The Real Reason Spain Sold The Philippine Islands To The United States

Imperialism, oppression, revolution, war, even more war — it's kind of that narrative you get when looking at countries that have dealt with the fallout of European imperialism. That particular little progression, though, specifically has to do with the Philippines and where years of Spanish colonialism got them in the end. Which is to say, eventually becoming an independent nation in the mid-1940s (relatively recently, really).

But hundreds of years of history is a little bit too much for just this one read. After all, no one's here for a whole lecture on every one of those years — probably had more than enough of those in school. So here's just a little snippet of that whole history, about 50 years before the Philippines became its own nation. The era of Spanish influence was coming to an end, the age of American imperialism was starting. And, hey, Cuba is a part of that story, too.

Spanish imperialism and Filipino revolutionaries

Spanish influence in the Philippines stretches back a few centuries. When it comes to Spain entering the scene of Filipino history, the Association for Asian Studies explains that it started with Ferdinand Magellan, who landed in the Philippines in the 16th century and claimed an arbitrary area, encompassing a bunch of different islands and cultural groups, as a colony belonging to Spain. From there, Spanish rule was kind of rocky, the exact borders of the Philippines constantly changing with conquering and military defeats. It really just depended.

Somewhat fittingly, the Filipino response to Spain initially varied, generally from neutral to negative. Some groups acted fairly independently and didn't much care for the Spanish, while others were used as slave labor. But things eventually got worse, Spain trying to spread Catholicism to the Philippines, doing so by effectively erasing local histories and belief systems, punishing anyone who didn't conform to the new Christian ways. And that's not even getting into the full-on war Spain got into with the southern part of the Philippines.

Things were getting messy, and by the late 18th century, revolutionary ideas were beginning to spread, really taking hold in the latter half of the 19th century. There were vocal advocates for the Filipinos being recognized as free and equal to the Spanish. The idea only grew in popularity, and revolutionary tensions really came to a head around the 1890s.

The Spanish-American War

The end of the 19th century was really, really eventful for Spain, especially when it came to all of their colonies abroad. See, the Philippines were far from the only thing that Spain had on its mind. Cuba was the big one. Pretty much parallel to the Philippines, the Cubans were also fighting a long war for their independence and rebelling against Spanish rule, which was generally seen as oppressive and rather harsh (via US History). The difference, though, was where the US fell in that equation. Unlike in the Philippines, American eyes were on the situation in Cuba, watching as things escalated, tensions between the two countries brewing all the while (via History).

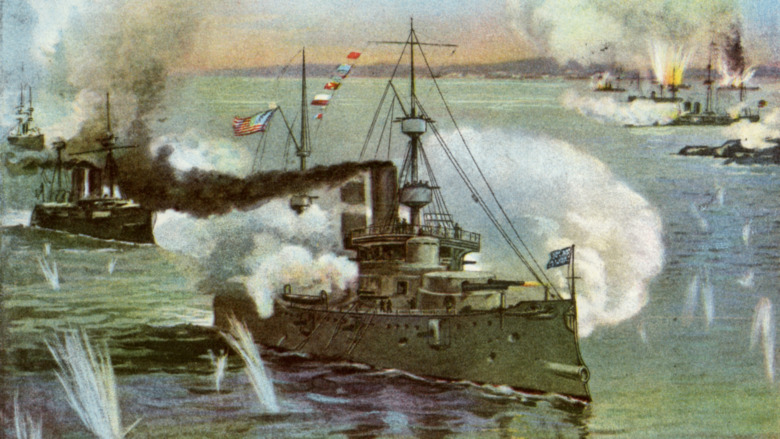

Then things boiled over in 1898 with the explosion of the battleship, the USS Maine. The newspapers caught wind of the tragedy and really ran with it, pointing fingers at the Spanish for being behind it (which was only speculation at the time, and has never been proven since). All of a sudden, the American public was clamoring for war and justice, and it didn't take long for the Spanish-American War to break out over the fate of Cuba.

Sure, this didn't directly involve the Philippines, but it did involve Spain and its colonies. It's basically the context for Filipino struggles at the very end of the 19th century, because all of that fighting bled over into the Pacific.

The Philippines weren't even supposed to be involved

The Spanish-American War had a lot to do with the situation in Cuba, but then, where do the Philippines factor into all of this? According to "Why did America Cross the Pacific? Reconstructing the U.S. Decision to Take the Philippines, 1898-1899," the American public had barely even noticed what was happening in the Philippines. Cuba was basically at America's doorstep, so it was hard to miss a revolution there; the same couldn't be said for the Philippines. It was just so far, no one really thought about it, and the idea of having a colony all the way across the Pacific just wasn't super feasible.

But, as The Diplomat says, the US Navy's Asiatic Squadron posed a problem. The US Navy had been making use of neutral ports in places like Hong Kong, docking there and also refilling on supplies, especially coal, which powered the ships. But when war with Spain broke out, then those ports wouldn't allow the US Navy to dock ships there. All of a sudden, the Navy was without any sort of base near Asia, sort of stranded and way too far from the mainland to really make things work.

So in the end, the idea of taking the Philippines came out of the Navy's plans as a way to guarantee that the US could have a port in Asia; it was just a convenient solution.

Filipino insurgents accepted American aid

By the time the Spanish-American War was in full swing, the Filipino fight for independence was also well underway, and with the two coinciding timewise, they ended up both affecting one another, too.

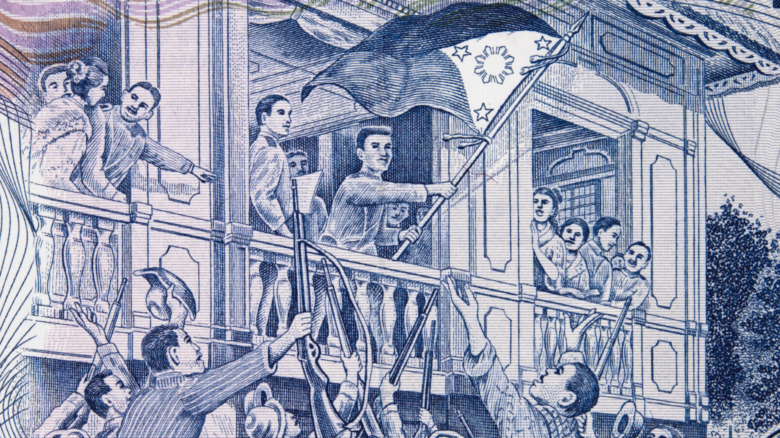

In the Philippines, revolutionary fervor had kicked up again in the late 19th century, especially in its final decade, according to History. An official revolutionary society had begun to form, planning for rebellion. Spain's discovery of that society prompted revolts to spread across the country, largely under the leadership of Emilio Aguinaldo. It didn't last long, though; the revolution was temporarily put down when Aguinaldo and his generals agreed to accept exile for the promise of reform in the Philippines.

The Spanish-American War changed that, though. With America taking an armed part in the conflict in the Pacific, it gave the insurgents another new opportunity. Aguinaldo ended up in talks with the US, ultimately agreeing to come out of exile and return to the Philippines. He and the US had become allies (at least, for the time being) as he began to lead attacks on the ground, liberating cities. As The Diplomat says, Aguinaldo and the insurgents welcomed the US fighting, essentially, on the same side. It allowed them to take control across the Philippines, loosening the Spanish hold on the region.

'The Battle of Manila'

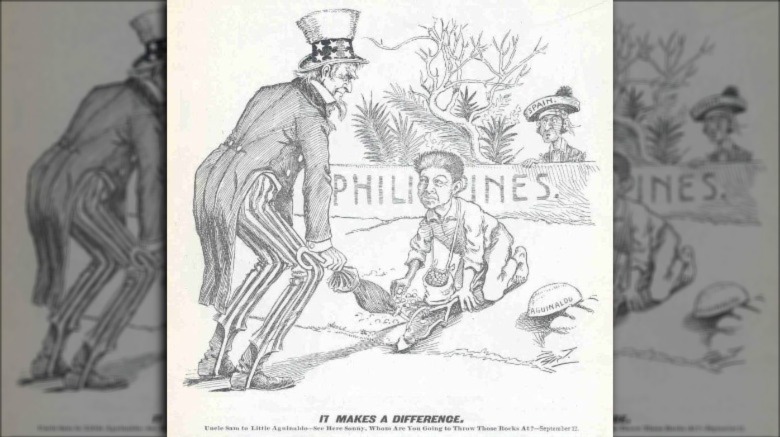

Alright, so maybe you're wondering why this is "The Battle of Manila," quotes and all. It's a military battle, right? So why the need for the quotes? Well, it wasn't really a battle. See, both Spanish and American views toward the Filipinos weren't actually all that great (via National Museum of American History). It was pretty close to the view of Native Americans at that time (so, again, not great). The US military largely viewed Aguinaldo as a nobody, while putting themselves in the role of saviors. Likewise, the Spanish wouldn't settle for surrendering to Filipinos; they would surrender to other white people, though.

And so, with the US Navy blockading the bay while Filipino insurgents besieged the Spanish-held city of Manila, a plan was concocted. The US Navy would shell a fort, and the Spanish wouldn't put up any resistance. Then, the US would transmit a code to the Spanish officers, telling them it was time to raise the white flag, at which time the US could then take the fort, and the city of Manila. On top of that, the Filipino rebels were to be kept out of Manila, while the whole thing looked like a legitimate battle (via History).

Basically, the Spanish were willing to give up Manila to the US, rather than appear to lose a battle to the Filipino insurgents and just grant them independence. It was all a way to save face.

The Treaty of Paris

The Spanish-American War all started near the end of April 1898 — the explosion of the USS Maine, the first battles, then the invasion of Cuba by the US in June of the same year, as summarized by ThoughtCo. By July (still in 1898), Spain was ready to start talking about peace, and the ceasefire was announced in August. Purely looking at the timeline, things were over and done pretty fast.

So once October rolled around, it was time for the peace negotiations in Paris. For the most part, it largely centered around Cuba and what would happen there. After all, a lot of the reasons surrounding the Spanish-American War circle around events in Cuba, and, long story short, Cuba was granted its independence.

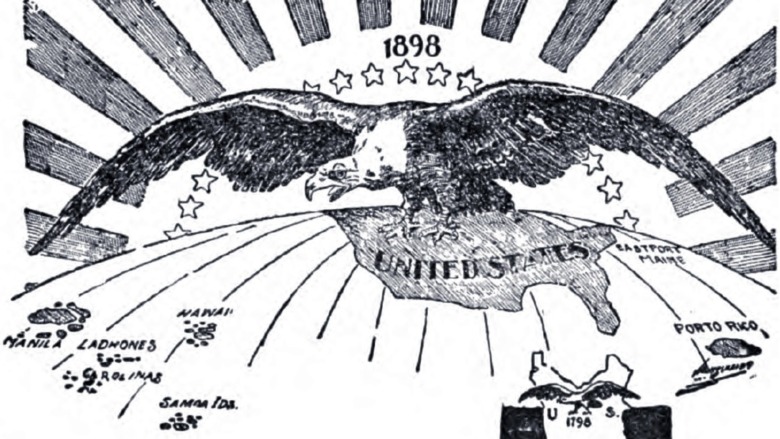

But then the war did have some other fallout. It'd left Cuba with a huge amount of debt — about $400 million. Spain ended up responsible for paying all of that back, and did so by giving Puerto Rico and Guam to the US. As for the Philippines, well, the US had occupied Manila just hours before the ceasefire was called. Even when Spain asked for only the capitol city, they were refused, ultimately selling it to the US for $20 million.

Spain was forced into selling the Philippines

Here's the funny thing about the way those Treaty of Paris negotiations went. As ThoughtCo says, Spain tried to negotiate to be able to hold onto just the capitol city of Manila, at the very least. The US shot down that idea, which was really just indicative of what the US mindset was going into those negotiations.

For a bunch of different reasons, President William McKinley was really concerned with what the image of the US could become in the aftermath of these peace talks. The US taking over the city of Manila ended up setting a precedent for them, all of a sudden (via Mt. Holyoke). They were a world power now, and the course of the war ended up creating new responsibilities as a part of that; what to do with the Philippines was part of those responsibilities, even if conquest hadn't been the original intention.

So in the documents written to the US representatives for the peace negotiations, there were some demands that they had to make sure were fulfilled. And when it came to the Philippines, the US wasn't leaving without control over Manila and its bay, and over the entirety of the island of Luzon (the largest island in the archipelago). So, no, that's not necessarily a complete cession of the Philippines, but the US negotiators weren't leaving without claiming a major stake there.

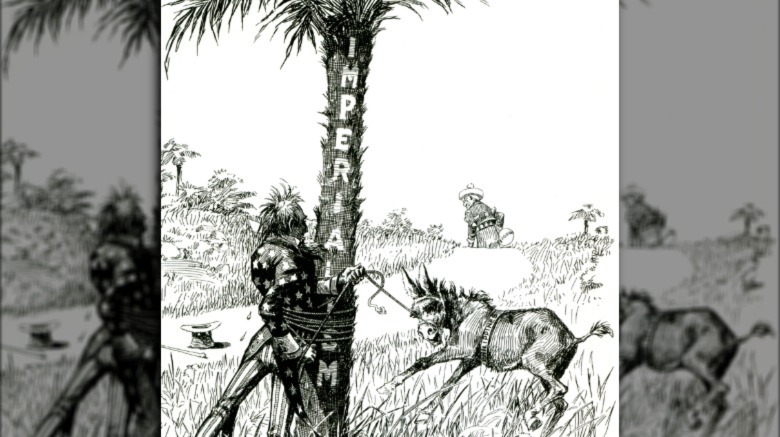

American imperialism and the Philippines

To put it bluntly, American imperialism was part of why this entire deal with the Philippines went the way that it did. It's just one of those things associated with the time period. One of the common narratives is that noted imperialists — including future President Theodore Roosevelt — just stepped on McKinley, wanting to join in an imperialist race against other (mostly European) nations who were busy trying to take lands for themselves in Africa and Asia. America hadn't done much comparatively, and some people thought it was time to catch up. On top of that, the Philippines in particular could open up potential trade routes and new markets for the US (via Mt. Holyoke).

That said, not everyone was actually a fan of expansion. Before imperialist ideology started growing, most people — including McKinley and people like Mark Twain (via National Museum of American History) — had been staunchly against expansion, thinking it was morally wrong. The Treaty of Paris was barely even ratified because of that debate (via ThoughtCo).

But even McKinley ended up kind of supporting the cession of the Philippines to the US. Known for his piety, he supposedly said that it was the job of the US to "educate ... and uplift and Christianize" the Philippines. Whether the quote is real isn't entirely certain, but it does fit that whole "White Man's Burden" thing from around the same time period.

Returning the Philippines would've looked bad

The Spanish-American War was fought largely on moral grounds. Really, the exact reasons for fighting are a bit more complicated, but to a large degree, the American public supported the war because they supported the Cuban insurgents, as The Diplomat explains. They saw a people fighting against an oppressive government which was putting revolutionaries into concentration camps and letting them die of disease or malnutrition, or else just executing them outright; it was all over the news (via US History). This was a fight for freedom.

And that just made the situation with the Philippines more complicated. As the war came to a close, more Americans were starting to learn about the situation in the Philippines, and all the descriptions are really familiar. The Philippines were chafing under Spanish rule — or, misrule, rather (via "Why Did America Cross the Pacific?"). Government and religious practices were regularly corrupt and intentionally oppressed the native people, who weren't allowed to advance. Much like in Cuba, Spain was seen as a clear enemy, while the revolutionaries were heroes.

So with that in mind, how could the US ever let Spain retake the Philippines, especially after the US Navy had secured Manila? Cuban insurgents get freedom, while Filipino insurgents — who were effectively fighting the same battle — get returned to their oppressors? That was hard to justify, so it was something of a weird situation.

An independent Philippines could've been in danger

In the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, Cuba got its independence, but a bunch of other places — the Philippines included — were sold or given to the US as territories. Why the difference in treatment? In the case of the Philippines, people started thinking that a Filipino government wouldn't really be able to stand on its own. According to "Why Did America Cross the Pacific?," people from the time thought that an independent Filipino government would quickly fall apart, each island declaring its own independence, or the entire nation just descending into civil war.

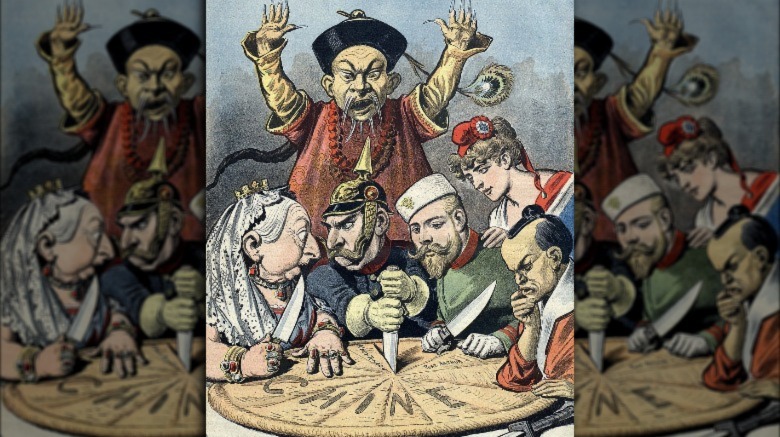

And this wasn't a time to let a nation fall apart. It could easily fall prey to the other nations trying to fulfill their imperialist dreams — The Diplomat names Germany and Japan in particular — especially at a time when there wasn't much land left for these countries to lay claim to.

To make matters worse, the state of international politics was precarious. Eastern Asia was kind of about to explode. China seemed about to potentially break apart, and a bunch of world powers — Britain, Germany, France, Russia, Japan — all had their eye turned to that part of the world. It was a place to power grab, should China actually fall to pieces, and the results of that could've been disastrous. The question over the future of the Philippines just made everything a little scarier.

The end of Spanish imperialism

Spain had been an imperialist nation for a long, long time. The Philippines, all up and down the Americas — Spanish influence is pretty widespread for a reason. But Spain's loss of its colonies in Cuba and the Philippines (basically the Treaty of Paris) ended up signaling the end of Spanish imperialism.

Here's the thing, though. According to ThoughtCo, the focus on imperialism and ambitions abroad allowed a bunch of problems to grow back home. The government was basically in shambles, constantly in flux and far from the picture of stability (via Encyclopedia.com). Calls for Catalan and Basque autonomy were rising, leading to further political instability. Labor unions clashed with business owners, causing social unrest. Things were a mess, plainly put.

But then, when Spain's imperialist goals came to an end, that became the perfect chance to finally turn an eye toward those internal problems. A new golden age of Spanish literature spawned out of a new generation of writers, calling for people to look to the past for an idea of what was truly Spanish, while also thinking forward toward the future. Those writers didn't themselves solve all of Spain's problems — especially the more tangible and less philosophical ones — but that period brought a bunch of new change. Agricultural, industrial, social — it was effectively a renaissance for the country. None of this was necessarily a reason that Spain gave up its colonies, but it was a really positive effect from it.

The problems weren't over, though

If you think about this entire sequence of events from the Filipino point of view, honestly, how much did it seem like things changed to them? ThoughtCo explains that, in a lot of ways, to them, nothing had changed at all. Sure, this was the US instead of Spain, but this was really just another step in their continued fight for independence.

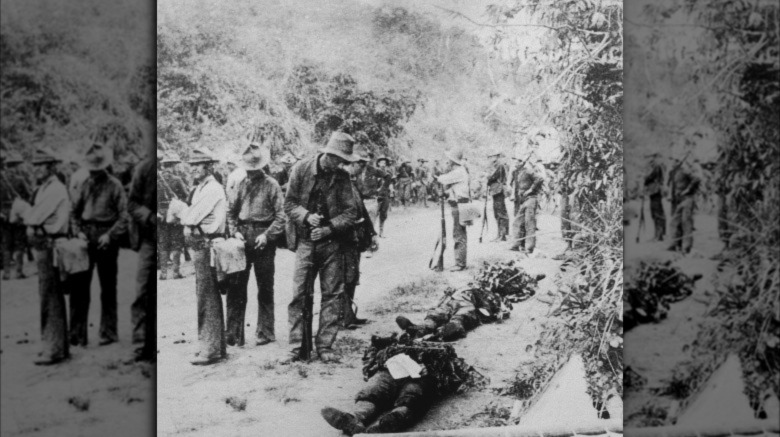

And so, with the Spanish-American War barely even over and the ink of the Treaty of Paris barely dried, in came the Philippine-American War. For another three years, Filipinos fought for the independence they championed, while the US found that winning the Philippines was a lot easier than governing it. Both sides eventually adopted guerilla style tactics and began resembling the Spanish that they'd kicked out: torture, terrorism, and the use of concentration camps. In the end, hundreds of thousands died — American soldiers, Filipino insurgents, and civilians — and hostilities officially ended in 1902, the US putting down the insurrection.

From there, History says that the US officially began administering the Philippines. Over the years, more power was slowly given to the Filipino government, putting them on a track to eventually become an independent nation. In 1935, they were established as the Commonwealth of the Philippines, then with the close of World War II, the US officially stepped away from the Republic of the Philippines in 1946.