What It Was Really Like To Attend The Imperial Ballet

Ballet and Imperial Russia are as entwined as dancers in a pas de deux. If you consider what are the most famous ballets of all time, such as those listed in The Ballet Herald, you will see the tremendous influence of Russia on ballet. Don Quixote, Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, and everybody's holiday favorite, the Nutcracker, were, if not outright created in Imperial Russia, transformed into famous revivals in Russia that are most the well-known versions today.

The ballet in Russia was driven from the top down — imposed by the state. It started with the czars, notably Empress Anna Ivanovna, who ruled from 1730 to 1740. She established, according to a historical sketch by Samuel H. Cross, the Imperial Ballet by naming the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Landé the dance master at the Military Academy in St. Petersburg (then the capital of Russia). Landé taught traditional dancing but also dramatics, which set the stage, so to speak, for his first well-received ballet in 1735.

Three years later, in 1738, Landé established Russia's first ballet school in the Old Winter Palace. Then in 1766, as told by Carol Lee's Ballet in Western Culture, Catherine the Great founded the Directorate of the Imperial Theaters. This institution gave state support and enormous prestige to all performing arts but especially the Imperial Ballet in multiple state-sponsored theaters. Catherine further declared that the Bolshoi Kammeny Theater in St. Petersburg was to be the epicenter of Imperial Ballet.

So what was it like to attend these performances?

You would see peasant dances at the Imperial ballet

Ballet on the surface seems the pinnacle of refinement and aristocracy. Yet if you were to sit down and watch one of the early Imperial ballets you would in fact be watching peasant dances. As described by History of Dance, the Italian Filipo Beccari trained orphans to become ballet dancers starting in 1764. But uniquely, the style of dancing taken from France and Italy was blended with Russian peasant dances, thus creating its own unique style. As told by an early 20th century historian, "It is a succession of brilliant pictures of the medieval Boyars, the semi-barbaric nobility. Every part of the ballet is meant to show the rich Byzantine colors, and primitive passions as set forth in a half-civilized garb."

The ironic part is, if you went back in time to witness one of these hurly-burly performances, while you would indeed be seeing mostly Russian dancers, the directors, choreographers, and managers were mainly Italian or French.

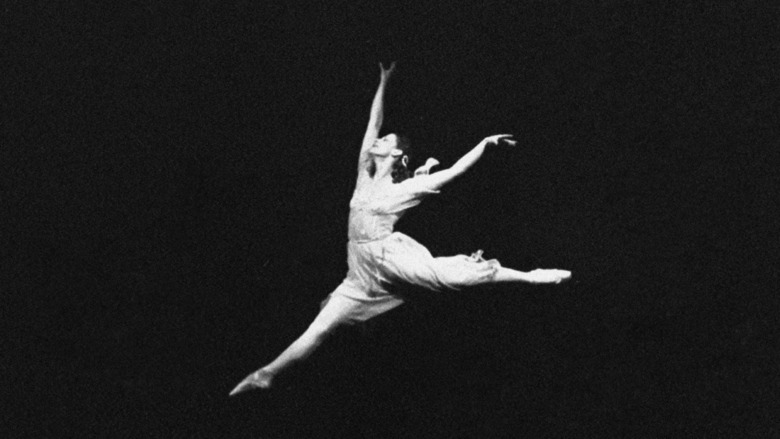

The father of Russian Ballet awed audiences with innovation

Moving forward in time to the early 19th century, you would see the Imperial Ballet reach its first height under the Swedish-born Frenchman Charles-Louis Didelot. According to Oxford Reference, Didelot was the choreographer for the Imperial Ballet starting in 1801. One seeing a performance of Didelot's would immediately begin to understand his impact on what would become St. Petersburg's style of ballet. Didelot was creative, having, before St. Petersburg, introduced innovations such as "flying ballet" on wires in Flore et Zéphire. This was one of the earliest uses of pointe dancing, which is dancing on the tip of the toe. Pointe Magazine notes that Didelot's machines would raise a dancer up so that they seemed weightless and floating. To audiences, the ballet had become grace and magic personified, but behind all the artistic genius was rigorous discipline.

In Russia, Didelot emphasized this lighter-than-air style and also heavily influenced stage design, choreography, and training. In 1811, he left Russia for Western Europe. However, according to a research paper by Samuel H. Cross, he did return in 1815 and remained until his official dismissal in 1830 by Czar Nicholas I after he fought with the director of the Imperial theaters, Prince Sergei Gagarin. Didelot ultimately retired in 1834.

Petipa and Elssler rocked the house

After Charles-Louis Didelot, the next height of the Imperial Ballet came with the French dance master Marius Ivanovich Petipa.

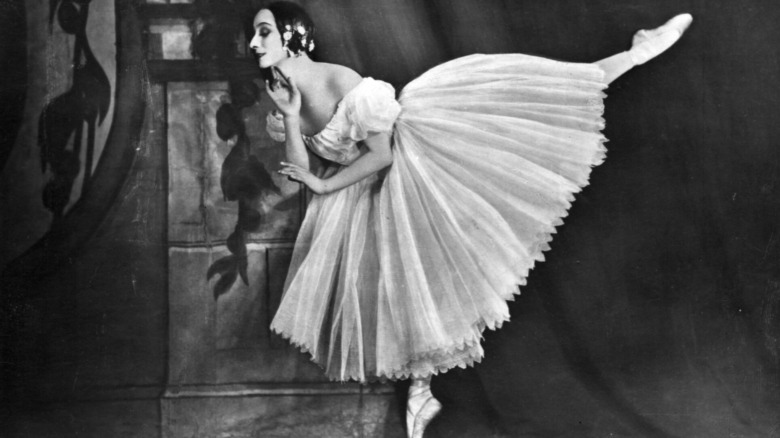

As described by the Marius Petipa Society, Petipa was invited to join the Imperial Ballet in St. Petersburg as its Premier Danseur in 1847. He was a hit, and Czar Nicholas I awarded Petipa after his first performance with a ruby and diamond ring. He thrilled audiences, as described by American Ballet Theatre, collaborating with the Austrian ballerina Fanny Elssler in ballets such as Paquita.

Elssler herself was a star, with Dance Research Journal describing her "swooning, voluptuous arms" that emphasized her gems, laces, and satins with a certain materialism. Ballet in Russia provides a glimpse of Elssler's impact on her audiences as she introduced Spanish-style dances to the Russia. She was so impressive that the Imperial Ballet signed her to contract for three seasons. She was more grounded than earlier ballerinas, with one witness declaring, "Madame Elssler offered a sunny, precise, natural and simply elegant type of dancing; ennobling it, she freed the theatre from the former showy jumps."

As for Petipa, he became so entranced by Russia that he became a citizen. This is no wonder, since the Imperial court, according to the Cambridge Companion, treated foreign artists many times better than the Russians who worked under them. Petipa, however, found most lasting fame by enthralling audiences with his productions.

What would you see in a Petipa ballet?

The Petipa Society describes how Marius Ivanovich Petipa choreographed The Daughter of Pharaoh in 1862, which told a story of how an opium-hallucinating English lord fell in love with an ancient Egyptian princess. Audiences would have seen him dance for the last time, as he moved up in the ranks as a ballet master. Petipa also crafted the best-known version of Don Quixote in 1869. Audiences today can appreciate his most famous ballets — The Sleeping Beauty in 1890 and the Nutcracker in 1892.

Audiences were charmed as ballerinas skipped with fantastical technical skill aided by reinforced block shoes. However, according to From Petipa to Balanchine, if you were to watch a Petipa ballet, then you were to see a loss of artistry. Where before, dancing en pointe was artistic in Petipa's day, you saw machine-like precision of multiple fouetté turns for spectacle.

As these aerial phenoms jumped higher year after year, so, too, did their skirts, which was not welcomed by all. As told by the Cambridge Companion, the Danish ballet master, August Bournonville watched Petipa's Don Quixote. He decried the "lascivious tendency" demonstrated by the ballerina's "excessively short skirts." As for the performance he wrote, "I sought in vain to discover plot, dramatic interest, logical consistency, or anything which might remotely resemble sanity. And even if I were fortunate enough to come upon a trace of it in Petipa's Don Quixote, the impression was immediately effaced by an unending and monotonous host of feats of bravura, all of which were rewarded with salvos of applause and curtain calls."

Where do you go to see the Imperial Ballet?

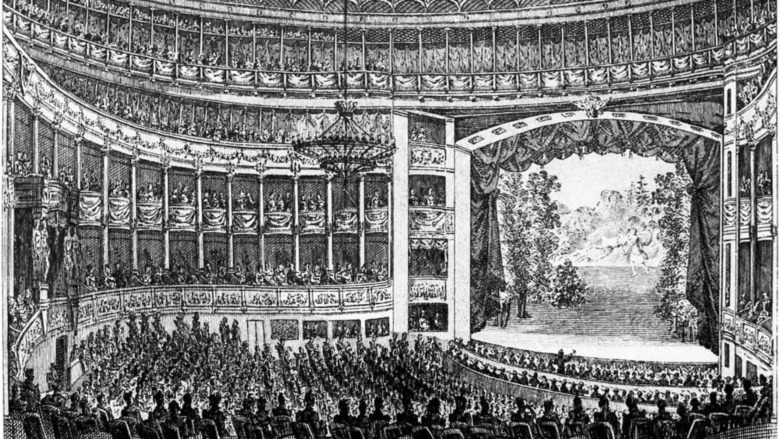

To see the first pinnacle of the Imperial Ballet, you needed to go to the Bolshoi Kamenny Theater in St. Petersburg. The name literally means "Great Stone Theater" and should not be confused with the also famous Bolshoi Theater in Moscow. The book, Serfdom, Society, and the Arts in Imperial Russia, traces the history of the theater to 1783. Commissioned by Catherine the Great, this was the first theater built for ballet and opera on a grand scale. Designed originally with three tiers, the structure could hold an audience of 2,000.

The theater went through several renovations, with one being induced by a massive fire. Yet phoenix-like, the Bolshoi Kamenny arose greater than before. By 1836, an attendee would be heralded into a chasm of czarist opulence. Five tiers of finery that gave a show supported, as the Cambridge Companion points out, by workshops that created elaborate sets for some of the most famous ballets in history.

One Russian academic study notes how theater goers were awed by the sets lit by the newest invention of electric lights (presumably arc lighting) in 1849. All this expansion came with the pressing need to impress its audiences more and more. As John Ardoin describes, the very heights of the space was built to hold that machinery to hoist dancers to new heights. It was to the West, Russia's "Imperial Theater." The building itself became one of the major attractions of St. Petersburg, according to the Mariinsky Theater.

A night at the Bolshoi Kamenny

The luster of the Imperial Ballet was captured by a British correspondent who attended an 1876 ballet in the company of ambassadors. As reported in the The New York Times, the reporter offered remarks on the audacity of the architecture that are overwordy even for 19th century prose. "...we ascended the majestic staircases of the Grand Theatre, and were speedily inducted into one of the most superb salles de spectacle that I ever beheld — superb. I mean, as to its size and proportions, its lighting and decorations."

However, at the same time, he noted that for the rest of the audience it was "singularly mean and comfortless... the arm-chairs look none too luxurious; while the floors of the boxes are uncarpeted, the chairs hard and exiguous." What seemed to really annoy him was that the boxes of the partitions were not high enough which leads to "...open galleries... and the general effect is consequently that of a gorgeous chapel instead of a theatre."

What about the performance? The reporter wrote, "Of the title, purport, and signification of the tremendous course of capering of which during three hours I was the suffering spectator, I have not the cloudiest idea; only I learned... it was a bird ballet...." As for the performers, he thought that they were perfectly drilled, "mechanically graceful, but not subtle." The audience, however, did not seem to mind and gave resounding applause to all the dancers.

Bleacher seating for the peasants

Ballet, particularly classical Russian Imperial Ballet, has an aura of aristocracy. This, on the one hand makes sense since the ballet was so closely tied to the royal court. On the other hand, there is ample evidence that attendees to the Imperial Ballet included commoners. Historians from the Dragomanov National Pedagogical University in Kiev describe how in the early 19th century, the Imperial Ballet began to open up a separate section of their theaters with simple wooden benches called a rayok with cheaper ticket prices. This allowed commoners to afford the ballet. Thus, it may sound surprising, but if you attended the Imperial Ballet in its hey-day, you would have seen a wide swath of Russian society, albeit separated.

There is no clear explanation as to why the ballet was made more accessible. The New York Times correspondent reported that there was an openness to at least the Bolshoi Kamenny, which made it more like a "gorgeous chapel instead of a theatre." He continued to wonder about this feature, "in a country where the gradations of nobilitary and official rank are so strongly yet so nicely marked as they are in Russia...."

It may be that the Imperial Court wanted to express itself and its power through the overawing grandeur of its theater. To the audience, it certainly did.

The Imperial Ballet moves to the Mariinsky

In 1886, the Bolshoi Kamenny reached the end of its life and was torn down with the land turned over, as reported by Russia Beyond, to the St. Petersburg Conservatory. Meanwhile, the Mariinsky Theater, as told by the theater's website, began to take on more and more productions in the years prior to the closing of the Bolshoi. The Mariinsky Theater began in 1859 when it was built over the earlier Circus Theater that had been gutted by fire. It was reopened as the Mariinsky Theater, so named after Maria Alexandrovna, the wife of Czar Alexander II.

After the Mariinsky became the chief Imperial Ballet in Russia, it was grandly renovated giving us the building known today. An enthusiast approaching the theater's elegant façade in the 21st century may well be entering the 19th. As described by Traveler, the almost 2,000-person-seat theater is a worthy successor to the Bolshoi Kamenny. As you enter you step into a foyer filled with bas-reliefs of Russian composers before entering the five-tiered auditorium over which hangs a chandelier the size of a czar's ego. Indeed, the three-tiered royal box is opposite of center stage, almost sucking up as much attention as the ballerinas.

The Mariinsky is famous for premiering some of the best known ballets. The Sleeping Beauty and the Nutcracker both premiered at the Mariinsky. The Mariinsky is still in operation today and offers classical Russian ballets and operas.

The Nutcracker was considered boring and foolish

Would you like to go back in time and see the premier of The Nutcracker or Swan Lake? These ballets with scores by Peter Tchaikovsky are classics. However, the audiences who saw the Nutcracker's premier in 1892 were anything but charmed. Nutcracker Nation describes one big gripe was that it was made for children. "In the first scene the entire stage is filled with children, who run about, blow their whistles, hop and jump, are naughty, and interfere with the oldsters dancing. In large amounts this is unbearable." Another critic referred to the ballerina Antonietta Dell'Era as "corpulent" and "podgy." One writer quoted in the Cambridge Companion opined, "Nutcracker can in no event be called a ballet."

The audience did enjoy the music. The Life and Ballets of Lev Ivanov quotes, "In sum: it's a pity that so much good music is expended on such nonsense, so unworthy of attention; but the music in general is excellent." Another critic in 1893 summed up the feeling. "It is difficult to imagine something more boring and foolish than the Nutcracker."

Swan Lake at its premier in 1877 was a flop, too. As the Moscow Times reports, Swan Lake's plot and characters revolved around Russian and German folklore in which a prince tries to break the curse of an evil sorcerer who has transformed a princess into a swan. The critics found it too German for their taste.

Who would you see if you attended the Imperial Ballet?

When you watched an Imperial Ballet you gazed at highly disciplined dancers who were almost always of humble origins. The Imperial Ballet schools, through the financial backing of the Imperial Court, offered a way out of poverty or desperate situations. The ballet schools conducted exams and accepted promising students. For example, one of the premier ballerinas of the Mariinsky was Anna Pavlova who, according to Britannica, was left fatherless at age 2. In 1891, however, she was accepted by the Mariinsky and became the prima ballerina in 1906.

The Dragomanov National Pedagogical University notes that she was most famous for her performances of the "Dying Swan" from Swan Lake. Audiences who saw Pavlova would see an artist at her most expressive, as told by Ballet 101. Using fluid upper body movements and tiny steps, Pavlova would evoke the death of Odette. A later ballerina who viewed film of the "Dying Swan" commented in Dance Anecdotes, "Even today her Swan is striking — the flawless feeling for style, the animated face — although certain melodramatic details seem superfluous."

Ballet for the Proletariat

Even as the Imperial Ballet was seemingly in an endless golden age, it came to an abrupt end. As described in Christina Ezrahi's Swans of the Kremlin, the artists of the Imperial Ballet were resistant to Bolshevik takeover of the country in 1917. That year, according to the Mariinsky Theater, the Mariinsky was taken over by the government and control was granted to the People's Enlightenment Commissariat.

Those who saw a performance under the Soviets would see stark changes. Instead of aristocrats, the audience was filled with proletariat who, with free tickets in hand, wore shawls and greatcoats rather than tuxedos and evening gowns. These workers soon came to appreciate the ballet and the ballerinas. Ezrahi quotes one critic describing the audience, who "applauded and howled with such violence that all the old theater rats scurried off in horror to the snuggest little holes." In 1935 the Mariinsky was renamed the Kirov.

Many of the performers were aghast at the changes, and the Mariinsky Ballet lost about 40% of its dancers. At the same time, the ballet initially became not so much an instrument of Soviet propaganda but rather as stated by Ezrahi, "an escape from the horrors of revolutionary reality."

Russian ballet today is still big

The ballet survived, but as the decades passed it was co-opted for communist purposes. For example, as described by the Moscow Times, if you watched Swan Lake in the Soviet era, you find a happy ending instead of a double suicide, as well as other modifications reflecting the battle between communism and capitalism. Swan Lake was even used by the state apparatus to preempt regular television programming during the death of communist secretaries until a successor could be named.

While the Soviet Union produced ballet phenoms like Mikhail Baryshnikov, Rudolf Nureyev, and Alexander Godunov, it is telling that these dancers, as detailed in Russia Beyond, all defected. After the fall of the Soviet Union, a new era seemed to beckon. The New World Encyclopedia details how in 1992, the Kirov Theater assumed its old name of the Mariinsky and continued its central role in ballet innovation.

Ballet is still a passionate and important art in Russia. While, as described by Slate, the worldwide favor of ballet has declined, in Russia it is still highly popular. Crowds at theaters in Moscow and St. Petersburg are highly vocal in the approval of the individual feats of their dancers. As testament to this passion, in 2013 the Bolshoi dancer Pavel Dmitrichenko hired goons to throw acid into the face of director Sergei Filin for not giving his girlfriend a leading role. Perhaps Dmitrichenko's story can be turned into a new tragic ballet by some enterprising choreographer?