The Double Life Of The Children's Author Who Spied For The British

Picture this — a British spy, elegantly but sharply dressed in a tuxedo, martini held in one hand as his eye moves smoothly through the upscale restaurant. From across the room, he spies his target — a rich and powerful bureaucrat who's surrounded by secrets. He waits, taking the occasional sip from his drink, until his target seems to have had his fill of the night's pleasures, taking his coat and heading out into the night. The agent rises after him and follows into the crisp air, tailing a safe distance behind, always sticking to the shadows.

You know, classic spy movie stuff. But now imagine a lush, green countryside, tucked away in the quietest corners of England. Rolling green hills dotted with delicate flowers of all colors. A still lake, glittering in the warm sunlight. Nearby stands a modest but very comfortable home, where a middle-aged man sits at a desk near the window. Taking inspiration from the beauty in front of him, the author picks up his pen and sets it to paper.

These are honestly two very different lives. Completely different vibes, right? There's no way these two little scenes could be at all connected. They feel like they come from entirely separate worlds.

Funnily enough, though, that's not even kind of true. Because this is sort of a representation of the life of Arthur Ransome, MI6 spy turned children's book author.

Arthur Ransome is most well known as an author

The name Arthur Ransome is probably most heavily and easily associated with the literary world. According to the BBC, his early attempts at breaking into the world of writing were met with failure after failure, though he eventually did find success writing articles for magazines. The things that really put him on the map, though, were his works as a literary critic — essays and books on other famous authors, like Edgar Allan Poe and Oscar Wilde. The latter ended up dropping him into a legal battle with Lord Alfred Douglas. Ransome won the case, but by all means, it seemed to be a tough time for him.

His bigger hit came later in life, though — the Swallows and Amazons series, much loved by kids over in the United Kingdom. The Guardian gives a short review of the series, describing it as charming. Which is a really simple way of putting it, and perfectly so. These aren't crazy adventures or epic tales filled with action. They're literally just stories of kids being kids. Taking a journey to the nearby lake and playing around outside, getting really invested in games of make-believe. In a lot of ways, they just feel familiar, like the old days where you would pretend to be pirates or adventurers or superheroes (but taking place in the idyllic English countryside).

The simple morals of Arthur Ransome's children's books

Born in the 1880s, Arthur Ransome's morals and views on life really were a product of their time. In general, The Guardian makes it sound like he held to these old-school, traditional, and posh English vibes, despite the heavy industrialization that was happening all around him. You know — big old smokestacks, soot in the air, abuse of the working class, all that industrial-era stuff.

Ransome's life generally didn't look like that, though. His professor father held the view of equality for all (despite looking down on his servants), and Ransome would spend time out in the idyllic countryside with his friends who despised industrial, urban life. Bohemian is another way the article puts it, which is fairly accurate.

That very much carries into his children's books. They feature settings and characters and ideas that fit that idyllic Bohemian aesthetic, while circling around very simple and straightforward morals. According to Publisher's Weekly, that "moral simplicity" is what people tend to like about his novels. The funny thing, though, is that Ransome's actual life (and the world around him) was far, far more complicated than anything that he seemed to portray in his novels. Honestly, it turns out that the dichotomy is pretty surprising.

Arthur Ransome's adventures in Russia

By 1913, Arthur Ransome found himself in need of escape. Between a failing and unhappy marriage and a lawsuit filed by representatives of Oscar Wilde for libel, he just really wasn't having the best of times (via The Guardian). And so, he just left England, heading to Russia with the intent of researching Russian folk tales and a contract to write a guidebook to St. Petersburg, as per the BBC.

As it would turn out, 1913 was quite the year to go to Russia, of all places. The 1910s were a turbulent time (between World War I and the Russian Revolution), and all of a sudden, Ransome found himself right in the middle of it all. Given the situation, his path and plans changed, and within a couple years, he began working as a journalist for the Daily News and Manchester Guardian, as The Ruskin Museum explains, reporting on the, frankly, wild situation he had ended up in.

But, on top of being suddenly thrown from the frying pan into the fire, Ransome was sort of in a unique situation from the start. He was already one of very few English journalists still in Russia by the start of the revolution, but he'd also spent multiple months in 1913 learning Russian fluently. So that made him a rarity — an English journalist who could understand everything happening without the need for a translator. He could report on exactly what was said.

The Russian Revolution

To really get into why this Bohemian-lifestyle-loving author was living a double life, it's nice to know the world Arthur Ransome lived in. And while most people are probably pretty familiar with what would happen later — Communism and the Cold War — here's a little primer on the earlier part of it.

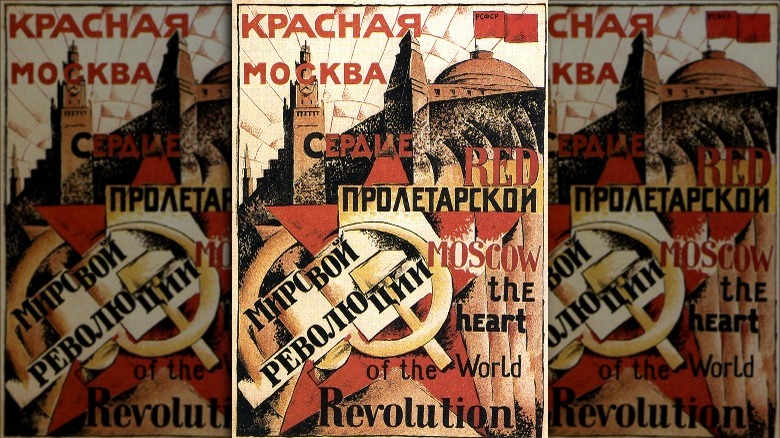

According to History, Russia was in a pretty bad place at the turn of the 20th century. The country had a huge (and growing) lower class that was growing more and more frustrated at the terrible standard of living. The czar promised changes after 1905, but World War I just made things worse, crippling the economy. Two revolutions in 1917 were meant to fix that. The February Revolution deposed the czar and enacted some measure of social reforms, but the new provisional government couldn't solve more pressing issues (like food shortages). Further frustration led to the Bolshevik Revolution in November, which called for the fall of the bourgeois-led provisional government in favor of a government led by councils of everyday people. Other conflicts cropped up shortly after, but more or less, that's the start of communism on a large scale.

Western countries were concerned. The British Library points out that one of those concerns centered around the idea of Russia pulling out from the war. But public opinion also spoke to some level of fear over things like similar revolutions happening at home and the spread of communism in general, so Western governments were very anti-Bolshevik.

Arthur Ransome was close with the Bolsheviks

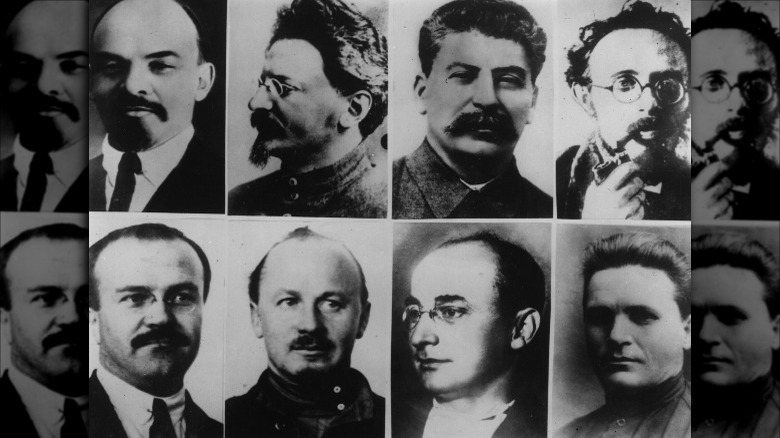

Despite the wider Western view of the Russian Revolution and the Bolsheviks leading it, Arthur Ransome was, again, a pretty unique case when it came to his views. Where a lot of Western writings tended to do a lot of vilifying, Ransome was actually pretty close with quite a few of the Bolsheviks. And not just low-level members of the party, but a lot of the Bolshevik leaders, too.

According to The Guardian, he was on friendly enough terms to secure interviews with just about all of the Russian leaders at the time, including Leon Trotsky. As the World Socialist Web Site suggests, he was the only reporter that the group of revolutionaries believed would actually be honest about what was going on around him. And, apparently, that opinion wasn't just held by random people in the party. Even Lenin himself had a really high opinion of Ransome and his work.

But this went even beyond just professional respect. Ransome eventually became close friends with Karl Radek, Trotsky's number two and Bolshevik propagandist. By 1918, he was living with Radek and his family, and Radek himself would actively help Ransome with his work, supplying him with papers to leave the country and writing the preface to one of his books. Maybe even bigger than that friendship, though, was Ransome's relationship with Evgenia Shelepina, Trotsky's private secretary in 1917 and, later, Ransome's second wife.

A Bolshevik sympathizer?

Arthur Ransome was never really all that secretive about what his opinions were of the Bolsheviks and the ideals that they rallied behind. Honestly, it's almost surprising he was so honest about it, especially given the Western lens that the Russian Revolution is usually viewed through in the decades since, because Ransome was really heavily supportive of all of it.

As The Guardian says, he believed in both the February and October revolutions — a fight against the monarchy in favor of democracy and a chance for the morally correct side to succeed and make things better. His view of the Bolshevik leaders were much the same. To him, they were really intelligent in how they brought this revolution about, argues World Socialist Web Site, but also hard working heroes who championed the people and fought endlessly for the rights of all, not just for the bourgeois upper class.

He might've even supported them to such an extent that he approved of the Bolshevik-created Cheka (secret police) and their use of extreme measures like censorship and executions without trials, just to put down counter revolutionaries.

With that in mind, England was (understandably) worried that Ransome was a Bolshevik sympathizer and revolutionary himself. When he returned home in 1919, he was actually arrested under the Defense of the Realm Act (via BBC). He was eventually released after convincing the authorities that he wasn't a communist, but suspicions still surrounded his name for years, notes Spy Culture.

An MI6 spy?

So, here's the part of the story that gets pretty bizarre. Yeah, Arthur Ransome went to Russia and ended up embroiled in all the drama surrounding the Bolshevik Revolution and befriended a few of said Bolsheviks, but it turns out that's not even the weird part.

According to The Guardian, on what seemed like a pretty unremarkable trip to Stockholm, Ransome was suddenly approached by agents from MI6. They wanted to recruit him as a spy for the British, their insider within the Soviet upper management. His position and connections made him perfect for the job, and they successfully did get him on board. He even had an official code name — S76.

That said, the road ahead was somewhat rocky. According to Spy Culture, MI6 themselves admitted to mishandling his situation, often skeptical of where his loyalties lay because of his friendship with the Bolshevik leaders.

Nonetheless, British intelligence officers did admit that he was a considerable asset to them. They ultimately recognized that he was loyal to MI6 and had passed a decent amount of information off to them.

A double agent?

Knowing that Arthur Ransome was fairly sympathetic to and supportive of the Bolshevik cause, as suggested by World Socialist Web Site, while still acting as an agent of MI6, it's easy to wonder what exactly he was doing and where his true feelings lay. The same sentiment was around during his lifetime, too.

There's been some speculation that, while serving MI6, Ransome was actually working as a double agent for the Bolsheviks. And, honestly, there's some reason to think that's true. The BBC says that at various points, he helped his wife smuggle millions of roubles worth of diamonds and pearls out of the Soviet Union (as well as some money into Sweden, according to The Guardian). The exact circumstances are a little hazy, but there's the possibility that wealth was used to push communist propaganda throughout the rest of Europe. But at the same time, while Ransome was involved, those speculations fall more on his wife and her intentions. Similarly, there are questions about whether or not he did pass any information to the Russians while he was especially close with them, but it doesn't seem like he was ever given any particularly sensitive information that would've been worth passing on anyway.

Really, it's more likely he was just a convenient person for both sides to use in order to further their own interests. The British could use him for information, and the Russians trusted him to tell the world what was going on. It might've been as simple as that.

Just an honest journalist?

A lot of the speculation about Arthur Ransome and his questionable loyalties all tends to circle around the two sides of this story — the British MI6 and the Bolsheviks. But Ransome himself had opinions about what he was trying to do, too, outside of all that.

At the end of the day, Ransome really just seemed to want to be the most honest journalist he could be. According to The Guardian, he just wanted to make the situation in Russia more widely known. He wanted to make sure all sides of the argument were making it out there, so that, in the process, maybe these two governments could eventually see eye to eye (via Publisher's Weekly). For him, this determination to be truthful and transparent about everything he saw was the most noble and patriotic thing he could do.

But it wasn't all quite so positive. Yes, he wanted to do it for his country and to bring about more peaceful relations, but he fought back against the lies and censorship that he saw in the British media. World Socialist Web Site claims Ransome knew he had a platform that people would listen to, and he wanted to warn the British people away from what he saw as "intellectual sloth." People were just blindly taking in whatever the government said, when, really, they should've been going to figure out what they thought for themselves.

Maybe Arthur Ransome misread the situation

Arthur Ransome was definitely a really staunch supporter of the Bolshevik cause, and that probably did stem pretty largely from his view that the entire revolution was being fought for valiantly moral causes. But there's definitely arguments out there that his faith in the Bolsheviks was potentially a bit naive and misplaced.

Author Roland Chambers raises the point that Ransome might've just been blind to any of the potential bad that the Bolsheviks were sowing in Russia, as noted by World Socialist Web Site. After befriending people like Karl Radek, he was suddenly being treated almost like nobility. No more of these dark, cheap hotel rooms. Instead, he lived in relative luxury with his new friends. He basically just saw what the Bolsheviks wanted him to see — look, they could offer him this comfortable lifestyle, so just imagine what else they could do for the country! But, in reality, he was only being shown a really small part of the story.

Publisher's Weekly also quotes David R. Godine, who points out that Ransome might have operated under the false assumption that the Bolshevik government would eventually turn into a democratic one (which it didn't). He might've shown his support because his perceived end goals were way different than the reality. It's easier to champion founders of democracies than new dictators, after all.

Or maybe, like The Guardian says, he just chose not to see the problems, continuing to approve of the Bolsheviks, even when they began suppressing democracy entirely. It's hard to say.

Where Arthur Ransome's political and literary lives meet

On the surface, it looks like Arthur Ransome's two lives — MI6 spy and children's book author — are completely separate. Even when you look at the rest of his life post-spy work, it really does just seem like he lived two entirely different lives. His novels are all idyllic and picturesque, and according to The Guardian, upon moving back to England, he seemed to leave it all behind, never directly referencing his spy work, even in his own autobiography.

But Roland Chambers brings up some interesting points, summarized by Publisher's Weekly. Essentially, the Swallows and Amazons books are really more nuanced than they seem on the surface. The characters are all young, but even still, they're "constantly fighting, drafting secret treaties, and making peace." That sounds sort of familiar, doesn't it? It pretty much describes the real world that Ransome was living in — World War I, the Russian Revolution, and spying for MI6. It's all there in his novels, just appropriately softened for kids to read. It makes for this interesting contradiction of real-world political problems and idyllic fantasies, and Ransome was able to pull all of that together into one cohesive work.

A quote from David R. Godine in the same article seems to sum it up — "His literary life might not have happened if he hadn't had his political life." Those two lives of Ransome's look mutually exclusive, but really, they might be more interconnected than they initially seemed.