The Super Bowl: 25 Facts About The NFL's Big Game

It's the most anticipated sporting event of the year, one that consistently draws even non-sports fan to watch, even if it's just for the commercials. The Super Bowl is such an event, movements are afoot to make the following Monday a national holiday (via The Wall Street Journal). Held every year, pitting the AFC and NFC champions against each other, it's the game of all games to end the NFL season.

So, how did we get here? What happened along the way? Take a gander at all the hidden details involving the last NFL game of the year.

How did we get to a Super Bowl?

There would be no Super Bowl if the NFL hadn't rebuffed a Texas oilman. Lamar Hunt wanted to bring an NFL team to Texas, but the National Football League politely declined, reports The New York Times. Hunt responded by doing what any respectable high falutin' Texan would — he formed his own league.

Hunt convinced seven others to go along with his plan to compete with the NFL, launching the American Football League in 1960. It mostly featured college stars (with the AFL often outbidding NFL teams for their services) and castoffs from the NFL. In short, the AFL was as second-class citizen as it could get. The media mocked them, the NFL ridiculed them, and even CBS — which carried NFL games — refused to report AFL scores.

But that plucky little league wouldn't go away, and they did provide some flashy football. The games were more "modern," with more passing, more flamboyance from the players, and just more fun. The NFL feared a bidding war for players, so they proposed a compromise: merge the two leagues (via History). In June of 1966, they did just that — the AFL and NFL would continue their regular league play, but the winner of each league would then meet at a neutral site facility to determine the world champion. They even came up with a catchy name for that game, one that would live forever: The AFL-NFL World Championship Game.

Wait, what?

The first AFL-NFL World Champions

By now, the Super Bowl has been one of the most watched sporting events in the world for a long time, but it had to start at some point, and at that time it was known by another name, the AFL-NFL World Championship Game. In 1966, the NFL and the American Football League combined to create one major football organization throughout the U.S., and the top teams from this new league faced off the following year for the first time.

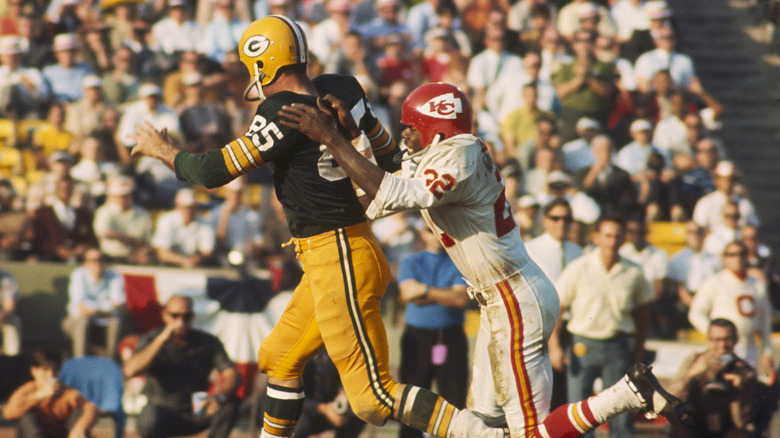

The historic match began the tradition of taking place on neutral ground with the Memorial Coliseum in Los Angeles as the venue. In their entertaining showdown, the Green Bay Packers managed to crush the opposition, the Kansas City Chiefs, with some impressive plays, like the one-handed catch of wide receiver Max McGee that led to a touchdown (via NFL.com). The rather one-sided victory ended in final score of 35-10, but it would take at least a couple years before the Packers would be considered Super Bowl champions since that title for the game did not yet exist. Then in 1969, the championship match received the official name and Roman numerals, and it has stuck ever since.

The real story of how it got called the Super Bowl

Obviously, calling it the AFL-NFL World Championship game wasn't going to fly — AFL-NFLWC is about as awkward as it comes, initially speaking. But the folks running this got big brains, so they quickly came up with a better name: The World Championship Game. No really, officially that was the name of what we know as Super Bowl II and III. It was only via the quick wit of Lamar Hunt, who noticed his children play with a Super Ball toy, that we got the name "Super Bowl" in time for the fourth game. We know that's true because the venerable old Gray Lady herself, The New York Times, reported it as fact in 1983.

But that's what people like to call "fake news" nowadays. In truth, Hunt put out his first mention of "Super Bowl" in 1966 after meeting with broadcast networks to discuss coverage (via The Atlantic). The game wasn't even set in stone until December 1, 1966 — it was scheduled only 45 days later. But the game was already unofficially the "Super Bowl" by then — as early as September 1966, the Los Angeles Times called the upcoming event the Super Bowl. The Washington Post did the same about a week later. Logically, this makes sense, as the game was clearly "super" — the New York Times even called it a "superduper" game in June 1966, months before the season even started.

Plus, calling an end-of-season game a "bowl" wasn't groundbreaking — colleges had been playing bowls for 50 years at that point. A bunch of headline writers, independent of each other, probably just put the two words together and created a legend. In short, Hunt's Super Ball story, while cute, is about as real as the Browns' chances of winning a Super Bowl.

Roman numerals were adopted very early on

Like the title, Super Bowl, the Roman numerals used to differentiate each historic match from the other is now such a traditional aspect that it would be easy to believe the ancient symbols were always used. But it was only after the first two competitions, in 1969, when the old name, the AFL-NFL World Championship Game, was replaced with the old school numerals.

The reason for adopting Roman numerals for the Super Bowl was both quite simple and logical. Since the year of the competition is never the same as the year the season starts, using the unique symbols was an easy way to help prevent any confusion. Furthermore, it would not be surprising if the rationale also included that it looks cool and adds a level of prestige to the event.

The hungover hero

Your grandfather's NFL isn't your NFL. Today, rules are in place to assure safety, and athletes are serious about their diets and careful to keep in tip-top shape. Meanwhile, players in the "back in my day" era would smoke cigarettes, as SB Nation shows, at halftime as casually as today's athletes chug Gatorade.

But Green Bay Packers wide receiver Max McGee had all the smokers beat. His Packers appeared in the first World Championship Game, and he was a backup, not supposed to play at all. So, as the famous story goes, McGee stayed out with two stewardesses (as they were called back then) until 6:30 a.m. the day of the game. And they weren't playing parcheesi.

Before the game, McGee ominously warned starting wide receiver Boyd Dowler not to get hurt, saying (via Sports Illustrated), "I was out all night and I had a few more drinks than I should have." Unfortunately, Dowler went and did just that, reinjuring his shoulder. A hungover McGee went in and, somehow, shined, with seven receptions for 138 yards and 2 touchdowns. McGee, the happy-go-lucky partyboy, was able to pull it together when his team needed him and contributed to a rare, alcohol-fueled Super Bowl victory.

The rise and fall of an unknown Super Bowl star

Often in sports, the phrase "came out of nowhere" is thrown around to describe a virtually unknown player who excels in a big spot. Should that ever need a photo to accompany it, they should use Timmy Smith. When the team now known as the Washington Commanders used a fifth-round pick on him in the 1987 draft, there weren't a lot of people who had even heard of him. He suffered injuries his Junior and Senior years of college at Texas Tech, and barely played. Even in the regular season, Smith only mustered 29 carries over the half of the 14-game schedule he actually played.

Starting running back George Rogers struggled in the playoffs, so Smith got his opportunity and performed well, but nothing was expected from him in the Super Bowl. Head coach Joe Gibbs surprised Smith the morning of the game, by informing him he was getting his first start of his career, and on the biggest stage of them all, as per the New York Daily News. He responded with a Super Bowl record 204 rushing yards and two touchdowns, as the Redskins won 42-10.

Unfortunately, this was not the start of a great career. Smith faded quickly after his unbelievable performance in the Super Bowl. He was out of football by 1990, and quickly started running with the wrong crowd. In 2005 he was arrested for cocaine trafficking and served 18 months in prison.

The most unlikely Grammy nomination ever

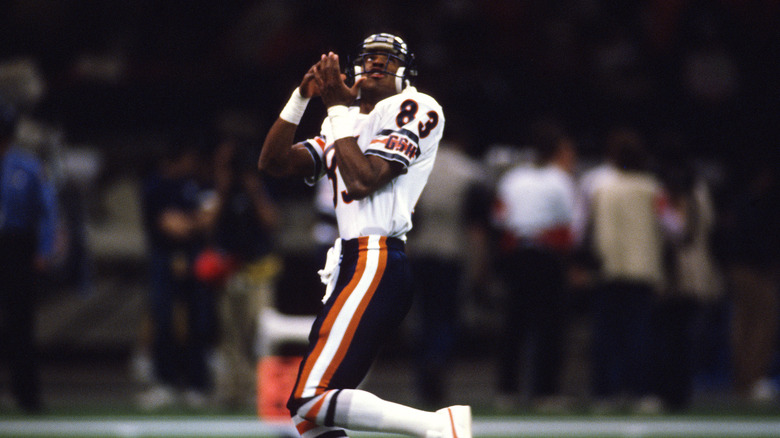

The Super Bowl XX champion Chicago Bears were something unseen at that time — a flashy team that could back up the talk. The '85 Bears finished the regular season 15-1, crushed the New England Patriots in the Bowl 46-10, and are recalled as one of the greatest teams ever. When you're that good, you need the quintessential 1980s vehicle to show off: a song and an MTV video.

Wide receiver Willie Gault already had ties to the record industry when executives approached him about doing a song about his Bears. A song called "Kingfish Shuffle," a parody of "Amos and Andy," received new player-specific lyrics and became the "Super Bowl Shuffle" (via Grantland). The music video was so '80s it might as well have been neon. The Bears didn't really take it too seriously — it was boastful and certainly fit their image, but it was more of a parody than anything. A parody of a parody basically. Mockception.

But the public, Bears fans or not, loved it. It hit No. 41 on the Billboard charts, and the bulk of the money went to Chicago charities. Plus, amazingly enough, the song was nominated for a Grammy. They could've won "Best R&B Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal," but Prince took it home.

Oh, and the Patriots countered with their own song and MTV video, "New England, The Patriots, and We." It ... didn't sniff a Grammy, and basically went over about as well as their performance on the Super Bowl field.

The crazy prop bet that started them all

You already know the Super Bowl is a heavily gambled event. Besides the traditional bets, there's a host of other crazy prop bets one could take. There's "will the coin flip heads or tails," "which team will get the ball first," "how many times will a player dab" and the immortal "will Peyton Manning cry" from Super Bowl 50 (via USA Today).

If you love betting on these dumb lies, you can owe it all to a Refrigerator. William Perry was a rookie defensive linemen for the '85 Bears. To get a little more blocking help on short yardage plays, Chicago inserted the massive lineman — nicknamed "The Refrigerator" due to his size — to plow the way for running back Walter Payton. And then, on a lark, Perry got to carry the ball — lo and behold, he waddled into the end zone and scored a touchdown!

"Fat man in the end zone" caught the imagination of fans, and he became an overnight sensation. When the Bears reached Super Bowl XX, Las Vegas saw an opportunity to take a few suckers' cash. Bookmaker Jimmy Vaccaro installed a pretty ridiculous wager: will Refrigerator score a touchdown? He put it at 40-1 (a $10 bet will win you $400), and odds rose to 75-1, until the national media caught wind of it and people flocked to Vegas to get a piece of the Fridge.

Logically Payton, one of the greatest running backs in NFL history, would be given the opportunity to score if the Bears got close, but gamblers kept wagering on Perry to the point where the odds dropped to only 5-1. And yes — in the 3rd quarter of a 37-3 blowout, with the Bears sitting on the one-yard line, Refrigerator entered the game and scored him a touchdown. Vegas got smeared on the wager, but in the long run, they came out way on top, because if not for that 1986 prop bet, very likely none of the other crazy wagers would exist.

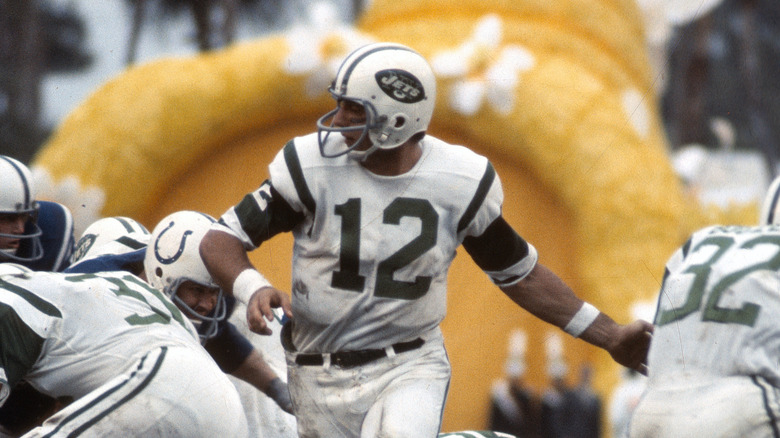

The whole truth behind Joe Namath's guarantee

Popular myth persists that the New York Jets, as 18 point underdogs, had no chance against the Baltimore Colts, in Super Bowl III. As such, the Jet's flashiest player, Joe Namath, responding to a Colts fan's hecking with, "We're going to win the game, I guarantee you," as per The New York Times, and then delivering, was basically the work of a hard-partying soothsayer.

But what the mythmakers (and betting line makers) didn't realize was that the Jets were very well matched for the Colts from the start. The New York players knew Baltimore couldn't beat them (via Newsday) — Namath simply said the same thing they all said privately. The 18-point thing was more "oh, those crazy AFL clowns" than anything else.

The real crazy thing about "the guarantee" is that Namath's comments didn't trend on Twitter or make ESPN's bottom line as BREAKING NEWS (mostly because it was 1969). He said it late Thursday night, and they appeared in a Miami Herald article the next day, per The Washington Post — the guarantee never got much more attention until the day of the SB, when broadcaster Curt Gowdy mentioned it briefly. Even that didn't cement the legend, as reports right after the game didn't mention Namath's guarantee. That was up to Father Time, and the mythmakers blessed with the powers of hindsight.

The story behind the biggest ball-drop in SB history

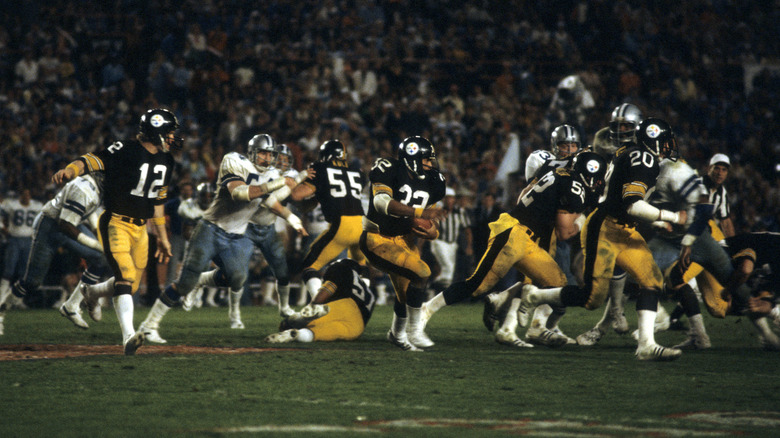

Modern football has finally learned how to use the tight end properly. Prior to 1980, however, most were lumbering giants known more for blocking than hands and skill. Jackie Smith was an outlier — when he retired, no tight end caught more passes nor had more yards than the future Hall of Famer. But all anyone remembers is that time he cost the Dallas Cowboys a Super Bowl.

But see, Smith really didn't cost Dallas a win, but he did drop a wide-open touchdown reception in the third quarter of Super Bowl XIII. Smith, in his last season in the NFL, attempted to catch a pass near the goal line. Unfortunately, the throw was low, and Smith slipped on the turf, failing to catch the ball. Now, there was still 17 minutes in the game, and Dallas truly lost by settling for a late field goal instead of the touchdown needed to stay alive. But none of that matters to the memories of fans, who see "drop" and go "THAT."

Dallas radio play-by-play man Verne Lundquist said it best after the drop: Smith must be "the sickest man in America" (via Sports Illustrated). He most likely was. Smith was called a scapegoat. Fans ridiculed him, even in front of his children. They even ridiculed his children, taunting them in their sporting lives. The drop follows him and rarely is his Hall of Fame career the thing that jumps to mind when you hear "Jackie Smith." We'd be sick too.

You know what never gets mentioned? Jackie Smith got the Cowboys to the Super Bowl that year by ... scoring a touchdown! His touchdown catch tied the Atlanta Falcons en route to a 27-20 comeback win, but that's not juicy enough for angry soundbites.

I'm going to Disney World!

The famous phrase started by accident. Michael Eisner and his wife dined with Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager, a duo who just became the first to fly non-stop around the world. Asked what they planned next, Rutan deadpanned, "I'm going to Disneyland" (via Sports Illustrated). After a good chuckle, Eisner's wife Jane said, "You know, that's a good slogan."

With Super Bowl XXI rapidly approaching, Disney acted quickly. They looked at both teams and tried to determine MVP candidates, eventually zoning in on the two starting quarterbacks: the Giants' Phil Simms and the Broncos' John Elway. Since it was the first time The Mouse had to front some guaranteed cash, Simms got $75,000 win or lose (if he said it or not), while Elway was offered less (at least $15,000, though possibly almost $50,000). Simms' Giants demolished the Broncos — as he jogged off the field in victory, a tap came on his shoulder. "Disney!", the voice shouted. He almost forgot about it, because after 60 minutes of football and visions of championship glory dancing in your heads, a random ad spot is furthest from your mind. But he said the line, and created a tradition.

The famous slogan (and payday) bled into other sports and cultural events. Disney, who's as much about marketing as it is about magic, quickly got wise, and had every player (even the scrubs) sign a contract to say the line — this way, they could assure they'd get what they needed, no matter who won. It also helped them not use the Ravens' Ray Lewis — he was the MVP of Super Bowl XXXV, helping his team cruise to a 34-7 win over the Giants, but due to his alleged involvement in a double murder the year prior, Disney had no interest in him. Quarterback Trent Dilfer got pegged to say the line instead, because the only murder he had anything to do with, was that of the Giants' hopes and dreams.

Everything you know about Apple's 1984 ad is a lie

It's the greatest Super Bowl commercial ever — just ask every listicle ever. Apple procured Ridley Scott to direct their Super Bowl XVIII commercial to usher in a new era and play off the Orwellian notion of totalitarianism. The ad was an immediate hit. And we mean like right after the commercial aired, game announcers Pat Summerall and John Madden commented, as per The National Museum of American History, "Wow. What was that?"

Apple gets a lot of play off the story that it only aired once, but here's the thing: it aired more than once. Apple may have only paid for one airing, but TV news replayed the commercial numerous times because of the buzz it created, as software engineer Andy Hertzfeld recalled. And besides that, it aired once before the Super Bowl, at 1 a.m. on December 15, 1983, after the sign-off signal for local Twin Falls, Idaho, station KMVT. Why? It was an old industry trick to become eligible for awards.

There was also a 30-second version that aired weeks before the Super Bowl, one that ran in major markets, plus the much-more-minor West Palm Beach, Florida market. Why West Palm? IBM's computer base was in that market, that's why. Like you didn't know Steve Jobs was that petty.

Halftime performers have to be content with exposure

A somewhat upsetting aspect of careers that most creative professionals have to deal with is doing work not in exchange for money, but rather publicity. While certainly helpful, most would probably prefer a decent paycheck, and the hope is that once one has reached a certain level of success, cash becomes the norm. Yet, the Super Bowl halftime show is a major example of how that is not always the case.

The NFL does at least make sure to provide for the extravagant production costs to put on the spectacular performances, which is definitely important to note. On the other hand, any musician who agrees to do the event will not get a single cent of that budget, no matter how famous or accomplished they are. Instead of a monetary incentive, artists get the opportunity to perform in front of a worldwide audience that in recent years can reach as many as 100 million people. Without a doubt, that kind of exposure and publicity is extremely valuable on its own.

The NFL prefers to keep the cold out of the competition

In 2018, football fans in the Midwest were pleased to attend Super Bowl LII relatively nearby while the rest of the spectators had to make the rare trip to the far northern city of Minneapolis. While the game was certainly not the only time the NFL selected a cold climate locale to host their biggest event, as SB Nation highlights the others — but to say that group is small would be an understatement

Before both dome stadiums and retractable roofs became a more common feature, the vast majority of Super Bowl showdowns have occurred in southern states simply for the better weather. In fact, the NFL preferred warm, sunny venues to such an extent that before 2010, 33 out of 44 of the matches took place in Florida, California, or Louisiana.

Since then, the organization has made a solid effort to include the northern masses more often, with Indianapolis chosen in 2012 and New Jersey two years later.

Limited edition coins are now used for the toss

Over the several decades of the competition's existence, the Super Bowl has become so important to diehard football fans that much of the memorabilia associated with the matches has become incredibly valuable. These days, that is such the norm that it can be easy to forget that simple objects did not always carry the same significance, like the coin used for the toss to kick off the game. When talking with Florida Today, Vince Bohbot, executive vice president for the Highland Mint, revealed that in the early days, "Nobody knew what they used for the flip coin, they used quarters or whoever had whatever in their pockets."

Then in 1994, the situation changed dramatically when the Highland Mint in Melbourne, Florida, began crafting specialized coins used exclusively for the NFL's top showdown. To the joy of both fans and collectors alike, the historic decision suddenly created a new limited type of merchandise deeply engrained within the pregame ceremony of the game. And a lot of people can join in on the fun because out of the 10,000 coins minted, only 100 are given to the league, while the rest are available for anyone to purchase for the fairly affordable price of $99.99 each. Understandably, the exact coin used for the toss always has much more value, however, as some can get up to over $10,000 in auctions.

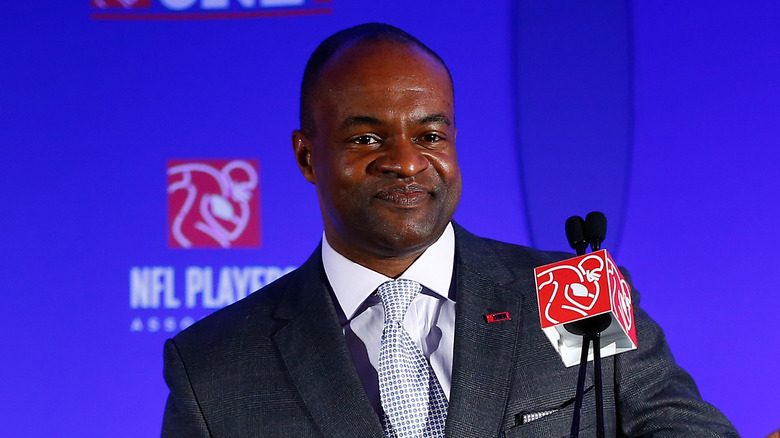

The Players Association guarantees everyone gets paid

Making it to the Super Bowl is a massive accomplishment for the teams involved, but it is also devastating for the players who do not leave the event with a win. Thankfully, though, the athletes have the powerful Players Association to back them up and make sure that no one goes home empty handed. Even the losers are from the second-best team in the league, which is certainly worthy of praise as well.

So, in the agreement hashed out between the NFL and the Players Association, the victors are provided with an extra $157,000 on top of their salaries, while the losers are still awarded with $82,000 each, reports The Hill. Those figures also seem to increase every year, which means that in less than a year, Super Bowl victors may earn as much as $228,000. Seeing as how the players are the most vital part of the competition, that makes sense for such an incredibly profitable performance.

The most dominant teams in the Super Bowl

Of the many teams within the NFL, there are a few that stand out as exceptional given the number of times they have won the most prestigious competition of the sport. Yahoo compiled the top 15 franchises that have dominated the league with their Super Bowl victories, and tied for first place are the New England Patriots and the Pittsburgh Steelers with six championships for each. Also, close at their heels are the San Francisco 49ers and the Dallas Cowboys, who only need one more win on the grand stage to equal their rivals.

Unsurprisingly, many of these teams are the same ones that have made the most appearances in the epic face off as well, with the Patriots featuring in 11 of the matches, along with the Steelers, Cowboys, and Denver Broncos all tied for eight, based off the stats provided by Sports Illustrated.

The huge cost of Super Bowl tickets

It may be surprising to hear, but not too long ago it was possible to purchase tickets to the NFL's premiere event for less than a grand. In fact, access to the original championship match cost an incredibly low amount to today's standards at only $12 a ticket, as per USA Today. However, that all changed in 2009 when fans had to spend at least $1,000 to see the Pittsburgh Steelers play against the Arizona Cardinals at Super Bowl XLIII.

Since then, the situation has only gotten considerably worse. For Super Bowl LVII in 2023, the average ticket price was an enormous $9,915. This in itself was a massive increase from the $8,900 cost just one year prior. Such a level of inflation is quite outrageous, but then again, more than enough fans are willing to pay it, and that probably will not change if the price rises even higher next time around.

Super Bowl teams get as many as 150 rings

Super Bowl rings may be some of the most iconic symbols of the historic matches, but many may not realize just how many are crafted for each competition. Not only are teams given 150 pieces of the stylish jewelry, but even the losing teams are honored with conference championship rings to acknowledge how far they made it in the season even if they did not ultimately win, according to NBC Miami.

While the NFL will provide some funds up to $7,000 per ring, the rest is up to the franchise on how extravagant they want to make them from there. The Los Angeles Rams is one of the most elaborate examples, for their rings included a miniscule replica of their home field, SoFi Stadium. With such additions, it is no surprise that some individual rings could be valued at more than $100,000 when put up for auction.

Many advertisers do not want to pay to say Super Bowl

In the decades following the adoption of the name Super Bowl for their elite competition, the NFL has fiercely protected the trademark. So much so that the organization is willing to take anyone to court who has the audacity to use the title in promotions without asking for permission first. What is even more intense is that the league has done the same with the phrase Super Sunday as well. For those who are willing to get permission and cough up the cash, the price is extreme, with Budweiser paying $1.2 billion for the privilege, says the St. Louis Business Journal.

The strict rule applies to pretty much any business, no matter how small, so all sorts of alternatives have been used over the years to get around it. Many will simply allude to the "Big Game" of the weekend, or something along those lines, while others have gotten far more creative. One of the most hilarious examples was when Stephen Colbert referred to the "Superb Owl," but even then, his bosses over at Viacom were frightened of facing the NFL's wrath and made the comedian stop, notes SB Nation.

The losers' merchandise is given away for free

With the exorbitant amount of merchandise produced to promote every single Super Bowl event year after year, it is nice to know that the NFL makes a concerted effort to make sure a lot of the goods do not simply go to waste after the event. Of primary importance is finding a home for half of the clothing and accessories that awkwardly display the logo of the losing team. To do so, the league has partnered with the nonprofit organization, Good360, whose representative, Shari Rudolph, stressed to The Hill, "We also take pains to avoid sending the apparel to a location where a flood of donated clothing could disrupt the local economy."

The NFL clearly has no desire to humiliate any team that made it to the huge match but were not able to pull off the victory, for Rudolph added, "But you definitely won't see it on anyone in America. The NFL has strict controls to ensure that the general public will never see it." Therefore, all of the merchandise is shipped overseas far out of sight of the average American to Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East.

The real cost of the priceless Lombardi Trophy

Arguably, the only item that represents a Super Bowl victory more than the iconic rings is the famous Lombardi Trophy. The impressive award is constructed entirely out of sterling silver by the renowned craftsmen at Tiffany & Co, but even so, the work of art remains extremely lightweight at only seven pounds, says NBC Philadelphia.

While the precious metal of the Lombardi Trophy gives it a worth of at least $10,000, it does cost a good amount more to make at $50,000. On the other hand, the cultural significance of the award would likely add considerably more value to it. Unfortunately, the large size and high value of the award makes it impossible to distribute multiple copies to the winning team, but the NFL has found a way around that by at least producing souvenir-style versions that are much smaller and still valuable at $1,500 each.

Tom Brady has won the MVP award the most

Football is certainly a team sport, but even so, there are always stand out players whose exceptional contributions are acknowledged with the prestigious MVP award. NBC Los Angeles compiled all of these top athletes over the years, and no player is anywhere close to beating Tom Brady's impressive collection of five MVPs. The talented quarterback first received the reward all the way back in 2001 and again almost 20 years later,

So far, the only athlete that is anywhere near Brady's record is Joe Montana with three of the awards. But since the legendary quarterback earned his last one back in the 1980s, Brady has nothing to worry about from Montana. Much more recently though, Patrick Mahomes has picked up two of the awards in the last few years, so if a current player was to threaten overcoming Brady, it would likely be the Kansas City Chiefs star.

The high cost of Super Bowl ads

For an event that attracts as many as 100 million viewers, advertisers are unsurprisingly desperate to get a piece of the action and have their product featured during the historic event, even if briefly. The station that plays the game is fully aware of this and takes advantage as much as possible, charging enormous rates for screen time or promotions associated with the event.

Even in the early days, Super Bowl ads cost a decent amount at around $37,500 in the 1960s, according to Parade. In the decades that followed, the price has increased considerably to reach as much as $7 million in 2023. But marketing departments are happy to shell out that kind of cash for the exposure that a 30-second commercial entails and have been doing so for quite some time. In 1995, the price went above $1 million.

Brothers have competed against each other twice

Sometimes football can be a family affair. Over the years, there have been a number of teams that have pitted brother against brother — and in some cases brothers as teammates. NFL.com gives a rundown of several siblings, with some quite the dynasty like the Mannings. In 2023, all eyes were on the Kelce brothers, when their epic face off during Super Bowl LVII saw Travis Kelce of the Kansas City Chiefs play against his brother Jason of the Philadelphia Eagles — the first time the game has hosted to brothers on opposing teams. In the end, the Chiefs won, and the two embraced in the aftermath, but not without Jason stating in jest, "F*** you, congratulations" (via Twitter).

That wasn't the first Super Bowl showdown between two brothers — although it did not exactly happen on the field per say, but rather on the sidelines as coaches Jim and John Harbaugh led their teams against each other for Super Bowl XLVII in 2013, according to Today. John was able to walk away with the bragging rights as his Baltimore Ravens barely beat the San Francisco 49ers 34-31.