The Lockerbie Bombing: The Tragic True Story Of Pan Am Flight 103

The bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 on December 21, 1988, a mere four days before Christmas, continues to vex intelligence and law enforcement agencies in Europe and the United States. Although Libya and one of its former intelligence agents have been held responsible, the identity of the perpetrators is still far from certain. Politics, corruption, and special interests have dogged the victims' attempts to find justice and closure for the horrific incident that killed 270 people during one of the most joyous times of the year.

Since the day of the bombing, different governments, individuals, and institutions have put forward a host of theories regarding the identity of the perpetrators. The list of the accused and their sponsors ranges from the United States to Iran. This is the true, convoluted, and tragic story of the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103, one of the worst air disasters in aviation history.

The flight and the bombing

On December 21, Pan Am 103 was beginning the second leg of its Frankfurt-London-New York-Detroit route. The Boeing 747, known as the Clipper Maid of the Seas, left London Heathrow with 243 passengers and 16 crew members, including 189 Americans. Forty minutes into the flight, the plane had reached the coast of Scotland. Per the official accident report, the pilot requested clearance to proceed with the transatlantic portion of the flight from Shanwick Oceanic Area Control at 18:58 UTC. At 19:02 UTC, the officers at the air traffic control center cleared the flight to proceed but did not receive a response. One of the ground officers only reported a "strange noise," presumably from the cockpit. Once five different objects showed up on the radar instead of the plane, the officials began to fear the worst.

The Shanwick officers' fears were correct. At around 19:00 UTC, a bomb in a Samsonite suitcase exploded, ripping through the fuselage and fragmenting the plane. The Irish Times quoted witnesses as seeing ball of fire in the night sky as wreckage rained down upon the small Scottish town of Lockerbie. The FBI ultimately recorded debris over an area of 845 square miles. Soon, teams from international intelligence agencies and security bureaus, such as the FBI and CIA, were on the ground, looking for any sort of wreckage from the plane. The investigators sought the black box and anything else that could help reconstruct the tragedy.

Deaths in the air and on the ground

The explosion killed all 259 people aboard the plane. While some died instantly, Dr. William Eckert of Wichita State University told the Associated Press that around 148 passengers and the pilot may have survived the initial explosion only to experience the horror of a 31,000-foot drop to the ground. Many of them would have passed out initially from lack of oxygen but regained consciousness somewhere between 15,000 and 10,000 feet. For them, the seemingly never-ending drop must have been horrific. Many were found holding crucifixes, suggesting that they expected to die. Dr. Eckert's testimony was confirmed to the AP by pathologist Dr. Anthony Busuttil, who posited that at least two passengers may have survived the crash. A rescuer identified one as Noelle Berti, a flight attendant whose pulse was still present when she was found, although her condition was such that she would not have lived even with medical treatment.

In addition to the victims on the plane, 11 people on the ground were killed. The aircraft's wings struck numerous houses on the Sherwood Crescent in Lockerbie. Two of the 11 victims had their house reduced to ash, their bodies completely incinerated and never found. Twenty-one of the damaged houses were demolished, while more required extensive repairs.

The first suspect was a man who'd missed the flight

According to the BBC, on the afternoon of December 21, Jaswant Basuta was bound for a new job in New York City. His relatives had insisted on celebrating his success with a toast at a Heathrow bar. Basuta rarely drank, and that afternoon, he had too much and lost track of time.

Upon realizing the hour, a tipsy Basuta took leave of his relatives and sprinted through the terminal to Gate 14, but the plane was already taxiing to the runway. Pan Am ground crew refused to call the plane back despite his pleas. After two hours sobering up in the waiting area, Basuta encountered two police officers, who asked him why he had missed the doomed flight. Basuta did not know about the bombing, and since he had conveniently missed it, he was naturally looked upon with suspicion. The authorities released him when it became apparent that he had missed the flight by accident.

Another "survivor," Kim Wickham, told the Daily Record that she was headed to New York to spend Christmas with her family. Much to their anger, she changed her flight at the last minute and spent Christmas with her friends in Germany instead. Sex Pistol John Lyndon and his wife Nora told The Guardian that they had also missed the flight because she did not finish packing on time.

Initial reactions and suspects

Intelligence agencies had some warning prior to the bombing that allowed them to identify preliminary suspects. According to The Washington Post, an anonymous caller phoned a potential threat to the US embassy in Helsinki on December 5. Supposedly, a Finnish woman would unwittingly carry a bomb onto a US-bound Pan Am flight from Frankfurt within two weeks of the call. The caller also provided two names associated with the Palestinian Abu Nidal militia. This memo pointed to Middle Eastern terror groups but was dismissed.

Within hours of the bombing, the CIA had four potential suspects. According to a CIA memo from December 22, 1988, anonymous claims identified the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, Israel's Mossad, the Lebanese militia Islamic Jihad, and the Northern Irish Loyalist Ulster Defense Force. The CIA believed Iran had carried out the bombing in revenge for the destruction of Iran Air 655 over the Persian Gulf.

French and British intelligence suspected Libyan involvement, given President Muammar Gaddafi's support for the 1986 West Berlin nightclub bombing and his ongoing feud with the United States. American investigators found supporting evidence while combing through the Lockerbie wreckage. According to Christopher Joyner and Wayne Rothbaum, investigators discovered a microchip from the bomb that matched the type used to blow up three flights over Chad, Togo, and Niger between 1984 and 1989. In addition, Senegal arrested two Libyan men with Semtex explosives that investigators matched to the Lockerbie bomb fragments. This provided more direction for the investigation, which shifted from Iran to Libya.

Libya is sanctioned

Following the French intelligence services' leads, British intelligence identified two Libyans, Abdelbaset al-Megrahi and Lamen Khalifa Fhimah, as persons of interest. Both men were identified as Libyan intelligence operatives, again suggesting a link to Gaddafi. But until they could be tried, their involvement could not be confirmed.

The UK, with American support, requested the men's extradition for trial in the UK or the United States. Gaddafi refused, citing the Montreal Convention's "aut dedere aut judicare" ("either give or judge"). This principle allowed Libya to try terror suspects on its own soil. The United States decided to force Gaddafi's hand with UN Security Council Resolution 748. These sanctions placed restrictions on Libya's aviation industry, military, and high-ranking government officials until Gaddafi withdrew his support for terrorism.

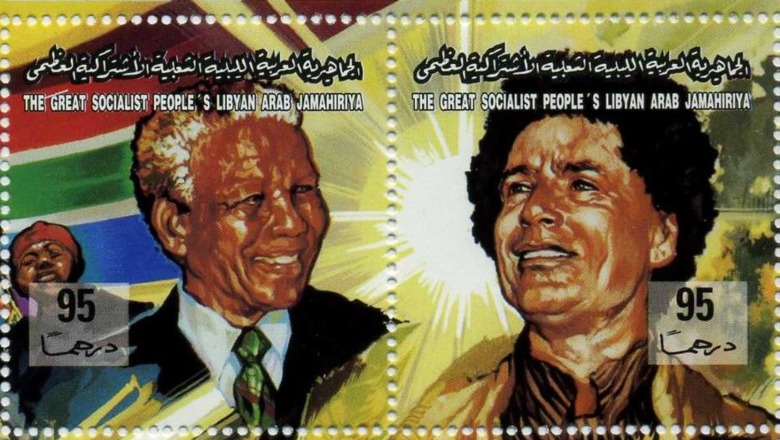

According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics, Resolution 748 cost Libya almost $20 billion in economic losses. However, the sanctions were not as effective as hoped. In Europe, British government agencies opposed the sanctions and had hoped other UNSC members would veto the resolution. The Times of Israel reported that the British Department for Trade and Industry was most concerned with the economic impact of British exports to Libya. The New York Times added that the Arab League refused to enforce the sanctions, giving Libya ways to bypass them. After 1994, Gaddafi found an unlikely champion in South African President Nelson Mandela, who violated the sanctions with a visit to Libya in 1997. Under such circumstances, the quest for justice had reached in impasse.

The Camp Zeist trial

As the impasse continued into 1997, international bodies offered to mediate, and the Arab League proposed a compromise. The extradited suspects could be tried in a neutral country outside the UK. With support from South Africa and the Arab League, American Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and British Foreign Secretary Robin Cooke offered Gaddafi a deal: The two accused would be tried by a Scottish court in the Netherlands at Camp Zeist, a former NATO base. If they were found guilty, they would serve their sentences in British prison.

Gaddafi accepted the offer and extradited both men to face trial. The proceedings began in May 2000. Lamen Khalifa Fhimah (pictured above with Gaddafi) was found not guilty. He had been in Sweden on the day of the bombing and could not have been involved. Abdelbaset al-Megrahi's trial was more complicated. The critical piece of evidence was the testimony of the man who had allegedly sold the clothes in the suitcase bomb.

During al-Megrahi's trial, the main prosecution witness was a Maltese national named Tony Gauci. Gauci testified that he had sold the clothes to a man of Middle Eastern appearance who resembled al-Megrahi. However, he could not match the man he had met in Malta with the suspect on trial with certainty. Per American Radio Works, Gauci could only recall that a picture of al-Megrahi in a magazine resembled his client. However, his testimony was enough to convict al-Megrahi, who was sentenced to life imprisonment in the UK. Later evidence has cast serious doubts about his guilt.

Libya accepts responsibility

Abdelbaset al-Megrahi's conviction vindicated Gaddafi's accusers. With the sanctions taking their toll and affecting Libya's lucrative trading relations with Europe, Gaddafi announced, per The New York Times, that Libya would take responsibility for the bombing and pay $3 billion to the families of the victims. In return, the UN lifted the sanctions under Resolution 748 and allowed Libya back into the international community.

While Gaddafi's admission provided a sense of closure to the victims' families, the Libyan president continued to deny responsibility in private. Had Gaddafi accepted responsibility just to have the sanctions lifted? Had special interests in Europe lobbied for leniency despite Libyan complicity? The web of special interests suggests that this scenario is at least partially true.

Remember, parts of the British government had opposed the sanctions from the beginning. Oil companies such as Shell and British Petroleum joined them, hoping to obtain contracts to survey Libya's oil and gas fields, once the sanctions were gone, per The Guardian. Shell obtained its contract in 2005, while BP successfully negotiated a deal in 2007. Silvio Berlusconi's Italy also had economic interests in removing the sanctions. The Wall Street Journal reported on Italy's investments in Libyan oil and gas in 1999, but CNN and The Malta Independent reported a more current problem in 2004: Italy was facing a surge of undocumented economic migrants passing through Libya, and Gaddafi's help was needed to stop it. Berlusconi lobbied American president George W. Bush to restore full relations with Libya in return for Gaddafi's cooperation in curbing migration.

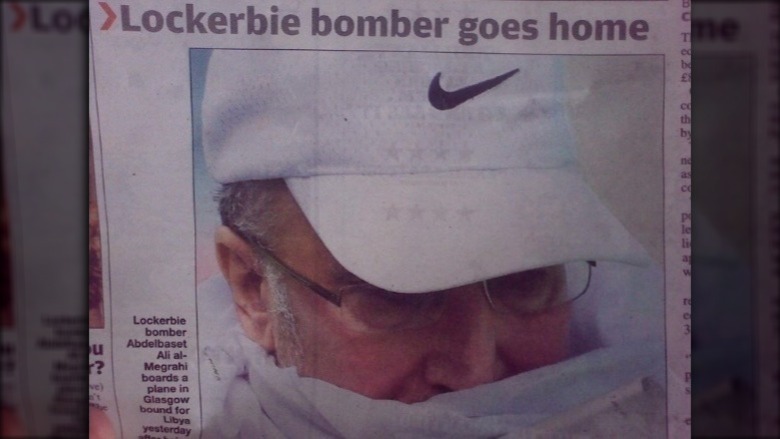

Abdelbaset al-Megrahi is released

Once the sanctions on Libya were lifted, the emotion over Gaddafi's role died down somewhat. However, the BBC reported in 2009 that Abdelbaset al-Megrahi was dying of cancer and had requested a commutation of his sentence on compassionate grounds. If granted, he would be allowed to return home to Libya to live out the remaining six months doctors believed he had left. His appeal caused an uproar in Britain, creating a rift between those who wished to show mercy and those who wished to see him die in prison. Ultimately, the court granted him clemency, to the outrage of the victims' families.

Once again, special interests had tipped the scales. As mentioned earlier, BP had secured a major oil and gas deal in Libya and did not want to jeopardize it. Business Insider reported that BP lobbied vigorously for the transfer deal, although the company initially denied it, per NBC New York. The cancer diagnosis allowed the British government to avoid discussing this angle, referring to the diagnosis as "a gift," al-Megrahi's biographer John Ashton told The Guardian. While the media portrayed the release as purely a matter of special interests, there was another reason for releasing al-Megrahi: New evidence had surfaced in 2008 that suggested a miscarriage of justice in the original trial.

Was there a miscarriage of justice?

Despite his conviction, Abdelbaset al-Megrahi had maintained his innocence throughout the trial and during his time in prison. Academics such as Professor Hans Köchler had said on record with the BBC as early as 2002 that the evidence against him was circumstantial. Al-Megrahi's conviction rested mostly on the testimony of Maltese national Tony Gauci, the alleged salesman of the clothes used to pad the bomb that destroyed PanAm 103. Fresh evidence eventually threw Gauci's testimony into serious doubt.

In 2008, The Herald published an 800-page report claiming to clear the alleged Lockerbie bomber on the basis of inconsistencies in the original testimony. The Herald reported that the prosecution in the case had suppressed evidence that would have exonerated the Libyan, namely the records of Palestinian groups plotting to blow up passenger airlines. These conversations were never released. More importantly, The Herald also revealed that the CIA had paid Gauci, the prosecution's star witness, $2 million for his testimony to implicate al-Megrahi. The payment cast doubt upon Gauci's identification, and al-Megrahi's family made it the basis of his appeal.

The corruption during the trial and the suppression of these details suggest that al-Megrahi's claims of innocence may have been legitimate, although his innocence still would not exonerate Gaddafi. Tony Gauci died in 2016, remembered in the Times of Malta as the man whose corruption sent "an innocent man" to jail.

A former Libyan official blamed Gaddafi

In 2010 and 2011, the Arab Spring arrived in Libya and soon escalated into full-blown civil war. Gaddafi was killed in a French bombing raid on Tripoli, leaving a power vacuum for a fragile coalition of Islamists, anti-Gaddafi politicians, and generals to fill. The face of the interim National Transitional Council, per Deutsche Welle, was former Gaddafi loyalist and justice minister Mustafa Abdul Jalil. Jalil eventually sought asylum in Sweden, where he made some damning claims regarding his former boss' complicity in the Lockerbie Bombing.

In an explosive interview with Swedish newspaper Expressen, Jalil claimed to have documented proof that Gaddafi had personally ordered the Lockerbie bombing. These claims received some attention in the UK. The BBC quoted Scottish MP Murdo Fraser, calling the allegations "disturbing but believable." For Fraser, Jalil's claim explained why Gaddafi had refused to extradite al-Megrahi, lest he implicate the Libyan president during his trial. However, Jalil never presented any evidence in support of his claims.

Attention turns east

Following Abdelbaset al-Megrahi's death, attention turned to the original suspect, the Islamic Republic of Iran. In the 2014 Aljazeera exposé Lockerbie: What really happened, Iranian defector Abolghasem Mesbahi claimed that Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini had personally approved the plan. A anonymous Israeli source quoted in the Times of Israel claimed that Khomeini was behind the contracting of Ahmad Jibril, member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, to carry out the bombing. According to Robert Baer, Lockerbie was only one of five bombings the Iranians had planned.

America's intelligence agencies posited that if Iran was responsible, it was in revenge for the USS Vicennes' downing of Iran Air 655 over the Persian Gulf in 1986. According to Real Clear World, Khomeini had promised that the skies would "rain blood" in revenge. Already under pressure over Iran's nuclear program, President Hassan Rouhani denied all allegations. However, a 2020 tweet from Rouhani in response to threats by American president Donald Trump turned some heads.

Professor Robert Black told Indian magazine The Week that he believed the tweet indicates that Lockerbie was a response to Iran Air 655. Jim Swire, father of Lockerbie victim Flora Swire, called this an admission of guilt in an interview with The Times. As of now, no investigations into the tweet or its possible meaning have taken place. Ultimately, Iran's role is still unclear, although the role of a Palestinian group makes sense, in light of the warning that was phoned into Helsinki in 1988. American intelligence services have mostly sidelined the Iranian angle and have pursued the Libyan angle further.

New charges, new suspects, but still no closure

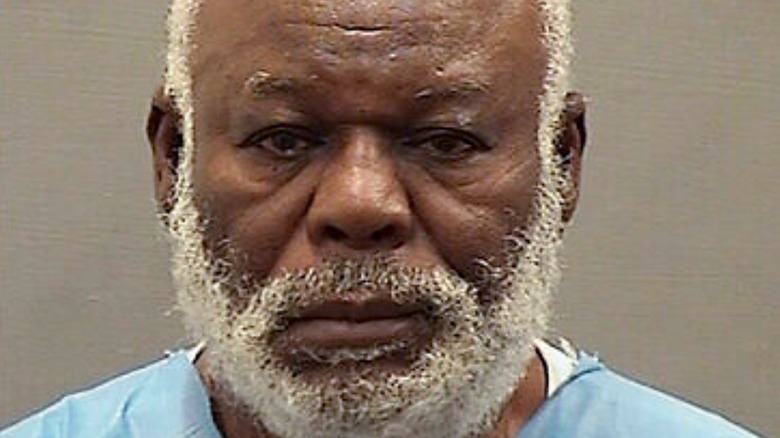

The latest development in the Lockerbie Bombing case came on December 21, 2020, the 32nd anniversary of the bombing. Attorney General William Barr and the U.S. Department of Justice announced new charges against a third Libyan currently incarcerated in his home country. The DOJ identified the "former senior Libyan intelligence official" as Abu Agela Mas'ud Kheir Al-Marimi but no other information was provided at the time.

The Lockerbie case has taken numerous twists and turns. When justice appeared served, it was revealed that special interests and economic expediency had tainted the trials of the suspects. Abdelbaset al-Megrahi's family has continued to fight his conviction posthumously, and on January 15, 2021, Scotland rejected an appeal to vacate al-Megrahi's conviction.

Suspect extradited to U.S. in 2022

When Attorney General William Barr indicted Abu Agila Mas'ud al-Marimi in 2020, the suspect was still in Libyan custody and needed to be extradited to face trial, per the AP. But, his sudden appearance in the United States in 2022 raised questions about how exactly he arrived there. In 2021, the Libyan government in Tripoli said it was open to collaboration on al-Marimi's extradition -– except as ABC noted, there was no extradition treaty.

U.S. officials have not issued a comment on the matter, and many outlets have simply said he was "extradited." But as noted in the AP, it is possible that American agents (or someone else working in tandem with the U.S. government) may have kidnapped al-Marimi and taken him to the states to face trial. The only evidence currently available is a Libyan report and claims from al-Marimi's family that Tripoli looked the other way regarding the kidnapping — as implied by government silence on the suspect's disappearance. Regardless, his presence in America is confirmed, and he has made his first court appearance.

Al-Marimi is the first Lockerbie suspect to appear in U.S. court and faces two counts of destruction of an aircraft causing death and one count of destruction of a commercial vehicle causing death, per ABC. While both of these could carry the death penalty, the Biden administration DOJ has said it will seek life imprisonment instead should he be found guilty. For Lockerbie relatives, it presents a chance to finally find closure on a case that has dragged on for over 30 years, with suspect after suspect but still no firm conviction that the perpetrators are behind bars.