The Most Powerful British Royal Consorts In History

On April 9, 2021, Prince Philip, the duke of Edinburgh, died a few months shy of his 100th birthday. Philip held the distinction of being the longest-serving royal consort in British history from 1921-2021. According to the Guinness Book of World Records, he held the position for 69 years and 62 days and was married to Queen Elizabeth II for more than 73 years.

As consort, he attended over 22,200 royal engagements, including charity meetings, openings, and travels with the queen. The loss of Prince Philip will undoubtedly have a significant impact on how the royal family moves forward. After all, a royal consort can exercise an incredible amount of power.

But what exactly is a royal consort? The term refers to the spouse of a ruling monarch. While the role comes with plenty of honors and duties, it lacks a constitutional role, according to the Associated Press. Nevertheless, the obscurity of the position hasn't stopped some queen and prince consorts from exercising a tremendous amount of influence and power.

Here are some of the most powerful British royal consorts in history.

The most influential queen consort in English history

Most historians agree that Caroline of Ansbach proved one of the most influential royal spouses in history. She enjoyed incredible sway as an advisor to her husband, King George II, and England's prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole. But her astonishing influence didn't stop there.

A descendant of the House of Hohenzollern, she lost her parents young, reverting to the guardianship of King Frederick I and Queen Sophia Charlotte of Prussia. During her time at the Prussian court, Caroline benefited from a liberal education. According to Lucy Worsley, author of "The Courtiers: Splendor and Intrigue in the Georgian Court at Kensington Palace," Caroline's intelligence and good looks made her a catch and "the most agreeable princess in Germany."

An avid lover of arts and history, Queen Caroline surrounded herself with distinguished thinkers, including the French philosophe, Voltaire. The witty writer declared her "born to encourage the arts and the well-being of mankind" (via the Royal Collection Trust). Because of her Prussian education, Queen Caroline supported freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and even advocated for compassion towards the rebellious Scottish Jacobite, says English Monarchs. The Regency Act of 1728 made her regent in place of her son, Frederick, prince of Wales, during George II's frequent absences.

The Dutch Protestant hero who seized the English throne

The Dutch nobleman, William of Orange, married his 15-year-old first cousin Mary II of England in 1677. Five years earlier, he rose to prominence as a Protestant hero who resisted the French occupation of the Netherlands, securing the position of Stadtholder of Holland. In June 1688, a group of Protestant English politicians known as the "Immortal Seven" approached William to overthrow his Catholic uncle, King James II of England. In November, William successfully landed in England, leading a multi-national army to overthrow Mary's father. Much of James II's army deserted for William's side, contributing to a bloodless victory, according to UK Parliament.

Known as the "Glorious Revolution," it secured William and Mary's roles as co-rulers of Britain. Although Mary II represented the heir presumptive to the English throne, William became more than her royal consort. She installed him as joint monarch, often deferring ruling matters to him. William of Orange proved an excellent military leader, deftly outmaneuvering his number one enemy, France's King Louis XIV, notes Undiscovered Scotland.

Mary II died suddenly from smallpox in 1694. Despite an early lack of affection, the couple had warmed to each other over the years. William proved inconsolable after her loss. He "swore that no better person had ever lived" (via History of Royal Women) and never remarried. He spent the remainder of his days as sole monarch. Military prowess, religious preference, and a unique marriage meant William of Orange ascended much higher than most royal consorts.

The Crusader Queen who inspired Courtly Love

Few medieval royals enjoyed the affluence and influence of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Her court at Poitiers during the 12th century proved instrumental in preserving the Arthurian legends and courtly love. But her powerful story started decades earlier with the death of her father, the duke of Aquitaine, and her inheritance of one-third of France. As the newly minted duchess of Aquitaine, she enjoyed a few hours as Europe's most in-demand bachelorette (via the History Channel). Then, the land-poor king of France arranged her marriage to his son, Louis VII. Following the king's death, Louis and Eleanor reigned as king and royal consort of France from 1137-1152.

During the Second Crusade, Eleanor proved uncharacteristically enthusiastic. According to Women in World History, she pledged thousands of vassals to the war effort and rode through the streets of Vézelay armored as an Amazon, urging residents to take up the cross. She even led 300 ladies in waiting to the Holy Land, inspiring ire from the church and a future ban on women participating in the crusades. Sporting armor and carrying lances, the female unit never fought, preferring work as nurses.

The Second Crusade failed, along with her marriage to Louis. Following an annulment, she fled to England to marry a man 11 years her junior, her third cousin King Henry of England. The marriage made her queen consort of England from 1154-1189. She later became the queen mother of three sons, including Richard the Lionheart.

The Celtic queen who challenged the Roman Empire

In 1697's "The Mourning Bride," the playwright William Congreve famously writes, "Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned" (via No Sweat Shakespeare). Had Congreve known Boadicea, who lived circa 30-60/61 A.D., he would have replaced the word "woman" with "mother." After all, few women better exemplify the Mama Grizzly in her fiercest form than this Celtic queen consort.

Married to King Prasutagus of the Iceni at the age of 18, Boadicea reigned as queen in northern Norfolk, says History. The couple had two teenage daughters but no male heir, which translated into Roman annexation after the king's death in 60 A.D. The annexation process included the seizure of the royal family's property and land. But Boadicea's enemies didn't stop there. Soldiers "publicly flogged the queen" and assaulted her daughters.

The Celtic queen swore vengeance on the Romans. The historian Tacitus recorded her threat, "Nothing is safe from Roman pride and arrogance. They will deface the sacred and will deflower our virgins. Win the battle or perish, that is what I, a woman, will do." True to her word, she led 230,000 troops against Rome, capturing forces, sacking Roman cities (including London), and displaying countless decapitated heads as chariot trophies. Tacitus claims that Boadicea's troops cut down both Roman and pro-Roman Britons, with reports ranging from 70,000 to 80,000 (via History and Historic UK). Unfortunately, Boadicea wasn't fully successful in driving the Romans from the British Isles.

The queen that converted a nation

Understanding an individual's historical influence can feel like piecing together a 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle. Such proves the case with Bertha of Kent, the daughter of King Charibert I of Paris. While a few dry lines from historical documents make up the gist of what is known about her, she proved powerful enough to receive direct correspondence from Pope Gregory I.

The pope expected Bertha, a devout Christian, to convert her Anglo-Saxon husband, King Aethelberht of Kent, and his kingdom. The couple had married sometime before 580, and the queen consort made enough progress that Aethelberht heartily welcomed Augustine of Canterbury in 597. He even permitted Augustine to set up a residence and preach the gospel.

In a letter to Bertha from 601, the pope provides fascinating glimpses into her life and how influential she may have been to Aethelberht. For example, he notes her education "instructed in letters," as well as her renown for "good deeds ... known not only among the Romans ... but also through various places" (via English Heritage). While contemporary historical accounts of Bertha's exploits prove rare, the pope saw her as a powerful ally. She also paved the way for Augustine's successful Christianization of the British Isles, although Augustine often gets all the credit, as noted by Historic UK.

Europe's first female ambassador and queen consort of England

Many people think of Catherine of Aragon as the jilted first wife of King Henry VIII. But she represented a powerful force in her own right, drawing on influential family ties and connections to bolster her position. The first female ambassador in European history (via Girl Museum), she advised Henry VIII on political matters. While Henry soldiered away in France, Catherine served as regent for six months in 1513. During this time, she handed the Scottish a crushing defeat at the Battle of Flodden. Besides a leadership role, she gave a rousing speech about English heroism spurring the troops onward to victory (via Smithsonian Magazine).

Henry VIII would eventually claim Catherine couldn't produce a male heir. But historical sources indicate she conceived at least six times during the first decade of their marriage. According to English History, she had two miscarriages and a stillborn daughter. Of the three live births (including two boys), only their daughter, Mary I, survived into adulthood, says The History Press. Mary, as the heir presumptive, represented a serious problem for England. No precedent yet existed for a female monarch, so Henry VIII appealed to the pope for an annulment. He hoped a new wife, namely Anne Boleyn, might bear him a boy.

Catherine persuasively argued against the annulment during the divorce proceedings. Ultimately, the pope ruled in her favor, forcing the king into a religious schism. Catherine retained the esteem of the English people, including her enemy Thomas Cromwell. He wrote of her, "But for her sex, she would have surpassed all the heroes of History" (as reported by the Tudor Times).

The rebel queen who dethroned her husband

The tale of Isabella of France is often portrayed inaccurately, like her depiction in 1995's Braveheart. Beyond her French origins and marriage to Edward II, king of England, little in the movie bears any relation to her real life.

She never met her father-in-law, Edward I (aka Longshanks), who passed away in 1307. And she had no extramarital relations with William Wallace, executed in 1305. Heck, she didn't even arrive in England until February 1308, according to History Extra. Despite modern depictions of her marriage to Edward II as unhappy, contemporary accounts paint a rosier picture. The couple had four kids and, by all accounts, were affectionate. At one point, he even rescued her from a burning building.

But everything changed in the 1320s when Hugh Despenser the Younger came onto the scene, currying Edward's favor and eroding Isabella's influence and position. In retaliation, the so-called "she-wolf of France" rallied an army and invaded England. There, she seized power and had Despenser drawn, quartered, disemboweled, beheaded, and chopped into bits (via the University of Reading).

Isabella forced her husband to abdicate the throne to their 14-year-old son, Edward III. What's more, she ruled as queen regent from 1327 to 1330 in her child's stead. What happened to Edward II (beyond imprisonment) remains a mystery although rumors of murder ran thick (via The History Vault).

Mary Queen of Scots' most influential counselor and ultimate downfall

Quantifying the influence James Hepburn, fourth earl of Bothwell, had over Mary Queen of Scots proves difficult. He represented the queen's only lifeboat on a treacherous sea of Scottish politics. As the rightful heir to the Stuart line, she grew up in France, returning to Scotland as a veritable foreigner. A staunch Catholic, she ruled an increasingly Protestant nation torn by the Reformation.

According to Undiscovered Scotland, she created a Privy Council of Scottish Protestants in 1561, including Bothwell. Then, in 1565, Bothwell helped her square off against her half-brother, squelching a rebellion. Although Bothwell and Mary had spouses, they appear to have grown increasingly attached. After her son's birth, the future King James VI in 1566, some historians assert the relationship developed into a full-fledged love affair, culminating in a crime of passion (via Mary Queen of Scots).

One thing's for sure. Nobody could deny Bothwell's growing power. Despite turning up as the number one suspect in the death of Mary's second husband, Lord Darnley, Bothwell received an acquittal, according to National Archives. But the trial-for-show barely assuaged suspicions about his (and Mary's) involvement in the murder. The elopement of Bothwell and Mary three months after Darnley's death represented a PR nightmare. The marriage rendered Bothwell royal consort, making Mary's disastrous reliance on his counsel official. But the relationship marked her downfall.

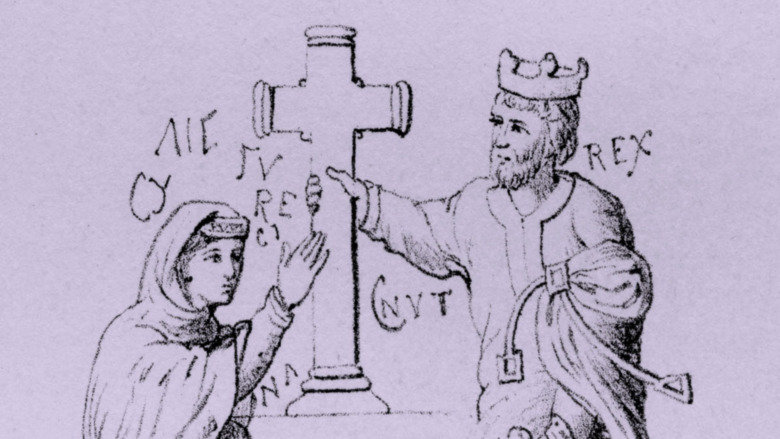

The double queen consort who tamed a Viking

According to Historic UK, Emma of Normandy married into a kingdom in crisis. Ruled by the Anglo-Saxon monarch Aethelred II (aka the "unready"), Viking attacks had plagued the land since the 980s and 990s. Despite encroaching Norsemen, the king and his consort had three children together, two sons and a daughter. What's more, Aethelred served a remarkable 38 years on the throne (via the British Library) before his death.

But by the first decade of the 11th century, Scandinavian attacks picked up in pace. Emma and the royal children fled into exile in Europe in 1013 during the invasion of Sweyn Forkbeard. After Sweyn's sudden death in 1014, his son, Cnut the Great, took control, eventually consolidating his rule over England by 1016.

How Cnut and Emma moved from enemies to lovers may never be known. But they married by 1017. The unlikely union blossomed into one of mutual respect and even affection, according to contemporary sources. As reported by ThoughtCo, documents after 1020 bear Emma's name, suggesting she took an active role as Cnut's queen consort. Two of Emma's sons would go on to become kings, Harthacnut of Denmark and later his older half-brother, Edward the Confessor, of England (via Historic UK).

Britain's first Black queen?

Clearly the better half to "mad" King George III, Queen Charlotte generally stayed out of political matters despite exercising considerable influence over her husband. After a wedding at St. James Palace, the happy couple settled into married life, producing 15 children. A remarkable 13 survived into adulthood, as reported by The Guardian. Her firstborn eventually ascended the throne as King George IV.

In 1762, the family moved to Buckingham Palace. Buckingham soon earned the nickname of the "Queen's House" as she birthed 14 of her 15 kids there. The royal couple loved fine music, keeping famed composer Johann Sebastian Bach's son, Johann Christian, on their payroll. They also received a visit from the musical prodigy, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, just 8 years old at the time.

Charlotte dabbled in amateur botany, eventually establishing the Kew Gardens, which still boast the most significant collection of flora in the world. Besides her fascination with botanicals, Charlotte also participated in charity work. She became the patron of the General Lying-In Hospital, renamed The Queen's Hospital in her honor. She also established a handful of orphanages to help meet community needs.

Recent scholarship suggests that Queen Charlotte descended from an African-Portuguese branch of the royal family. The line started with Alfonso III and a black Moorish concubine, as reported by the The Washington Post. What's more, some researchers point to marriage alliances with the Portuguese de Sousa family, further augmenting Charlotte's African ancestry, as reported by PBS.

The prince who used his position to help society

Prince Albert's and Queen Victoria's passionate marriage was the stuff of romance novels, according to Kensington Palace. During his lifetime, Albert exercised tremendous influence over the British Empire and his queen. On the humanitarian front, he pushed for reforms, including the abolition of child labor and slavery. He also worked to bring dueling between Army officers to an end (via History Answers), closing the door on a wasteful form of violence.

By the end of 1840, the Royal Family's website notes he acted as private secretary to the queen. He encouraged her to move away from the Whig party, taking a more apolitical approach to the monarchy than her predecessors. But his most significant areas of influence remained science, education, and the arts.

After his 1847 election as chancellor of Cambridge University, Albert devoted himself to improving the institution's curriculum. He founded the first London-based institution dedicated to scientific research, the Imperial College in London. Albert also adored music, sometimes selecting music for concerts by the Royal Philharmonic Society and the Academy of Ancient Music in London. Unfortunately, the prince's busy schedule led to overwork and health issues. After contracting typhoid fever in 1861, he passed away at the age of 42, and Victoria remained in mourning for the remainder of her life.

Everybody's favorite Queen Mother

During her lifetime, the Queen Mother, Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, ranked as one of the most popular royals. Devoted to the concept of the monarchy, she helped the royal family weather many storms. These crises included the abdication that put her husband, King George VI, on the throne. In the process, she became the first British-born queen consort since the House of Tudor, as reported by the History Channel UK.

Queen Elizabeth represented a source of strength for her husband throughout his reign. She assisted in transforming him from a shy, insecure, stammering man into a confident, well-spoken ruler.

She also endured the horrors of World War II with grace, including Buckingham Palace's bombing. Despite suggestions that she and the children should evacuate to North America, she refused. "The children won't go without me. I won't leave the King. And the King will never leave," according to the Royal Family website. In the years after the war, she remained a much-beloved presence with her impeccable fashion, sense of duty to the nation, and matriarchal guidance of the royal family during tough times.