The Real Reason The United States Acquired Florida From Spain

By the early 19th century, the United States of American was still a brand-new nation. Spain, by contrast, was a kingdom with quite a few centuries under its belt with an array of territories and other interests around the globe, particularly the territories of New Spain that were situated just to the south of the upstart new nation. Why, then, would such a seemingly powerful global force as Spain hand over a significant piece of its lands, the Florida territory, to the U.S. in 1819?

As it turns out, the story of Florida's history is a pretty complicated one. Ever since Spanish explorers first started trying to lay claim to it in the early 16th century, it had been the subject of seemingly endless fights over just who was supposed to be in charge of the peninsula. It was potentially strategic, with access to the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico, as well as the Caribbean to the south. Everyone, it seems, was willing to fight over it. So why did Spain give it up?

Yet, the actual land itself was rural, already inhabited by indigenous people who were suspicious of European settlers, and subject to intense heat and humidity. Why would the United States want it, anyway? Here is the real reason the United States acquired Florida from Spain.

Florida had been a contested territory for a long time

Practically since the moment Juan Ponce de León had claimed Florida for Spain in 1513, the lands in question were under dispute by just about everyone. According to Britannica, Leon returned to the area in 1521, having realized that Florida was not just another Caribbean island and, in fact, could be a valuable entry point for Spain into the rest of North America. He was supposed to set up a colony but was rather quickly wounded by local Calusa people and later died. Various attempts to establish that all-important settlement would follow, but none would be really successful for decades.

The major players over the course of Florida's contentious history included France, Spain, Britain, and eventually the newly-formed United States of America. Britain also raided the area occasionally, including one attack conducted by the notorious privateer Sir Francis Drake in 1586, according to The Florida Historical Quarterly. All of this often violent back and forth went on for centuries, even though many acknowledged that Florida was still mostly wild, already inhabited by indigenous people who weren't fans of the colonizers, and subject to hot temperatures and intense weather patterns.

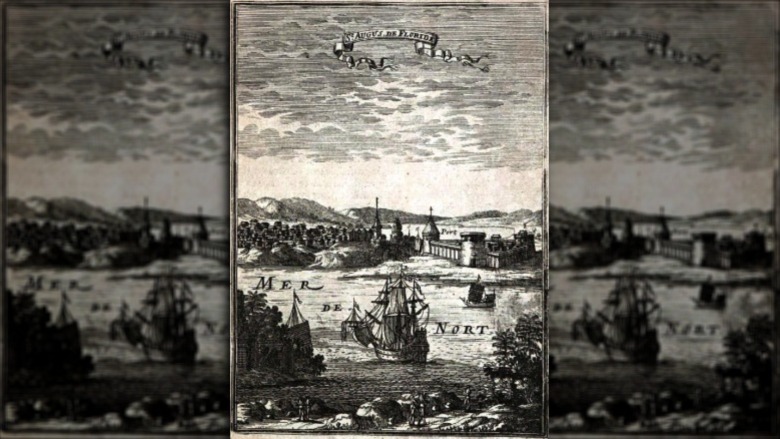

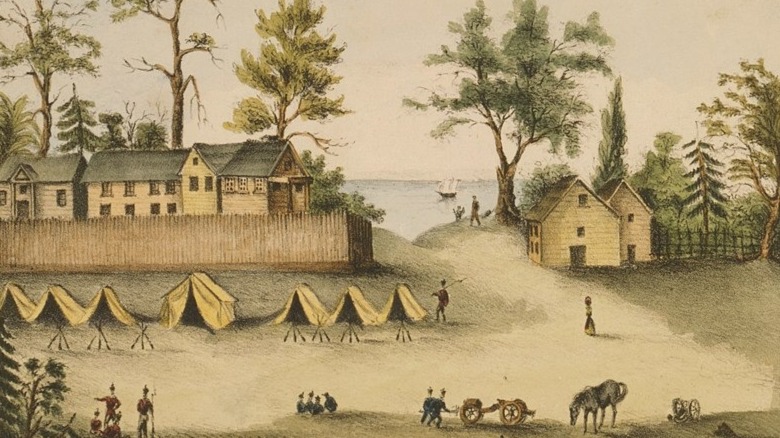

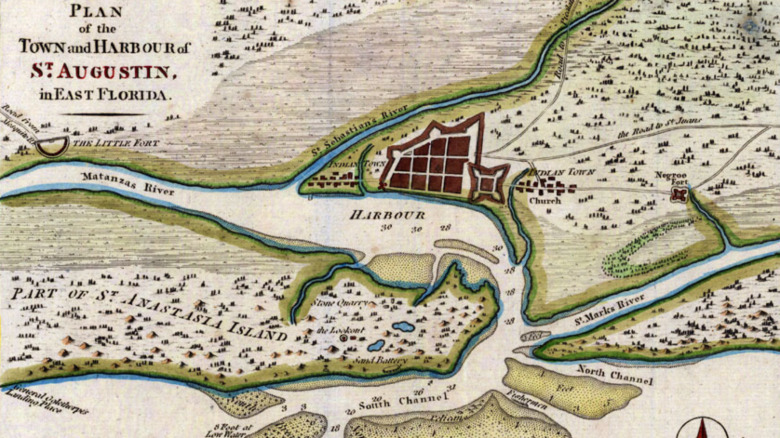

Florida was a Spanish colony by 1565

The First Spanish Period, as it's called, didn't begin until the establishment of St. Augustine on the Atlantic coast of Florida in 1565. According to JSTOR Daily, that's when Pedro Menéndez de Avilés finally succeeded where so many others before him failed — he got Europeans to settle in Florida. The group, which included an estimated 70 men, 100 women, and 150 children who were left in St. Augustine when everyone else sailed off, initially grappled with the harsh environment and isolation. However, the city persisted and has since become the oldest European-founded, continuously-settled city in the United States.

All of these colonial maneuvers came about because Spain was nervous about French explorers moving in on the region. As per History, Menéndez was sent along because pesky French Protestants were starting to settle there, who were even going so far as to establish Fort Caroline near modern-day Jacksonville on the Atlantic Coast. The majority-Catholic Spanish didn't like the religious competition, but also were leery of unfriendly settlers who might have an eye on their territory, not to mention the loaded Spanish treasure ships sailing nearby.

The British briefly took control of Florida

The next time Florida changed hands, it was due to a war, though the conflict in question was hundreds of miles away. Florida became a British territory because of the French and Indian War, also called the Seven Years' War. History says that the conflict was essentially a proxy war between Britain and France, fought out between the nations' North American colonists with both help and resistance from American Indian people throughout the region. Eventually, Spain would team up with France. Britain responded in part by seizing various French and Spanish territories elsewhere, including in the Philippines and Cuba.

To get these territories back, Spain had to do some maneuvering. As the National Park Service reports, the First Treaty of Paris that ended the war in 1763 gave Florida to Britain in exchange for these more lucrative lands. As a result, most Spanish colonists in Florida left for Cuba.

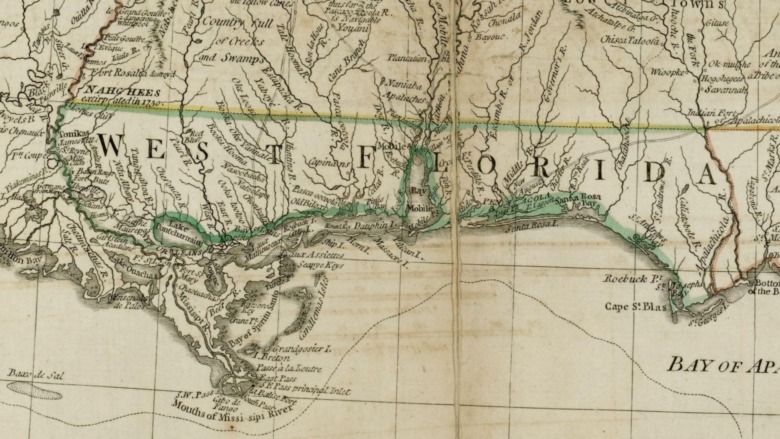

The new governors of the territory set about dividing it into East and West Florida, which included parts of what is now Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, per Exploring Florida. During the American Revolution, Florida even became something of a haven for Loyalists who wanted nothing to do with the war. In 1783, the Peace of Paris agreement gave Florida back to Spain, in part because Britain had lost the American Revolution.

The territory of Florida proved troublesome for Spain

In 1784, when Spain had fully regained Florida — though it had already secured West Florida a few years earlier, as Exploring Florida notes — it may have felt like a victory. Yet, as the years wore on, the Florida colonies proved to be more and more like a millstone around the kingdom's neck.

Initially, colonists were reluctant to settle there, though the Spanish governor had promised to treat everyone fairly, according to the National Park Service. Officials attempted to attract new settlers through a series of benefits, but it took a couple of significant concessions to actually get people to move into Florida. The first, enacted by 1786, was to allow Protestants to live in the ostensibly Catholic territory. The second was the government's sanction of slavery in the territory, which made way for a series of plantations and slaveowners in Florida.

It didn't stop with diplomatic and moral concessions, however. Constituting America notes that endless boundary debates with the newly-formed United States made the territory more effort than Spain might have thought it was worth. Money problems for the kingdom didn't help, either.

It was difficult to persuade settlers to live in Florida

Living in Florida was a tough proposition for European settlers. Few, if any, were excited about the climate, conflicts with Native people, and the endless changing of governments that left settlers' futures and fortunes in limbo.

The National Park Service reports that, in the Second Spanish Period lasting from 1784 until 1821, Spanish officials attempted to sweeten the deal through a variety of methods. Governor Vicente Manuel de Céspedes gave out large parcels of land, serious tax breaks, and even offered to pay people outright for starting a homestead in Florida. Still, growth was slow, a pretty alarming prospect for a struggling colony that simply needed more people to survive.

Florida wasn't a wasteland, however. Yes, it can get oppressively hot and humid, but the year-round warm weather and abundant natural resources could be attractive, especially to settlers who had dealt with harsh winters elsewhere. The Orlando Sentinel notes that European settlers often had to adjust their expectations of what would grow in the climate and what was good to eat, shifting their diets to include prickly pear, acorns, and a local plant known as the "coontie fern."

Florida was a land of runaways

As in so many other places, the original inhabitants of Florida were in for some serious trouble once explorers and colonists began to show up in their territory. By the mid-1700s, many of the indigenous people of Florida had been devastated by disease and conflict with settlers, Britannica reports.

Eventually, Muskogee and Creek people from around Georgia, began to migrate south in the Florida territory, according to the Florida Department of State. It took until the 1770s for this group of indigenous people from a variety of tribes to become collectively known as the Seminole, which roughly translates to "runaway" in reference to their origins.

The Seminole, however, did not consist entirely of Native people searching for new places to settle. Beginning in the early 1700s, they were joined by increasing numbers of runaway slaves who came to be known as "Black Seminoles," Britannica says. Florida was especially attractive to Black people fleeing enslavement, as Spain had abolished slavery there in 1693. For people living in the southern British colonies, such as Georgia, it could be a relatively short trip over the border to freedom. Eventually, it became clear that the U.S. wanted to claim Florida in part to appease Georgia landowners who wanted to cut off this escape route.

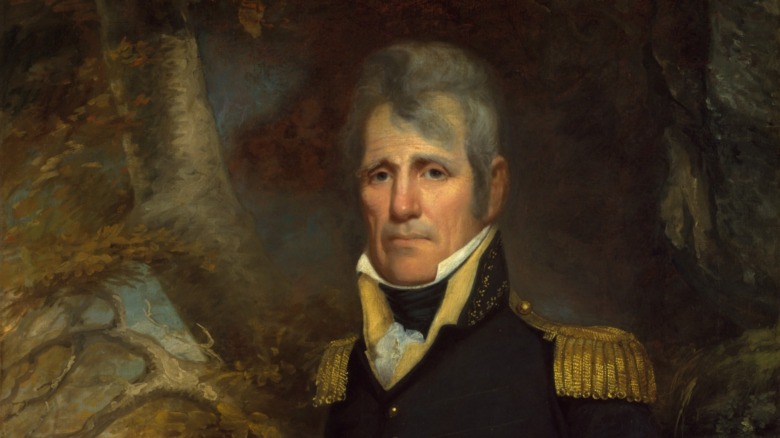

Andrew Jackson had connections to early Florida

Depending on who you ask, General Andrew Jackson was either a big help or a huge hindrance regarding American relations with Spain, especially when it came to the thorny problem of the Florida territory and runaway slaves. According to Constituting America, by 1818, Jackson was stationed at the border between the U.S. state of Georgia and Spanish Florida. He was ostensibly there to secure the oftentimes disputed boundary and also to stop runaway American slaves.

However, the future president of the United States wasn't going to let something like a silly international border get in the way of making trouble. Jackson used the excuse of pursuing slaves in order to boldly enter the Spanish territory, capture a couple of the other nation's forts, and even execute two British people for allegedly helping hostile Natives.

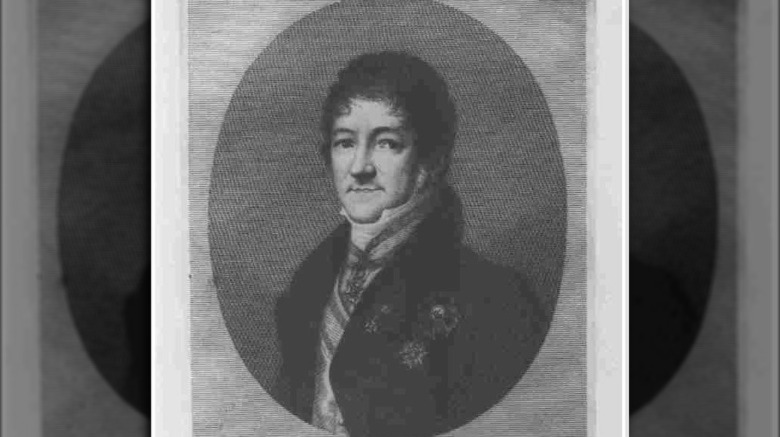

This violent escapade precipitated a miniature diplomatic crisis, with President James Monroe ultimately supporting Jackson and Spanish official Luis de Onís backing off, lest the U.S. take further action and officially seize Florida.

An American-led rebellion made Spain's job more difficult

The acquisition of Florida by the United States began in secret. The Jacksonville Historical Society reports that, in early 1811, Congress secretly agreed that the nation should take over Florida, going so far as to pass an act to formalize their intention. This eventually morphed into the idea that the U.S. should support local uprising against the Spanish government, though this idea raised alarm bells for some members of the government, who claimed that this was all an excuse to move American troops into foreign territory.

This is more or less exactly what happened. A group of Americans living in Florida, colloquially known as "Patriots," were emboldened by the U.S. government's overtures, though the War of 1812 soon distracted Washington from the Floridian cause, according to The Daily Commercial. They went ahead anyway, claiming territory in east Florida, reportedly with the help of the U.S.

However, the plan crumbled quickly, with President James Madison publicly condemning the rebels. When the Seminoles teamed up with the Spanish against the American rebels, it was all over. Though it was unsuccessful, this incident may have further convinced Spain that it was time to get rid of Florida once and for all.

Seminole people weren't happy with other countries getting involved

For the Native people living in Florida, the matter of who took control of their territory and how they managed it was serious business. Serious enough, that is, to start multiple wars over the whole thing.

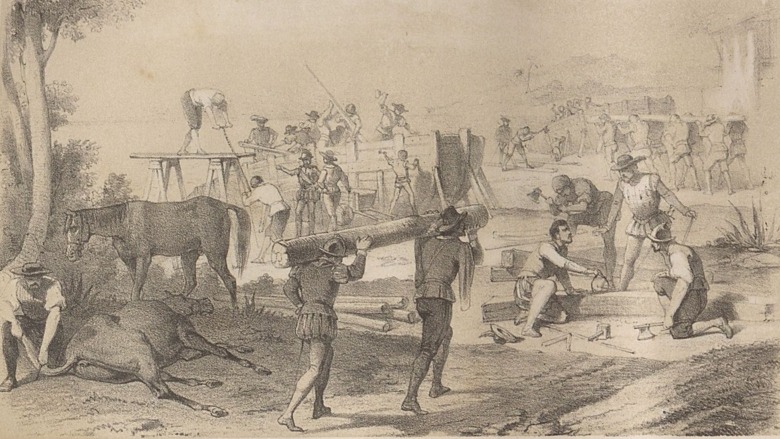

The First Seminole War (1817-1818) began when Andrew Jackson attempted to recapture runaway slaves living amongst the Seminole, according to the Seminole Nation Museum. The action was also taken in retaliation for earlier Seminole attacks on American settlers, which had been egged on by none other than the Spanish territorial government. Jackson's forces entered the territory and attacked Seminole outposts, pushing the tribe further south into the peninsula. The events of this war pushed Spain to finally hand over Florida to the United States.

It was followed by a Second Seminole War (1835-1842) and a Third Seminole War (1855-1858), both of which generally focused on land disputes between the U.S. and the tribe, as well as the more-or-less forced migration of tribal members from Florida and into reservations in Oklahoma's Indian Territory. Per Legends of America, some were at least allowed to remain on an unsanctioned reservation in southern Florida, while others continued to live for a time in the depths of the least developed areas, like the Everglades swamp.

U.S. relations with Spain were already pretty tense by 1819

There has likely never been a time when international politics wasn't a complicated beast. It was certainly so in the early 19th century, when the tenuous relationship between the United States and Spain was about to play a fateful role in Florida's future. As Constituting America notes, previous treaties had attempted to more properly define the border between Spanish and U.S. territory, but with scattershot results. Americans also argued that Spain owed them, both for Spain helping seize American merchant ships trying to trade with Britain, and for blocking American merchants from doing business in New Orleans, a violation of an earlier treaty.

Eventually, Napoleon got involved, though not directly. In 1808, France invaded Spain and Napoleon set up a puppet government headed by his own brother. A resistance movement arose and the United States, wanting to side with the resistance and against Napoleon, also had to break with Spain.

This got pretty awkward for Luis de Onís, the Spanish minister of government who was stuck trying to negotiate with U.S. officials in Philadelphia. President Madison gave him the cold shoulder, though Onís was at least able to meet with Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, according to Adams' memoirs. Still, Onís was kept in political purgatory for years and Spain struggled with war and diplomatic disputes both in Europe and North America.

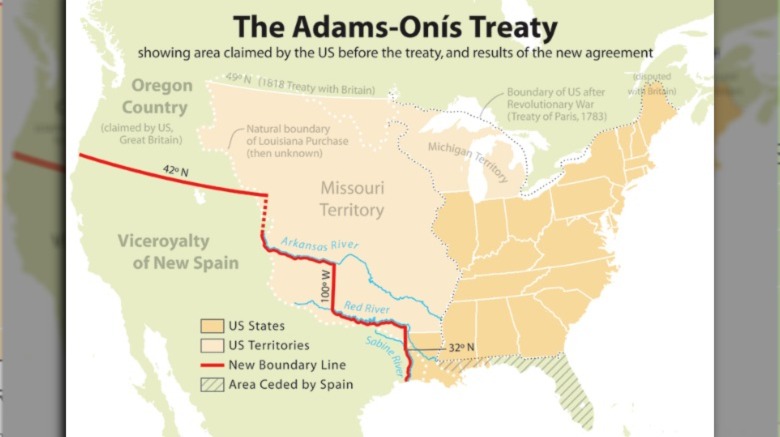

The treaty for Florida was signed on February 22, 1819

The near-constant stream of diplomatic snubs, international conflicts, and general misunderstandings between the United States and Spain finally came to a head in a peaceful sign-off on February 22, 1819. That's when, according to Constituting America, U.S. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams signed the Adams-Onís treaty with Spanish official Luis de Onís. Since then, the agreement signed by the two has gone by a variety of other names, including the long-winded Treaty of Amity, Settlement, and Limits Between the United States of American and His Catholic Majesty. Fans of brevity also called it the Transcontinental Treaty.

And it was truly transcontinental, in that the treaty helped clear up some frustratingly vague parts of the earlier Louisiana Purchase and further solidified U.S. territory as far as the Pacific Northwest. It also ostensibly cleared up any lingering sense on the American side that the nation was owed financial compensation for Spain's actions during previous conflicts, surely a relief to the cash-strapped kingdom.

The borders established by the treaty went far beyond Florida

Adams insisted that the boundaries of the treaty should extend to the Pacific Ocean. This broad and rather bold move opened up a clear path for the United States to become a serious player in the nation game, thanks to its future possession of valuable land on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. So, according to the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, the treaty not only concerned Florida, but established a firm border between New Spain to the south and the United States to the north.

In return, the Transcontinental Treaty stated that the United States would release all of its previous complaints against Spain, including the charges that French privateers working with the kingdom had seized American vessels and goods. The document even granted Spanish vessels the right to dock in the newly American cities of Pensacola and St. Augustine without increased duties or taxes, presumably to show no hard feelings after this huge new land acquisition.

Florida didn't become a state until 1845

After all of the colonizing, wars, skirmishes, political awkwardness, and seemingly endless diplomatic exchanges, Florida was finally part of the United States. Yet, though the treaty was signed in February 1819, no one would get around to making Florida a state for over 20 years.

Per the Florida Department of State, the territory wouldn't officially become a U.S. state until March 3, 1845. What gives?

It appears to have been granted statehood in part because most of the prospective voting residents supported slavery. As The Florida Historical Quarterly reports, by the time the territory was granted statehood, the issue of slavery was becoming an increasingly contentious one throughout the nation. Even within Florida, there were heated debates over not just the issue of whether or not Florida would become a slave state, but how residents would be hit by taxes and the effects of an 1837 financial crisis on the territory's economy.