Vulture, the criminal who would become known as the Golden State Killer was linked to around 60 victims from across the state of California, and ultimately connected to brutal crimes across seven different counties. He was hunting between 1976 and 1986... at least. And he was terrifyingly organized: between June of 1976 and July of 1979, for example, one of his favorite targets was the middle-class homes of Sacramento County. He'd target a home, then sneak into the always single-story house before the attack, learning the layout, disabling porch lights, finding any guns they might have and removing the bullets, and even stashing ropes around the house to use later. The attacks continued before and after the physical violence, too: he would often call victims to taunt them.

He blinded women with flashlights and threatened to kill them if they'd resist. He would tie up parents or husbands, balance plates on them, and tell them that if the plates fell, he'd start cutting off fingers. He targeted everyone, from teenage girls and minors to couples. Early on, he would leave his victims alive. Then, in 1978, he shot and killed Katie and Brian Maggiore as they walked their dog, and later killed a surgeon named Robert Offerman and his girlfriend, Debra Alexandria Manning. After that, the BBC says that he made sure to kill those he targeted. The numbers got higher and higher, and still, he stayed in the shadows.

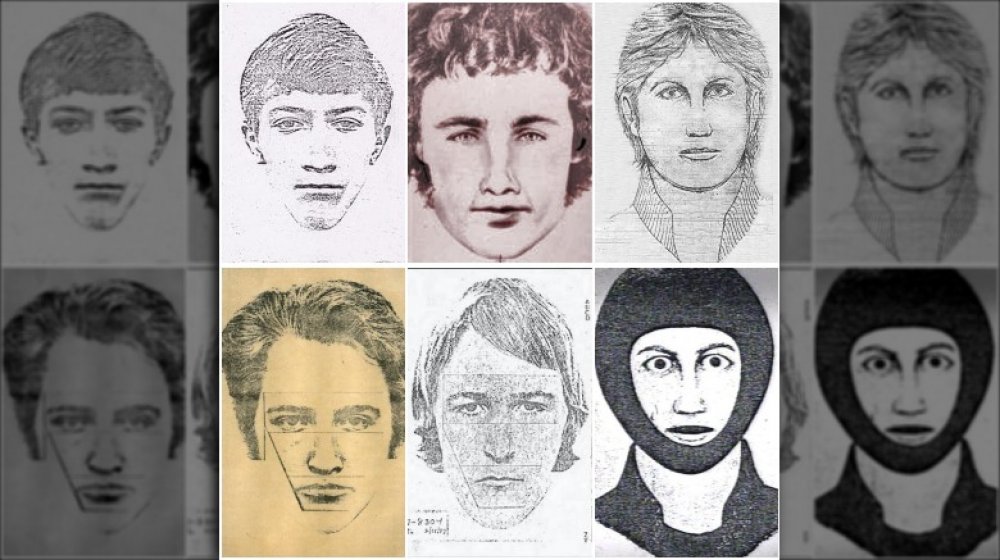

The Golden State Killer was thought to be a bunch of different criminals

So, how on earth did he stay on the loose? There were a few things at work here, says the BBC. For starters, the attacks occurred hundreds of miles apart, leading investigators to go down the usual route of questioning family members or spurned lovers, assuming they weren't connected.

Once it was determined that some of these crimes were happening in groupings, it was first believed to be the work of a handful of different serial killers/serial rapists. They were even given different nicknames: the East Area Rapist, the Visalia Ransacker, the Original Night Stalker. Lieutenant Paul Belli, who has worked the case since 2008, put it this way: "We had excellent investigators back in those days who worked really hard on the case. Nobody could have predicted that the southern California cases were our guy."

Also? This was the 1970s, and DNA technology was nowhere near what it is today. When Janelle Cruz was murdered in 1986, her killer's DNA was recovered from the scene. But it was more than 10 years before that DNA was matched to DNA recovered from other crime scenes, like the murders of newlyweds Keith and Patti Harrington. Then, it matched DNA from two late-1970s rape cases in Contra Costa County. And it snowballed from there, as a new task force was assembled to share information across the different jurisdictions.

The Golden State Killer's last known victim

According to The Washington Post, the pattern was the same for a while. Every few weeks — for years — the unknown assailant would break into a home, raping and (in later attacks) killing his victims. But in 1981, it sort of stopped.

After a five-year hiatus, though, there was one more killing. The Cruz family lived in Irvine, California, and in May of 1986 most of the family was on vacation. But 18-year-old Janelle Cruz had just gotten a new job at a local pizza place, and stayed home to work. She had a friend over one evening, and he would later say that they'd heard strange noises outside before he left. They'd written it off as a cat.

The next day, the real estate agent who was showing the house found Cruz's body. She had been raped and bludgeoned to death, likely with a pipe wrench that was missing from the home. Although it was years before she was officially linked to the dozens of other crimes committed across California, her mother and her sister, Michelle Cruz White, were among the first officially contacted when an arrest had been made (via BBC).

Who was the Golden State Killer, and why did he stop?

The killer, says The Washington Post, was Joseph James DeAngelo Jr. The news broke in 2018, and that brought up the question: who was this person? DeAngelo, they say, was likely helped in his bid to avoid detection by his police training. The Vietnam Navy veteran joined the Exeter police force in 1973, when an article in the local paper boasted, "James DeAngelo believes that without law and order there can be no government and without a democratic government there can be no freedom."

He joined the police in May, married in November, and even as he investigated crimes in Exeter, a rash of burglaries happened in the nearby town of Visalia — around 85 of them. He transferred to another department outside of Sacramento in 1976, and that's when a serial rapist started stalking the Sacramento suburbs. He continued to patrol alongside cops looking for him, and in 1979, theft charges brought an end to his police career. That's also when he started killing.

Why did he stop? According to ABC News, DeAngelo said he'd killed on the order of an inner voice named Jerry, and when Jerry disappeared in 1986, he stopped. He stayed in the area, taking a job in a Save Mart warehouse, raised his kids, and terrified neighbors with his temper. He had a daughter and granddaughter living with him when he was arrested at his meticulously-kept home. Neighbors and coworkers — some who had known him for decades — knew he was strange, but never suspected he was a killer.

A woman named Bonnie

According to the Los Angeles Times, there's an eerie puzzle piece that fell into place with DeAngelo's unmasking. He'd met Bonnie Colwell when she was 18 and he was 23. She was the beautiful young college girl, he was the worldly Vietnam vet: he took her scuba diving and shooting, he taught her how to ride a motorcycle, and it wasn't long before they were engaged. But things got stranger and stranger — he was hunting out of season, flaunting the law, and reveled in carving up illegally shot deer — and finally, she hit her breaking point. They were students in the same Abnormal Psychology class at Cal State Sacramento when he asked her to cheat for him, and she not only refused, she broke off the relationship she'd had a bad feeling about for a long time.

After a failed attempt at forcing her to go to Reno for a marriage at gunpoint, DeAngelo faded into the background. He bought a house a few miles from Colwell and her new husband and by this time, he was already sneaking into homes, stealing trinkets, and peeking through windows while wearing no pants.

It was only after his arrest Cowell learned that in 1978, a woman he had raped described the emotional breakdown of her attacker, who had started to cry into her pillow and say, "I hate you, Bonnie. I hate you, I hate you, I hate you."

The crime writer that kept the case alive

For years, the case of California's serial rapist and killer went cold. According to Biography, it was the journalist Michelle McNamara who made sure no one forgot. McNamara's interest in true crime came because of a horrible event: Vulture says she was only 14-years-old when a young woman she knew from church was murdered. Her killer was never found — and it was a disturbing fact of life she discovered she couldn't stand for.

It was her husband — comedian and actor Patton Oswalt — who ultimately encouraged her to start a true crime blog, which opened the door for her career as a crime writer, and led her to the long unsolved California case. And she did some ground-breaking work: in addition to putting together pieces that had long been ignored and pulling on all kinds of strings people in more official positions couldn't, she uncovered a treasure trove of files that hadn't been looked at in years. It was 2016, and she was convinced that somewhere within the 40 boxes of files and evidence was the name of the killer.

Unfortunately, McNamara would not live to see the arrest of the man she had nicknamed the Golden State Killer. Laboring under the pressure of solving the case and writing a book about it, she worked to exhaustion, then accidentally took a combination of medications — including Xanax — that ended up being deadly. She died on April 21, 2016.

Here's how the DNA turned into a smoking gun

Investigators, says The Washington Post, had the killer's DNA. But that DNA didn't match anyone in the FBI's national database, and without a way of narrowing down who it belonged to, it didn't do them much good. It was, they said, just "a big flashing question mark."

Until 2018. That's when law enforcement looked somewhere new: GEDmatch, a service that collects voluntarily given samples of DNA. It's like Ancestry, or 23andMe. People submit their DNA in hopes of finding relatives or more information about where their ancestors came from, and in this case? They found a DNA sample that was a partial match to the Golden State Killer.

That person wasn't the killer, of course, but it gave them a place to start. Detectives then went back through the family, and one named popped: DeAngelo, the former officer who had lived in the area of the attacks as they were happening.

The actual evidence is still sealed

On June 29, 2020, a crowd would gather at the ballroom of a Sacramento university — the same one DeAngelo graduated from in 1972 — to hear his confession and his plea. The hearing would do a few things: one, it would override the need for a lengthy criminal case, but it would also mean that the evidence investigators had gathered against him would remain sealed — including exactly how they'd traced his DNA through an unspecified family connection. They had also agreed that the death penalty was off the table.

According to the Los Angeles Times, most of that family was staying pretty quiet — save a few, including DeAngelo's brother-in-law, Jim Huddle. DeAngelo married Huddle's sister, Sharon, in 1973 — while he was working in Exeter as a police officer. And he believed he could answer a few unanswered questions, like what happened to all the jewelry that disappeared from victims' homes but was never recovered. Huddle says he believed those stolen treasures were all melted down and formed into something else, like the gold bar DeAngelo had once shown him, claiming it was South African coins.

Huddle has also spoken about how, after DeAngelo was fired from the police department, he had threatened to kill his former chief. Huddle had tried to talk him out of it, at the same time the attacks in the East Area stopped, and ones in southern California began. Huddle says of his brother-in-law: "He was never a real heartwarming person."

A confession... but it's not closure for many

DeAngelo, says ABC News, was arrested in 2018 and on June 29, 2020, he plead guilty to 13 counts of first-degree murder. That absolutely doesn't sound like much, compared to the list of crimes associated with the Golden State Killer, and it's not. Part of the plea deal involved his admission of guilt in dozens of other cases... that he wasn't charged for. As prosecutors read the list, he repeated a version of what he'd said in an interview in 2018: "I did all those things. I destroyed all those lives." In front of victims and family members, he repeated, "I admit," after every count.

According to The Guardian, the confession came after three days where the victims who had survived him — and the family members of those who didn't — spoke. And it was a little bittersweet. Yes, families have gotten closure: as Ken Smith, brother of murder victim Katie Maggiore said: "After your sentence, you will be a nobody. You are not worth any more of my family's time. You can't hurt anybody again."

But here's the thing: the dozens of rapes committed between 1976 and 1979? He'll never be formally charged for them, even though he's admitted to them. The statute of limitations is up. He was still sentenced to life without parole.

Michelle McNamara was unofficially given a lot of the credit

When news broke that the Golden State Killer had been arrested, those who had read Michelle McNamara's work and followed her in her quest to ID the man behind the name were quick to praise her — and there's a few coincidences that are worth mentioning. According to CNN, DeAngelo's arrest came just four days after the second anniversary of her untimely death. And the date? It was DNA Day, a "holiday" that celebrates the advances science has made in DNA research. McNamara, they say, firmly believed that in the end, it would be DNA that would find the killer — and it was.

Marie Claire took a look at just how much impact McNamara's research — front and center in the HBO docuseries I'll Be Gone in the Dark — had. They said that while her profile was incredibly accurate, police were hesitant in giving official credit. According to Sacramento County Sheriff Scott Jones, "It kept interest and tips coming in but other than that there was no information extracted from that book that directly led to the apprehension."

But according to The Guardian, the victims said differently. Many credited McNamara — and her posthumously published book of the same name as the HBO series — at DeAngelo's confessional hearing. And Vulture says that Paul Holes from the Contra Costa Sheriff's Office gave her a ton of credit, too, calling her research "a gold mine."

DNA has been instrumental in solving other cases recently, too

Finding a killer via the DNA of a family member is a fairly new thing, but when it was used in the Golden State Killer case, that wasn't a first. According to the BBC, the first time a murderer was captured thanks to family DNA was to solve the 2002 rape and murder of an elderly widow named Gladys Godfrey.

The 87-year-old Godfrey was attacked in her Nottinghamshire home, and the extent of her injuries was so severe that law enforcement didn't allow her niece to identify her body. They called it "one of, if not the most horrendous case, that we have ever investigated."

The killer remained unidentified and at large for a year, even though they had samples of his DNA from the scene. There was no match in any national database, and here's where the Forensic Intelligence Bureau comes in. They started looking for close DNA matches instead of exact, and the results were a fairly long list of names... but a list, nonetheless. After factoring in geographical information, they homed in on 21-year-old Jason Ward. The DNA matched, Ward was arrested, entered a guilty plea, and was handed a life sentence. In the UK alone, familial DNA techniques have been used in 212 criminal cases between 2009 and 2018.

It's opened an ethical can of worms

Surely, any tools that allow serial offenders to be brought to justice and put behind bars for a long, long time is a good thing... right? It turns out that it's not so clear-cut, and the use of familial DNA in criminal cases has kicked up a massive ethical debate. According to Drexel University professor of law Robert Field, one of the biggest problems is that while some DNA testing firms don't allow their DNA to be accessed by police, some do... and the distinction isn't always clear to anyone who's submitting a DNA sample.

There's another problem: most of these companies aren't updating their own policies and procedures fast enough to keep up with advances in DNA technology, and that can leave them — and their customers — open to loopholes.

PSMag says there's questions about what other doors this will open. If police have access to everyone's DNA, who else will? Will employers or insurance companies be able to use it to discriminate against applicants? Will medical facilities soon be able to access DNA samples for research? Are you cool with that?

The debate might not be entirely new — Mercury News says that California's attempts to create a DNA database in the 1990s were met with a "buzz-saw of opposition" — but with continued advances in the science, there's many that say future-proofed laws designed to protect people's privacy needs to be put in place sooner than later.