The Horrifying True Story Of Ed Gein

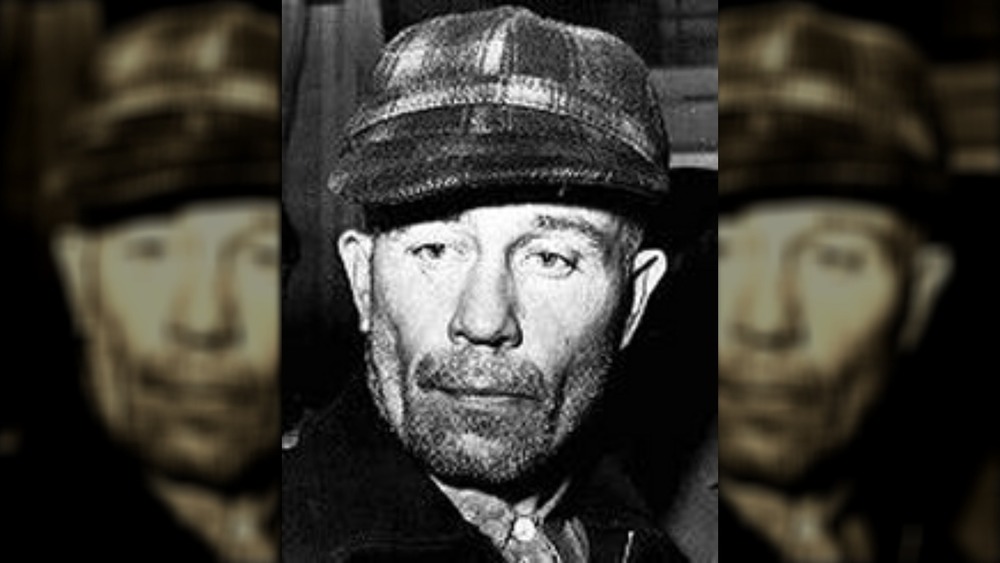

When it comes to the most terrifying figures of the true crime genre, there's a handful of people that immediately come to mind. Charles Manson. Ted Bundy. John Wayne Gacy. Their crimes — and their lives — are the stuff of widespread fascination, because there's something in all of us that just wants to know how someone could do these horrible things. And then, there's Ed Gein.

Since his arrest in the late 1950s, Ed Gein has not only become known as the inspiration for some of the movie world's darkest characters — most notably Psycho's Norman Bates — but he's ended up in a class all his own. The man known as The Butcher of Plainfield has become synonymous with murder, cannibalism, and necrophilia — an unholy trinity of serial killing that's so dark, it's almost impossible to imagine. The skin suit he made from dead women is the stuff of legend, only ... this legend is true.

But that brings up an important question. What, exactly, is the truth of Ed Gein and his crimes? Surprisingly, it's not what most might think it is.

It started at a hardware store

When it comes to the capture of Ed Gein, it's a little different than the typical arrest story. There was no trail of victims like the ones left behind by Jack the Ripper, and Gein's fall started with a trip to the hardware store to pick up some antifreeze.

It was Nov. 16, 1957, when Gein stopped by the local Plainfield, Wisc., hardware store and that, says the Hanneman Archive, is also when he shot and killed the store owner, Bernice Worden. In his later testimony (via Edward Gein), Gein would later claim that he didn't remember the series of events that happened at the hardware store, in part because of a massive aversion to the sight of blood. It was sheriff's deputies who later determined that he had first shot Worden before slitting her throat and taking her home.

Gein, they say, was an immediate suspect when Worden turned up missing. He'd been seen around town at the time of the murder, and deputies went to his 160-acre farm on two separate occasions immediately in the wake of her disappearance. The first time he wasn't there, and the second ... well, that's when they looked in a nearby shed that doubled as a kitchen.

And that's when they saw her. It was the first day of hunting season, but it wasn't a deer that had been gutted and hung in the shed — it was Worden.

Here's what police found

Bernice Worden's body had been prepared in much the same way a hunter would prepare a deer, and it didn't take long for law enforcement to realize there was much more hidden behind the doors of the unassuming farmhouse.

Precise details of exactly what investigators found can vary by the telling, but according to the New Zealand Herald, it's agreed that there were scores of grisly trophies. Among them were household items he had fashioned from human skin, including a garbage can, four chairs with seats replaced with skins, and lampshades made entirely of skin. Skulls had been cut and turned into bowls, other skulls were mounted onto bedposts, and an armchair was made from bones.

There were also a series of death masks, made from hair and skins. (Some accounts say there were nine, others say ten.) There were collections of noses, limbs, and female genitalia, and then, there was the skin suit. That, law enforcement found, consisted of "leggings" and a "vest," both made from tailored skin, along with other "clothing" items, like a belt, purse, and gloves.

Ed Gein would later confess to the murder of two women, Bernice Worden and Mary Hogan. Their remains only made up a very small part of what was found — one of the "death masks" was identified as Hogan, while Worden's head was found in a sack, and her internal organs were in a bucket near her body.

Most of the parts came from his grave-robbing

After police discovered what was really inside Ed Gein's home, he was, of course, arrested. According to the Hanneman Archive, Gein quickly confessed to killing Bernice Worden at her hardware store and to another murder three years prior. He had shot and killed Mary Hogan on Dec. 8, 1954, but that, he said, was all the killing he'd done. So, where did all his grisly artifacts come from?

Gein told law enforcement that between 1947 and 1952, he had made regular visits to three local cemeteries — Plainfield, Hancock, and Spiritland. He claimed to have done it while hardly remembering what he was doing, and said (via Crime + Investigation) that he had fallen into a pattern of scanning newspaper obituaries for his "type" — middle-aged to older women, preferably ones he'd known in life.

Then, with the help of a gravedigger only known as "Gus," he'd head out to the cemeteries, exhume the bodies, and collect whatever struck his fancy. Sometimes he reburied the body untouched, sometimes he took the entire thing, and sometimes, he took pieces. He only killed, he claimed, when Gus was committed to a home.

Law enforcement was skeptical but began exhuming some of the graves he claimed to have visited. When they found several empty graves and others with artifacts — like jewelry and dentures — outside of the caskets, they confirmed the source of his body parts.

Technically, Ed Gein might not be a serial killer

Ed Gein is very commonly called a serial killer, but it's entirely possible that's not at all accurate. The term "serial killer," says Psychology Today, has a very concrete definition. In order for someone to be considered a serial killer, they need to have committed "at least three murders over more than a month with an emotional cooling off period in between."

That definition isn't without problems, but given that Gein only confessed to — and has been concretely linked to — just two murders, it's entirely possible that defining him as a serial killer is incorrect. According to History, the majority of the remains of the women found in his home came from his late-night grave robbing, and here's where things get complicated.

The Hanneman Archive says that some of the body parts recovered from Gein's house belonged to 8-year-old Georgia Jean Weckler and 15-year-old Evelyn Hartley, who disappeared — respectively — in 1947 and 1953. It was never discovered what happened to them, but Gein was never concretely connected to their disappearances, either. Gein was also rumored to have had something to do with two men who disappeared from Plainfield after being seen at a local tavern, but here's the thing — none of those four victims have anything in common with Gein's true obsession — his mother.

The community had no idea

Ed Gein's parents, Augusta and George Gein, married in 1900, and when Ed was 8 years old (and older brother Henry was 13) — around 1915 — they moved to the farmhouse where his grisly artifacts would later be discovered. Locals had known him for a long time, and until the day of his arrest, they'd sort of liked him. He made his living by doing odd jobs for people, and according to the New Zealand Herald, he was frequently described as "odd, but polite and dependable" and noted that the "community trusted the brothers and regarded them as reliable."

While Ed was regularly picked on while he was in school — in part thanks to a speech impediment, a lazy eye, and social awkwardness — he spent much of his life doing a lot of jobs for a lot of people around town, a role that increased after the death of his father in 1940. That was everything from hanging windows to painting homes and doing repair work, but that's not all he did — his services as a babysitter were also in high demand in the community. He got along decently with many people. In fact, he had been having dinner with a neighbor family when law enforcement came calling (via Time). So, what happened?

The woman behind Ed Gein

The Hanneman Archive says that it was something of a perfect storm that came together to create Ed Gein. Diagnosed as schizophrenic, Gein also suffered from an unhealthy attachment to and obsession with his mother — and when she died in 1945, he simply couldn't cope.

The son that Augusta Gein left behind was already severely damaged by years and years of abuse that, according to the New Zealand Herald, started from his birth in 1906. Augusta became determined that if she had to have sons, they weren't going to grow up like their father, George Gein. He struggled with alcoholism, and while he had a bunch of jobs — including one as an insurance salesman — he couldn't keep any of them. (He also spent some time as a tanner, which was where Ed learned his skin-working skills.) Augusta's religion forbid divorce, and as a devout Old Lutheran, she believed every thought and action was sinful and evil. That was especially true, she would often lecture, of drinking and women.

Ed became obsessed with the idea of becoming a woman like his mother ... and would later make his skin suit in an attempt to do exactly that.

After Augusta died in 1945, she was buried in Plainfield Cemetery. Research done by Radford University says that it was about 18 months later that the loneliness became too much for Ed to bear. Hers was the first body he dug up, and he took her head with him.

It's possible Ed Gein killed his brother

George and Augusta Gein's first son was born in 1902, and according to the New Zealand Herald, Henry Gein was considered the more outgoing and friendly of the two boys. While he was still very much his mother's son as well, things started going a little sideways when he began dating a woman that his mother undoubtedly couldn't have approved of — while she stayed in her own miserable marriage because of devout religious beliefs that said leaving would be an unforgivable sin, her eldest started dating a woman who was not only divorced but who already had two kids.

Ed Gein was actually the woman's go-to babysitter, while things were getting serious between her and his brother. The happy couple was looking at moving in together when Henry began becoming more and more vocal about the weird, co-dependent relationship Ed and Augusta had ... and then, in 1944, Henry died.

At a glance, the story was a simple tragedy — Ed and Henry had been clearing brush when the fire went out of control, Ed lost sight of his brother, and his body was only recovered much later. There's a massive "but" here — no autopsy was done, but before his death, Henry had suffered some head wounds that were — at best — suspicious.

It's possible some of his 'crimes' have been exaggerated

Just as Ed Gein isn't technically labeled a serial killer because of his concrete connection to only two actual murders, it's highly likely his other crimes have been exaggerated, too.

Gein is often connected with necrophilia, which gets translated into a belief that he assaulted the dead. Science Direct says that the definition of necrophilia is much, much broader than that, and research done by Radford University suggests that while he was obsessed with the dead, there was no intimacy involved — because "they smelled too bad," according to Gein himself. His obsession with digging up cadavers and fashioning his skin-suits and furniture still falls under the definition of "necrophilia," but sex with the dead doesn't seem to have been one of his crimes.

Gein is also often labeled a cannibal, but according to Time, this is also incorrect. Gein's goal in stealing body parts — and one entire body — was simply to preserve the body to look at, to touch, and to wear.

Psychology Today says that Gein's case is one of the first in which the media's sensationalism of the case and portrayal of his crimes completely blurred the line between truth and fiction, and they say it "transformed a mentally ill man into a cartoonish vampire and grave robber."

There were times Ed Gein sort of confessed

To those he shared his Plainfield community with, Ed Gein was the weird but harmless guy who lived alone with his mother and never really bothered anyone. But hindsight, they say, is 20/20, and according to Time, there were signs that something was amiss.

Gein was an avid reader, and just as there's absolutely nothing wrong with that, there's also nothing wrong with his genre of choice — true crime. The teetotaling son of an alcoholic never hung out at local bars, but he did frequent the local ice cream shop, where he was fond of talking about recent cases that had made headlines. He was also fond of volunteering insight into the inner workings of the criminals' minds, and weirdly, if the case was close enough to home, he often took credit for it. Oh, how the people laughed.

Even more unsettling, Gein — who was known as Eddie — had actually shown off some of his most grisly trophies. Bob Hill was a neighbor to the Geins, and Ed had even gone as far as to show him some of the heads he'd shrunk. He told people that he had a cousin in the Philippines who had sent him the heads, and it didn't seem to weird them out as much as might be expected — they were the same family he was having dinner with when the remains of Bernice Worden were discovered in his shed.

Ed Gein on trial

Everyone deserves a trial in the American judicial system, and when it came time for Ed Gein to face the system, he did so alongside a lawyer named William Belter. Belter, Biography says, went with the insanity defense, and the court agreed. Gein was sent to the Central State Hospital, and while he was there, he continued working odd jobs around the place.

That was in January of 1958, and the Wisconsin Historical Society says that it was just a few months later — in March — that flyers advertised the auction of all Gein's property, from household items all the way up to the farm itself. Before the auction happened, though, the farmhouse burned to the ground.

Fast forward ten years, and Gein was ruled to be fit to stand trial. He was convicted of a single murder — Bernice Worden's — and it was also confirmed that Central State Hospital was exactly where he belonged. He was sent back, where he quite happily and quietly lived out the following years. Dr. Nicola Davies of the Health Psychology Consultancy says that's not entirely surprising — he was in a confined place with strict rules and a regimented schedule, which was precisely what he had gotten used to while growing up under his mother's thumb.

At the end of the '70s, he was sent to the Mendota Mental Health Institute, where he lived out the rest of his days.

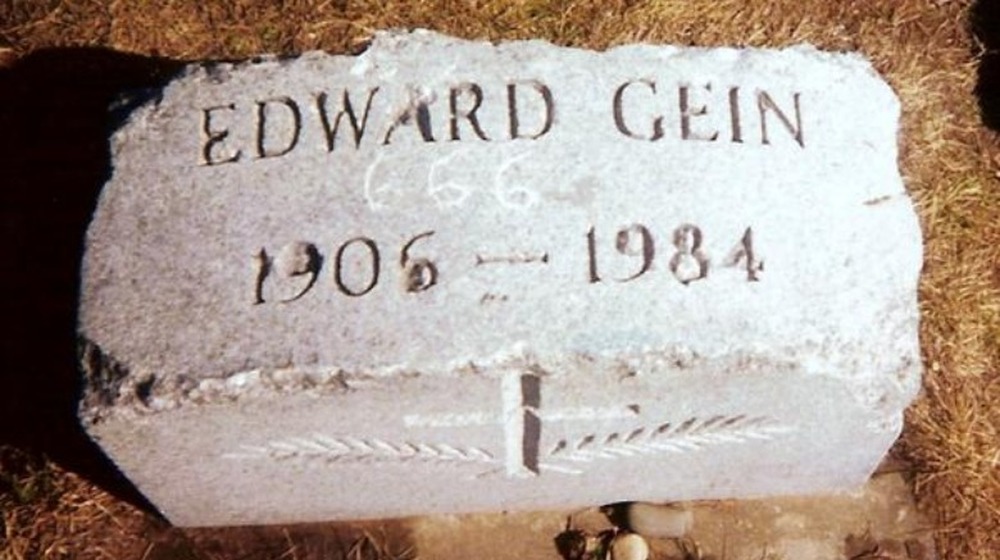

Ed Gein's death and grave

Ed Gein died on July 26, 1984. He was 77 years old, and the official cause of death was "complications from cancer," says History.

That's not entirely the end of his story, though, and strangely, Gein was buried in the same cemetery where he found many of the women he exhumed. The Gein family plot was in Plainfield Cemetery, in Plainfield, Wisc., and according to Atlas Obscura, Gein's final resting place is just a stone's throw from some of the graves he'd dug up. (The Hanneman Archive notes that authorities remain unsure about just how many graves Gein violated, as they didn't exhume everyone in the cemetery.)

Gein is buried between his mother and his brother, but the site is unmarked today. After years of curiosity-seekers chipping off pieces of his headstone, the marker was stolen in 2000. It turned up in Seattle in 2001, and now it's at the Waupaca Museum.

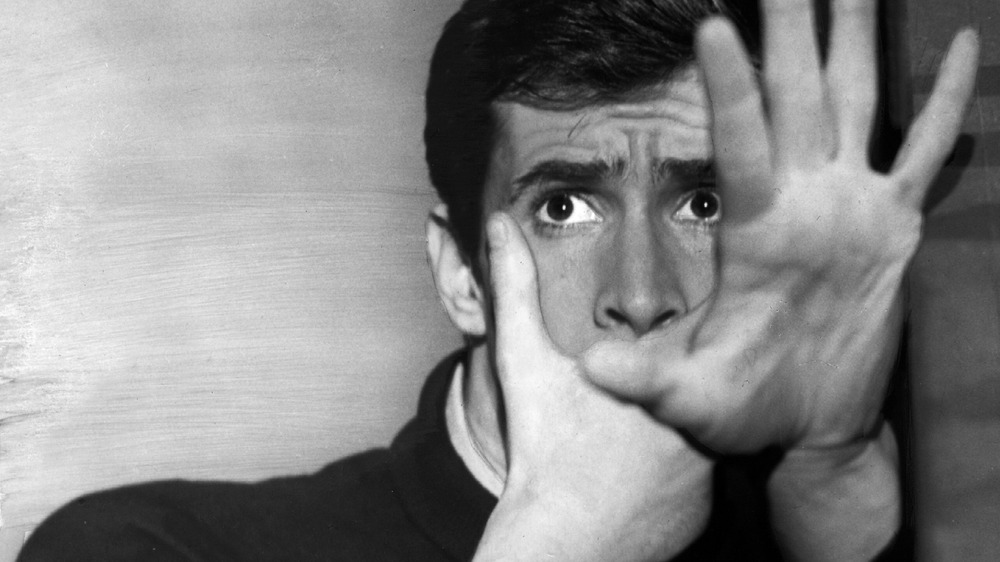

Here are the movies that his life story inspired

Ed Gein's story has been immortalized over and over again in almost mind-numbing number of books, movies, and television shows, but the most famous is undoubtedly Psycho. Written by Robert Bloch and turned into a movie by Alfred Hitchcock, the story of Norman Bates and his mother seem to be plucked directly from the headlines ... only, Bloch — who lived about 30 minutes from Plainfield — has said (via Post Crescent) that it wasn't necessarily his intention.

Bloch wrote in his memoir, "I based my story on the situation rather than any person, living or dead, involved in the Gein affair. I knew ... virtually nothing about Gein himself at the time. It was only some years later ... that I discovered how closely the imaginary character I'd created resembled the real Ed Gein..."

That's not the only movie inspired by Gein, and according to ScreenRant, Hollywood wasted no time. Deranged was released in 1974 — complete with a Gein-like main character — and it's credited with helping spread the necrophilia inaccuracies in the Gein story. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre came out the same year, featuring Leatherface. Then later came Silence of the Lambs, House of 1000 Corpses, The Devil's Rejects, and several films based directly on Gein's story. Biography adds there's also films like Three on a Meathook, the horror comedy Ed and His Dead Mother (with Steve Buscemi as Ed), and Child of God, based on the Cormac McCarthy novel.