The Deadliest Airship Accidents In History

For as long as mankind has been looking to the sky, we've been trying to figure out how to fly. One of the first major breakthroughs came with the invention of the hot-air balloon in 1783, but there was a huge drawback: you were just sort of going wherever the wind decided to take you. Plans for a steerable version followed just the next year, but unsurprisingly, nothing ever came of it — Space says that it was so complex and difficult that 80 people were required to make the thing work.

It was back to the drawing board, and in 1852 Jules Henri Giffard set sail in his airship. That first flight covered 17 miles and he spent a lot of it turning in circles, but hey, baby steps, right? After that, dirigible technology advanced pretty quickly and it was just about 50 years later that Ferdinand Zeppelin lifted off in his five-passenger, self-named Zeppelin, and hit a height of 1,300 feet on the first flight (via ThoughtCo.) And here's the thing: That's an impressive height, but it's also a long way to fall.

Zeppelins and airships were, well, incredibly dangerous. They're essentially massive bags of floating gas that are just an ill-timed spark away from catastrophe, and many times, disaster did happen — and many, many people died.

The ill-fated polar exploration of the Italia

Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen met Umberto Nobile in 1925, but after one successful joint flight, Nobile made plans to take the newly built airship Italia on another journey — without Amundsen. He left in 1928, and the airship was almost immediately damaged while over the Alps: a sign that was ignored by everyone on board.

They did make it to the North Pole, but it wasn't long after they started heading back that the airship was pushed off course as the winds picked up. Ice started building up on the airship's skin, the engines started to fail, and the added weight meant a crash — which happened while they were still a two-hour flight from their base. The gondola was sliced off by the ice, and the balloon headed off into the sky again... along with six crewmen who were designated as "missing." Another died instantly in the impact, and nine more were stranded on the ice — most with severe injuries.

Word that the expedition was missing eventually got back to civilization, and among those who suited up to head out to search for the missing expedition was Roald Amundsen. Ultimately, the 1,500-man strong rescue operation would be somewhat successful. Eight of the original crewmen were rescued, but Norway's greatest explorer was now counted among the missing. He was never heard from again, and his remains were never recovered.

They were still over the airfield when they died

It's a little odd to think of a world where large-scale aeronautic disasters were unheard of, and according to Forgotten Airfields, the modern world discovered just how awful they could be on October 17, 1913.

That's when the German Imperial Navy airship officially known as L2 — but affectionately known by the German people as Zigarre (or Cigar) — exploded in a blaze of smoke and fire. She was over the airfield at Flugplatz Berlin-Johannisthal when RTE says the airship's balloon burst into flames, and that was followed by the inevitable explosion of the gas meant to keep the airship afloat. There were 28 people on board at the time, and those watching knew — even before they ran for the place where the passengers' cars had landed — there were no survivors.

At the time, it was the deadliest crash in the history of aviation, the ninth airship to fail spectacularly, and the incident that was also blamed for major setbacks in German aviation.

The airship that proved how deadly it could be... more than once

It's almost too crazy to believe, but in 1926, Congress approved the development of two airships that weren't just airships, they were aircraft carriers capable of hooking planes and hefting them into their cargo bays. According to Airships, the USS Akron was christened in 1931, and suffered an inaugural crash that smashed a lower fin in 1932 — a crash that would only be the first of a bunch of problems. The first deadly incident came later the same year, when on May 11, the ship unexpectedly rose. Three men of the ground crew were hauled into the air, and two were killed after falling from the ship's mooring lines.

Even as training exercises showed again and again that the Akron wasn't the scout and spy vehicle they'd hoped, she continued to tour and make publicity appearances designed to get the public on board with this whole airship idea. Then, on April 3, 1933, she headed off on a mission along the eastern seaboard. Within hours, a storm swept over her and she crashed about 20 miles off the coast of New Jersey.

Of the 76 people on board, 73 died in the cold Atlantic waters, and there's an eerie footnote here. This wasn't the first deadly airship named the Akron: according to the Library of Congress, aerial photography pioneer Melvin Vaniman died when another airship named Akron exploded in 1912, killing everyone on board.

The end of the inflatable aircraft carriers

Just a few weeks before Admiral William Moffett would die on board the USS Akron, his wife christened the Akron's sister ship, the USS Macon. According to Airships, the USS Macon started out being pretty good at what she was designed to do, and that included acting as a long-range scout.

Unfortunately, the Macon had a few modifications from the design of the Akron, and one — an upper fin that was no longer attached to the main body of the airship — would cause a fatal crash. The upper fin was first damaged by severe winds in Texas, and even though repairs were desperately needed, they didn't happen. Just a few months later, the Macon was caught in a storm over California. The damaged fin failed, leading to a series of events where helium was lost, the crew frantically scrambled to jettison weight, and the Macon crashed on the opposite coast as her sister ship had.

There were 83 people on board and only two casualties, a drastic difference from the death toll of the Akron credited to the addition of life jackets to the essential cargo. According to USNI News, though, there was another massive casualty. As a result of the Macon's catastrophic failure, the Navy decided to put an end to their plans to use airships as long-range scouting vessels attached to maritime fleets.

Today, the Macon still sits at the bottom of the Pacific.

How far the mighty have fallen

The airship known as the Roma was, indeed, mighty: She was built by the Italian government and sold to the US in 1920, and according to the New York Times, she was the largest semi-rigid airship ever built.

For all the impressive bulk of the Roma, she had some serious problems. The Virginian Pilot says that first and foremost were engine difficulties so bad that they prompted one of her regular crew, Staff Sgt. Marion J. Beall, to write to a friend, "This ship is a death trap. It's going down one of these days, and only three or four of us are coming out alive."

He was absolutely correct, and the crash happened near Norfolk, Virginia on Feb. 21, 1922. The Roma was sitting at 1,500 feet (via Flight) when she started to nose-dive, and on her way to the ground, she connected with electric lines. The resulting fire swept through the hydrogen-filled ship in a heartbeat, and killed 34 people — most of whom were identified based on their personal effects or dental records. Of the 11 who survived, most were badly injured or burned, and even as the military launched an investigation into the crash, it was pointed out just what a bad idea it was to float an entire ship on highly flammable gas.

The disaster that spelled the end of the British airship

It was a late August afternoon in 1921 when thousands of people headed out to see the test flight of the airship known simply as R38. According to the BBC, the R38 had been sold to the U.S. at the end of World War I, but on August 24 — the day of one of the last test flights in the UK before her official acceptance into the US Navy — tragedy struck.

The airship was on a test flight when fog made landing impossible, and the stress caused by a tight turn at high speed snapped the airship in half. The following explosion was so powerful that it was felt all across the city of Hull: windows shattered, people were knocked to the ground, and some were injured by flying glass and debris. Eyewitness reports (via Airships Online) described the R38 twisting in midair with the appearance of a "great wrinkle like a twisted and rolled newspaper," across the bulk.

The airship crashed into the Humber River, and in spite of rescue efforts led by the locals, 44 of the 49 people on board died in the accident. They were buried in a mass grave not far from the crash site, and the tragedy not only ended the UK's interest in using airships in their own military, but it also led to the closure of the Howden military base. Nothing remains of the airship hangars today.

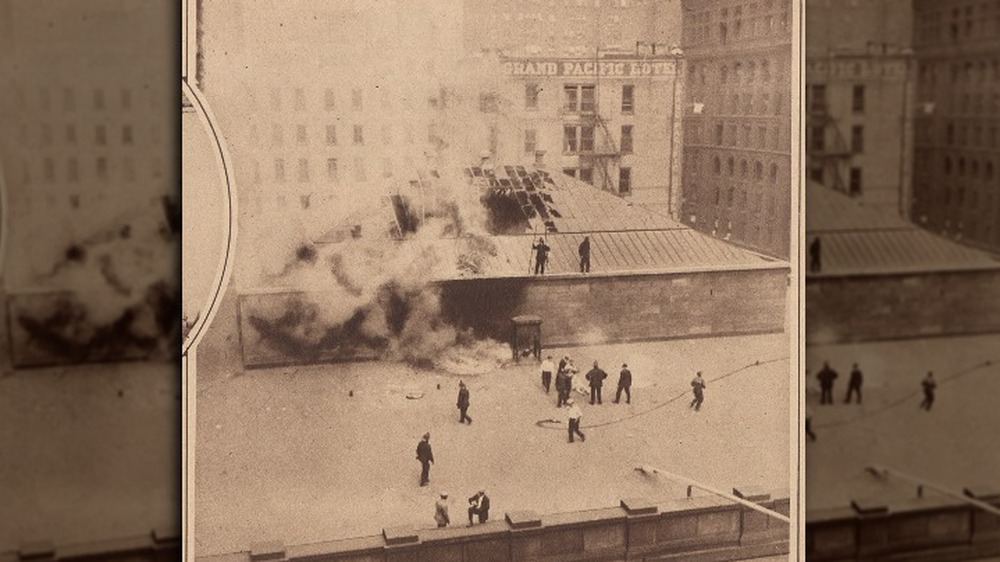

Then, there was the time an airship crashed in the middle of Chicago

The tale of the Wingfoot Air Express happened, says Slate, on July 21, 1919. The Wingfoot Air Express was a blimp owned by Goodyear, and on that fateful day Chicagology says the blimp was floating above the city as part of a test flight, and some — including the journalist George Putnam Stone — were even lucky enough to get a ride. But that luck didn't last, and at around 5 pm flames burst from the middle of the airship. It was above the Illinois Trust and Savings Bank, and plummeted straight through the bank's glass roof.

There were five people on board at the time, and although they all jumped, only two lived. The rest of the dead were bystanders, including eight regular bank employees, and two teenage messengers. Eyewitness reports are terrifying: The airship's two engines only exploded when they hit the bank floor, sending people running for the exits as their clothes burned.

Stone had been dropped off by the crew just before the airship took off on what would be its final flight, and later recounted that when they'd run out of parachutes, he boldly opted to go up without one. Because, he said, "Who ever heard of one of these things falling?" Twenty minutes later, it was burning.

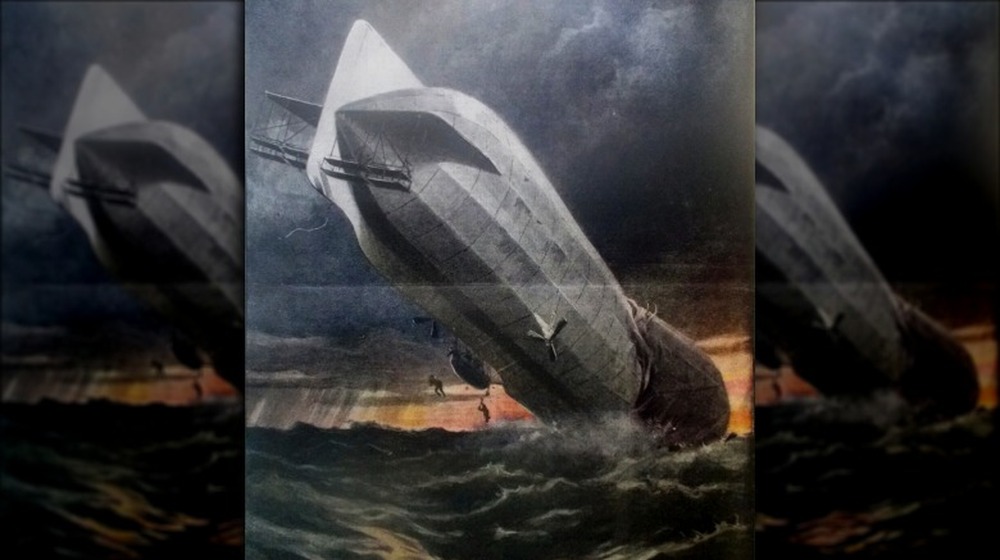

The last, ill-fated flight of the Dixmude

According to the Aviation Safety Network, the Dixmude was built with hostile intentions: constructed during the final years of World War I, the idea behind the German craft was that it was going to be dispatched on bombing runs over New York City. That never happened, and after it was surrendered to the French, it spent several years on the ground.

It wasn't until 1923 that the Dixmude was ready to fly, and she headed to the Saharan oasis town of I-n-Salah. She did make it there — dropping off a mail bag as she cruised over — but the Dixmude and the 52 people on board never made it to their next planned stop. Scattered reports suggested she had been caught in a storm and pushed off-course, and what happened was almost successfully covered up by the French government... until a few fishermen pulled the body of airship commander Lieutenant Jean du Plessis de Grenédan out of the water near Sicily.

According to The Guardian, the commander's death was confirmed by Italian authorities, which made the French backtrack a bit on the story they'd been telling. The Dixmude had not, after all, been sighted heading inland over Africa, and instead, it eventually came out that a group of Sicilian railway workers had seen the final moments of the airship. They — and a local hunter — had seen lightning on the horizon, along with a burning cloud and falling debris that was all that remained of the Dixmude.

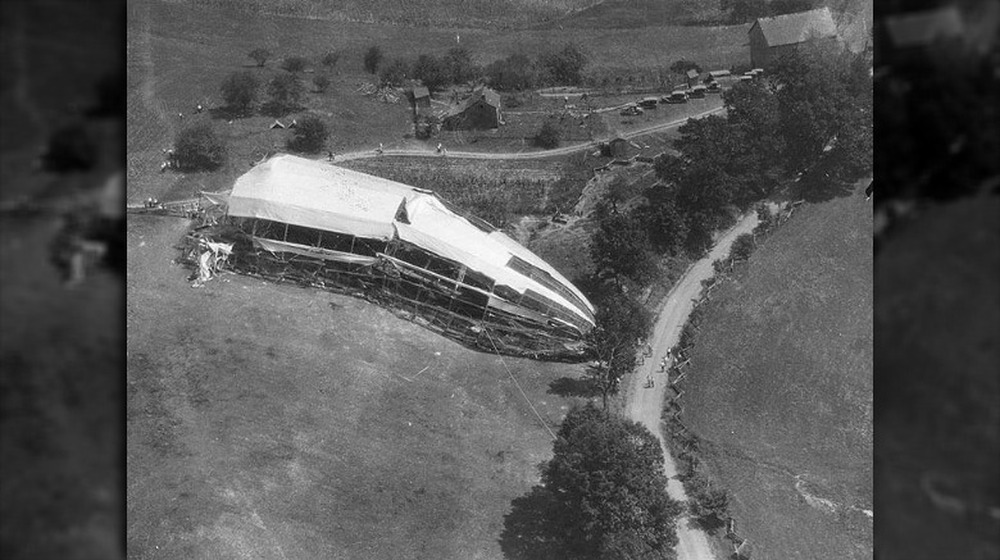

The crash that killed the airship's most vocal supporter

When the R101 crashed in 1930, it killed 48 people — including one man who, had he survived, may have changed the course of airship history. That was Lord Thomson of Cardington, and according to the BBC, he was one of the most vocal proponents of the development of airship technology. The R101 in question was built in Cardington, and NASA says that Lord Thomson had been so sure of the airship's success that he'd thrown his all into promoting the craft as the next greatest advancement in aeronautics.

Not everything went according to plan, though, and in spite of a slew of technological advancements used in the construction of the R101, the airship's maiden voyage ended in flames.

They left England and headed to France on the first leg of what was supposed to be a slow, luxury cruise to India, and the difficulty the ship had with winds was very quickly clear. After recovering from one dive, the crew was unable to recover from a second: after an initial crash (which survivors recounted as being about as peaceful and uneventful as an airship crash could possibly be), the twisted structure pushed one of the engines into the hydrogen-filled balloon, which erupted in flames. There were only five survivors.

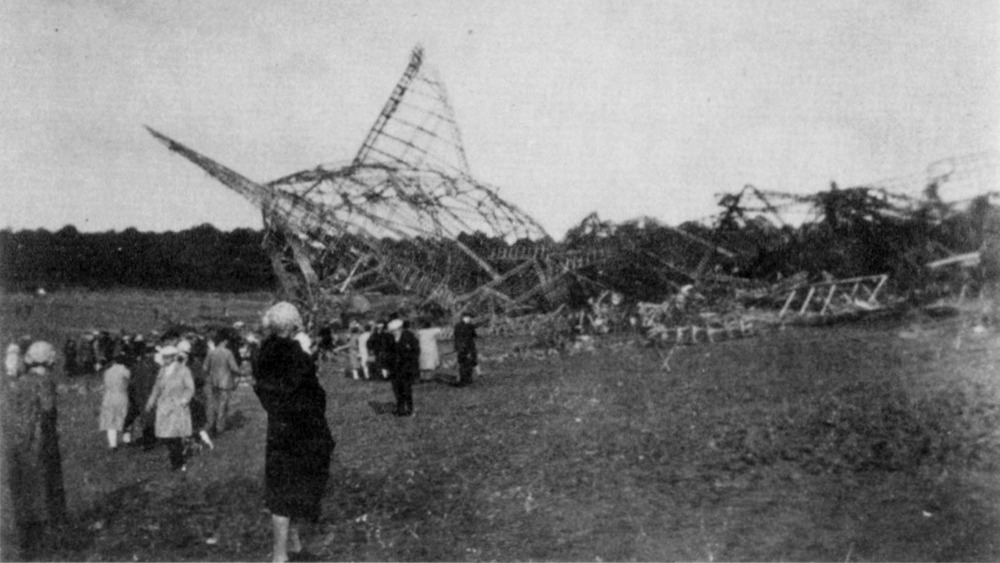

The crash — and mass looting — of the Shenandoah

When the USS Shenandoah was built, it was groundbreaking. Ohio Magazine says that the airship was 680 feet long — almost the length of two football fields — and the nation's first helium-filled, rigid airship. Seeing it must have been awe-inspiring, and it was in the process of being shown to the nation when it was destroyed in the skies over Ohio.

The airship was on an 11-state tour when, on Sept. 3, 1925, it stumbled into a weather phenomenon known as a line squall. Heavy winds lifted the airship even higher, twisting the craft, shattering the structure, and tossing the so-called "Daughter of the Stars" back to earth, where pieces of the wreckage were scattered over Noble County, Ohio.

Reaction to the crash that killed 14 of the 43 people on board wasn't Ohio's proudest moment. Even as the owner of the land where the airship crashed started charging lookie-loos to come onto his property, souvenir-hunters — led by local residents — descended on the crash site in numbers that ultimately led to soldiers from a nearby military base being called out to try to protect the crash site. By that time, the Associated Press reported, "Cables, platforms, joints, gasoline tanks, electric communications wires — everything detachable was gone."

In 2020, the Smithsonian reported that pieces of the Shenandoah were still being recovered, thanks largely to the efforts of Theresa Rayner and her work collecting artifacts for her travelling museum.

Disaster but an incident

"Disaster but an incident" was how the New York Times reported Germany was interpreting the loss of their L-1 airship... in a "It's just a flesh wound!" sort of way.

And that's saying a lot for Germany's faith in the whole idea of the airship. When the L-1 crashed in the North Sea in 1913, it became the eighth airship lost to weather-related causes in just seven years. The experts — presumably, those not on the craft and with no intentions of ever getting on one — publicly described the accidents as "kinderkrankheiten," which is a very German word summing up the difficulties that come with experimenting with new technology. So, what exactly happened in the North Sea?

The Times also reported that just five days before Germany's promise not to abandon the idea of airships, the L-1 had been cruising somewhere above 4,000 feet when a combination of a loss of gas (caused by the cold) and cargo that was just too heavy made her a sitting duck for a storm — and that's why what happened. Her crew had just enough time to radio for help before getting caught in a hurricane, which smashed her into the sea. Of the crew, seven were plucked from the icy waters while 15 more — including the airship's commander — were almost immediately declared dead.

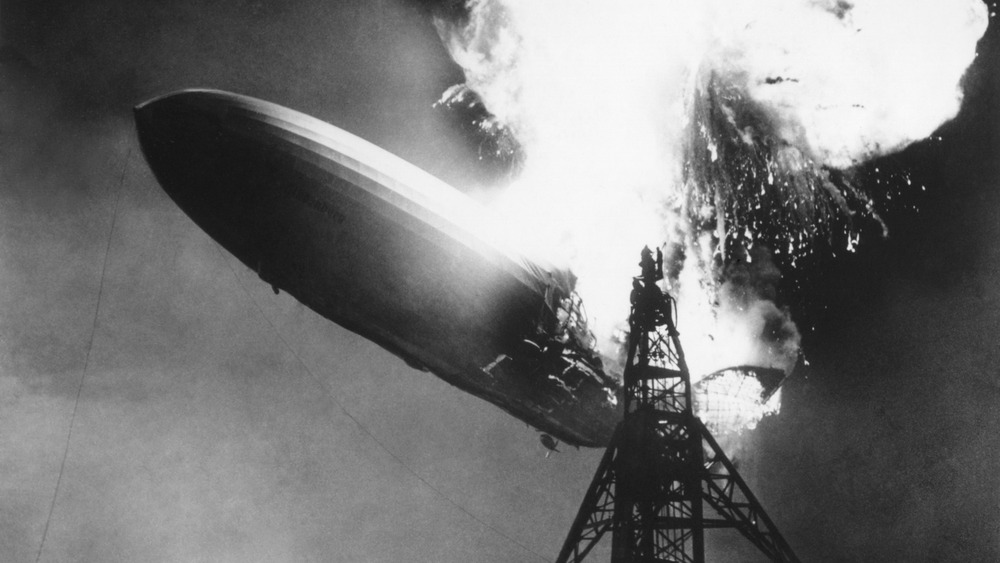

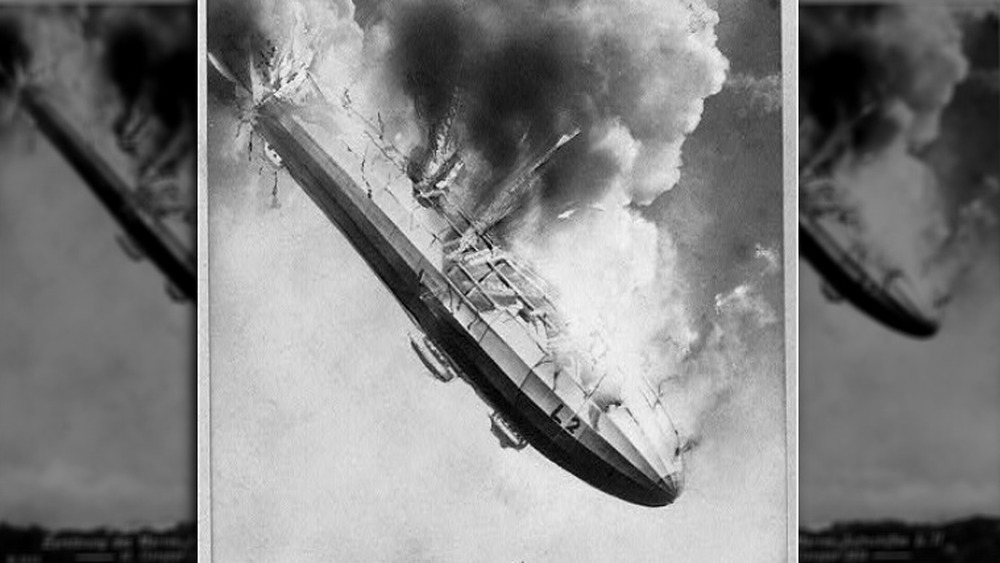

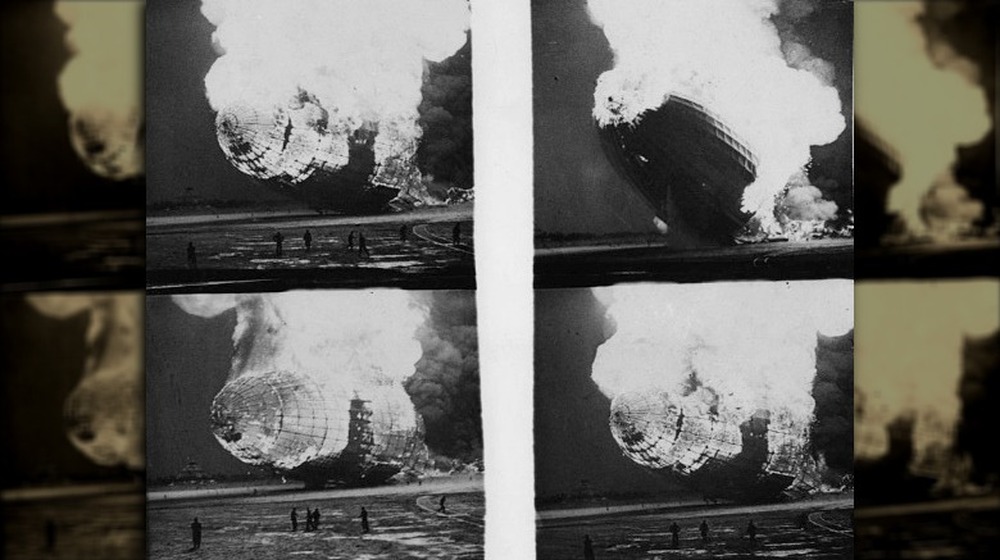

The most famous airship disaster of all

It's the Hindenburg that's the most famous of all airship disasters, but strangely, it was less deadly than many might suspect. There were 97 people on board the airship when things started to go very literally sideways and downward, and 62 survived. According to LiveScience, it's the Hindenburg crash that's so infamous because it was the "first massive technological disaster caught on film," and that means the death throes of the airship have been viewed — in real time — by millions. Still, there's questions about exactly what happened.

The Hindenburg had left Germany on May 3, 1937, and cruised into New Jersey just three days later. The crew maneuvered into a mooring position, dropped the lines, and that's when the ship's fabric hull started to flutter and the fire started near the tail. The fire spread so fast that it lasted just 34 seconds, leading to one reporter's outburst: "Oh, the humanity!"

It's generally accepted that the fire started thanks to a mix of oxygen and escaping hydrogen, but the Smithsonian agrees that what caused the fire is still debated. The long-running theories of sabotage have fallen out of favor, and current favorites are that the fire was sparked by an unfortunate build-up of static electricity or St. Elmo's fire, which happens when static jumps between the air and an object. Whatever really happened, it was the end of the airship era.