This Is The Deadliest Tornado In US History

As of 2021, no tornado has ever exceeded the damage done by the 1925 Tri-State Tornado. In the span of several hours, over 600 people lost their lives and over 2,000 people were injured across three different states in America.

At the time, there was essentially no tornado warning system in the United States. Despite the fact that European meteorologists such as E. Durand-Gréville suggested tornado warning methods, none had been adapted by the time the 1925 tornado hit. In fact, the United States Weather Bureau actually banned the use of the word tornado in weather forecasts.

While the 1925 Tri-State Tornado claimed hundreds of lives, its tragedy inspired local storm watchers who were able to decrease the number of casualties. After the 1925 tornado, local communities started creating tornado warning systems of their own. But unfortunately, it took another 25 years for the United States government to implement an official tornado forecasting and warning system. Until them, people had to listen to euphemisms and wonder how "severe" or "destructive" the storm was really going to be. This is the story of the deadliest tornado in U.S. history.

Forecasting tornadoes without saying tornado

Although some people in the United States who lived in the Midwest were well aware of the existence of tornados, the word itself was off-limits for weather forecasters until the 1950s. According to the National Weather Service, since neither the public nor the Weather Bureau knew much about tornados, "the use of the word 'tornado' in forecasts was at times strongly discouraged and at other times forbidden, because of a fear that mentioning tornadoes may cause panic."

Smithsonian Magazine writes that in the 1880s, some researchers had put together a list of criteria "for conditions that could lead to a tornado," but the government didn't want to cause a panic based on less-than-reliable predictions. So instead, the word itself was banned lest it create a public frenzy. Forecasters were forced to come up with euphemisms like "severe local storms." Meanwhile, as the Weather Bureau went on to create prediction and warning systems for fires, floods, and hurricanes, the Weather Bureau Stations Regulations of 1905 stated that "forecasts of tornadoes are prohibited." In 1915 and 1934, the Weather Bureau upheld the ban.

But despite the Weather Bureau's reluctance to even say the word, tornadoes were known to be an occurrence amongst those who lived in the Midwest. According to Mental Floss, on August 28, 1884 the first photograph of a tornado was captured in what is now South Dakota.

So how does a tornado work?

Although tornadoes have been known to happen around the world, the continental United States experiences the majority of tornadoes. Roughly 40 percent of the eastern continental United States can be considered a tornado region. This area is ripe with tornados due to how tornadoes are created.

According to National Geographic, "tornadoes form when warm, humid air collides with cold, dry air." As the jet stream from the Gulf of Mexico travels up, it hits the cold dry air coming from the north. As the warm air pushes the cold air down, thunderstorms are created. And as the warm air rises, it can cause an updraft, which "will begin to rotate if winds vary sharply in speed or direction." The spinning updraft is known as a mesocyclone, and as it draws more and more warm air in its speed increases. Water droplets from the air create the "funnel cloud" and once that funnel cloud hits the ground, it's a tornado.

On average, a tornado can last as long as a few seconds or a few hours. From F0 to F5, tornadoes are ranked with the Fujita scale based on their intensity "by analyzing the damage the twister has done and then matching that to the wind speeds estimated to produce comparable damage."

The calm before the storm

On March 18, 1925, the weather forecast had been "shower and cooling temperatures." According to Popular Mechanics, this forecast wasn't out of the ordinary, and no one seemed to suspect what was coming. Forecasters hadn't even given the "dreaded allowable forecast 'conditions are favorable for destructive local storms.'"

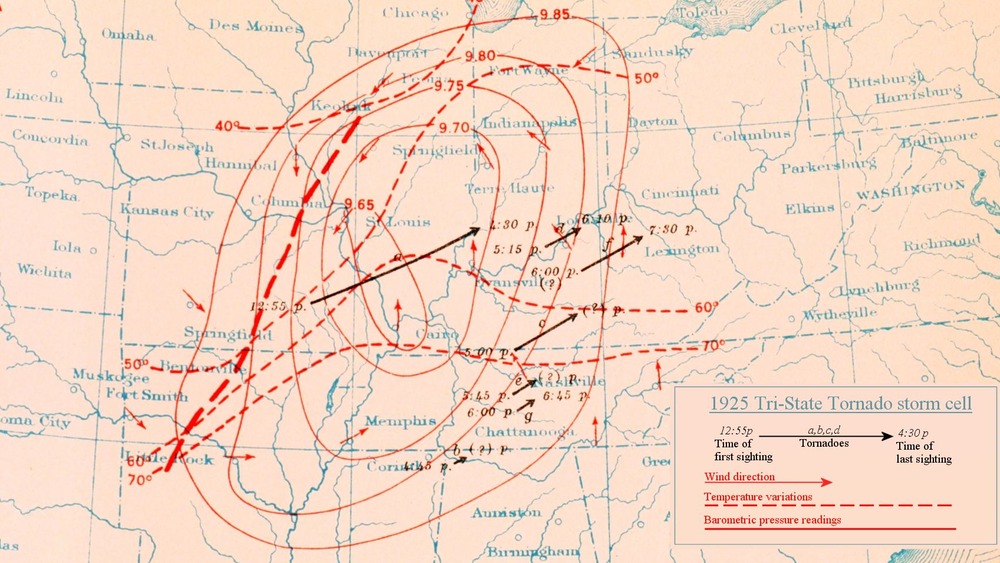

Even though no one was looking at tornado forecasts in particular, the Weather Bureau had noticed a low-pressure system that had traveled from Canada "all the way to the Oklahoma-Texas border before curving back towards southern Missouri." Meanwhile, a warm front from the Gulf of Mexico was moving north and the moist warm air began to mix with the northern air. Temperatures rose steadily that day and even ended up reaching 70°F around Cairo, Illinois by 4 PM. This mixture created what's known as a "lifting mechanism" and before long, the storm began to spiral.

Gray skies that had been sprinkling rain over southeastern Missouri suddenly turned black. In Gorham, Illinois, the storm announced its approach by throwing hail the size of golf balls. Orange Bean Indiana writes that some people recounting "feeling ill at ease as the cloud darkened, expecting a big storm with rain and flooding. No one expected the massive twister." And since the word tornado had been banned by the Weather Bureau, some people in the region didn't even know what a tornado was.

12 deadly tornadoes

Although the Tri-State Tornado is considered the most memorable due to its destructive power, there were actually 11 other tornados that day that roared through the Midwest. They were recorded in Alabama, Kansas, and Kentucky as well, but none of their individual damage could rival that of the Tri-State Tornado.

Five of the tornadoes measured at least an F3 in intensity, and according to the Building Safety Journal, over 250 people were injured and over 50 were killed as a result of the 11 other tornadoes alone. Many people refer to this event as the Tri-State Tornado Outbreak, since the Tri-State Tornado claimed most of the lives that day. And despite the fact that both the outbreak and its most destructive tornado are known as "Tri-State," the damage was much more extensive than just three states. Most of the damage was concentrated in Indiana, Illinois, and Missouri, but Tennessee was also hit as well.

The Tri-State Tornado

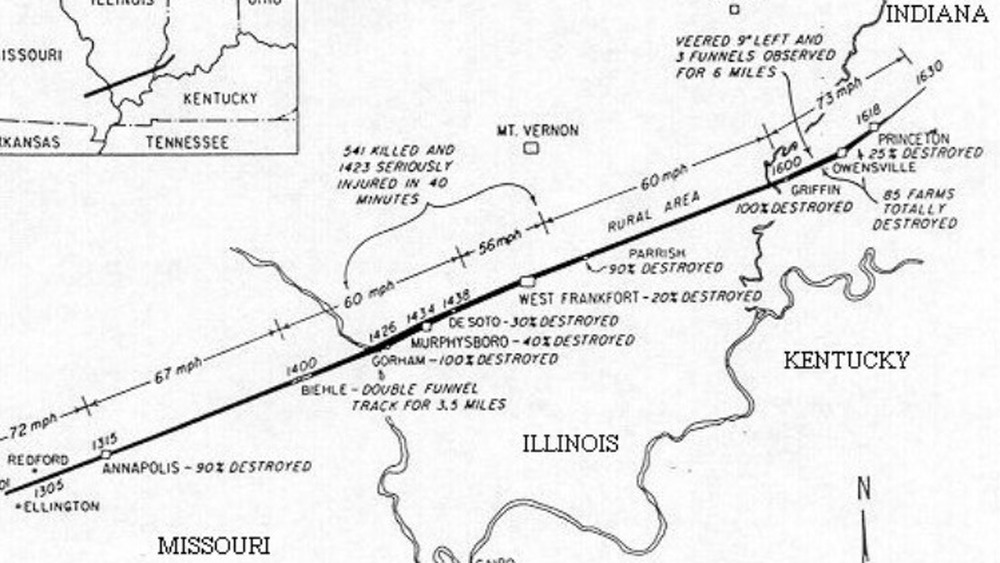

The Tri-State Tornado touched down near Ellington, Missouri. With speeds of 73 mph, the tornado reached Annapolis, Missouri around 1:30 PM. "It came and left so quickly that nobody knew what had really happened," and it left 90 percent of the town destroyed in its wake, writes US Tornados. As the tornado crossed the Mississippi, it passed through Gorham, Illinois and left half of its population of 500 injured. In DeSoto, Illinois, "trees were snapped off at knee height and stumps then ripped out of the ground. No structure was left standing in the tornado's path."

The tornado passed through several mining towns, and in West Frankfort, when the miners came up to the surface, they encountered devastation. Continuing north, the tornado roared through Princeton, Indiana until it finally dissipated near Petersburg, Indiana.

The length that the tornado traveled was around 220 miles, the longest tornado track ever recorded, and it lasted a total of three and a half hours, according to Dusty Old Thing. However, the Electronic Journal of Severe Storms Meteorology states that based on the tornado's development around noon and assuming that "the super cell decayed approximately an hour after the final tornado (i.e., around 1900 CST)," it's possible that the tornado lasted as long as seven hours. Throughout its entire path, the speed of the tornado never went below 56 mph. Many have suggested that had tornado classifications existed at the time, the tornado would have certainly registered as an F5.

The damage of the Tri-State Tornado

In one day, 695 people lost their lives to a single tornado, and over 2,000 people were injured. Some were killed by flying debris. Others, writes Popular Mechanics, were trapped and killed under collapsing buildings. And even as anesthetics ran out, many still had to undergo surgery to have their limbs amputated. In many of the towns, residents had only seconds to react before the black clouds descended upon the town at a speed of almost 70 mph, while the tornado's own wind speeds reached up to 300 mph. Some people were thrown as far as a quarter of a mile by a tornado that was itself a mile wide. As the tornado passed through rail yards, boxcars and train tracks were torn from the ground. One person was reportedly cut in half "by a large brass bell that had fallen from the peak of the roof."

Storm Stalker writes that the mining industry in many of the towns was also devastated as "much of the mining machinery was ripped up and mangled beyond repair." And although some of the mines continued to operate in a limited capacity for another 20 years, things were never the way they'd been before the Tri-State Tornado.

To this day, the damage was a single tornado has been unparalleled. Thousands of people were suddenly rendered unhoused, a situation that was only worsened by the Great Depression four years later.

Buildings relocated

Murphysboro, Illinois was hit so badly that some refer to the 1925 Tri-State Tornado as the Murphysboro Tornado. Over 240 people died in Murphysboro, and this was when the tornado still had another two hours to travel. The winds of the Tri-State Tornado were so strong that houses were literally torn from their foundations and flown in different directions. Popular Mechanics writes that in Murphysboro, the house of Wallace Akin reportedly "began to levitate and, at the same time, the piano shot across the room, gouging the floor and carpet where I had played only moments before. The walls began to crack as the roof ripped free and disappeared, joining the swirling mass of debris. But the walls and the floor held as we and the house took flight." The house landed on top of their garage, which they realized had also flown and had landed on top of another house altogether.

Other buildings, like the schoolhouse in the unincorporated community of Ridge, were thrown several yards into a hillside. Thankfully no one was killed, but there were dozens of serious injuries.

Some homes were completely leveled, while others "virtually exploded in a cloud of shattered timbers and roofing." The damage spanned across three different states, and according to Building Safety Journal, the tornado "destroyed approximately 15,000 homes and caused $17 million in property damage ($1.4 billion adjusted for today)." Some towns didn't recover until World War II, when the abandoned lots left behind were finally rebuilt.

Why was the Tri-State Tornado so deadly?

Many have questioned why this tornado was so deadly. Some have speculated that the Tri-State Tornado was in fact a family of tornados, but given the continuous path of the Tri-State Tornado, this hypothesis is unlikely. But as the National Weather Service notices, "if the Tri-State Tornado was one massive storm, then why hasn't such a storm been documented in the 75 years preceding its occurrence? Could it be that the 1925 tornado was a rare event—occurring only once in several hundred years? Did it actually result from a cyclical supercell? Or could it be that we lack enough information to come to a definitive conclusion at this time?"

One thing that's for certain is that the lack of prediction or emergency warning services had a devastating effect. While it's understandable that the Weather Bureau may have been reluctant to release tornado warnings since they were considered unpredictable, if local meteorologists and forecasters had been allowed to study tornadoes, there could have been some semblance of an advance warning.

However, according to Electronic Journal of Severe Storms Meteorology, there's no meteorological explanation for the Tri-State Tornado's long track and destructive intensity. "Indeed, the somewhat mundane character of the synoptic situation leads one to wonder why very long-track tornadoes do not occur more frequently." It's also notable that compared to other tornados, which often have an unpredictable path, the Tri-State Tornado followed a topographic ridge and maintained a straight path for almost 200 miles.

Tri-State Tornado Aftermath

The Tri-State Tornado was followed by heavy rainfall, which led to flooding in many areas. The Wabash River near Griffin, Indiana flooded and cut the town off from the rest of Indiana. According to Orange Bean Indiana, "for days, the town was only accessible by boat or train." Despite it being incredibly difficult to get aid to the city, the American Red Cross arrived to set up tents for the residents. Martial law was even declared in Griffin and soldiers from the Indiana National Guard were brought as well.

Popular Mechanics writes that Murphysboro, Illinois suffered fires as the tornado trailed off. And "with the water system down there was no way to contain them." As a result, some who survived the collapsing building ended up succumbing to flames. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported in the aftermath of the tornado, "Scenes of suffering and horror marked the storm and fire. Throughout the night relief workers and ambulances endeavored to make their way through the streets strewn with wreckage, fallen telegraph poles and wires, and burning embers. The only light afforded was that of the burning area."

People looked for survivors for days, but in areas of flooding or fires, the chances of survival were low. But some people persisted on moving the rubble, looking for anyone who might remain, "literally tearing their hands to the bone in their efforts." Some found their efforts rewarded, while others realized after several days that they were searching in vain.

The lasting impact of the Tri-State Tornado

The one good thing that came out of the Tri-State Tornado was the realization that there should be a push in tornado awareness. The Weather Bureau wouldn't agree for almost another 25 years and continued to ban the use of the word "tornado," but this didn't stop local communities from figuring out a forecasting system themselves.

Popular Mechanics writes that "it was the beginning of local tornado-spotter networks," which are mentioned in newspapers after 1925. And the storm-spotter programs were effective and "contributed to a steady decline in the number of tornado deaths in subsequent years." In fact, according to Weather and Forecasting, the first hint of a downward trend in fatalities can be found almost directly after the 1925 Tri-State Tornado. In the 21st century, roughly 50 people are killed by tornadoes each year, but 100 years ago, that number was almost tenfold.

In the first half of the 20th century, all efforts were community based. Despite the fact that between 1920 and 1939, over 4,000 people died as a result of tornadoes in the United States, "the Weather Bureau did nothing to try to reduce the loss of life from these natural disasters." Systematic tornado prediction programs wouldn't be introduced for another 25 years. It wouldn't be until World War II, when the United States Army decided that they needed to protect their military installations, that tornado forecasting became a public service.

The Army decides it's worth it

On March 20, 1948, a tornado ripped through the Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma. Afterwards, Captain Robert Miller and Major Ernest Fawbush were asked by General Fred Borum to work on tornado predictions so that such an incident wouldn't happen again.

Five days later, the two meteorologists informed General Borum that the weather conditions on March 25th seemed suspiciously like those on March 20th. Despite acknowledging the "infinitesimal possibility of a second tornado striking the same area within 20 years or more, let alone in five days," according to Popular Mechanics, they decided to issue a tornado warning. And they were right. Another tornado ripped through Tinker Air Force Base, but this time "Borum had ordered planes hangared and air traffic diverted, sparing much damage to the base."

But according to the National Weather Service, despite seeing the benefit of tornado prediction, it was only applied to Air Force sites on the continental United States by 1951. It wouldn't be until March 17, 1952, that the Weather Bureau put out their first public tornado bulletin, forecasting tornadoes in Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas. And "although two tornadoes did occur in Texas, they were not in the outlook area."