The Tragic History Of The Rwandan Genocide

In 1994, almost 1 million people were murdered in Rwanda after Hutu extremists ordered the execution of all Tutsi and Hutu moderates. Although the killings lasted just 100 days, they left an indelible mark on Rwandans across the region.

During colonial rule, ethnic identities had been categorized and solidified, and following Rwandan independence, there were frequent ethnic cleansings in the region. As Rwanda erupted into a civil war in the 1990s, the genocide came at the tail end of the ethnic cleansings. And as if the genocide wasn't horrific enough, the international community contributed to the horror by doing next to nothing. Although several world leaders later apologized for their negligent role during the Rwandan genocide, this wouldn't be the last time that the international community turned a blind eye to genocide.

Over 25 years later, tens of thousands continue to suffer from a legacy of trauma, even those who were born after the genocide. And although the government has sought to subdue ethnic tensions, this "enforced unity" is coupled with oppression and suppression of dissent. This is the tragic history of the Rwandan genocide.

Rwanda before colonization

Before Europeans invaded what is now known as Rwanda in the 19th century, the people of Rwanda differentiated each other through a clan system rather than ethnic divisions. There were approximately 18 clans, according to "The Unity of Rwandans," and those who are now considered to be Hutus, Tutsis, or Twas were spread among the various clans. During this time, the distinction between Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa people was primarily occupational, though Twa were generally marginalized. "Cattle-herders, soldiers and administrators were mostly Tutsi, while Hutu were farmers," according to "The International Response to Conflict and Genocide."

It was during the reign of Kigeli IV Rwabugiri, which lasted from 1860 to 1895, that these "ethnic" differences began to be highlighted during the centralization of his power. According to "We Cannot Forget," edited by Samuel Totten and Rafiki Ubaldo, "With the arrival of central authorities, lines of distinction were altered and sharpened, as the categories of Hutu and Tutsi assumed new hierarchical overtones associated with proximity to the central court — proximity to power."

These classifications were further underlined through the hierarchical patron/client relationship, also known as ubuhake, which existed at the time. "Most Tutsi were clients and some Hutu patrons. At the top, however, there were always Tutsi and at the bottom always Hutu and/or Twa," per "The International Response to Conflict and Genocide."

Under colonial rule

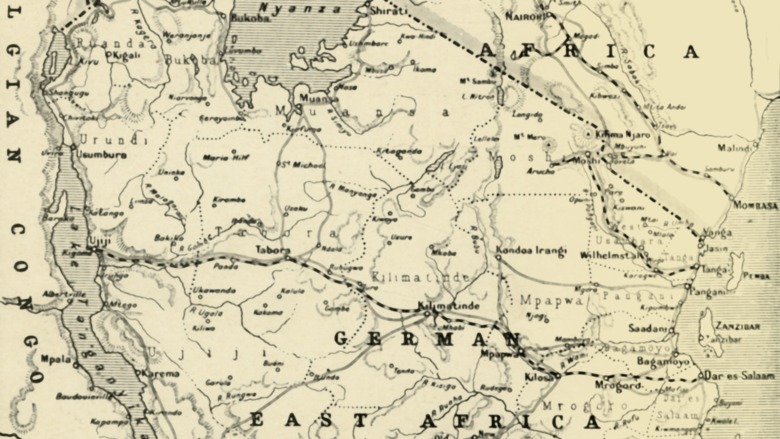

During German and Belgian colonization, this institutionalized relationship was reinforced, made rigid, and exploited. According to "Phrenology and the Rwandan Genocide," British explorer John H. Speke was one of the first to use phrenology to introduce the myth of racial superiority. In 1864, he wrote that "the Hutus were a 'primitive race,' while the Tutsi 'descended from the best blood of Abyssinia' and were, therefore, far superior."

This myth was further disseminated by the Belgian colonial authorities, who introduced Rwandan ID cards in 1933, which included whether a person was Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa. A census was also organized by the colonial administration to make sure that everyone was categorized. European scientists were brought to Rwanda specifically to classify people based on their body measurements and craniofacial features. Those who were considered to more closely resemble Europeans were seen as more "aristocratic by nature."

According to "The International Response to Conflict and Genocide," although traditionally, Hutu and even Twa "exercised certain political power, albeit at lower levels, the 'Tutsification' of the 1930s resulted in a monopoly of political and administrative power in the hands of Tutsi." Over the next 20 years, Tutsi were granted better education opportunities and jobs as well as being able to hold positions of power.

The Rwandan Revolution

After 60 years of colonial rule, the Tutsi monarchy which had ruled throughout the colonial period was overthrown. However, the Hutu elite that took over were ultimately still backed by the Belgium administration.

According to "The International Response to Conflict and Genocide," Belgian authorities adopted a "de facto pro-Hutu policy" and seemed to condone the widespread violence during the Hutu uprising. In some places, Belgium set up military guards that were 85-percent Hutu and 15-percent Tutsi.

During the Rwandan Revolution, which lasted from 1959 to 1961, at least 20,000 Tutsis were killed, and thousands more became refugees in Burundi, Tanzania, and Uganda. This confrontation came out of the fact that before the revolution, power was centralized with the chiefs and sub-chiefs, who were primarily Tutsi. The idea of Hutu inferiority was so ingrained in Rwandan society that even the most impoverished Tutsi were still treated better than those seen as Hutu.

Led by President Grégoire Kayibanda and the MDR-Parmehutu, the First Rwandan Republic was established on July 1, 1962. PBS writes that by the mid-1960s, it's estimated that half of the Tutsi population had fled Rwanda. "For their part, European missionaries and colonial officials deplored the violence even as they blamed much of it on Tutsi exile militias, attributing the Hutu reactions to uncontrollable 'popular anger,'" writes Oxford University Press.

Waves of ethnic cleansings

Over the next 25 years, there were numerous waves of ethnic cleansings in both Rwanda and its neighboring Burundi, which had been part of the Ruanda-Urundi colony and had established its independence in 1962 as well.

According to Oxford University Press, in December 1963, a militia of Tutsi exiles invaded Rwanda. Although they were quickly suppressed by both Rwandan and Belgian army forces, the Rwandan government swiftly retaliated, and "in the weeks that followed, local government 'self-defense' units executed upwards of 10,000 Tutsi civilians in the southern Rwandan province of Gikongoro."

Massacres resumed in 1967, and in 1973, another wave of killings was accompanied by a purge of Tutsi people from universities. The pogroms also occurred at "several Catholic seminaries, and a multitude of secondary schools and parishes," per Oxford.

Ethnic cleansing also occurred in Burundi, and after a failed coup d'état in May 1972, over 200,000 Hutu people were murdered over the course of three months by Burundi's Tutsi-dominated military. In 1988, roughly 50,000 Hutu refugees fled from Burundi to Rwanda after another wave of massacres.

Civil war in the 1990s

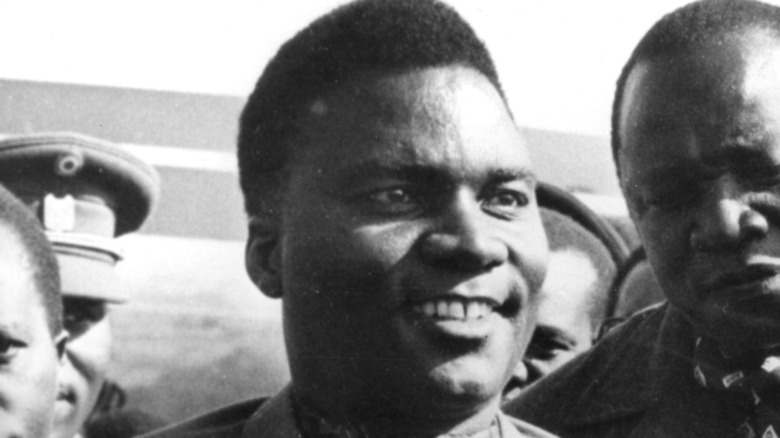

After a military coup deposed President Kayibanda in 1973, the leader of the coup, Juvénal Habyarimana, seized control and set up a one-party state. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the military dictatorship limited the number of Tutsi people in public service employment. It isn't until July 1990 that President Habyarimana allowed for the creation of multiple political parties.

But in October 1990, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), composed of between 5,000 and 10,000 Tutsi forces, invaded Rwanda from Uganda, setting off the Rwandan Civil War. The BBC writes that since President Habyarimana was losing popularity by the 1990s, he "chose to exploit this threat as a way to bring dissident Hutus back to his side, and Tutsis inside Rwanda were accused of being RPF collaborators."

Although the Arusha peace accord was signed in August 1993, it did little to stop the fighting and unrest. And when President Habyarimana was assassinated on April 6, 1994, Hutu extremists went into overdrive.

President Habyarimana and Burundian president Cyprien Ntaryamira were killed when Habyarimana's jet was struck by two missiles. No one knows who exactly the assassins were, but the Rwandan government immediately blamed the Rwandan Patriotic Front. However, according to The Guardian, different reports have come to conflicting conclusions as to whether or not the RPF was actually responsible, with some evidence suggesting that Hutu extremists were responsible for the attack.

Organized murders begin

Starting in Kigali, organized killings began in response to what is thought to be an attack against the Hutu after the assassination of President Habyarimana. According to the University of Pennsylvania, although many Tutsi people were murdered that night, victims also included Hutu who were opponents of the National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development (MRND) and the Coalition for the Defense of the Republic (CDR).

By the following day, PBS reports that roadblocks were established by the Rwandan Armed Forces and Hutu militia, which was formed out of the youth wing of the MRND known as the Interahamwe. At the same time, they went door-to-door killing thousands of Tutsi and moderate Hutu politicians. Thousands were murdered in the first 48 hours. As PBS writes, "Some U.N. camps shelter civilians, but most of the U.N. peacekeeping forces (UNAMIR — United Nations Assistance Mission in Rwanda) stand by while the slaughter goes on. They are forbidden to intervene, as this would breach their 'monitoring' mandate."

After President Habyarimana's assassination, Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana took over as head of state and of government. Although U.N. soldiers were assigned to protect her, as she was part of the Republican and Democratic Movement (MDR) opposition party, Uwilingiyimana and her husband were murdered along with the 10 Belgian soldiers on April 7, 1994.

Weeks of killing

Over the course of 100 days, between 800,000 and 1 million Tutsi and moderate Hutu were murdered by Hutu militias and the Rwandan Armed Forces. The killings were also organized, and lists of people were handed out to the militias in addition to weapons.

"Neighbours killed neighbours and some husbands even killed their Tutsi wives, saying they would be killed if they refused," writes the BBC. At this time, the ID cards from the colonial period that denoted ethnicity were still being used as well, so the roadblocks were used to check identification, and any man who was a Tutsi was promptly murdered.

The Hutu extremists also set up a radio station, RTLM, where they would read out the names of prominent people to be killed. Propaganda was also circulated with both the radio and the newspapers, "urging people to 'weed out the 'cockroaches,'" per the BBC.

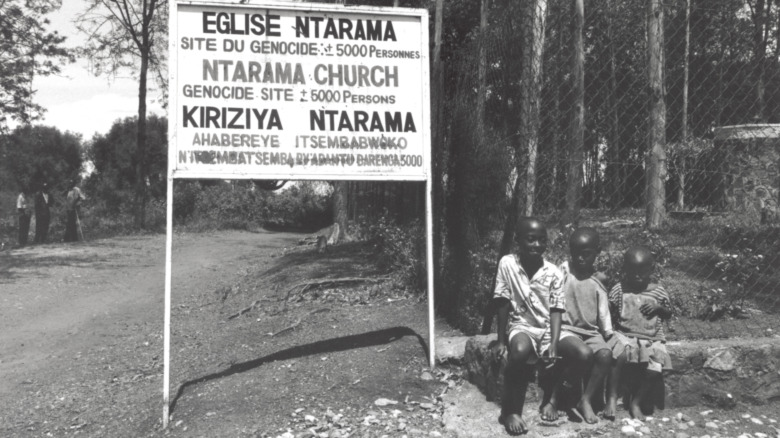

People from all walks of life participated in the slaughter, including priests and nuns who murdered those seeking shelter in their churches. According to Reuters, "Seventy percent of the Tutsi population was wiped out, and over 10 percent of the total Rwandan population."

Avoiding the word 'genocide'

During the Rwandan genocide, on April 30, 1994, the U.S. Security Council passed a resolution that acknowledged and condemned the killings but explicitly avoided using the word "genocide." According to PBS, "had the term been used, the U.N. would have been legally obliged to act to 'prevent and punish' the perpetrators."

The Conversation writes that at the time, there were roughly 2,500 U.N. peacekeepers in Rwanda, having been sent there to help implement the 1993 Arusha Agreement. But when the massacres started, the troops were ordered only to evacuate foreigners and ended up becoming bystanders to genocide. And by the time the United Nations got around to acknowledging the killings, they'd already voted unanimously to withdraw almost all of the UNAMIR troops. So instead of 2,500 U.N. bystanders, there were only 270.

It isn't until May 17 that the U.N. finally decided to send over 5,000 to Rwanda, noting in their resolution that "acts of genocide may have been committed." The deployment of these forces was further delayed due to arguments over who would pay for the forces and supply them with equipment. Ultimately, U.N. troops wouldn't arrive in Rwanda until mid-July, by which point the genocide had come to an end.

Dumping in the Kagera River

Before the Rwandan genocide, Leon Mugesera, at the time the vice president of the MRND, gave a speech on November 22, 1992, in which he said that Tutsi people should be murdered and have their bodies dumped into the rivers of Rwanda. Even before the genocide started, an arrest warrant was issued against Mugesera, leading him and his family to flee to Canada. However, by that point, the damage had already been done.

Tragically, thousands of Tutsi who were murdered during the Rwandan genocide ended up being drowned or dumped in the Kagera River, also known as the Akagera River. During his speech, Mugesera had claimed that Tutsi came from Ethiopia, reminiscent of the Abyssinian heritage that the Europeans claimed in Tutsi, and identified the Kagera River as a place where the Tutsi could be sent "back to Ethiopia," reports The New Times.

The Associated Press reports that every day, between 15 and 50 bodies were thrown into the river. Some organizations estimated that at one point, upwards of 25,000 bodies were floating in Lake Victoria.

Foreign involvement and lack thereof

Three days after the killings started in April, French, Belgian, and American citizens were airlifted out of Rwanda. However, nothing was done to help protect Rwandans. According to PBS, even Rwandans employed by Western governments were abandoned.

The Atlantic writes that in addition to prioritizing its own citizens, the United States actively made the genocide in Rwanda worse: "It led a successful effort to remove most of the UN peacekeepers who were already in Rwanda. It aggressively worked to block the subsequent authorization of UN reinforcements. It refused to use its technology to jam radio broadcasts that were a crucial instrument in the coordination and perpetuation of the genocide." Plus, according to The Guardian, during this time the United States simultaneously "ramped up military and development aid to Museveni [the president of Uganda who was assisting the RPF] and then hailed him as a peacemaker once the genocide was underway."

In 2021, a French government inquiry ruled that France had been "blind" to the genocide in Rwanda and found that France had failed in its "political, institutional, intellectual, ethical (and) moral" responsibility. Meanwhile, another report commissioned by Kigali calls France a "collaborator" with the extremist Hutu regime that was responsible for the genocide and notes that "French authorities refused to cooperate with their inquiry or turn over critical documents pertinent to their investigation."

The women who survived the Rwandan genocide

Sexual violence was also pervasive during the genocide, and thousands of women were raped and, if they weren't murdered afterward, forced into marriage or sold into slavery. Sometimes, after being raped, women were subjected to further physical violence and mutilation.

According to a survivor who spoke to The New Times, "For four years after the genocide I did not talk, I did not open my mouth, except to speak to one lady, one of the five who crawled away from the roadblock together with whom I shared the same experiences. We used to go and lock ourselves inside a house and just cry the whole day."

Upwards of 250,000 victims were raped, and it's unknown exactly how many children were born as a result, Reuters reports. Many of the women and their children also ended up testing positive for HIV as a result of being raped. Although survivors were provided with basic needs after the genocide, "no one paid attention to the trauma," and as of 2018, at least 35 percent of survivors reported symptoms of PTSD.

The RPF capture Kigali

Throughout the genocide, the Tutsi-dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front continued to advance into Rwanda, and on July 4, 1994, the RPF took control of the capital of Kigali after several days of fighting. As the Rwandan government collapsed and a ceasefire was declared, it became clear that the RPF was successful.

In addition to the deposed Hutu government, 1-2 million Hutu fled to the Democratic Republic of the Congo as refugees from Rwanda. There were also over 100,00 Burundian Hutu who were fleeing the military regime in Burundi. However, according to Stanford University, tens of thousands of the Rwandan refugees were army officers who were part of the defeated regime, or members of the Interahamwe militia who were directly responsible for the genocide.

By July 15, the genocide was considered to be over, as the Rwandan Patriotic Front took over and established "an interim government of national unity in Kigali," according to PBS.

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

Located in Tanzania, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda was the first international tribunal since the 1945 Nuremberg Trials. The tribunal was established in 1995 and held over 70 trials until it was closed in 2015.

According to DW, 61 people were convicted through the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. Several others were charged through Gacaca, the traditional courts in Rwanda. Despite the fact that many journalists, politicians, and military chiefs were brought to justice, none of the Rwandan Patriotic Front members were investigated, despite the fact that "the ICTR had a mandate to also prosecute former Tutsi rebels, some of whom now occupy leading positions in Rwanda."

The trials also did little to serve Rwandans and didn't seem concerned with including the survivors of the genocide in its process. According to the Humanitarian Practice Network, "particularly in the early ICTR stages, minimal outreach and public relations took place in Rwanda. Reportedly contacts between ICTR staff and NGOs or genocide survivors associations were not encouraged."

The legacy of the Rwandan genocide

Although the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda has been closed, many continue to advocate for the prosecution of the "remaining perpetrators and backers of the genocide."

According to Spiegel, after President Kagame took office in 2000, he "banned anyone from publicly referring to ethnic groups and has had all references to ethnicity removed from passports." However, many consider these changes to be superficial. "Just because nobody talks about ethnic tensions, doesn't mean there are no tensions anymore," says Professor Christopher Kayumba. In 2013, President Kagame's government pushed a program known as Ndi Umunyarwanda, or "I am Rwandan," which is "designed to rebuild trust by encouraging individuals to tell the truth about what happened in the genocide."

However, this call for unity is accompanied by suppression of dissidents as President Kagame refuses to relinquish power. And according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, although "some journalists say they have come to accept censorship as necessary to avoid a return to the ethnic battles," they also face limitations in what they're allowed to say about the military or the president, and many journalists resort to self-censorship.