The Spy Ring That Helped George Washington Win The American Revolution

When schoolchildren in the United States first learn about the American Revolution, they're typically given a simplified version of the story. The colonists got mad about various British incursions, rebelled, and started a new country. Simple enough for a child to understand, right? Yet, as we grow older, many learn that the American Revolution was more uncertain. For George Washington, then the commander of the Continental Army, winning the war was no easy task. According to Mount Vernon, American forces were chronically underfed, underfunded, and in danger of simply losing it all.

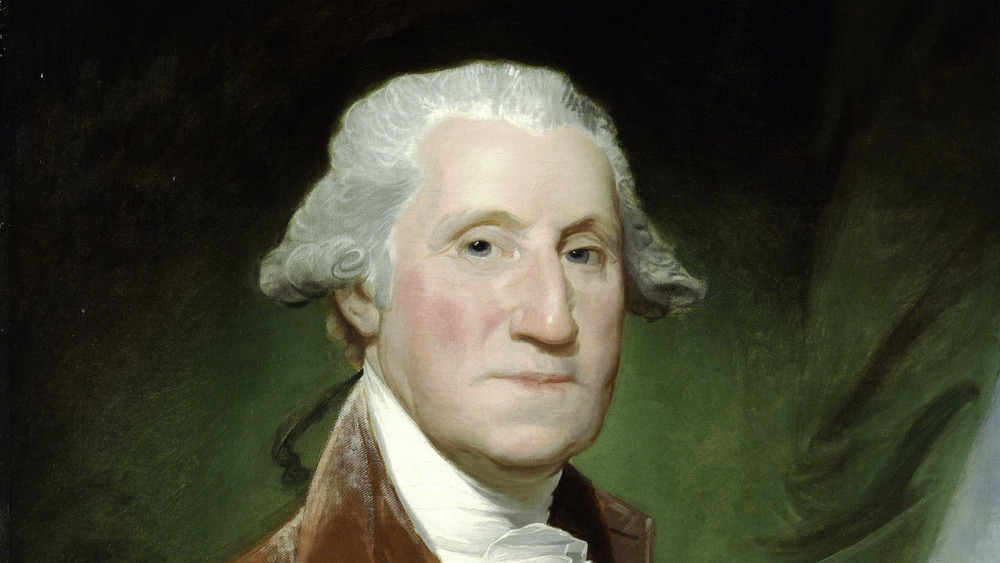

This meant that Washington and his supporters had to draw on everything they had at their disposal. While this sometimes meant cinematic battles, other key components of the war-winning toolkit were harder to expose. That was very much on purpose, for George Washington was not only a general and future president — he was also a spymaster.

Throughout the war, patriots used a series of spies to gain valuable intelligence on British forces. Arguably one of the most important aspects of this espionage effort was the Culper Spy Ring. Operating in and just on the edges of British-controlled New York, the members of the spy ring ferried incredibly valuable information out of the city and into Washington's hands. These spies were so good, in fact, that very few people knew about them, even well into the present day. This is the spy ring that helped George Washington win the American Revolution.

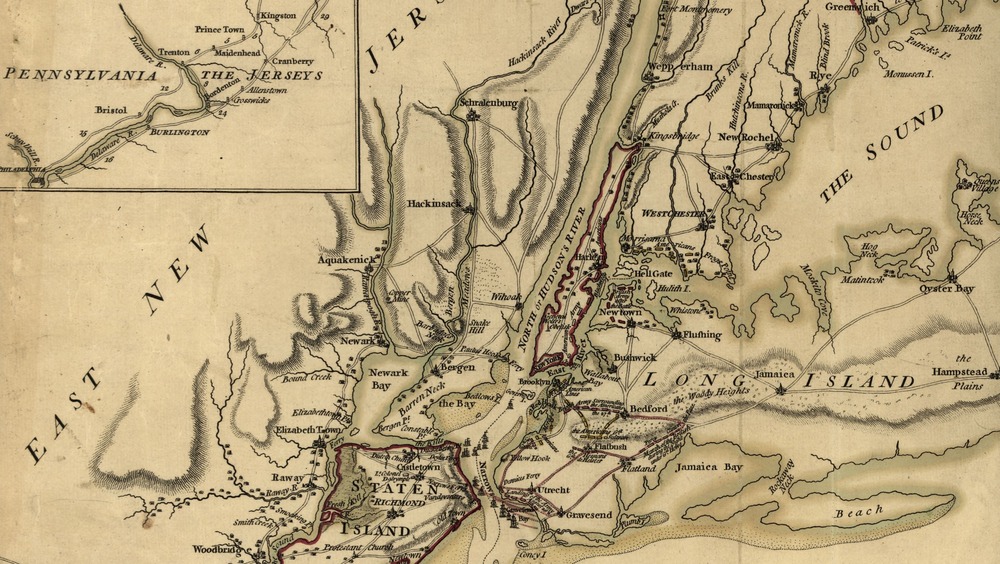

The Culper Spy Ring began on Long Island

In 1778, New York City was controlled by British forces who were attempting to stamp down the revolution started by those colonial troublemakers. Yet, while officers on both sides were maneuvering troops and supplies into place and clashing in battles, much of the real work of war was done quietly. There were spies in New York City.

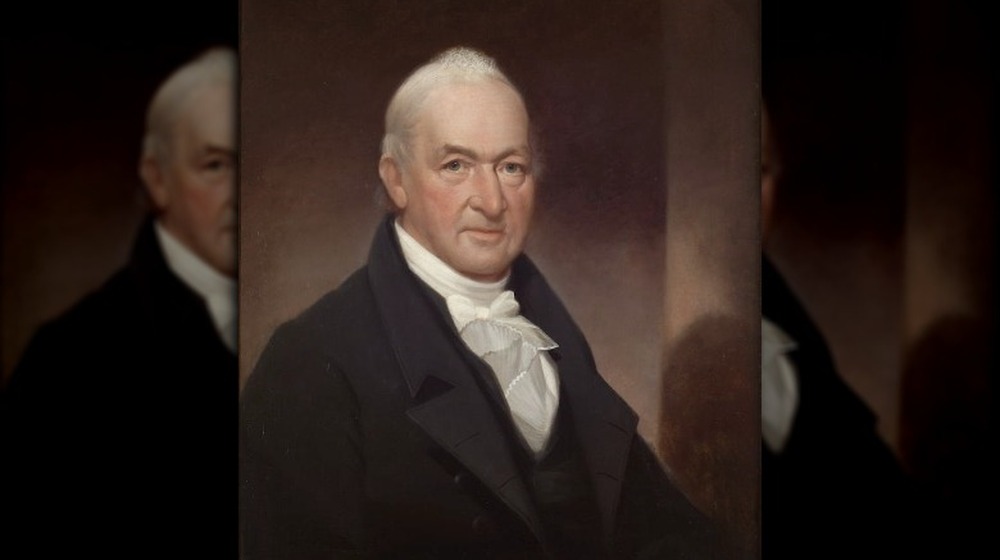

The Culper Spy Ring operated from 1778 to 1783, according to Britannica. Its members included military officer and organizer Benjamin Tallmadge, farmer Abraham Woodhull and merchant Robert Townsend, who went by the code names Culper and Culper, Jr. respectively. Other agents included tailor Hercules Mulligan, Anna Strong, and boat captain Caleb Brewster. Generally, spies would collect information in and around New York City, then relay it to agents on Long Island, who ferried documents across the Long Island Sound and towards George Washington's position.

According to The New York Times, historians weren't even really sure that there had been a network of spies until the 1930s. It seemed likely, given how strategic Long Island and its resources were to British troops, though it wasn't really under their control. Yet, it took well over a century before anyone could be sure it had all happened. That is, unless they were one of the spies themselves.

Some key spies existed before the Culper Spy Ring was formed

Espionage was already part of a war's landscape long before the members of the Culper Spy Ring formed their association. According to the International Spy Museum, people were discussing espionage tactics as early as Sun Tzu's The Art of War, written more than 2,500 years ago.

Agents were already feeding information to Washington's forces before the more complex spy ring formed on Long Island. These included Hercules Mulligan, a New York City-based tailor who used his position to spy on the British occupying the city. According to ThoughtCo, Mulligan used his tailor shop, which catered to British officers, to listen in on sensitive conversations about supplies, troops, and the odd plot to kidnap George Washington. All told, Mulligan supplied information that saved Washington's life on at least two occasions, and provided valuable intel about British forces.

An enslaved man named James Lafayette Armistead even acted as a double agent in Virginia, reports History. He insinuated himself in a British military outpost and began to provide information to officers there, making it seem as if he were friendly to their cause. Armistead told the Marquis de Lafayette, commander of the French forces aiding the Americans, vital intelligence about British troops surrounding Yorktown, Virginia. Using this intel, Washington was able to prepare for and ultimately win the Battle of Yorktown, which then ended the American Revolution.

Spies who were caught faced deadly consequences

Regardless of the time, place, or cause, being a spy has often been a deadly business. Over the course of the American Revolution, agents from both sides were caught and executed. For the agents of the Culper Spy Ring, this must have added to the intensity of their work. Being revealed could mean no less than a trip to the gallows for everyone involved.

That's certainly what happened to Nathan Hale, the young Continental Army captain who volunteered to collect intelligence on Long Island in 1776. According to History, he was successful for a few weeks, then was caught as he was attempting to sail back into American territory across the Long Island Sound. Though it's still not clear why the British targeted Hale specifically, he was found guilty of espionage and hanged on September 22, 1776.

It wasn't easier for British spies, either. Per the American Battlefield Trust, Major John André was executed for the same charges as Hale. André was head of the British Secret Service and the liaison for Benedict Arnold, the American military officer who infamously betrayed Washington's forces. Though Arnold and his wife would escape to England, André was caught with incriminating documents that indicated he and Arnold had colluded to hand the key stronghold of West Point over to the British. After a short trial, André was hanged on October 2, 1780.

George Washington recognized that intelligence was key to winning the Revolutionary War

With the precedent set by spies throughout history, not to mention an underfunded and largely amateur army, Washington realized that he couldn't rely on classic battlefield tactics to win the war. His use of espionage showed that he had a canny, opportunistic side that recognized the changing face of war.

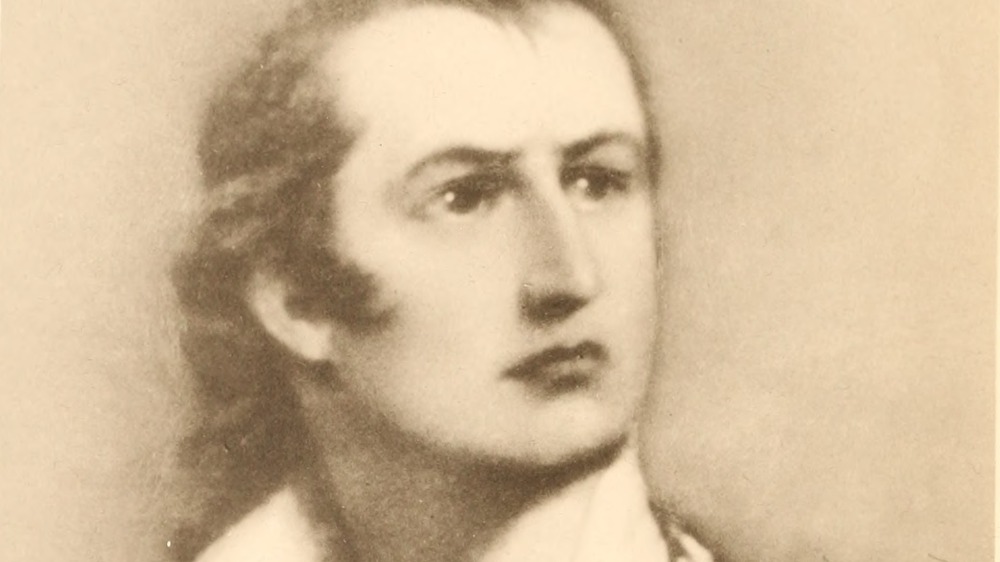

According to Mount Vernon, Washington himself had a code name in the Culper Spy Ring. He was simply agent 711. Yet, the plain designation underlies Washington's true role as a spymaster in charge of a complicated network of espionage agents. It all began with Benjamin Tallmadge, the military officer who Washington put in charge of the brand-new nation's military intelligence. Tallmadge was the key to it all, if only the British knew. He recruited people he knew and trusted on Long Island, forming the basis of the Culper Spy Ring.

Tallmadge wasn't the first spy set to task by George Washington himself. History reports that, besides the unfortunate case of executed spy Nathan Hale, other spies assisted the first commander in chief. Continental Army soldier Thomas Knowlton organized the rather large group of "Knowlton's Rangers," who arguably acted more as scouts than spies, but who nonetheless established a precedent for gathering military intelligence during the war. Only two years after Knowlton died in the 1776 battle of Harlem Heights, the Culper Spy Ring would be formed by Tallmadge and Washington working together.

The Culper Spy Ring used new espionage tactics to evade capture

The Culper Spy Ring used a mix of old-fashioned spycraft and some then-new technological advances to do their work.

Previously, as Britannica reports, many spies were single people who went behind enemy lines to gather information. Since that worked out pretty poorly for people who were caught, like Nathan Hale, the Culper Ring was instead a small group of people working around the edges of British-controlled territory. As long as they could stay undercover and keep the trust of British officers and other military agents, the stability of the spy ring could prove to be very valuable.

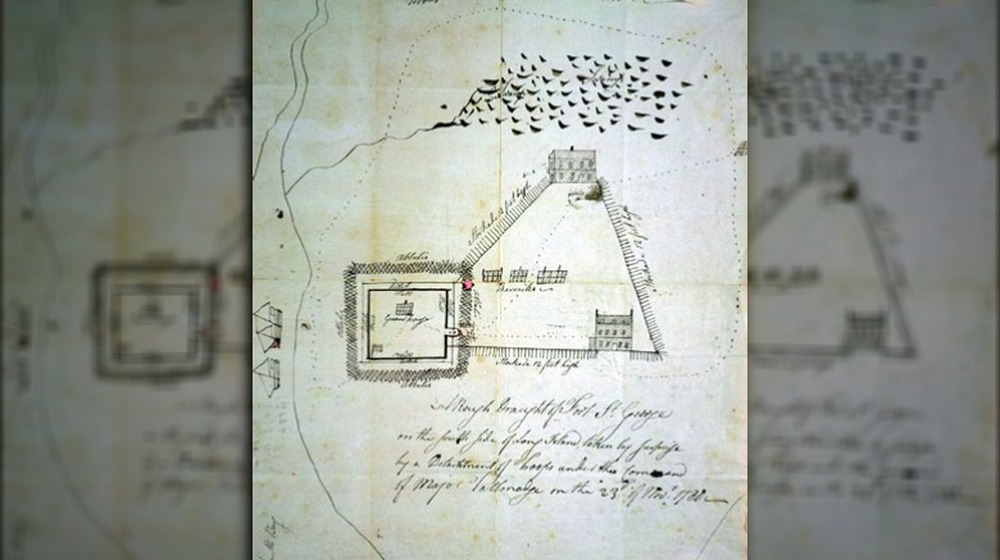

Over the course of their work, the Culper Ring produced information on British troop movements, their supply levels, naval maneuvers, and even sketches of military installations that could be useful to Washington and the Continental Army. To get that intel safely into Washington's hands meant some new advances. According to Mount Vernon, that included ultra-advanced invisible ink that resisted traditional detection methods. Messages could be written between the lines of a seemingly boring letter, and may have also been secreted in pamphlets, books, or even blank pages of an account ledger. James Jay, brother of future first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Jay, supplied the ink ingredients from his home in England.

Even George Washington didn't know who all of the spies were

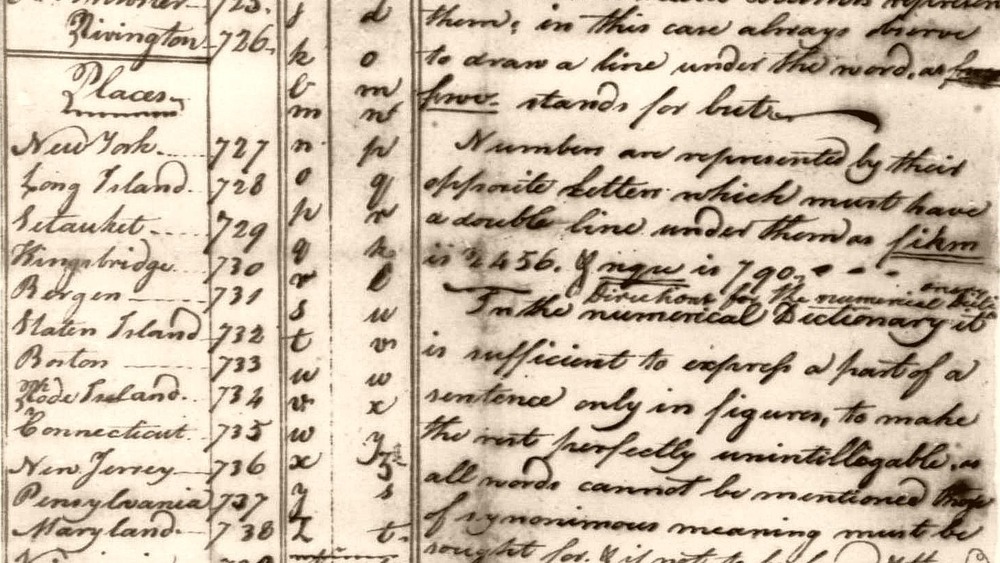

One of the most vital and frankly obvious parts of a spy's toolkit is secrecy. Of course, if everything is out in the open, the intelligence is no good and spies can face detainment and even death in the more dire situations. To this end, says Mount Vernon, identifying information in the Culper Spy Ring was kept fragmented and secret, to the point where even Washington wasn't totally sure who was in his own espionage network. The Culper Ring's cipher, which relied on numbers to refer to people and places, helped conceal the true nature of their information.

It's even possible that, as George Washington's Secret Six suggests, Washington may have unknowingly met members of his own espionage network while on a 1790 trip to New York. Certainly, Robert Townsend never revealed himself, even though Washington apparently tried to contact the mysterious "Culper Junior."

Perhaps Washington understood "Culper Junior's" reluctance, even after the war had ended. During the Revolution, this secrecy was doubly important, as captured spies would be less able to reveal everyone, even under duress. It also preserved some of the spies' key positions near British sources like military officers who thought they could talk freely. As Ozy argues, that's likely why we still don't know the identity of some agents, including female informants who would likely have been ignored by careless officers as they listened in on what should have been clandestine conversations.

The Culper Spy Ring used an elaborate cipher to communicate

Benjamin Tallmadge, an army major who helped start the Culper Spy Ring, developed a number of communication methods meant to confuse anyone who intercepted the ring's messages. These included cutting-edge invisible ink technology and code names for the ring's members. However, one of the most complex and compelling developments of the Culper Spy Ring was Tallmadge's use of a number-based cipher.

That cipher, according to Mount Vernon, included over 700 numerical codes that were outlined in a code book. The numbers could refer to places, people, objects, and even vague parts of speech like pronouns and adjectives. Without the code book, anyone who intercepted a letter written in the cipher would have been incredibly frustrated upon attempting to figure out just what was written in front of them.

While we're still not totally sure of the exact techniques the Culper Ring used to hide letters, they likely included at least some of the variety described by Mount Vernon. These strategies could be as simple as rolling up a piece of paper and jamming it into a quill or button, to using paper cutouts to reveal hidden messages in the middle of a seemingly innocuous letter.

Without the Culper Spy Ring, Washington may have lost the Revolutionary War

As much as the activities of the Culper Ring may sound like the overblown plot to a movie or pulpy novel, they were actually key to securing strategic advantages for the Continental Army over the course of the war. In fact, without the help of the Culper Spy Ring and other espionage efforts, it's very possible that Washington would have lost the war, dramatically changing the course of American history.

In 1780, ThoughtCo reports, the spy ring warned Washington of British plans to take over Rhode Island, which would have seriously hurt the efforts of America's French allies there, commanded by the Marquis de Lafayette and the Comte de Rochambeau. The Continental Army was able to move its own forces into the area as a show of strength, and therefore warded off the offensive.

The Culper Spy Ring also uncovered a British plot to create counterfeit money. While this may seem like a small affair in the grand scheme of war, with its deadly battles on sea and land, a successful counterfeiting plot could have seriously destabilized the rebel effort. According to the Journal of the American Revolution, if both the economy and peoples' faith in the newborn government was sufficiently shaken, then many colonials might have turned Loyalist and supported the British. The Culper Ring's intelligence on the affair appears to have uncovered the plot early enough to keep it from growing out of control.

Anna Strong used petticoats to communicate with her fellow spies

The Culper Spy Ring included what appears to be multiple female agents, including one named Anna Smith Strong. Though she seemed to be a housewife, ThoughtCo reports that she had a strong motivation to join the ring. Her husband, Selah, was a judge who had been arrested on charges of sedition and thrown onto a British prison ship, leaving Anna and the children on their own.

According to the National Women's History Museum, Strong was, conveniently enough, the next-door neighbor of farmer Abraham Woodhull. Information gathered in New York City made its way to Woodhull and then Strong, who then had to get messages to fellow spy Caleb Brewster. To signal to Brewster that information was ready to pick up, Strong communicated via clothesline, which Brewster could see from his ship. A black petticoat meant that a message needed to be picked up. Handkerchiefs hung alongside the petticoat corresponded to one of six prearranged pickup locations.

It was, quite frankly, a brilliant system that used mundane woman's work to conceal a key point in an espionage network. Given that Strong's system was never revealed during the war, it's clear that anyone who saw her hanging a black petticoat on the clothesline assumed only that she was doing the laundry and never paid her any mind.

One agent of the Culper Spy Ring still hasn't been named

While we know the identities of some of the people involved in the Culper Spy Ring, not everyone who assisted Tallmadge and his associates in their espionage work has been named. Few have captured imaginations more than the mysterious Agent 355. That's in part because, according to the Culper cipher, Agent 355 was almost certainly a woman.

According to the National Women's History Museum, "355" was code for "lady." The woman in question was likely selected by Abraham Woodhull and lived somewhere on Long Island. Some believe she was part of a Loyalist family that would have given her almost unlimited access to British leaders like intelligence officer Major John André and Benedict Arnold, the Continental Army officer turned traitor. Others rather romantically embellish the tale, going so far as to say that this mysterious woman was in a relationship with fellow spy Robert Townsend.

According to Ozy, other historians think she may have simply been Anna Smith Strong, who may have had access to the social events where 355 is thought to have mingled with British officers. Yet, some sources hint that she was captured by the British and died on a prison ship in 1780. Ultimately, we can be pretty sure that Agent 355 existed and fed information to the Culper Spy Ring, but anything more beyond that is still concealed, more than two centuries after her death.

The spy ring uncovered Benedict Arnold's dealings

Perhaps one of the biggest scandals of the war was the affair of Benedict Arnold. While the intervening generations have simplified the story into one of dastardly villainy and greed, Smithsonian Magazine argues that the real story of Arnold and his defection to the British is more complex. Originally a passionate supporter of the revolution, Arnold became a prominent figure in Washington's Continental Army. Yet, it was apparently a combination of money struggles and lack of recognition that pushed the brash Arnold to betray the cause he had once so vocally upheld.

Arnold began to communicate with Major John André to turn over West Point, a strategic military garrison in New York. Then, the spies got involved. Someone intercepted the messages sent between the two men and gave them over to the Culper Spy Ring, History reports. This led to the capture and eventual execution of André, though Arnold became a British officer and eventually fled to England as Americans learned to hate him. Meanwhile, West Point remained in American hands, all thanks to the work of the Culper Ring.

No one in the Culper Spy Ring was ever caught

One of the most outstanding achievements of the Culper Spy Ring is surely the fact that none of the spies involved in this complicated arrangement of locations and people were ever uncovered. Throughout the course of the American Revolution, they remained successfully undercover, even while operating in the heart of a British-occupied New York City.

After the war, everyone in the spy ring pretty much returned to their regular lives, as ThoughtCo reports. Abraham Woodhull kept farming on Long Island and eventually became a fixture of the local legal system as the first Suffolk County judge. Anna Strong's husband, Selah, was released and rejoined his family. Benjamin Tallmadge, the ring's organizer, became a banker, postmaster, and, eventually, 17-year member of the U.S. Congress. Caleb Brewster, the captain who ferried messages across Long Island Sound and safely away from British territory, worked a variety of jobs after the Revolution, including a return to espionage during the War of 1812.

And though Robert Townsend was rumored to have carried on an affair with the mysterious Agent 355, he never legally married and lived with his sister in New York until he died in 1838. Townsend may have been one of the most close-lipped members of the Culper Spy Ring, as no one but his fellow spies knew of his involvement until a historian uncovered Townsend's role in 1930.