The Tragic Life Of Mithridates, The Poison King

Mithridates is one of those extremely fascinating kings from our past who few know about today, outside of ancient history lovers. He may not get the publicity of famous people like Cleopatra or Spartacus, but Mithridates certainly captured the imaginations of Roman writers. From his birth all the way until his death, accounts of Mithridates' life were filled with legends, prophesies, and folklore. But unlike a mythical figure like King Arthur, there was much more truth to the tales ... or at least exaggerated truth.

Mithridates was widely respected throughout the ancient world as a powerful ruler who fiercely opposed the expanding Roman Empire. For this reason, he was known to some as Mithridates the Great, but his far more intriguing nickname was the Poison King. After a traumatic experience in his childhood, Mithridates became obsessed with toxins, venoms, and poisons of all sorts. This obsession never ceased and drove him to become one of the top experts in toxicology at the time.

Though his life was filled with impressive accomplishments, it was not without sorrow. Mithridates often lost loved ones, was sometimes betrayed by those closest to him, and eventually everything he had built was taken away from him. But these more depressing aspects only add to the enthralling layers to this complex ancient king.

The legendary origins of Mithridates VI

In 135 B.C., people across the ancient world were amazed at the sight of a comet nearly as bright as the sun as it traveled across the sky. Later that year, a prince was born in the royal city of the kingdom of Pontus on the Black Sea, in what is now modern-day Turkey. This prince, who would later become the Poison King, was given the lengthy regal name of Mithridates VI Eupator Dionysus.

Though long before he was forever associated with poison, Mithridates was tied to several prophecies in the ancient Near East that foretold of a savior king who would destroy an evil empire. A bright star was the sign of his arrival, so many believed Mithridates was this prophesied ruler. And it is not hard to understand why because the comet must have been a spectacular event to witness. According to Adrienne Mayor in her book, The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, not only did Roman historians write about the comet, but so too did the ancient Han Chinese record the spectacle all the way on the other side of the world.

Mithridates also claimed to be descended from the Persian kings on his father's side and from Alexander the Great on his mother's side. This would have meant he was related to the two most powerful families of the time. But Mithridates was so charismatic and such a master of propaganda throughout his reign that many people believed the prophecies and stories of his extraordinary lineage, whether they were true or not.

Mithridates' father was murdered with poison

In 120 B.C., the king of Pontus held one of his renowned feasts for the royal court. The esteemed guests and courtiers were served delicious dishes of lamb, venison, and tuna, paired with bowls of olives, cherries, peaches, apricots, figs, nuts, and bread. While performers danced to the beautiful music of harps and drums, and as Indian snake charmers awed the partygoers, the entertainment came to a halt when the king suddenly clutched his throat, struggling to breath. He then fell out of his chair and laid dead on the floor.

Although it was never proven, Mithridates' mother most likely had his father assassinated with poison, says Philip Matyszak in his book, Mithridates the Great: Rome's Indomitable Enemy. And as the eldest son of the king, Mithridates ascended the throne. The Roman historian, Justin, said that once again a bright comet traveled across the sky the year of his coronation on 119 B.C. (also seen by the Han Chinese as well, says Adrienne Mayor).

But regardless of another glorious omen, this was a dark time for the young ruler who had just lost his father and was not sure if his mother, or other conspirators, would come after him next. Since Mithridates was still so young, his mother ruled for him as regent in his place, says Britannica. The young ruler accepted these circumstances at first, but it did not take long before he fled the palace to live in the wilderness with a very small entourage of loyal companions.

Mithridates left the capital to build up his immunity to poisons

Mithridates strongly suspected that his mother, or other enemies in the royal court, would try to eliminate him with poison like his father. So, while he traveled through the remotest parts of the kingdom with his close friends, Mithridates began to take in minor doses of the poisons and toxins he found in order to build up his immunity to them as much as possible.

Among the poisonous plants and animals that Mithridates gained experience in handling were nightshade, hellebore, hemlock, and monkshood, as well as venoms and toxins from snakes, scorpions, spiders, slugs, and birds. He also experimented with poisonous minerals, such as arsenic, mercury, and sulfur. Gradually, Mithridates was becoming the Poison King of legend.

On his journey across the countryside, Mithridates did not just build up his poison resilience, but the young ruler was also building up support among his people. To them, Mithridates was exiled by a vile, corrupt court and deserved his rightful place on the throne. With the people on his side, it was around 116 B.C. that Mithridates returned to the palace, deposed his mother, and threw her into prison, says World History Encyclopedia. He then purged from the court anyone else who may have been involved in his father's assassination.

Mithridates continued to study poisons and antidotes

Once he had secured the throne, Mithridates had laboratories established in the capital and across the kingdom. Any type of material associated with poison that Mithridates' agents could find was then brought to these royal workshops and studied. Plus, the Poison King had special gardens created where he could grow any poisonous plant he needed.

Adding to what he had already experimented with from the wilderness of his kingdom, Mithridates continued to expand his personal collection of poisons throughout his life. Eventually, the collection became the largest of its kind and might have contained crystalized snake venom from India, mushrooms from Scythia, Egyptian scorpions, jellyfish and stingray spines from Libya, among many other exotic samples gathered from every corner of the known world.

Adrienne Mayor says that Mithridates built upon the previous research and knowledge of experts like Attalus III, Nicander of Colophon, and several others. He also conducted his own experiments on prisoners, associates, and himself to create a huge compendium of poisons and antidotes with all their known properties.

The Poison King supposedly created a universal antidote for all poisons

Pliny the Elder and many other ancient authors claimed that all that studying truly paid off because Mithridates was able to create a universal antidote for all poisons called Mithridatium, via the University of Chicago. Supposedly, the concoction may have had over 50 different ingredients that were ground into powder, mixed with honey, and made into chewable tablets. Many years after Mithridates' death, the Roman medical writer, Celsus, said that altogether the mixture weighed around three pounds with tablets broken off and eaten daily. Mithridates not only ate these but also drank small doses of poison every day as well to continue to build up his immunities.

Mithridates did not create Mithridatium alone and instead was greatly helped by his chief physician, Krateaus, along with Scythian shamans and other healers. With their help, many more experiments were conducted so much more information could be gathered.

How Mithridates VI lived and loved as king of Pontus

Mithridates was not just a poison expert and skilled general who was brave enough to fight on the front lines in battle. He was also an excellent horseman who became a champion of several chariot races in Greece and Asia Minor (Turkey). Adrienne Mayor says that he most likely began training to drive chariots as young as 8 or 9 years old. As an adult, Mithridates was so strong and skilled that he could drive a chariot pulled by ten horses, an extraordinary accomplishment. Plus, ancient accounts also claimed he was an excellent boxer, wrestler, and swimmer, especially in his youth.

Poison was not just work and survival for the Poison King. Mithridates also showcased his incredible knowledge and ability to withstand poisons in jaw-dropping spectacles. Just like how he fully embraced the amazing comet at his birth and the prophecies connected with it, Mithridates demonstrated to his guests that he could drink poisoned wine or eat meat laced with toxins in order to strengthen the myth of his invincibility.

Mithridates was very busy in the bedroom as well, with 20 known children throughout his life born from several different wives and concubines. His last queen, Hypsicratea, also fought from horseback like a legendary Amazonian warrior. Not only could she wield an axe, sword, lance, or bow and arrow, but she never left Mithridates' side no matter how dangerous the situation was, whether in war or while the king was in exile.

How Mithridates created his empire on the Black Sea

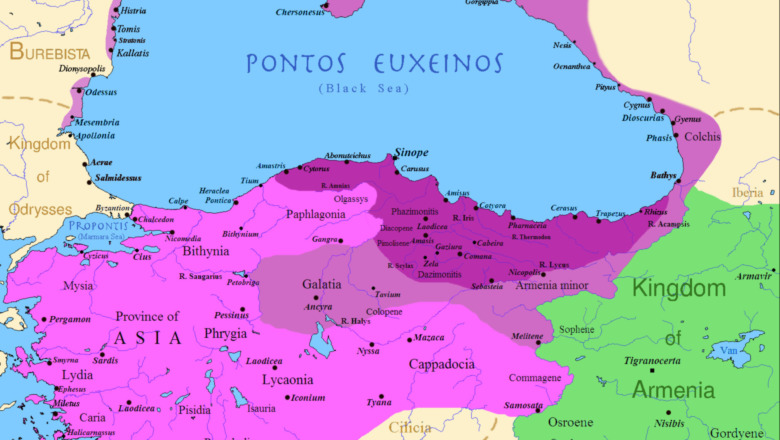

From 113 to 95 B.C., Mithridates expanded the Kingdom of Pontus by conquering Colchis, defeating the Sarmatians to the west and the Scythians to the north, and he incorporated many Greek cities along the Black Sea coast in exchange for protection from the hostile nomads on their borders, says Kings and Generals.

To the south, Mithridates secured his border by cementing an alliance with the Armenian king, Tigranes the Great, with a marriage to his daughter. However, when Mithridates seized Cappadocia in 97 B.C., the Romans began to see him as a major threat. The Romans had already conquered large parts of Asia Minor, and even though Cappadocia was still free, the region was loyal to Rome. So, when Mithridates installed a puppet ruler on the throne of the neighboring kingdom of Bithynia as well, the Romans were fed up. The Romans first restored rulers in Cappadocia and Bithynia that were loyal to them and were then ready to deal with the ambitious king of Pontus.

Mithridates massacred thousands of Romans and Italians in Asia Minor

Mithridates declared war on the Romans after the new king, Nicomedes IV of Bithynia, attacked Pontus on the Roman's behalf in 89 B.C., according to World History Encyclopedia. After driving back Nicomedes' forces, Mithridates then invaded Bithynia in retaliation, crushing both the armies of Bithynia and the Romans in the process. When the Roman consul in command of the army, Aquillius, was captured, he faced the horrific punishment of having molten gold poured down his throat.

Mithridates ordered the brutal execution because the animosity and hatred of the Romans had reached a breaking point throughout Asia Minor. The Romans had taken over most the region and were not kind to the people they dominated. Many suffered from the vicious amount of taxes the Romans forced them to pay, pushing them into lives of utter poverty and squalor. The people of Asia Minor were ready to revolt against their foreign overlords, and Mithridates knew it.

In 88 B.C., Mithridates orchestrated a horrific event known later as the Asiatic Vespers, which was an atrocity far worse than the execution of Aquillius. All in one day, somewhere between 80,000 to 150,000 Romans and Italians were killed in the cities, towns, and villages of Asia Minor. For even more incentive to carry out the murders, Mithridates granted freedom to slaves who killed their Roman masters, and the debts were erased of those who murdered Roman creditors. The Romans knew Mithridates was responsible and would never forget it.

The First Mithridatic War

The First Mithridatic War was going great for the Poison King. Not only had he defeated Nicomedes and Aquillius, but his strong stand against the Romans inspired others to seek their freedom from oppression as well. So, when the Greeks asked Mithridates to help them achieve this, he happily agreed and sent an army to remove the Romans from Greece.

The Romans had been quite preoccupied fighting a war with their Italian allies, but once the conflict was settled, the formidable Lucius Cornelius Sulla led an army to handle Mithridates. In 87 B.C., Sulla landed in Greece with five legions and sacked the sacred shrine of Delphi, using its treasure to hire more soldiers, writes World History Encyclopedia. The Romans' larger army seized Athens and then defeated Mithridates' general in Thessaly. At this point, Mithridates began to face his own civil unrest at home, so he was forced to negotiate the Peace of Dardanus with Sulla in 85 B.C., ending the war.

Mithridates continued to resist the Romans

When Murena, the Roman governor of Asia, invaded Pontus in 83 B.C., hostilities resumed, and the Second Mithridatic War began, says Philip Matyszak. Murena was no Lucius Cornelius Sulla, so when Mithridates was able to gather his forces and confront the Romans, he completely crushed them and swiftly put an end to the brief war.

Rome and the kingdom of Pontus were once again at peace, but Mithridates knew it would not last long. Still, to many throughout Asia Minor, Mithridates was the hero that would save them from the evil Roman Empire. The devastating taxes had only gotten worse, so people were even forced to rely on sex work or having to sell their own children into slavery just to pay off their debts, says Adrienne Mayor. At times, the Romans were so cruel that they tortured individuals in order to find out about every single thing they owned to seize before selling them into slavery to pay all that was owed.

To prepare for the final confrontation with Rome, Mithridates made alliances with the Cilician pirates, the Ptolemaic pharaohs of Egypt, Thracian tribes, and the rebel slave-leader Spartacus. Confident in this coalition, Mithridates was ready to fight the Romans again by 74 B.C.

The best Roman generals eventually crushed the Poison King

When King Nicomedes IV of Bithynia died in 74 B.C., he gave his kingdom to the Romans, says World History Encyclopedia. There was no way that Mithridates was going to just allow this to happen, so Mithridates placed a king of his own choosing to rule over the nearby kingdom instead. Understandably, the Romans were not pleased with this and sent their general, Cotta, who was easily dealt with by Mithridates. The Romans then upped the ante by sending a different commander who was on Lucius Cornelius Sulla's level, Lucius Licinius Lucullus.

First, Lucullus forced Mithridates to flee his kingdom and seek refuge in the kingdom of Armenia. After the Roman general pursued him there, Lucullus then managed to take the Armenian capital as well. Luckily, Mithridates escaped before he was captured, and his fortune did not end there because Lucullus was recalled by the senate back to Rome shortly after.

Another extraordinary commander, Pompey the Great, quickly took Lucullus' place and made the strategic move to eradicate one of Mithridates' main allies, the Cilician pirates. The Roman general then invaded Pontus once more. As Pompey continued to advance towards Mithridates, the king could do nothing to stop the Romans, so he was forced to leave the royal city for the last time.

Mithridates was betrayed by his sons before his death

For help, Mithridates first went to his son, Machares, in his territories to the north along the Black Sea. However, he was utterly dismayed to find out that Machares had already come to an agreement with Rome. Mithridates was so furious over this betrayal that he had his son executed. When his other son, Pharnaces, learned about the murder of his brother, he too turned on his father (via World History Encyclopedia).

With both his son and Pompey now pursuing him, Mithridates escaped to a citadel with his two young daughters. He knew that if he was captured by the Romans, they would humiliate him by parading him through the streets of Rome in a triumph. This was a grave insult that he would not allow to happen. The Poison King was prepared for a situation such as this. Within the sheath of his sword, Mithridates carried poison with enough potency that it was able to kill even him.

However, his daughters did not want him to die alone, so they begged for their own doses as well. Mithridates reluctantly agreed, and the poison worked quickly on them. Yet, when he took the remainder, it failed to do the job because there was not enough of it left to overcome his strong immunity. So, the king ordered his servant to end his life with a blade instead. Pompey received the news of the king's death in 62 B.C. In an act of great respect, the Roman then ordered that Mithridates be given a royal funeral and laid to rest in the tombs of his ancestors.