The Tragic History Of The 20th Century Armenian Genocide

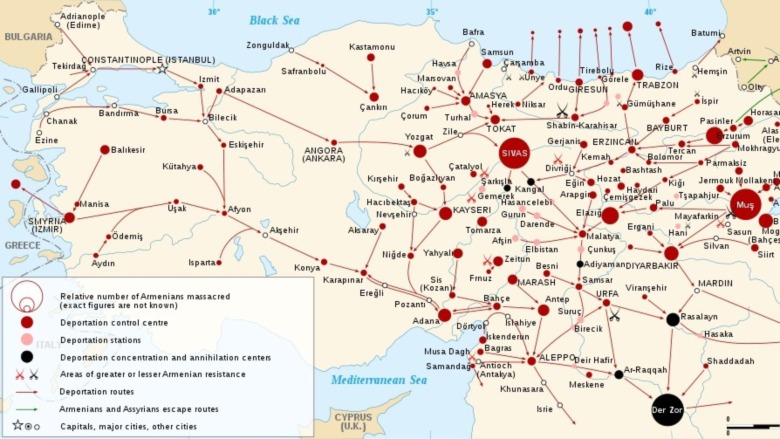

From 1915 to 1918, the Young Turk regime engaged in a systematic extermination of the Armenian people within the Ottoman Empire's borders. In addition to waves of massacres across the empire, hundreds of thousands of Armenians were deported to concentration camps in the Syrian Desert where many lost their lives to starvation and disease.

Known as the Armenian Genocide, this wasn't the first time that Armenians were persecuted in the Ottoman Empire. However, the scale of the killings was so vast that in Armenian literature the genocide is referred to as "Meds Yeghern" or "Great Calamity." Raphael Lemkin, who coined the word "genocide," even noted that his idea of what genocide entailed was heavily influenced by learning about the Armenian Genocide after one of its perpetrators was assassinated in Berlin in 1922. The Armenian people weren't the only ones the Ottoman Empire targeted with a genocidal campaign. Greek and Assyrian people were also sought to be exterminated in a similar manner to the Armenian people.

Although courts in the Ottoman Empire acknowledged the genocide and prosecuted its perpetrators, the few convictions that occurred were ultimately suppressed by the subsequent Turkish government, which as of 2021 continues to deny its systematic slaughter of the Armenian people. This is the tragic history of the 20th century Armenian Genocide.

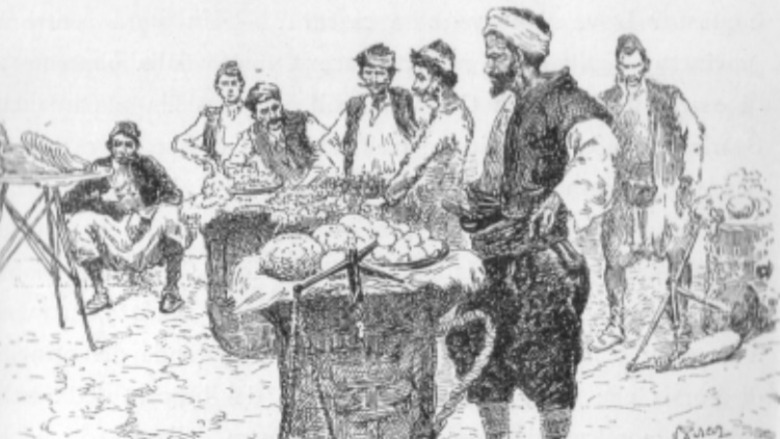

Armenians in the Ottoman Empire

In the Ottoman Empire, Armenian people were relegated to a second-class status. "The Armenian Experience" explains how in addition to being subjected to higher taxation, "Armenians were not allowed to ride horses or carry weapons and were prohibited from wearing certain colors. They did not have a right to lodge a complaint against a Muslim. Nor could an Armenian hold public office." According to the SPLC, Armenians weren't even able to testify in court.

This discrimination wasn't limited to Armenians. Non-Muslims such as Assyrians, Greeks, and Jewish people were also treated as second-class citizens and subjected to the millet system, which professed to maintain communal autonomy, but in fact just held citizens outside the law "while depriving them from all forms of political participation."

Since Armenians were denied the ability to participate in "the bureaucracy, the police, military, and court system," they went into crafts, commerce, and various economic sectors instead. However, according to Hetq, even these industries weren't free from Ottoman harassment. Markets in Van, Adana, and Kharpert suffered arson attacks, and "in 1908, the Ottoman authorities seized Armenian manufacturing centers in the town of Kharpert."

The Hamidian massacres

The 20th century genocide wasn't the first time the Armenians faced extermination in the Ottoman Empire. The Hamidian massacres, instigated by Sultan Abdülhamid II, lasted from 1894 to 1897 and resulted in the deaths of between 80,000 and 300,000 Armenians.

According to Timewise Traveller, by the 1880s there were roughly two and a half million Armenians living in the empire, and Sultan Abdülhamid II "perceived this as a direct threat to the Islamic character of the state, and the internal security of the Ottoman Empire." And after Armenians started protesting the heavy taxation and persecution they were experiencing, Sultan Abdülhamid II responded with violent suppression.

Soldiers and cavalry were dispatched to Armenian villages and "regardless of their stated purpose, the Hamidiye would go on to join in the massacre of the Armenians." These killings also weren't limited to Armenians. Greeks and Assyrians were also targeted in several massacres during these three years.

The Ottoman Empire enters WWI

As World War I started in the summer of 1914, the Ottoman Empire initially declared neutrality as it started negotiating with both sides. History Crunch writes that due to these negotiations, a secret Ottoman-German Alliance was established. Together, Germany and the Ottoman Empire were going to try to "trick Russia into attacking the Ottoman Navy and mak[e] it look like Russia had instigated war." Although, this plan failed when German commander Admiral Wilhelm Souchon attacked the Russian coast first, nevertheless, within two weeks the Ottoman Empire was officially at war with Britain, France, and Russia.

Throughout the war, the Ottoman Empire primary fought on the Middle East Front and the Balkans Front. And although there were victories, such as the Gallipoli Campaign, the empire was forced to admit defeat and sign an armistice in October 1918.

However, the Ottoman Empire's alliance with Germany would prove essential for the Armenian Genocide that was occurring simultaneously. According to DW, "Mauser, Germany's main manufacturer of small arms in both world wars, supplied the Ottoman Empire with millions of rifles and handguns, which were used in the genocide with the active support of German officers."

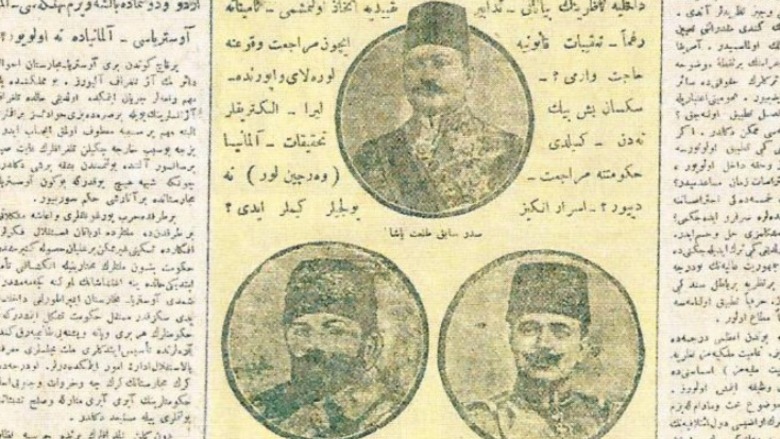

The Three Pashas

Five years before World War I, Sultan Abdülhamid II was deposed during the 1909 Young Turk Revolution. Although Mehmed V was set up as a figurehead, the empire was ruled by the Three Pashas: Mehmed Talaat Pasha, Ismail Enver Pasha, and Ahmed Cemal Pasha, who had been leaders of the revolutions. Many consider Talaat Pasha to be the "principal architect of the Armenian Genocide" since many of the orders decreeing the evacuation and deportation of Armenians bear his signature.

Initially, Armenian people in the Ottoman Empire supported the Young Turks, since they had "promised equality for all groups within the empire, including Armenians," according to Facing History. However, the Young Turks soon abandoned ideas of equality in favor of radical nationalism and homogenization, known as Turkification.

After bringing the Ottoman Empire into World War I, the Young Turks once again used the excuse of questioning the loyalty of their Armenian citizens after suffering a defeat to the Russians at the Battle of Sarikamish. Enver Pasha blamed the Armenians, and all the Armenian recruits in the Ottoman Army were disarmed, removed from active duty, and placed into labor camps in February 1915, writes the University of Minnesota. There, they were "compelled to dig their own graves before being shot." However, even before the war there had already been several attacks against Armenians, and in September 1914, weapons had been distributed to Muslim residents of Keghi with "the excuse that the Armenians there were unreliable."

Armenians in Van

From the end of 1914 to the spring of 1915, Armenian people across the Ottoman Empire faced raids and looting. Although the Young Turk regime later claimed that the Armenian people had staged a revolt, according to Ordered to Die, scholars "have concluded that the Turks themselves deliberately instigated the revolts by enforcing intolerable conditions on the Armenians. These acts included murder, rape, and lesser humiliations."

The most famous Armenian resistance against Ottoman oppression occurred in Van on April 19th, 1915, though there were several other shows of resistance in the cities of Diyarbakir, Erzurum, Bayburt, and Tortum over the following several months. Although these were used as justification for the massacres of the Armenian people, these were a response to the already occurring persecution. And "within the course of a few weeks, 51 Armenian villages disappeared from the map of Van forever."

During this time, orders were also given to massacre all Armenian men over the age of 12. Numerous witnesses, "including Americans and Germans with direct access to the ruling elite, claimed to have been told about similar orders." As Armenians in Van staged a defense against Ottoman slaughter and accepted Russian assistance, this was taken as pretext by the Young Turk regime to ramp up the systematic slaughter of the Armenians. But mass murders were well underway before the official start of the genocide, with more than 25,000 Armenian people already having been executed.

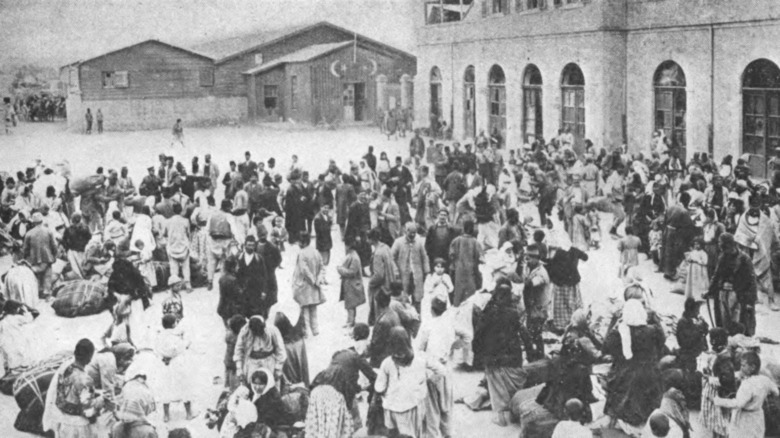

Rounding up activists and community leaders

Although the Armenian Genocide is considered to have officially begun on the night of April 24th, 1915, it's clear that there was systematic persecution of the Armenian people in the Ottoman Empire long before the events of 1915. On the night of April 23rd and over the course of the following day, over 200 Armenian activists, writers, and community leaders were rounded up by Ottoman police in Constantinople, today known as Istanbul, in an effort to exterminate Armenian leadership. During the next few weeks, over 2,000 Armenian people were deported from Constantinople "aboard trains that left Hyderpasa for Ankara." The deportations were justified with the claim the Armenian people were conspiring with the Russians against the Ottoman Empire, but there's little evidence to support this claim.

According to Grigoris Balakian, a Christian priest who was among those arrested, "It was as if all the prominent Armenian public figures—assemblymen, representatives, revolutionaries, editors, teachers, doctors, pharmacists, dentists, merchants, bankers, and others in the capital city—had made an appointment to meet in these dim prison cells." Although many ended up being executed, "those of us still alive envied those who had already paid their inevitable dues of bloody torture and death."

In 1915, the Young Turk regime also "passed new laws providing for the annexation of Armenian businesses and trades" and legitimized the seizure of the property of Armenian people. But some people didn't wait for their Armenian neighbors to get deported and robbed them outright.

Deportations into the desert

After arresting the Armenian intelligentsia, mass deportations began in full force. Armenian people from across the Ottoman Empire were marched to "relocation camps," though really they were just marched into the Syrian Desert. "The Armenian Genocide, 1915" explains how the final order for deportation was given by Talaat Pasha on May 23rd, 1915. Several days later, "in an attempt to camouflage the deportations as legal, Talaat drew up the temporary 'Dispatchment and Settlement Law.'" But by this point, deportations were well underway.

According to Words Without Borders, sometimes the march would take over a month along a trail of over 500 miles that was before long littered with corpses. In places like Cungus, "an untold number of Armenians were tossed to their deaths" into a crevice in the landscape. Often, Armenian men and boys were separated and executed while women and young children made up the majority of the marchers; sometimes older men survived long enough to make it to the camps. But a majority of Armenian men had already been conscripted to fight in World War I.

Government notices were put up informing Armenians to leave all of their belongings and that they would face legal action if they tried to sell anything. The notices also claimed that "on your return, you will get everything you left behind." In some places, Armenians were given a few days, while others only had a few hours to prepare for their exile.

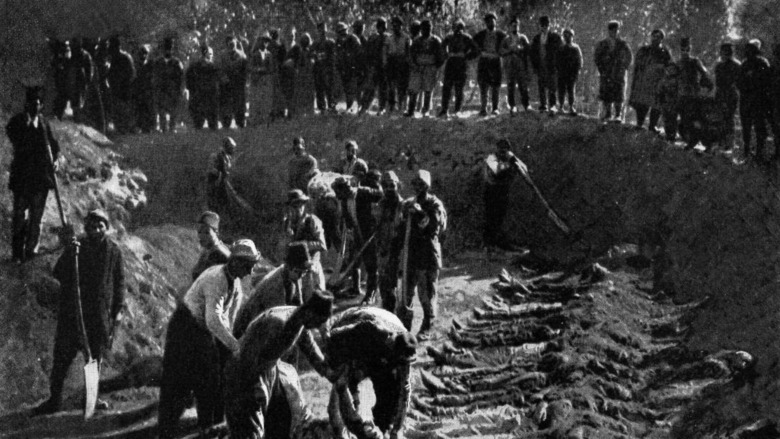

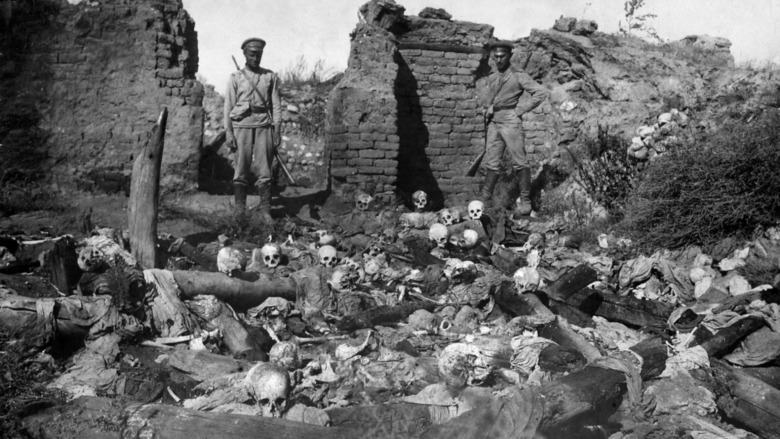

Mass executions

In addition to the hundreds of thousands of Armenians who died during the death marches across the desert from starvation, thirst, and disease, thousands were killed in mass executions. According to "The Armenian Genocide, 1915," when 40,000 Armenians were deported from Erzurum, executions along the way resulted in only 200 actually making it to Deir ez-Zor. In Diyarbekir, after the local Armenian population was forced out of town under the guise that they were being relocated, thousands of Armenian men were murdered and "thrown into a cave opening by Kurdish Ottoman forces." The University of Minnesota writes that along the death marches "massacres became more commonplace and widespread."

Bodies were dumped into the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers with such regularity that "they created problems for the local authorities in Syria and Mesopotamia" and even came up in letters from German diplomats in Aleppo. Bodies reportedly floated by for months and "it was sometimes necessary to use explosives to clear what were quite literally dams formed by the mass of floating bodies."

When bodies weren't thrown into caves or rivers, they were thrown into hastily dug trenches. At one point, subgovernors and gendarmerie commanders were threatened with court martial if they didn't dig trenches deep enough so that animals wouldn't bring the remains to the surface. And although there are some accounts of Armenians being protected by Turkish or Kurdish people, this was rare and came with high risks, as civilians were often hung for such a "crime."

Concentration camps in the deserts

Those who survived the executions and the death marches ended up in the Deir ez-Zor camps in the Syrian desert. These concentration camps were essentially open-air torture chambers where tens of thousands died from starvation and disease. There was no food and people were forced to survive by chewing grass and drinking "dirty water mixed with animal urine." According to "Modern Genocide," crimes and atrocities like "corruption, embezzlement, and abduction of women and children were commonplace as camp directors, local officials, guards, and others in positions of power preyed upon the civilian Armenians who were essentially pronounced fair game."

Before 1916, there were several camps along the Euphrates river as well. But after Talaat Pasha decided that "too many Armenians had survived the journey," more executions were ordered. In the spring of 1916, 40,000 Armenians at the Ras al-Ayn camp were murdered.

Although there were 200,000 Armenians at Deir ez-Zor during one of its peaks, when British forces invaded Syria in October 1918, only 1,000 Armenians remained alive at Deir ez-Zor. It's estimated that out of the two million Armenian people who lived in the Ottoman Empire at the start of World War II, up to one and a half million perished during the three year genocide.

What happened to the survivors of the Armenian Genocide?

Some of the women and children who survived the executions and the death march were eventually rescued by Arab people in the region. Others were forced into sexual slavery. Sometimes, women and young girls were picked out of the marchers and the caravans on their way to the camps, while in other places, homes or churches were made into brothels. Others survived by succumbing to the Turkification program and forced conversion. According to Al Jazeera, orphanages were set up where children were forced to "convert to Islam and change their names to Turkish ones."

Despite appearances, the Armenian genocide had little motivation in religion. The Young Turks themselves claimed to be secular and Muslims outside of the Ottoman Empire often tried to save Armenians during the genocide. Through contacts and word of mouth, many Arab families who had adopted the orphans returned them to their communities: "This was a very common theme; that the orphans would be 'lost' for a few years and then they would find their way back to their families. It happened to thousands of Armenians."

Many Armenian people ended up living outside of Armenia for decades until a decree from Stalin allowed their repatriation. Before World War I, at least 100,000 Armenian people had escaped from the Ottoman Empire to Iran or Russia. But "after March 1915, escape was no longer possible."

What happened to the perpetrators of the Armenian Genocide?

The Three Pashas were tried in absentia for their crimes against the Armenian people in post-war Ottoman courts between 1919 and 1920. Although they were found guilty and sentenced to death, all three had fled the country by that point. In the following years, Talaat Pasha was one of several perpetrators to be assassinated in Berlin as a part of Operation Nemesis, writes Armenian Weekly.

According to "Children as Victims of Genocide," there were several court martial trials, such as the one in Trebizond, where "some two-dozen Turks, including physicians, military officers, governmental officials, and merchants in the course of 20 sittings, testified orally and in writing to the methods used to dispose of [some three thousand Armenian children]."

Although most guilty sentences were given in absentia, these trials acknowledged and created an official record of the Armenian Genocide. According to "The Ottoman State Special Military Tribunal for the Genocide of the Armenians" however, "these efforts were impeded by Allied incursions into Turkey, by a civil service that attempted to boycott the trials, and overall by an extremely fragile internal political situation." As a result, this acknowledgement soon turned to denial and those convicted became martyrs while the record of the trials "was actively buried by the new Turkish state." Allied authorities also arrested 150 men implicated in the genocide and sent them to Malta for trial, but ultimately they were all returned to Turkey without a trial.

Legacy of the Armenian Genocide

As of April 2021, only 30 countries recognize the Armenian Genocide. Meanwhile, Turkey continues to not only actively deny the genocide, but President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan claimed in 2020, "We will continue to fulfill the mission our grandfathers have carried out for centuries in the Caucasus." The New York Times writes that "even now, Turkish textbooks describe the Armenians as traitors, call the Armenian genocide a lie, and say that the Ottoman Turks took 'necessary measures' to counter Armenian separatism."

As Turkey's neo-colony, Azerbaijan's President Ilham Aliyev recently upheld this genocidal intent during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war and its aftermath. In 2021, a Spoils of War Museum was opened in Baku that featured an alley of helmets taken from Armenian soldiers who'd been killed during the war. Mannequins of Armenians are also included which, according to Radio Free Europe, were intended to be "the most freakish depictions" possible. Videos have even circulated of museum goers assaulting the mannequins.

On April 24nd, 2021, the United States recognized the Armenian Genocide after 106 years. Despite the importance of recognition, it can ring hollow when the United States fails to recognize its own genocidal history.