What It Was Really Like To Perform With Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show

By 1872, William Frederick Cody had done an awful lot in his 26 years. Biography states he had prospected in the Pikes Peak Gold Rush of 1858 and was a Pony Express rider by age 14, fought in the Civil War, and killed some 4,280 buffalo during the 1860's. Center of the West says the self-enamored frontiersman had been producing his own plays about the West for some time when he happened to meet Edward Judson. Under his nom de plume, Ned Buntline, Judson wrote exciting dime novels about the Wild West that included stories of the legendary "Buffalo Bill" Cody. Shortly after seeing someone portray his character on a New York stage, Cody decided to exploit his own adventures. "I'm not an actor—I'm a star," he declared.

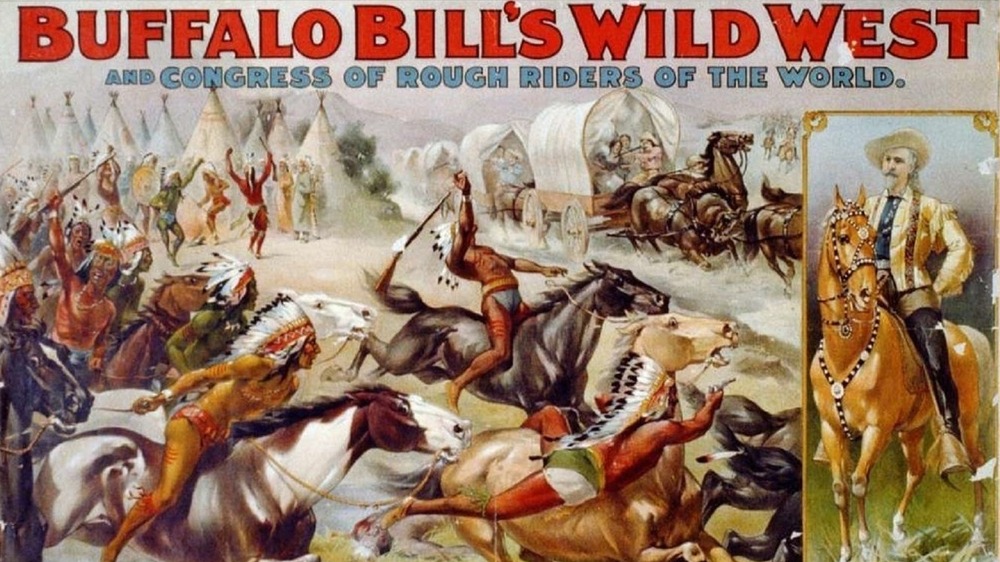

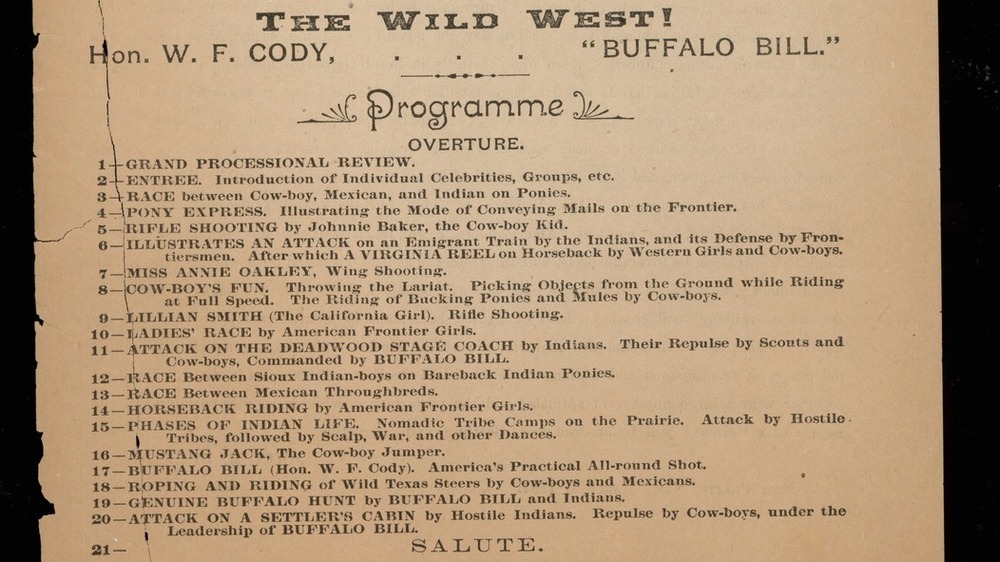

By 1883, inspired by other Wild West shows performing in America, Cody had founded his own grand production, "Buffalo Bill's Wild West." The show was more elaborate and colorful than any before it, featuring live exhibitions of battle scenes with Natives, equestrian feats, rope tricks, sharp shooting, and other exciting performances. The show remained wildly popular for 30 years, with upwards of 1,200 performers making appearances over time. Some of them, such as Annie Oakley, Sitting Bull, and even Cody himself gave audiences a taste of the "real" West. So what was it like to work for this enigmatic and charming man? Read on for the intimate details of Buffalo Bill and his Wild West performers.

The beginnings of Buffalo Bill's Wild West show

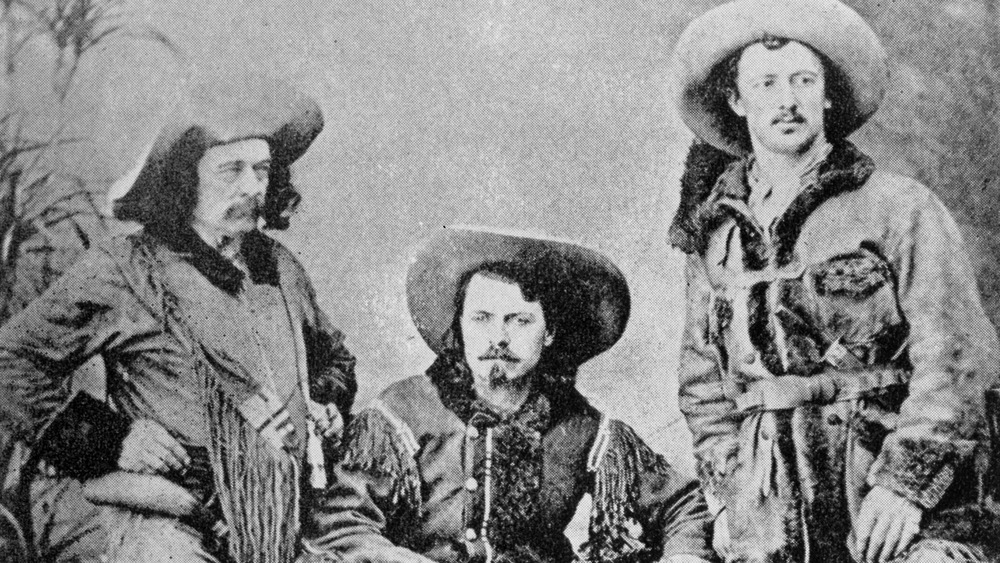

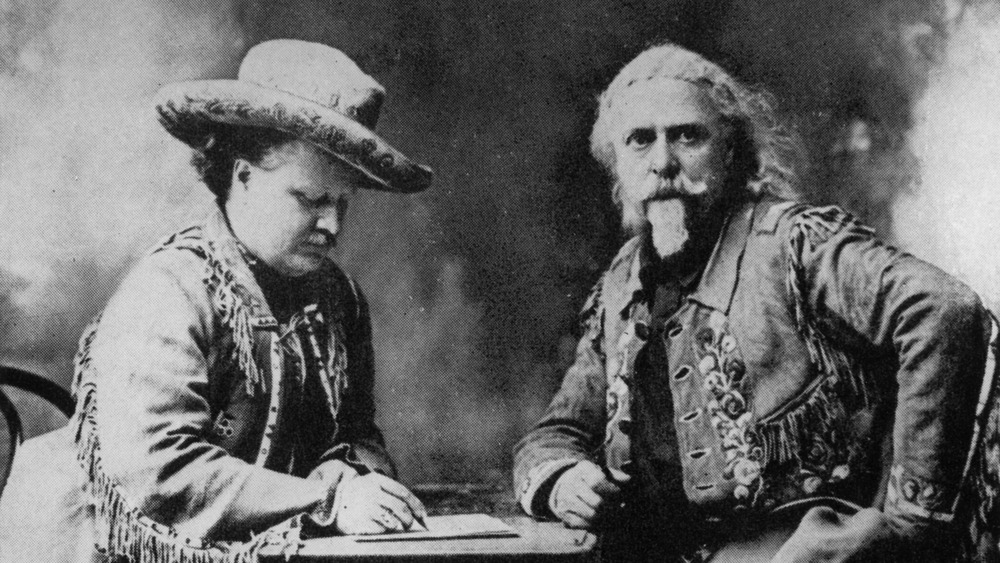

What does it take to create a jaw-dropping live performance show? Even for the experienced showman William Cody, it took more than the "flamboyant theatrical clothes" he actually wore on the battlefield back when he scalped Cheyenne warrior Yellow Hair during General Custer's campaign against the Natives in 1876. It also took more than the inspiration provided by Ned Buntline (pictured, left, with Cody and Texas Jack). Cody also needed a partner, and initially found one with a dentist-turned-exhibition shooter named Dr. W.F. Carver. One of the earliest ads for the show appeared in the Rock Island Argus in Illinois, billed as "Buffalo Bill's and Dr. Carver's Wild West" featuring "100 actual performers." These included Carver, "champion shot of the world."

HistoryNet relates that even with Carver aboard, the first season of the show was "lackluster" at best. What Cody needed was true "star power," which he found by hiring two well-known characters in 1885: Sitting Bull, who was largely responsible for the defeat of Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn, and expert markswoman Annie Oakley, whom Cody met while she and her husband, Frank Butler, were performing at a circus in New Orleans. Sitting Bull nicknamed the petite Oakley "Little Sure Shot." Over time Cody would hire other well-known celebrities of the day to make his show the biggest and best it could be.

How authentic was Buffalo Bill's Wild West show?

William Cody did more than incorporate famous figures into his show. The performances included numerous reenactments, from buffalo hunts, Natives attacking wagon trains, Pony Express rides, and stagecoach robberies, to train robberies and the "Grand Finale," initially known as "The Attack on the Burning Cabin." Cody eventually also took on another partner, a wealthy Irishman named Evelyn Booth who "provided much financial support" to the show in 1886 and recorded his adventures with Cody in his personal journal. In spite of the show's popularity, however, HistoryNet points out that famous battle scenes like the one at Little Bighorn left out the fact that Native women and children were killed in the skirmish.

So how authentic was the show, really? PBS submits that although notable people like General William Tecumseh Sherman, Mark Twain, and Elizabeth Custer felt the performances were historically accurate, that wasn't always the case due to creative license. Audiences cared little for hard-to-swallow facts, Cody reasoned, choosing instead to capitalize on entertainment value instead. Thus some performers, including May Lillie, Annie Oakley, and Lillian Ward, weren't even natives of the Wild West, whose history was more romanticized than real. But audiences loved the show. According to Legends of America, by 1900 Cody "was probably the most famous American in the world."

A cast of hundreds

Cowboys. Indians. Women. Men. Children. Staff workers. Real horses and live buffalos. These were the members of Buffalo Bill's Wild West, which Center of the West says numbered around 500 by the late 1890's. Granted, it took a lot of performers to put on the show; one image circa 1887 aptly illustrated the numerous cast members involved. In addition to performers, X Roads says the show also required enough "stagehands and laborers" to pack, load, and unload "massive sets" which were put up before each show and taken down for transport afterwards. Over time, these workers would come and go.

One of the reasons it is hard to put a finger on exactly how many people were in William Cody's employ is because the number varied from year to year. In 1887, for example, HistoryNet says the entourage included "100 whites, 97 Indians," and over 200 horses and other stock when the show went to England (pictured). That was roughly half of the staff Cody commandeered in America when his show was unceremoniously left out of Chicago's Columbian Exposition in 1893 for being "too vulgar." The determined showman simply set up across the street from the expo instead; a map of the area shows Buffalo Bill's Wild West occupying 14 acres that included a campground for 200 cowboys of mixed heritage, troops from "five great armies of the world," and 450 horses.

Native Americans in Buffalo Bill's Wild West show

Some of the most exciting aspects of Buffalo Bill's Wild West were the battle scenes carried out by real Native Americans. Some of them, says PBS, had actually been at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876—which William Cody emulated along with other scenes of the Natives attacking Anglo settlers. Being cast as the bad guys unfortunately enhanced the belief that the Natives were wrong to defend their land at Little Bighorn even though it had been given to them by the American government, and that they were the ones who introduced the scalping of their enemies (which in truth is attributed to Spanish explorers). How could Cody exploit his Native performers like that?

Legends of America confirms that it was often Cody himself who fought and conquered the Natives during his show. Notably however, the showman "genuinely believed" that he was doing the right thing by employing Natives, thereby removing them from the reservations where the Bureau of Indian Affairs considered many of them to be "dangerous." Traveling with the show allowed these people to retain their language and customs, and receive money they never would have had otherwise. Cody also promoted the Natives as "The Former Foe—Present Friend, the American," thereby emphasizing that the reenactments were scenes of the past, not of the present, and also that the show's "warriors" were now deservedly on equal ground with other nationalities.

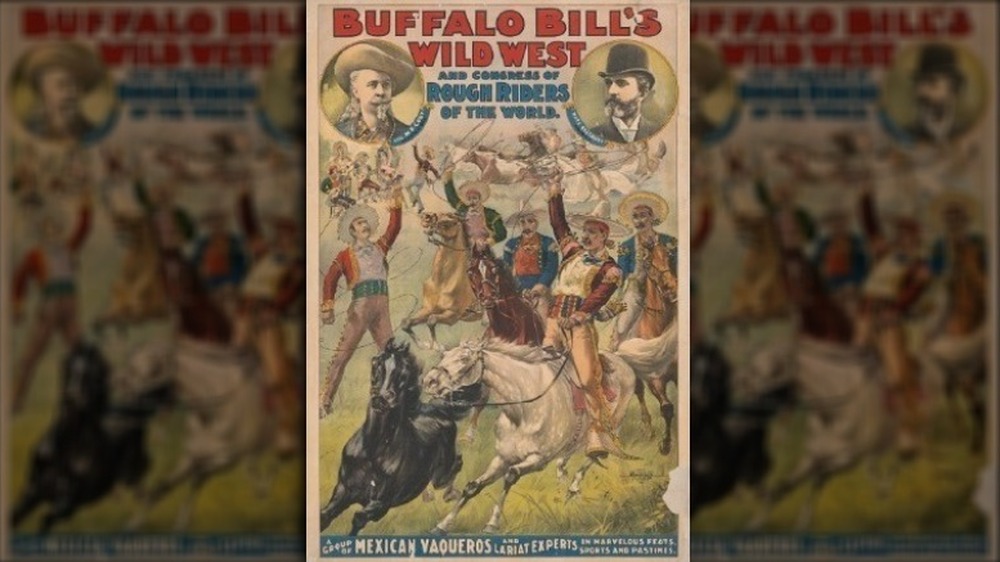

Ethnic diversity made up much of the cast

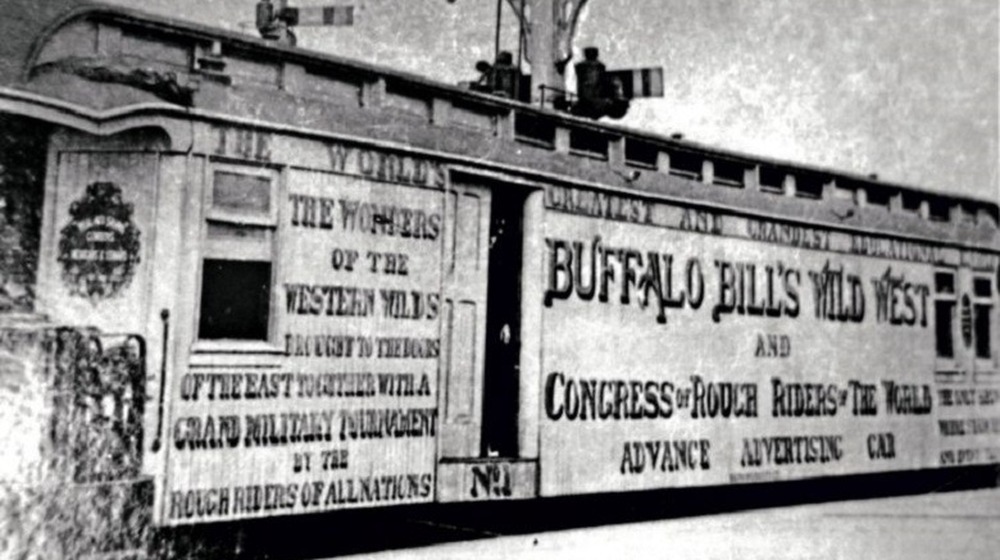

Buffalo Bill's Wild West was not just made up of Anglos and Natives, but also several performers from other ethnic backgrounds. Center of the West says that "persons of color" were initially a mainstay of the show, although their roles as cowboys were later phased out in favor of other ethnicities. One of them, Voter Hall, was advertised as "a Feejee Indian from Africa" in 1885. By 1892, William Cody had a new partner, Nate Salsbury, whom writer Brendan Murphy identified as heading "a popular black faced minstrel troupe" called Salsbury's Troubadours. It was Salsbury's idea to create a performance, the "Congress of Rough Riders of the World," which incorporated military troops and professional horsemen from all over the world. These included cowboys from Cuba, Hawaii, Japan, and the Philippines. Writer Kathryn White called the decision "a drawing table for American identity."

As Cody realized how important Mexican vaqueros were to the West's development, says writer Pablo A. Rangel, he began including them in the Congress of Rough Riders performance along with other nationalities. By 1894, the show also featured "Cossacks, gauchos, Arabs," soldiers from Europe and Russia, Cuirassiers from Germany, and men from the Pacific Islands, all of whom promised to "uniquely and fascinatingly complete the ethnological scope" of the world, according to the show's program. Together, these performers made a complete, if "romanticized" representation of the cowboys and soldiers who roamed the West.

Famous cast members were a big draw

In his book, Celebrity Sells, author Hamish Pringle surmises that celebrities "have always captured the imagination of the public." The practice of hiring famous people to influence one's brand goes back a long way, including the days of Buffalo Bill's Wild West. Even before the show was formed, it is notable that back in the 1870's William Cody performed with his friend, James Butler "Wild Bill" Hickok, who originally served as Cody's mentor. By the time Cody formed his Wild West show, he knew that he needed big names for a big draw to his performances.

Celebrities of the era who performed with Buffalo Bill over the years included not just Annie Oakley and Sitting Bull, but others as well. Iron Tale, an Oglala Lakota, later served as a model for the "Indian head nickel." There also was fellow showman Gordon William "Pawnee Bill" Lillie (pictured, who later formed his own Wild West show), famed bulldogger Bill Pickett of the 101 Ranch, and a lanky Texas cowboy, William Levi "Buck" Taylor, whom Arizona historian Marshall Trimble calls "the Original King of the Cowboys." Another important member of the show was another Oglala Lakota, Red Cloud, who had appealed to the plight of his people in Washington, D.C. and whom Indian Country Today says was in Buffalo Bill's show during 1897.

Was Calamity Jane a cast member of Buffalo Bill's Wild West show?

Buffalo Girls, the highly entertaining mini-series of 1995, has done much to propel the story that wild woman Calamity Jane (shown here drinking with her buddy, Teddy Blue Abbott) once performed in Buffalo Bill's Wild West. Biography says Jane joined the show in 1895, while The Shooter's Log claims she was fired for drinking, among other things. But although Georgia's Morning News of 1895 is one of several newspapers to confirm Jane really did know William Cody, there is no evidence she was ever in his show.

Calamity Jane biographer James McLaird submits the Calamity Jane/Wild Bill story was drummed up by Jean McCormick, who claimed to be Jane's daughter in the 1940's. McCormick was later disproved, but it is a fact that both Jane and Red Cloud did join Colonel Fred Cummins' Pan-American Exposition in 1901 according to the Center for the West. When Jane left the show and drank away her money in New York, she met up with Cody and asked for some assistance in getting back to the Black Hills, says writer Amy Reece. Cody gave her some cash for the trip, but she was broke again by the time she reached Chicago. Jane did eventually make it back to her beloved West, dying in 1903.

A performance for Queen Victoria

In 1886, according to Buffalo Bill in Bologna: The Americanization of the World, 1869-1922, William Cody received the opportunity of a lifetime. Nate Salsbury had negotiated for an official invitation from the London American Exhibition for Buffalo Bill's Wild West to perform in 1887. Cody accepted and prepared to set sail in March aboard the State of Nebraska along with over 130 crew members and nearly 220 livestock. Two months later, the show premiered to rave reviews. HistoryNet quotes the Illustrated London News as proclaiming, "It is new, it is brilliant, it will 'go'!"

Among those attending that first show was the Prince of Wales—the son of Queen Victoria. Her Majesty soon sent a message to Cody, requesting a private performance at Windsor Palace. Britannica says the show coincided with the Queen's Golden Jubilee, and Cody was happy to comply. The day was indeed grand, and the Prince of Wales even rode in a stagecoach with Cody as he fought off "marauding Indians from the driver's seat." One of the performers, Black Elk, would remember the performance for "Grandmother England," and that the Queen talked to and shook hands with several cast members afterwards, including himself. She was so kind that Black Elk later lamented that "maybe if she had been our Grandmother, it would have been better for our people." Center of the West says the show returned to Europe three more times.

Buffalo Bill's Wild West show on film

Buffalo Bill on the Silver Screen: The Films of William F. Cody confirms that inventor Thomas Edison, who had developed his kinetoscope studio in New Jersey, extended an invitation to William Cody to bring a few of his performers east to be caught on film for the very first time. The end results were "Bucking Bronco," with cowboy Lee Martin (pictured), "Sioux Ghost Dance" featuring Native American performers, and Annie Oakley shooting at various targets. These early scenes made Buffalo Bill even more of a star in his own right.

More films would follow: Blackhawk Films would later produce more footage of the show that was captured in 1898, 1902, and 1910. Notably, the latter year was shot after Pawnee Bill purchased James Bailey's interest in Buffalo Bill's Wild West. Cody found film quite useful as it enabled him to promote his shows, show his respect for the Natives, and capture such epic moments as a meeting with Prince Albert of Monaco. Even after his show ended in 1913, says University of Oklahoma Press, Cody "fully embraced the film business," hoping to record the American west's history as he knew it.

On the road with Buffalo Bill's Wild West show

How does one lug around hundreds of performers, animals, sets, and other necessities for a traveling show? It wasn't easy as the entourage stayed on the move; not until 1895 did James Bailey of the Barnum & Bailey Circus partner with Cody to use two official trains to get around, says the Journal Star. Each train consisted of some 50 cars, including large stoves from which to feed the employees who napped in sleeping cars on the train and lived in tents at the shows. Center of the West notes that in 1908 there were a total of 780 mouths to feed, with food purchased in whichever towns the show was performing.

During 1899 alone, Buffalo Bill's Wild West performed 341 shows in 132 cities, traveling a total of 11,000 miles. Performers were rarely given a chance to settle in for the next show upon arrival. WXPR says that in 1900, the trains no sooner pulled into Rhinelander, Wisconsin than performers disembarked behind William Cody, who led a parade around the downtown area on his horse. Following each performance, the "mess wagon" would move on to the next town as the show props were disassembled and loaded for transport.

The tragedies of show business

Early on, Buffalo Bill's Wild West nearly went broke with the collision of two ships on the Mississippi River in 1883—one of which was transporting William Cody's troupe. Denver Library explains that the entire troupe was on the steamship W.P. Thompson when it collided with "another vessel" and promptly sank. Nobody died, but the accident cost Cody some $20,000. Next, terrible weather hampered three months' worth of shows, putting Cody in the hole for another $60,000. By 1888, the show was back on its feet when Antonio Esquivel, a Mexican cowboy with the show, was accidentally shot in the face, says the Cody Archive. Esquivel lost sight in one eye as doctors worked to save the other eye. He was, thankfully, able to stay with the show.

Next, says HistoryNet, officials became concerned about Sitting Bull (pictured here with Cody), who had left the show and whose increasing "ghost dances" were said to protect Natives and even protect them from bullets. Although Cody allegedly tried to quell the fuss, Indian agent James McLaughlin tracked down Sitting Bull in 1890 and killed him. Eleven years later, the show was traveling from North Carolina when one of its trains collided with another train. Our State reports "hundreds of show horses and exotic animals" died in the crash and several performers were hurt including Annie Oakley, who was so severely injured that she eventually left the show.

Buffalo Bill goes belly up

The 1901 train crash of Buffalo Bill's Wild West was the beginning of its end. Although the show was filmed several times between 1902 and as late as 1910, shooting events lost their popularity in favor of baseball and football, says Center of the West. The allure of professional rodeos was another factor as the excitement of the "Old West" faded. Also, there were now dozens of other Wild West shows, including that of Pawnee Bill, with whom William Cody partnered in 1908, according to Legends of America. By 1913, however, a show in North Carolina had "many empty seats, probably because of a conflict with commencement exercises in the local schools and colleges."

Buffalo Bill's Wild West was officially bankrupt by July 1913. Cody turned to making films, but Our Press says his first endeavor, The Indian Wars, "was not a financial success." Today, only a few minutes of footage from the movie survive. Four years later, says the Library of Congress, Cody died in Denver. He was 70-years-old. Today, visitors can see his grave (pictured) in nearby Golden. Elsewhere, two museums, Buffalo Bill's Boyhood Home in Wyoming (which was moved from its original location in Iowa) and the Buffalo Bill Cody Homestead in Scott County, Iowa, are reminiscent of Cody's childhood. And in Nebraska, Buffalo Bill State Historical Park preserves Cody's 1886 mansion.