Things The Mummy Gets Right About History

Few of us really expect a Hollywood movie to be historically accurate. Audiences watch for the stories and characters and don't necessarily care whether a person is wearing exactly the right clothes for the time period or speaking the correct version of an archaic language. Unless you're a professor in a very particular field, chances are good that you won't even notice any historical flubs.

And who would expect 1999's "The Mummy" to be accurate in any way? It's an action adventure film that's clearly based more on its Hollywood predecessors than an Egyptology tome. After all, the big bad villain is a supernaturally resurrected mummy who can bring on the 10 biblical plagues at will. Surely there's no reality here.

However, among the thrilling storylines and computer generated effects, there are real grains of truth in "The Mummy." In fact, there may be a few things that you assumed were nonsense but that, upon closer examination, give us real insight into the lives of ancient Egyptians. Let's give credit where it's due. These are the things that "The Mummy" actually gets right about history.

Imhotep was a real ancient Egyptian

The villain at the center of "The Mummy" certainly seems fake. After all, he is a half-mummified shambling corpse for most of the film, and a pretty devious guy overall. That pretty firmly places Imhotep in the world of Hollywood fantasy, right? Except, there really was a famous ancient Egyptian named Imhotep.

The real Imhotep hails from the time of the pharaoh Djoser, according to the American Research Center in Egypt. Djoser sat on the throne during the Third Dynasty in the Old Kingdom, which took place from 2686 to 2613 B.C. He directed that a pyramid be made for him, and the resulting stepped tomb in Ṣaqqārah pretty well secured the king's name in history.

As for Imhotep, he's often pinned as the architect who designed the stepped pyramid, though there's no direct evidence of this. His name shows up on multiple monuments, often with honors like "royal seal bearer" and "great of seers," and he was known to be involved with design and sculpture. Imhotep's reputation continued long after his death. In fact, only a century after Imhotep's life, he was even venerated as a god in some circles, Britannica reports. It's a strong indication that the real Imhotep was a big deal.

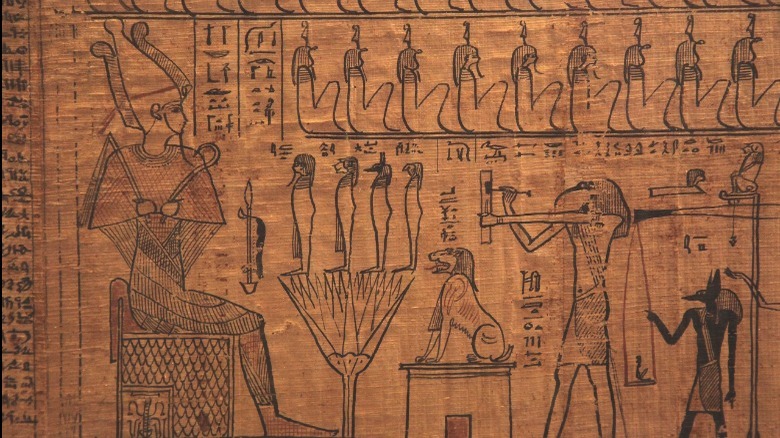

The Book of the Dead is real — kind of

In "The Mummy," the "Book of the Dead" is an evil-looking book that is inadvertently used to resurrect an undead villain. There's also a counterpoint to the "Book of the Dead," the "Book of Amun-Ra," which ultimately sends the big bad villain back to the underworld.

While there is no such book (bound books wouldn't even be a thing until the sixth century A.D., according to the University of Pittsburgh), there really was a set of ancient Egyptian texts called the "Book of the Dead." The American Research Center in Egypt reports that this "book" is actually a collection of papyrus texts that were written by a number of different authors. Also known as the "Book of Going Forth By Day," these texts were intended to help newly dead souls make their way safely through the trials of the afterlife and into paradise. They drew on already longstanding funerary traditions and excerpts of the passages, and prayers inside were often recorded elsewhere, including on mummy wrappings and tomb walls.

It wasn't until 1842 that Karl Richard Lepsius, an early Egyptologist, first assembled these disparate texts as a single document, according to National Geographic. Lepsius' organization of the texts gave the impression that they were all from a single, cohesive document, leading some to the idea that there was a definitive "Book of the Dead" as seen in the film.

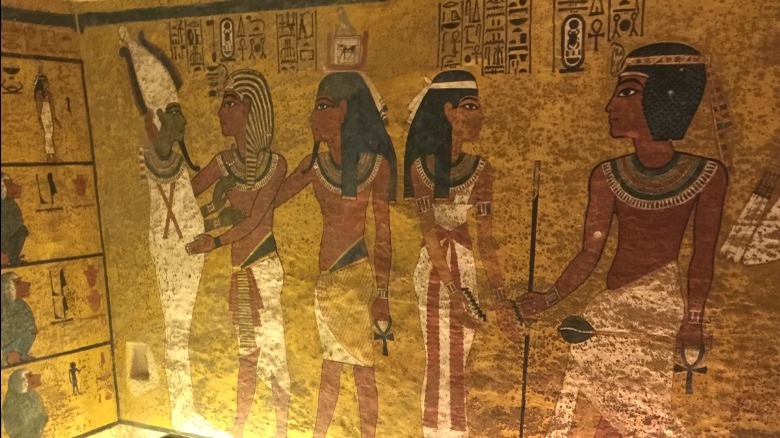

Anck-Su-Namun is named after a real princess

The Hollywood version of Anck-Su-Namun is an ancient femme fatale. Yet, there's a grain of truth to her presence on screen, starting with her name. The real Ankhesenamun was the daughter of 18th Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten, a pretty notorious and quasi-heretical king of ancient Egypt. According to World History Encyclopedia, Ankhesenamun was first called Ankhesenpaaten, meaning "she lives through Aten," in reference to her father's worship of a single sun-centric deity, Aten. It appears that Ankhesenamun had a very close relationship with her father, even being named one of his brides.

After Akhenaten died in 1336 B.C., the cult of Aten collapsed, and much of Egypt reverted back to polytheistic worship. Surviving members of the royal family cut the "aten" out of their names, including another child of Akhenaten, Tutankhaten. The boy, who was his father's successor, renamed himself Tutankhamun and married Ankhesenamun, his half-sister.

After the death of Tutankhamun, Ankhesenamun's story became more mysterious and difficult to follow. Smithsonian explains that she declined to marry the next king, Ay, who may have been yet another relative of hers. She attempted to marry a foreign Hittite prince, but the prospective husband was killed before he could reach her. That's the last anyone knows for sure of Ankhesenamun, although there's plenty of speculation about her ultimate fate.

Anck-Su-Namun's dress isn't that inaccurate

Anck-Su-Namun first appears in "The Mummy" in little more than some gold and black body paint, along with some strategically placed strings of beads and bits of gold plating. While there's no evidence that harem women were painted to ensure that no one else touched them, it is true that sometimes large harems were part of the royal household. However, as "Daughters of Isis" notes, these harems were often more like quasi-independent estates with their own income streams, though they certainly came with some restrictions.

As for Anck-Su-Namun's attire, ancient Egyptians could be surprisingly libertine with their clothing choices, especially when it came to high-ranking women. Her dress (or lack thereof) actually has a historic precedent in real beaded dresses worn by ancient women. Fashion History Timeline reports that decorative beadnet dresses were probably worn over linen shifts or worked directly onto a fabric base. However, it also says that researchers are divided on the point, with some suspecting that the beadnet dresses may have been worn alone.

World History Encyclopedia reports that ancient Egyptians didn't necessarily worry about covering themselves in the same way that Western societies do today. Women wore skirts without tops or light linen tunics, well-suited to the hot, dry climate. Given how the ancient Egyptians seemed generally unafraid of exposing the human form, Anck-Su-Namun's beaded ensemble remains well within the bounds of historical accuracy.

Some people really were mummified alive

Perhaps one of the most unbelievable things in "The Mummy" is Imhotep being mummified alive. After all, as per the Smithsonian, ancient Egyptian mummification involved the removal of vital organs like the lungs, heart, and brains, so there's no way that anyone was ever mummified alive. Right?

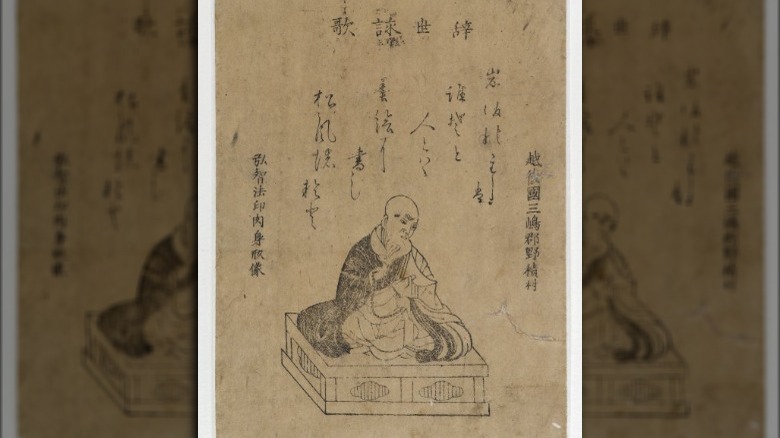

Well, yes and no. There's no evidence that any ancient Egyptian person was still alive when the mummification process started. But the practice of becoming a mummy while alive is a documented tradition in some Buddhist countries, where it was part of a very serious religious ritual practiced by monks. In Japan, the now-defunct practice is called sokushinbutsu, according to Atlas Obscura.

Adherents of the Shingon sect of Buddhism attempted self-mummification between 1081 and 1903 A.D. Generally, the process took at least three years, involved a diet of foraged food, and required intensive meditation. The intention was to purify a monk's spirit and also to winnow away any fat or water that would contribute to decomposition. As part of the process, some monks drank tea made from a tree that was also used to make lacquer, which was both toxic and may have acted as an antibacterial. Towards the end of the process, the self-mummifying monk was lowered into a pit. Other monks would seal the opening and later check if the process was a success. The last known sokushinbutsu was Bukkai, a monk who died in 1903, long after the Japanese government had banned the practice.

Evy's work as a librarian is connected to genuine academia

While "The Mummy" likes to make pretty quick work of Evelyn "Evy" Carnahan's nerdy persona, turning her from a buttoned-up librarian to a somewhat sultry adventurer, her time in the library is much closer to the truth than the movie's fictional city of Hamunaptra.

Though it may be hard to spot while the film is running, the Manchester Museum notes that eagle-eyed viewers can spot some accurate historical details. Evy is first seen managing a series of bound reports from the Egypt Exploration Society, a real organization that was originally known as the Egypt Exploration Fund before changing names in 1919. Given that the film's "modern" setting is in 1926, that's a nice little detail.

Evy's also spotted reading some real-life books from the time period, including "The Dwellers on the Nile," which was published in 1885. By the 1920s, there was already a well-established academic history of Egyptology that would have kept Evy's library busy. According to Britannica, the field is generally acknowledged to have begun when Napoleon invaded Egypt and Syria, from 1798 to 1801. Along with all of the conquering forces, Napoleon brought along scholars who then shared their field research with the European intelligentsia. The discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922 further increased public interest in ancient Egypt, according to the National Trust.

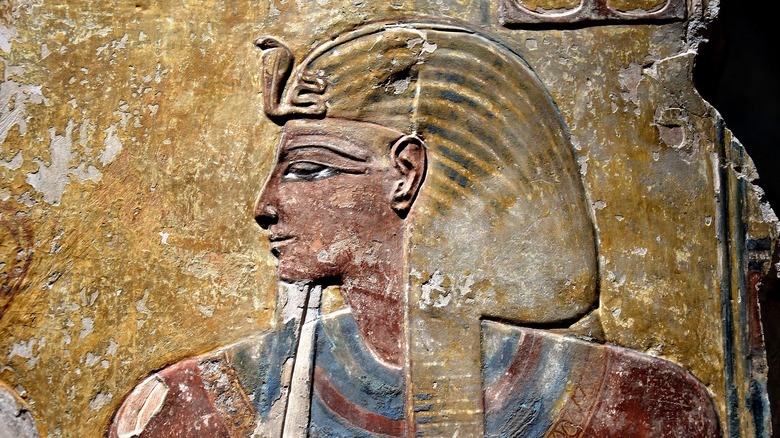

Seti was a genuine pharaoh

The man who arguably sets off the events of "The Mummy" is the ultra-jealous pharaoh Seti I. He is soon murdered by the devious Imhotep and Anck-Su-Namun, but it's his actions that set up the series of disasters that reach all the way to 1926 and beyond.

In reality, Seti I was a 19th Dynasty pharaoh, meaning that he lived centuries after the real Imhotep's death, according to Britannica. He's was a true empire builder, fighting the enemies of ancient Egypt, updating the nation's infrastructure, and building a series of eye-catching structures. Far from being a one-note plot point, the real Seti was kind of a big deal in ancient Egyptian society.

Seti I wasn't killed by his retainers — as far as anyone knows — but researchers are now pretty certain that one of his successors really was murdered by people close to him. The "harem conspiracy" of Ramesses III's reign was perpetrated by a group of harem women who, working with other members of the royal household, conspired to kill the aging king and crown prince and replace them both with a secondary heir (via National Geographic). The conspiracy failed, and the conspirators were executed, proving, perhaps, that "The Mummy" is right: you never really escape the consequences of killing a pharaoh.

The Medjai were a real group referenced in ancient Egypt

Also written as Medjay, the Medjai were first referred to by ancient Egyptians as a group of nomads from nearby Nubia, according to University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons. At first, they weren't the desert-based commandos portrayed in "The Mummy," but it's understandable how the movie got to this representation.

Over time, the word Medjai was transformed from the name of a specific people into a word for a sort of ancient security force used to protect especially valuable areas like royal tombs, per the Journal of Egyptian History. It was no longer an ethnic designation — which was admittedly already very vague, given the dearth of specific Egyptian sources — but an occupational term. By the New Kingdom, the Medjai were like ancient police officers or, perhaps more romantically, traveling desert rangers. They became known for protecting royal tombs and palaces, as well as the nation's borders.

"The Mummy" shows Medjai protecting Hamunaptra in 1923, but in reality there are no records of modern Medjai. According to the Journal of Egyptian History, the last known primary source that references the Medjai comes from the 17th Dynasty. According to "The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt," that time period ended by 1550 B.C.

The temple architecture isn't as overblown as you may think

Surely, you may think, the sets of "The Mummy" are a Hollywood invention. They must be so exaggerated from the original historical sites that the look of the film is far removed from reality.

Not exactly. Depending on the time period, ("The Mummy" plays fast and loose with ancient history), temple architecture in ancient Egypt could be downright gaudy and not unlike a dramatic Hollywood set.

As World History Encyclopedia notes, much of the most elaborate religious architecture was intended to both appease the gods and impress both Egyptians and outsiders. Quite a few rulers of the New Kingdom built their reputations on grand architecture, including Amenhotep III and Hatshepsut, a long-reigning female pharaoh. According to PBS, Ramesses II was especially fond of structures packed with inscriptions, carvings, and statues. He even went as far as "improving" earlier structures with his energetic architectural drive. Given all of the embellishments, sprawling structures, and huge statues that Ramesses and his royal associates enjoyed, they may well have nodded in approval at the excesses of Hollywood set design.

Curses were a part of ancient Egyptian religious beliefs

Curses are a much-discussed topic in the world of Egyptology. There is, of course, the now infamous King Tut's curse, which supposedly brought awful luck to the team who opened Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922. However, a closer look at the circumstances of the so-called curse shows some pretty inconsistent evidence, including the fact that Howard Carter, the archaeologist who helmed the excavation, lived for 17 years after opening the tomb.

That said, while stories like King Tut's tomb curse are pretty overblown, archaeologists have found some curse-like inscriptions in ancient Egyptian tombs. However, as National Geographic reports, they're pretty rare and only directed at people with ill-intent, such as threatening grave robbers with a crocodile or scorpion-related demise.

Ancient Egyptians weren't above cursing each other via magic, according to "The Process of Cursing in Ancient Egypt." Examples include magic spells recovered from scraps of papyrus and pottery, as well as execration figurines meant to represent the object of a curse. The practice of destroying someone's name to deny their immortality via memory is also documented, a ritual that is done to Imhotep at the beginning of "The Mummy."