What Really Happened During The Bataan Death March

In the Philippines, American forces suffered one of their largest military defeats in the Battle of Bataan during World War II. After their surrender, tens of thousands of soldiers were taken prisoner by Japanese forces and forced to march to their POW camp.

Known as the Bataan Death March, ThoughtCo describes how thousands of Filipino and American soldiers died during the march to the prison camp, as well as their subsequent imprisonment. And despite the fact that thousands of Filipinos had been promised citizenship in exchange for their service in the war, few who survived the Death March received what the United States government had promised them.

Although some of the Japanese officials who ordered the death march were convicted during the Manila War Crimes trials, as with Japan's biological warfare during WWII these war crimes were played down. As a result, few are aware of what POWs were subjected to in the Pacific. Here's what really happened during the Bataan Death March.

Recruitment in the Philippines

Even before joining World War II, the U.S. put troops in the Philippines to "protect its main Pacific possession," since the Philippines was a U.S. colony at the time. And within hours of attacking Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Japanese forces started an aerial attack on American forces in the Philippines.

According to The Kahimyang Project, the surprise attack on the Philippines started some 10 hours after Pearl Harbor was attacked. American forces in the Philippines started making moves to defend the archipelago, following the command of Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

However, only about 20% of the troops were Americans. Priceonomics writes that President Franklin D. Roosevelt promised Filipinos "U.S. citizenship and full veterans benefits" if they joined the war effort against the Japanese. However, this offer was withdrawn by President Harry S. Truman in 1946, and as a result, "only four thousand Filipino war veterans, out of an estimated 200,000 who survived the war, were able to get citizenship before the retraction was signed into law."

Out of roughly 150,000 soldiers, 120,000 were Filipino and the remaining 30,000 came from the U.S., "some of whom were Filipino Americans." Known as the United States Armed Forces in the Far East, or USAFFE, these were the Allied forces initially commanded by MacArthur in the Philippine campaign. By 1942, the USAFFE was reorganized into the United States Forces in the Philippines, or the USFIP and Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright assumed overall command.

The Battle of Bataan

As Japanese forces attacked the Philippines, Allied soldiers realized that they were severely under-matched. The Filipino defense forces were severely under equipped, and those who had weapons hadn't even fired their guns before

Priceonomics writes that "most troops carried either Enfield 17 rifles and Springfield 03s — which dated from 1917 and 1903, respectively. They had only about 20% of their artillery requirements. Their uniforms were worn-out and second-hand, the soles of their shoes quickly wore thin. This poverty even extended to food."

Over the course of several months, USAFFE fought back against the Japanese offensive while continuing to "suffer from a critical shortage of key supplies," according to ThoughtCo. By the beginning of April, the food shortage was so severe that "survivors recalled eating an officer's polo pony, then even iguanas, snakes and jungle insects and plants," writes the Atomic Heritage Foundation. Out of the four months of fighting, most of those months were spent on half-rations at most. Amidst the gunfire and bombing, soldiers also succumbed to dysentery and malaria due to the medicine shortage.

Despite everything, Gen. Douglas MacArthur ordered his men to continue fighting. However, knowing that the soldiers were at death's door, Maj. Gen. Edward P. King defied his orders and reached out to the Japanese to negotiate a surrender.

The Allies surrender

Disobeying the orders of Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Maj. Gen. Edward P. King met with Maj. Gen. Kameichiro Nagano on April 9, 1942. That day, the Allied forces at Bataan surrendered.

According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, initially some 58,000 Filipino soldiers and 12,000 American soldiers surrendered, since the surrender didn't include the USFIP forces "on Corregidor and elsewhere in the Philippines," writes ThoughtCo. But after Corregidor fell on May 7, Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright and all the remaining Allied forces in the Philippines surrendered.

During the Battle of Bataan, roughly 10,000 Allied forces were killed and 20,000 were wounded, compared to 7,000 killed and 12,000 wounded on the Japanese side. In addition, between 58,000 and 63,000 Filipino soldiers and 12,000 American soldiers who were a part of USFIP were taken by the Japanese as prisoners of war,

Out of these 75,000 prisoners of war, at least30% were "sick or wounded" at the time of their surrender. And estimates of the number of POWs reach as high as 80,000.

Moving the POWs

After the Allied forces at Bataan surrendered, the Japanese decided to move the Filipino and American POWs from the southern end of the Bataan Peninsula to the north. However, according to "World War II in the Pacific," by Stanley Sandler, since some of the troops didn't surrender until April 11, the Filipino and American POWs were still being moved to Balanga up to a week after the surrender. Some were collected from as far down on the peninsula as Mariveles.

Forced to walk eight miles from Bataan to Balanga, "many perished along the way from heat and exhaustion. In addition, the Japanese often bayoneted any POWs who fell behind or were unable to march." From Balanga, reports Smithsonian Magazine, the plan was to move the Filipino and American POWs to San Fernando, 31 miles to the north.

Originally, Maj. Gen. Yoshikata Kawane had intended to move at least 25% of the POWs by truck, but this plan had been made under the assumption that only 25,000 soldiers would surrender. As a result, the majority of the 75,000 Filipino and American POWs were forced to walk the 31 miles from Balanga to San Fernando. Overall, some of the POWs were forced to walk almost 63 miles in total.

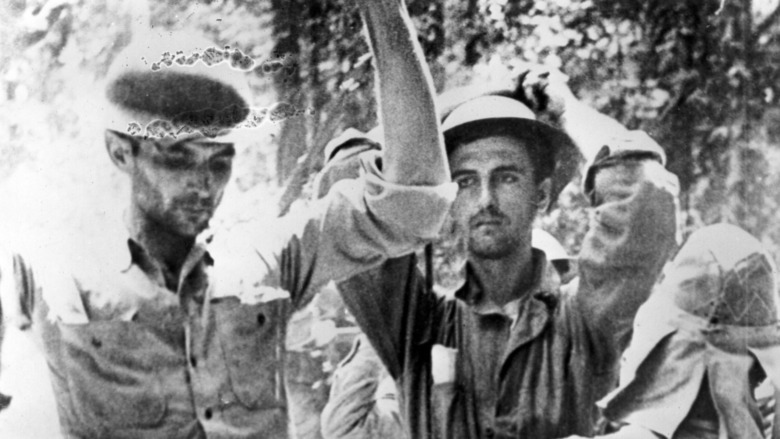

The Bataan Death March

The Japanese plan was to move the Filipino and American POWs to San Fernando, after which point they'd be put on a train, taken to Capas, and then marched to POW Camp O'Donnell. After being divided into groups of at least 100, the Filipino and American POWs were assigned Japanese guards and made to march. Over the course of a week, they marched with little-to-no rest, without being given any water or food.

According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, the Bataan Death March "was called the death march, because of the way they killed you. If you stopped walking, you died. If you had to defecate, you died. If you had a malaria attack, you died. It made no difference what it was; either they cut your head off, they shot you, or they bayoneted you. But you died, if you fell down."

Many of the Filipino and American POWs were suffering from illnesses, malnutrition, or injuries, but anyone who fell behind was executed. According to ThoughtCo., the group of Japanese soldiers who lingered behind to kill stragglers was known as the "buzzard squad."

Nolisoli writes that "some of the soldiers fought for survival by drinking the water where carabaos wallow." Lester Tenney, a survivor of the Bataan Death March, recalls how "we would see that and spread the scum along the side and just drink the water. The result was dysentery, real bad dysentery."

Tortured along the way

During the Bataan Death March, Filipino and American POWs were also subjected to various kinds of torture. Sometimes, the Japanese soldiers would randomly beat them with their rifles or use their bayonets to stab them as they passed by, says ThoughtCo.

When the Filipino and American POWs weren't being forced to march, they were tortured through "the sun treatment," which involved making the POWs stand in the direct sunlight for hours on end. On other occasions, POWs were pushed in front of vehicles. Military Times writes that there are reports that the Japanese soldiers took the dog tags from deceased Filipino and American POWs and cast them onto the side of the road before burial. However, this was potentially done "to keep the U.S. from identifying the dead."

There were a handful of food stops along the way, but other than some rice balls, the majority of the Filipino and American POWs went without food. There are reports that Filipino civilians gave food to the marching POWs, but there are conflicting accounts as to whether or not this was allowed by the Japanese soldiers.

Although American doctors were allowed to set up a first-aid station in Lubao, one of the feeding points, they were given no medical supplies, according to "World War II in the Pacific." In Lubao, some of the more seriously injured and ill were allowed to rest, but after a couple of days they were forced to resume their march.

A 45-mile train ride

When the Filipino and American POWs finished the first leg of their march in San Fernando, they were packed into trains for the second leg of their journey. Nolisoli writes that for the 25-mile journey from San Fernando to Tarlac train station, the POWs were "packed into steel train boxcars."

Although they were no longer forced to march, the Filipino and American POWs continued to die in the unventilated train cars from heat and exhaustion.

Over 60,000 people were crammed into six to seven boxcars. In "The Bataan Death March," by Robert Greenberger, one survivor recounts how "they packed us in the cars like sardines, so tight you couldn't sit down. Then they shut the door. If you passed out, you couldn't fall down. If someone had to go to the toilet, you went right there where you were." At one point when the train stopped, Filipino civilians tried to throw food into the train cars since the Japanese soldiers would beat them off if they tried to get close. But "we never got the food."

Arriving at O'Donnell

After getting off the train at Capas, Tarlac, those who survived the harrowing journey were forced to resume marching once again. After nine miles, says Nolisoli, the Filipino and American POWs finally arrived at Camp O'Donnell. "Nicknamed Camp O' Death," POWs at the camp continued to die from malnutrition and illnesses. According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, Minister of War Hideki Tojo had proclaimed that "A POW who does not work, should not eat," and the sick and wounded suffered especially from this mentality.

Although there was a hospital unit, it was known as "zero ward" because those who went there had "zero hope."

Torture was prevalent at the POW camp as well, and one of the survivors of Camp O'Donnell later testified that medicine and food were purposefully withheld from POWs, writes author Sarah Kovner. "According to one account, men who had collapsed from exhaustion were buried before they were actually dead."

Thousands continued to die at the prison camp, and few tried to escape. Prisoners were put into groups of 10, and if one of them tried to escape, they would all be executed.

How many survived?

By the time the Filipino and American POWs arrived at Camp O'Donnell, only about 54,000 out of the 72,000 original POW soldiers remained, writes author Robert Greenberger. It's estimated that between 7,000 and 10,000 people died during the march, reports the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, and those unaccounted for were believed to have escaped into the jungle. However, the exact number of deaths is ultimately unknown, so it's possible that the death toll is as high as 20,000 for the march alone. What is known for sure is that a majority of the deaths were Filipino soldiers. According to PBS, it's estimated that between 9,000 and 16,000 Filipino soldiers died and between 650 and 2,300 Americans died during the Bataan Death March.

For some, the march took six days, but for others it took over a week to make the full trek to Camp O'Donnell.

In addition, the death toll for Filipino soldiers was staggeringly higher than for American soldiers. According to the Provost Marshal Report, at Camp O'Donnell at least 22,000 Filipino POWs and 1,500 American POWs died "during the seventy-one days of O'Donnell's operation." Often, the mass graves were so shallow that "you could see legs, hands, or feet sticking out of the little dirt used to cover them."

The death rate at Camp O'Donnell was so high that "the Japanese ordered the camp closed on 16 May 1942," although it wouldn't be completely closed until January 20, 1943.

The Hell Ships

Not all of the Allied POWs were kept in prison camps. Some were herded into merchant ships and moved closer to Japan, where they would be sent to do heavy labor where there were labor shortages.

These merchant ships were known as "hell ships" and like the train boxcars, there was barely any room to stand or even breathe, writes the Atomic Heritage Foundation. The hell ships traveled from the Philippines to mainland China, Korea, and Japan, sometimes taking upwards of a month for the journey.

The National Archives also writes that since the merchant ships were unmarked, U.S. submarines and planes considered them a target. It's estimated that over 126,000 Allied POWs were transported in the merchant ships, and "more than 21,000 Americans were killed or injured from 'friendly fire' from American submarines or planes ..."

Hundreds more died on the ships from starvation or suffocation. The Washington Post writes that "others went mad and were killed by fellow prisoners. Still others were shot by Japanese guards."

Surviving the march, torture, and an atomic bomb

When Army Sgt. Joe Kieyoomia was captured in the Philippines in 1942, he didn't realized what was going to be in store for him over the next three-and-a-half years. Deseret News writes that Kieyoomia was a member of New Mexico's 200th Coast Artillery unit and after surviving the Bataan Death March, he was sent to the Japanese mainland after a week at Camp O'Donnell.

According to We Are The Mighty, although Kieyoomia was Diné, or Navajo, the Japanese soldiers believed that he was Japanese-American and tortured him daily as a result. "I told them I was Navajo [but] they didn't believe me. The only thing they understood about Americans was black and white. I guess they didn't know about Indians."

After several months, the Japanese soldiers decided to believe Kieyoomia and tried to get him to help them break the code used by the Navajo Code Talkers. But since the code was only known by those who had developed it, Kieyoomia's translations were basically useless. The Japanese guards continued to torture Kieyoomia, and when he tried to starve himself to death, the "guards beat him until he ate."

On August 9, 1945, Kieyoomia was in a prison cell in Nagasaki when the Amercians dropped their second atomic bomb on the city. Kieyoomia miraculously survived due to the concrete walls of the prison cell, and after several days he was finally freed by a Japanese officer.

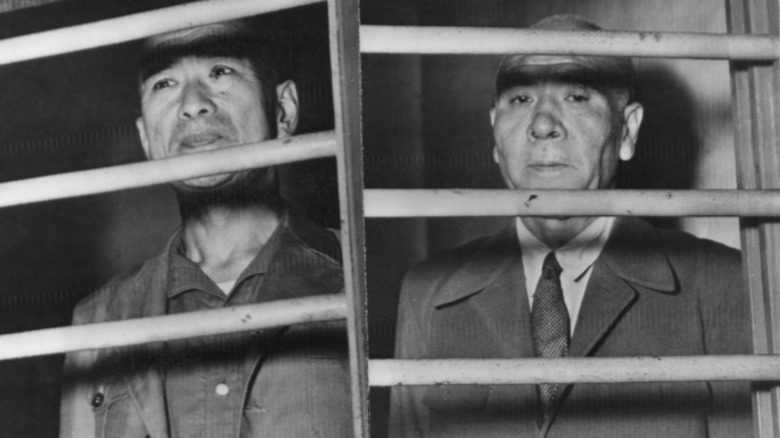

The legacy of the Death March

After Japan surrendered, and the POWs were liberated, Lt. Gen. Homma Masaharu was charged for the atrocities that were committed during the Bataan Death March. According to ThoughtCo., since Masaharu was in charge of Japan's invasion of the Philippines and had been the one to order the move to Camp O'Donnell, he was considered to be responsible.

Although Masaharu acknowledged that he was responsible "for his troops' actions," he claimed that he'd never ordered them to act in such a cruel manner and had no knowledge of the atrocities. However, the U.S. military tribunal found him guilty. PBS writes that "according to historian Philip Piccigallo, Homma was convicted for the actions of his troops rather than for directly ordering atrocities." Masaharu was executed by firing squad on April 3, 1946.

Nolisoli reports that 138 obelisk memorials known as Death March markers have been built along the path that the POWs marched. However, these markers are sometimes damaged or uprooted by construction projects.

Meanwhile, Filipino veterans wouldn't be offered citizenship until 1990, and they wouldn't receive any kind of veterans benefits until 2009, when a lump sum was paid out to surviving Filipino and Filipino-American veterans.