The History Of Egypt's Valley Of The Kings Explained

The pyramids are rightly Egypt's most famous monuments. Built during the Old Kingdom, they served as grand tombs for the Egyptian pharaohs. This period, as described by the World History Encyclopedia, is sometimes called the "Age of the Pyramids" and lasted from 2613 to 2181 BC.

The pyramids, however, are in many ways less rich for archaeologists than other sites in Egypt. The most notable of these sites is the famous Valley of the Kings, which has offered and continues to offer new insights into ancient Egypt. This necropolis, or collection of hidden tombs, was built, according to National Geographic, during the New Kingdom (1509 to 1075 BC), which was centuries after the pyramids. To put this in context, to people of the New Kingdom, the Age of the Pyramids was as remote to them as the Middle Ages is to us today.

Let's take a look at and explain the history of Egypt's fabulous Valley of the Kings, starting with why it was created.

Tomb raiding led to the creation of the Valley of the Kings

The grandeur of the pyramids and the treasures locked inside were their undoing. As the World History Encyclopedia describes, the pyramids and other gravesites became the target of tomb robbers. To try to prevent robbery, the ancient Egyptians designed pyramids to keep out looters, even filling in hallways with debris. Many tombs even featured curses. This had little impact, as over the centuries, all the pyramids were plundered of their treasures, which included the mummies themselves. Part of the problem was that the highly visible pyramids might has well have had flashing "plunder me" signs on them.

Tomb robbing was a major dilemma, since Egyptian religion believed that the body of the dead needed to be as whole as possible in order to successfully transcend into the afterlife. In the case of a pharaoh, he (or sometimes she) needed to also have all the royal accoutrements attached to the position of god-king.

The New Kingdom pharaoh Amenhotep I of the 18th Dynasty (c. 1541-1520 BC) decided that a new, secure location that was less obvious than the pyramids was needed to protect the tombs. Thus, Amenhotep commissioned the building of a special village originally named Set-Ma'at, but today called Deir el-Medina, to construct a new necropolis.

How the Valley of the Kings was built

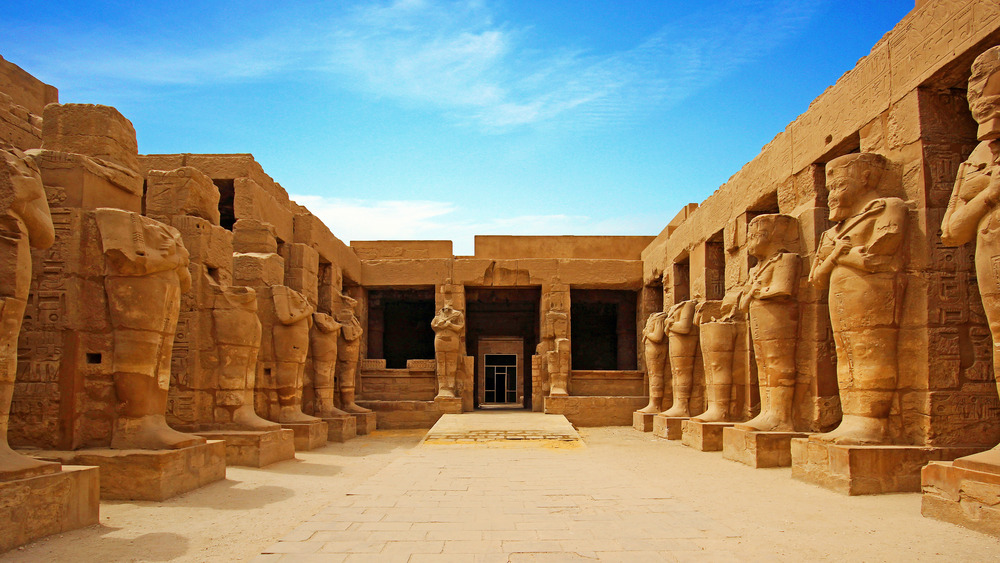

The ancient Egyptians chose to build their new necropolis in the "red land," a term which, as explained by the Canadian Museum of History, signifies the reddish desert. This is opposed to the rich, arable "black land" adjacent to the Nile River. The proposed location, opposite the ancient city of Thebes (now Luxor), was carved out of the Theban massif, according to the Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Perhaps the pharaohs were attracted to the peak, which recalled the shape of the great pyramids. Aside from its fairly remote location, the Valley of the Kings had another security advantage. As related by The Great Courses Daily, there was only one entrance to the valley, which would be easy to guard.

That is where Deir el-Medina came into play. It was thought, as explained in the World History Encyclopedia, that the new town would help provide security as well as maintain discretion as to where the pharaohs and their treasures were interred.

The Place of Truth

As mentioned, Deir el-Medina was called Set Ma'at by the ancient Egyptians. This meant "The Place of Truth." The World History Encyclopedia reveals that it was given the name by the belief that the artisans who worked there to build the tombs were inspired by the gods. Those who lived there were called "Servants in the Place of Truth." Because the village was to be set in the harsh environments of the red land, it was, unlike other Egyptian settlements, entirely preplanned. It was designed in a rectangular pattern with a dense arrangement of housing to maximize space. Since it was in the middle of the desert, it had no resources to speak of, except that which was shipped in. Also, since all the inhabitants of Set Ma'at were tomb workers, there was no agriculture. As a result, they were entirely dependent on the largesse of the ancient Egyptian government to furnish their needs, even water. Despite these difficulties, the village was founded, and the artisans began their work with bronze and copper chisels.

The first pharaoh to be buried in the Valley of the Kings was Tuthmosis I (Thutmose I), the successor of Amenhotep I. The construction was overseen, as detailed by the Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings, by an advisor named Ineni. This was the beginning of a long tradition of tomb-building throughout the New Kingdom.

The mummies of the Valley of the Kings

The ancient Egyptians believed in an afterlife that was a mirror image of our living world. The physical body was critical for passage into the afterlife, into what they called the Field of Reeds, according to the World History Encyclopedia. Yet before crossing to the afterlife, the soul was thought to be trapped in the physical body and needed to be coaxed out. As a result, the ancient Egyptians conflated spirituality and physicality. Embalmers kept busy preserving the dead through elaborate rituals and eviscerations. As detailed by Smithsonian Magazine, the entire process took about 70 days, during which the dead pharaoh's organs were removed and placed in special canopic jars before the corpse was covered with salt to prevent decay. By the time of the New Kingdom, the art and science of embalming had become so advanced that the mummies of that period are among the most well-preserved today. This is also undoubtedly due to the well-designed tombs found in the Valley of the Kings.

The Valley of the Kings is home to some of the best known pharaohs and elites of ancient Egypt, as detailed by National Geographic. Seti I, Ramses II, and the boy-king Tutankhamun were all entombed in the Valley.

What else is buried in the Valley of the Kings?

Because the ancient Egyptians believed that physical bodies would become reanimated, they stocked the tombs with things needed both for pleasure and practicality. National Geographic details that these items included not just treasure but also food and alcoholic beverages for presumed ghostly royal feasts. Changes of clothes, including fresh underwear, were included, as well as furniture to sit on. Archaeology Magazine reported that archaeologists found one of the earliest known sundials in the Valley of the Kings. Apparently, the deceased cared about time as much as the living in ancient Egypt.

The dead were also joined by animals — lots of them. The journal Nature catalogs numerous animals that were mummified. Some were for food. Others, such as ibises, hawks, and crocodiles, were embalmed as sacrifices — an interesting notion. Still more were just pets, such as cats, baboons, and dogs. In fact, there were more animal mummies than human mummies, although, admittedly, the preservation methods used to embalm animals were more slipshod.

The Valley of the Queens

While the Valley of the Kings is justly famous, another major necropolis, just adjacent to the site, is the Valley of the Queens. According to Britannica, the site contains over 90 tombs, that we know about. The Valley of the Queens is also, as described by the Getty Conservation Institute, in close proximity to the pyramid-shaped Theban peak and contains a sacred grotto that was probably dedicated to the goddess Hathor.

These tombs were the site for Egyptian officials before becoming the interment chambers of the Egyptian queens, as well as other elite women of the New Kingdom. They are not as elaborate as those found at the Valley of the Kings and usually consist of short halls and sarcophagi chambers. Notably, these tombs also tend to be devoid of description and decoration, making it difficult for Egyptologists to identify who was buried where. Still, scholars have been able to identify several famous residents of the Valley of the Queens, such as Nefertari, the favored queen of Ramses II. The location was called Ta Set Neferu, meaning "The Place of Beauty," by the ancient Egyptians.

The Looting of the Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings was thought to be secure from the robbery that plagued the pyramids. According to the World History Encyclopedia, hopes rested on Deir el-Medina (Set-Ma'at) as the artisanal village that was purposefully created to build and care for the tombs. It was thought that since the village was built deep in the desert and entirely dependent on the government for supplies, wages, and housing, and since the residents would have pride in their own work, that the people of Deir el-Medina would protect and keep secret the tombs of the Valley of the Kings.

These assumptions were wrong. Deir el-Medina's supplies were rationed, and everybody received generally the same allotment of goods, including the water that was brought in from the Nile daily. It wasn't luxurious living, and the workers soon gave into temptation and broke into tombs, taking treasure to sell it off at the nearby city of Thebes. As the New Kingdom wound down, conditions worsened, and robberies grew despite punishments which included forced amputation, torture, and execution. At one point, the situation was so bad in Deir el-Medina that the workers actually staged the first strike in Egyptian history. According to the New World Encyclopedia, at the end of the New Kingdom, the situation became so grim that priests removed royal mummies and treasure and reinterred them at mass sites.

The tomb hunters

Throughout the rest of antiquity, the tombs were unused, although, according the New World Encyclopedia, they were often visited by Roman and Greek tourists who inscribed graffiti on the stonework. After the rise of Christianity, some of the tombs were even used as Coptic churches. By then, all the known tombs had been ransacked.

Interest in the Valley of the Kings virtually vanished until the 18th century. It was then that Europeans found and began to explore it. Exploration continued into the 19th century, in part propelled by the successful translation of Egyptian hieroglyphics. It was during this time that Europeans started designating tombs with numbers preceded by "KV."

New tombs were being found and explored. This was no mean feat, as some of the tombs were quite extensive. The Theban Mapping Project of the American Research Center in Egypt has created detailed blueprints of the royal tombs. Some, such as KV5, which was for Ramesses II's sons, has well over 100 individual chambers. KV5 is the largest tomb in the Valley, but it is demonstrative of the intricacies and work put into building them. It also shows the difficulties in exploring them.

That brings us to the most dramatic discovery in the Valley of the Kings: Tutankhamun's tomb.

King Tut's tomb

The most famous and fabulous discovery in the Valley of the Kings occurred in 1922. As described by National Geographic, by the end of the 19th century, archaeologists believed that the Valley had yielded all its secrets. However, British archaeologist Howard Carter suspected otherwise. In 1922, he discovered the tomb of what was then an obscure boy-pharaoh of the 18th dynasty — Tutankhamun. To Carter's delight, he found that the seals on the tomb were unbroken. What probably saved this tomb from robbery was King Tut's relation to Akhenaten, his predecessor who tried to overthrow traditional Egyptian polytheism with monotheistic sun worship. After Tutankhamun's death at age 15 or 16, later rulers tried to erase the memory of the blasphemous dynasty, even though Tutankhamun restored traditional religion. His tomb was later hidden by flood debris.

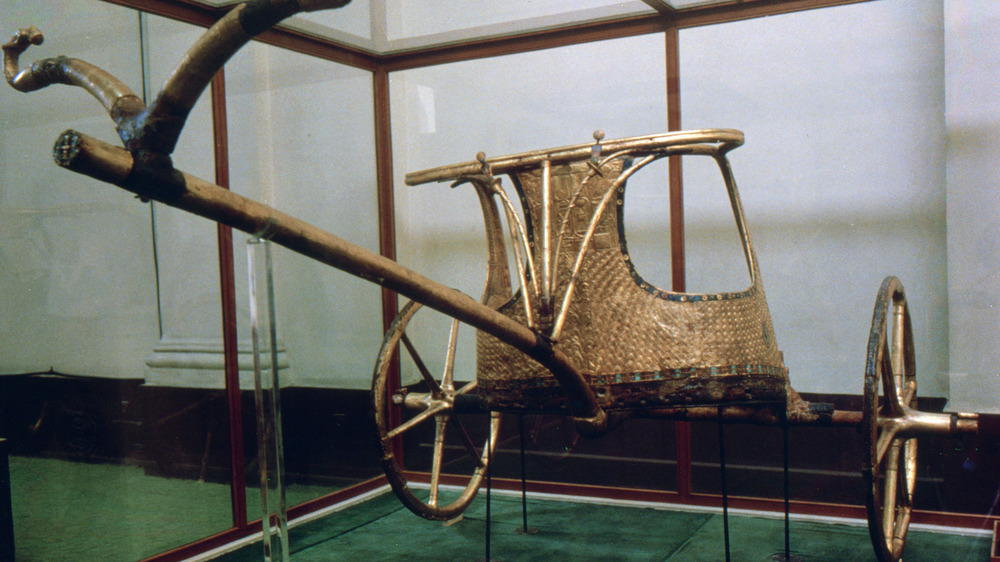

The thousands of artifacts found in King Tut's tomb dazzled not just Egyptologists but the people around the world. HistoryExtra catalogs just a smattering of these treasures, such as lapis lazuli scarab beetles, golden flails and crooks representing pharaonic authority, a gold chariot, a gold mask, and gold sandals. Alongside these glamorous grave goods were the practical supplies. The BBC states that among the 5,000 objects found in the tomb were baskets of chickpeas, lentils, and dates, as well as bread and meat. What's more, the assembly of statues and other religious paraphernalia enhanced our insight into the worldviews of ancient Egypt.

The lost tombs of the Valley of the Kings

Even though the Valley of the Kings has been excavated for centuries, it is widely believed that there are still major tombs to be found. As National Geographic explains, there are several prominent royals from the New Kingdom whose tombs have not been located, including Ramses VIII. To find a tomb, archaeologists usually comb through historical records looking for unaccounted elites to whom no tomb is attributed. National Geographic quotes David P. Silverman, an Egyptologist from the University of Pennsylvania: "You try to find out what hasn't been discovered, and figure out where they might possibly be, and then look in those areas. You never know what you are going to find."

Excavations, meanwhile, aren't limited to the Valley of the Kings. Of equal, but different, importance is the work being carried out at Deir el-Medina. Macquarie University emphasizes that although the town wasn't a typical ancient Egyptian village, the unique preservation qualities of the desert environment has allowed a large array of artifacts to survive to the present day. One of the most important artifacts are ostraca, which are ceramic shards with inscriptions such as poems, caricatures, and matters of business. Through this, we have learned much about how ancient Egypt functioned as a society.

New Discoveries at the Valley of the Kings

As archaeologists continue to work at the Valley of the Kings, new discoveries are still occurring. As described by Smithsonian Magazine, the first tomb to be discovered after Tutankhamen was found in 2006 and dubbed KV63. This tomb, although not believed to be a royal tomb, has encouraged further exploration with the ultimate hope that a tomb like King Tut's may be discovered.

In 2019, Live Science reported the discovery of additional mummies and workshops, which provided more insight into the lives of the commoners of ancient Egypt. Then Nature reported in 2020 that a ground-penetrating radar survey in the areas adjacent to Tutankhamen's tomb have revealed the possibility of deeper chambers. Archaeologists have speculated that this may be the burial chamber of the famous Queen Nefertiti, whose daughter was married to King Tut and who briefly served as pharaoh. Nature quotes British Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves as saying, "If Nefertiti was buried as a pharaoh, it could be the biggest archaeological discovery ever." Others Egyptologists, such as Egypt's former antiquities minister Zahi Hawass, contend that no major discovery has been found that way. He is continuing his own explorations using traditional methods.

Conservation of the Valley of the Kings

The significance of the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens to history and our understanding of the past is obvious. Since 1979, both sites have enjoyed the status of being UNESCO World Heritage Sites, with the original declaration stating that it "certainly merits recognition, and seems to be indisputable from the point of view of the world heritage."

The site has, therefore, been closely monitored for decades. You would think with that level of scrutiny, the conservation of the Valley of the Kings would be assured. However, a 2019 report by UNESCO on the state of preservation cites erosion, rising underground water levels, and human development as factors which threaten the site. One of the largest threats is tourism. The World Monument Fund notes that 1.5 million tourists visit the Valley annually. These tourists are a direct cause of deterioration of the site. They note, "...while every traveler deserves an opportunity to see this spectacular site, measures must stay in place to ensure that eager visitors are aware of the fragility of the ancient tombs."

It is a delicate balancing act between the preservation of these ancient tombs that survived the millennia and the desire of modern to look into the past. Hopefully it can be achieved while simultaneously gleaning more insights and treasures from ancient times.