The Assassination Of Julius Caesar Explained

Over 2,000 years ago, in the Roman Republic, 44 BC, a murderous deed was undertaken that would come to reverberate through the centuries as one of the most shocking and ill-conceived in Western history, an incident that remains highly divisive in how it is interpreted even today. The incident was the vicious and bloody assassination of the all-powerful consul of the Roman Republic, Gaius Julius Caesar, which occurred on March 15 — the now infamous Ides of March.

Politically-motivated killing wasn't exactly rare in Caesar's day. According to the CTC Sentinel, "in the ancient world assassination featured prominently in the rise and fall of some of the greatest empires." So why has the assassination of Julius Caesar remained infamous among all others of the same period? Here's why the circumstances around Caesar's death — and the subsequent repercussions for the Roman Republic — have remained so contentious to this day.

Julius Caesar's immense popularity

To understand the assassination of Julius Caesar we must look back to the years before 44 BC, how his rise to power had been achieved, and what exactly his position comprised at the moment of his murder.

US History notes that Caesar was a highly able and popular figure: he "was a man of many talents. Born into the patrician class, Caesar was intelligent, educated, and cultivated. An excellent speaker, he possessed a sharp sense of humor, charm, and personality. All of these traits combined helped make him a skilled politician."

But the former general was also a hero of the lower and middle classes for his military exploits. A general, as well as a politician, within the supposedly democratic Roman Republic, Caesar had covered himself in glory with a long campaign against the Gauls (pictured), Celtic people who lived in modern day France. In Ancient Rome, such campaigns led to the accrual of political power, not just in that they brought glory to Rome but also in that the spoils of such successes led to greater loyalty of a general's legions — who would, at the end of the day, back up his political power. Per the academic Robert Whiston, Caesar himself was a highly generous leader.

Julius Caesar amassed huge power

Once he was in charge, Julius Caesar "enacted several beneficial measures for Rome. He increased the size of the Senate for broader participation and opened citizenship to more foreigners," argues National Geographic. With such seemingly progressive policies, it's no wonder that Julius Caesar was popular.

But the years before Caesar's assassination were not exactly characterized by political harmony, as Caesar also worked to bulldoze his way through the check and balances that kept Rome a republic. This, perhaps, is the most important point to keep in mind: today, it is common to think of Caesar as an emperor. He wasn't. Rather, he had joined an uneasy alliance with fellow politicians Pompey the Great and Marcus Licinius Crassus, with whom he colluded to ensure domination of the Senate, promising to back each other's policies and ensure each was voted in turn to the position of consul. As the World History Encyclopedia explains, this subversive alliance — which worked to forward the allies' individual interests, rather than any collective ideal — soon fell apart. Crassus was killed in battle in 53 BC, after which Pompey and Caesar turned on each other. After political skirmishes in the Senate, Caesar took the decisive action of crossing the Rubicon river (pictured) with some 40,000 of his troops in 49 BC, plunging the Republic into what would become known as Caesar's Civil War.

Caesar emerged victorious, and in 44 BC claimed the title Dictator Perpetuo: the dictator in perpetuity of Rome.

Marcus Brutus was bred to oppose absolute power

As US History notes, the title of dictator was typically bestowed by the Senate for a fixed term of around six months, as a way of quickly giving the consul a temporary boost in executive power to solve critical problems, such as uprisings against the Republic. And Julius Caesar was keen to visibly demonstrate his new all-encompassing power. "In all processions an ivory statue of Caesar was to be carried alongside the statues of the Roman gods – and all this was done without objection from Caesar. This arrogance became increasingly more evident as time passed," states the World History Encyclopedia.

Such displays ran entirely against the ideals of the Roman Republic, and bred dangerous resentment among other prominent Romans, who grew concerned that Caesar was positioning himself to be crowned king and bury the Republic once and for all. One figure who would become central to the subsequent assassination of Caesar was Marcus Junius Brutus. Like many Romans, Brutus was descended from military stock who had defended the Roman Republic in previous generations: per Britannica, Brutus' ancestor, Lucius, was a famous rebel who had driven the Etruscan Kings from Rome centuries earlier. In this way, Brutus had it in his blood to protect the Republic from encroaching tyrants.

Brutus' friendship with Caesar made his rebellion especially shocking

In the millennia since the assassination of Julius Caesar, it is the name of Brutus (pictured) which has echoed down the years as that most associated with the murder, becoming in the process a byword for betrayal. But why?

Brutus' betrayal of Caesar stands out among all others because of the long and complex history between the two men. During Caesar's Civil War, Brutus unexpectedly sided with Caesar's enemy, Pompey the Great, per STMU History Media. Brutus was captured by Caesar's victorious forces at the Battle of Pharsalus, but according to the Roman historian Plutarch: "Caesar also was concerned for his safety, and ordered his officers not to kill Brutus in the battle, but to spare him, and take him prisoner if he gave himself up voluntarily, and if he persisted in fighting against capture, to let him alone and do him no violence; and that Caesar did this out of regard for Servilia, the mother of Brutus."

Brutus' mother Servilia was Caesar's mistress for around 20 years, and some sources — such as Thought Co, and including Plutarch – suggest that there is a "possibility" that Caesar was in fact Brutus' father, which explains Caesar's preferential treatment of his one-time enemy, and makes the latter's ultimate betrayal all the more subversive.

Caesar's opponents formed 'the Liberatores'

But Brutus was just one of many who took exception to Julius Caesar's ongoing accrual of power. "there were the usual, old enemies of Caesar – friends and supporters of Pompey who sought both high office and profit. Next, there were those who many believed were friends of Caesar, people who, while being rewarded for their loyalty, disliked many of his policies," argues the World History Encyclopedia. "And lastly, there were the idealists – those who respected the Republic and its ancient traditions. Individually, their reasons varied, but together, they believed the salvation of the Republic depended on the death of Caesar."

Brutus and other former allies of Caesar began to meet in secret, to plot the dictator's downfall. Among them was Brutus' cousin, Decimus, who, reports Historia Civilis, had been a long-time Caesar loyalist, having served under him for five years in the conquest of Gaul and fought to contain uprisings against Caesar during the civil war. Another, Gaius Cassius Longinus, had previously fought against Caesar on the side of Crassus, and, later, Pompey, but had received a full pardon from Caesar, who was keen to exploit the talented soldier's military prowess, per the same source.

Beginning with the agreement of these three men that Caesar must be killed, the conspiracy grew, with the number of would-be assassins — who adopted the name "The Liberatores," — reaching an unwieldy total of 60.

The Liberatores debated Caesar's assassination

To undertake a conspiracy of assassination involving 60 people was extremely risky. As Historia Civilis notes, such a number is "too many to keep a secret," especially in a period of political volatility and shifting loyalties; who could say that one of those involved would not expose the conspiracy for their own ends? All 60 of the Liberatores were senators, each with their own particular relationship with Julius Caesar and objections to his continued accrual of power. The recruitment of experienced senators was necessary to lend potential legitimacy to the plan, but it also meant that The Liberatores became a multi-headed hydra, a troupe of opinionated figures with conflicting ideas. As such, debate over exactly how Caesar was to be killed went on for many sessions, as all the while the conspiracy risked being exposed.

Per the same source, the Liberatores found themselves under pressure for a number of other reasons. It was agreed upon that the murder must be committed in a public place, otherwise it would run the risk of seeming self-serving and therefore illegitimate. And as the World History Encyclopedia notes: "The conspirators realized the attack had to be soon and swift as Caesar was making plans to lead his army on a three-year campaign against the Parthians, leaving on March 18." After much debate, the place and date were chosen: the Senate meeting on March 15, at the Theater of Pompey (modern ruins pictured).

A plan for a purge nearly split the assassins

Despite agreement about the need to assassinate Julius Caesar and the formation of a plan by which to execute it, critical disagreements haunted the Liberatores and threatened to form a wedge between the ringleaders of the conspiracy in the crucial days before the Ides of March.

What troubled the conspirators — rightly, as the events following the assassination of Caesar would attest — was how the political dice would fall in light of the power vacuum that would follow. As Plutarch writes, Cassius (pictured, with Brutus, in a still from a 1953 film) was especially wary of Caesar's ally Mark Antony, a loyalist — and, supposedly, a monarchist — who was serving as co-consul alongside Caesar for the year and who might potentially take up the mantle of dictator. "Cassius had been in favor of slaying Antony as well as Caesar, and of destroying Caesar's will, but Brutus had opposed him, insisting that citizens ought not to seek the blood of any but the 'tyrant' — for to call Caesar 'tyrant' placed his deed in a better light."

As Historia Civilis explains, Brutus was instrumental in ensuring that the assassination of Caesar remained a single action performed out of necessity; to kill Antony and others — Cassius also warned of leaders of Caesarian forces whom Antony may call to for support — would in effect become a revolutionary purge, and would likely see the populace turn against them.

Caesar's warnings and premonitions

With his grasp on power continuing to tighten, Julius Caesar felt increasingly secure in his position. But as the conspiracy against him rumbled secretly on, it seemed that murder was in the air; whether through insider knowledge or instinctive foresight, a number of Caesar's inner circle began to warn the dictator of the deadly threat.

The most famous of these warnings came from Spurinna, Caesar's "haruspex" — the Roman word for a soothsayer or oracle who would scry the future through the entrails of sacrificial animals, according to Getty: "Roman sources such as Suetonius, Plutarch, Cicero, and Valerius Maximus report that an Etruscan soothsayer named Spurinna warned Caesar about danger on (or leading up to and including) the Ides." The words he is said to have uttered have become immortal: "Beware the Ides of March." Though it is implied that Spurinna had supernatural insight, Historia Civilis explains the accuracy of Spurinna's warning more prosaically, by suggesting that he may have "had contacts inside the conspiracy."

The night before the Senate meeting on the Ides, Caesar was to receive yet another warning, this time from his wife, Calpurnia, who, following a nightmare, begged Caesar to remain at home. Plutarch gives two accounts of the exact nature of the dream: he says either she dreamt that Caesar was murdered, and died in her arms, or that she foresaw his death in a dream in which the Senate voted to tear a "gable ornament" down from his house.

The bloody assassination of Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar was shaken by his wife's warnings and, per Plutarch, he resolved to avoid the Senate meeting. With just days until Caesar was due to leave Rome — potentially for many years — the conspirators were forced into action. Plutarch describes how it came down to Decimus, then, to convince the dictator to attend, and how "fearing that if Caesar should elude that day, their undertaking would become known, [Decimus] ridiculed the seers and chided Caesar for laying himself open to malicious charges on the part of the senators, who would think themselves mocked." Decimus also lied to Caesar telling him that the Senate would be voting on allowing him — in certain circumstances — to use the title "king," something that Decimus knew Caesar's ego could not resist.

As a show of Republicanism, Caesar had just days previously allowed his bodyguards to step down, according to The Collector. As such, when the unguarded Caesar arrived at the meeting, and, in his arrogance, failed to rise for the Senate, the attack began. Among the 200 gathered Senators, the 60 conspirators withdrew from their togas short knives, and, surrounding the dictator, stabbed him a reported 23 times, per National Geographic.

According to the World History Encyclopedia, at the sight of Brutus, Caesar called out: "You, too, my child!"

The immediate aftermath of the murder of Julius Caesar

The assassination of Julius Caesar — whose bloodied body now lay prostrate at the feet of the statue of his old enemy, Pompey — caused a wave of horror among the scores of Senators who were innocent of the conspiracy. Brutus reportedly attempted an explanation, but, per Plutarch, the Senators "burst out of doors [of the theater] and fled, thus filling the people with confusion and helpless fear."

The conspirators, unprepared for the reaction, attempted to explain themselves to the people of Rome. They "made their way to Capitoline Hill and the Temple of Jupiter. Brutus spoke from a platform at the foot of the hill, trying in vain to calm the crowd. Meanwhile, slaves carried Caesar's body through the streets to his home; people wept as it passed," per the World History Encyclopedia.

At Caesar's lavish funeral on March 20, the tide turned against the conspirators, when the loyal Caesarean Mark Antony — who, like many other prominent Romans, was well-versed in oratory — addressed the multitude who had come to mourn the murdered dictator. His speech, which was recorded by the historian Appian of Alexandria, according to Livius, praised the man whose reforms had so improved the conditions of Roman life, and drove the mourners into a furious frenzy. The conspirators who until this point had been given the benefit of the doubt for their actions were driven from the city, sparking a great crisis that they had not foreseen.

The assassination of Julius Caesar led to 'The Liberator's Civil War'

The Liberatores had hoped that the assassination would be surgical in its effects; that by removing the "tyrant" who had undoubtedly overstepped his bounds, the political machine of the Republic would somehow be able to continue into the future unimpeded. But, as history shows, their assumptions were dramatically and fatally wrong.

Instead of protecting the Roman Republic, the actions of the Liberatores saw Rome descend into yet another civil war, while many involved in the conspiracy were beaten to death by mobs of enraged Romans or else saw their property destroyed, according to Plutarch.

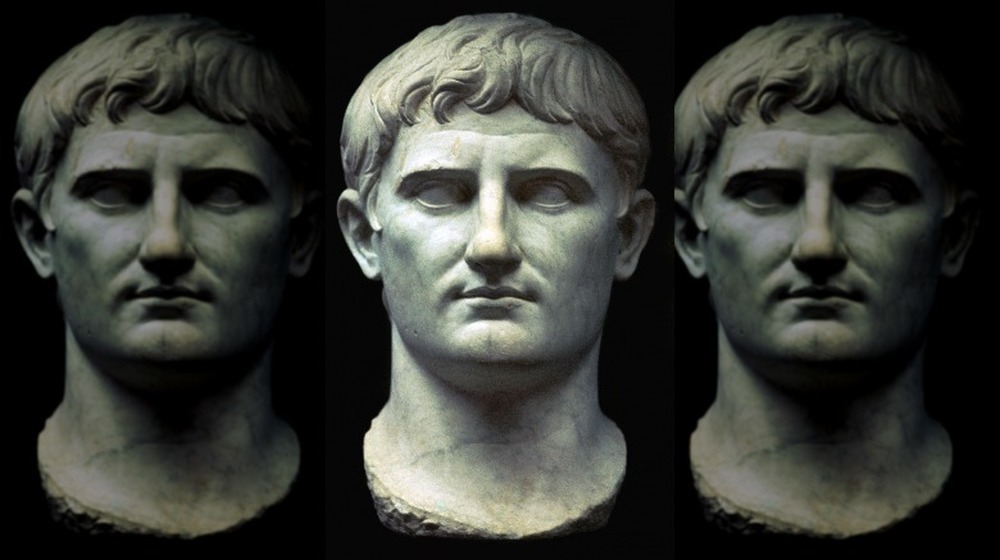

Part of the new feeling of loyalty towards the dead Caesar arose among the populace following the reading of his will, which, per the same source, dispersed a proportion of his enormous fortune among them. But Caesar's will held some other surprises too. It was believed at the time that Mark Antony, as Caesar's longtime ally and friend, stood to inherit a great deal of Caesar's wealth. However, when the will was opened, it turned out that Caesar had named his comparatively unknown great-nephew, Octavian (pictured), as his main inheritor, per UNRV. The young man had been due to accompany Caesar on his upcoming campaign; instead, he would now join forces with Mark Antony to face off against the legions controlled by the killers of Caesar for control of Rome.

Brutus and the Liberatores were defeated, heralding the end of the Republic

Britannica describes the Battle of Philippi, which occurred in October, 42 BC, as the "climactic battle in the war that followed the assassination of Julius Caesar."

Brutus found his troops in battle with the forces of Octavian, winning against Caesar's heir and capturing his camp, according to the same source. However, Cassius, battling the ferocious troops of Mark Antony in a head on assault, fared badly, and, unaware of Brutus' victory, killed himself. According to Plutarch: "after his defeat at Philippi [Cassius] slew himself with that very dagger which he had used against Caesar." Brutus decided to continue his attack, but soon found his forces scattered and running from the armies of Mark Antony after grueling close combat, according to Britannica, and Brutus' own death was imminent. "He did not fall in battle, however, but after the rout retired to a crest of ground, put his naked sword to his breast (while a certain friend, as they say, helped to drive the blow home), and so died," records Plutarch.

Like Brutus, each and every conspirator involved in the assassination of Julius Caesar met a grisly end in the years that followed, while somewhat predictably, Mark Antony and Octavian turned on each other after gaining vengeance for the dictator's death, with Octavian ultimately emerging victorious. He dismantled the Republic, and became Augustus, first emperor of the Roman Empire in 27 BC.