True Stories Of The First Railroad Accidents Everyone Forgot

If you've ever ridden the rails on Amtrak or a commuter train, you might wonder just how and when the "Iron Horse" came along to make travel faster and easier. Surprisingly, although Americans are more familiar with the steam locomotives that made their appearance during the 1800's, what is considered the first railroad accident actually occurred in England way back in 1650. However, that was a tram used for inner-city transportation, not the large several-car trains we see today. Not until 1804 was the steam engine launched, making railroad travel possible. Notably, however, those first trains could only travel around 10 mph.

Train travel has come a long way, with today's "speed" trains zooming along the tracks at an amazing 300 mph. Fine-tuning the railroad system, however, has been a true trial-and-error process, with lots of messy accidents along the way. History cites the first railroad mishap in America as happening in 1832 in Massachusetts, with one fatality. And the worst train accident to date happened in 1918 in Tennessee when over 100 people were killed. It's actually quite amazing just how many train crashes have occurred throughout our history in the name of improving rail service. Read on for some stories of some memorable firsts in railroad accidents that everyone has forgotten.

Train manufacturers dabbled with train cars and tracks for decades

A lot of thought and design has gone into the use of railroads lo these many years. American Rails says the "founding era" of railroads in the US actually began in the late 1820's. The first train company to design cars for passenger transportation was the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in 1827. A neat fact is that Charles Carroll, the only remaining survivor to sign the Declaration of Independence, was chosen to lay "the first stone" when construction began the following year. But by 1830 the track was only 13 miles long.

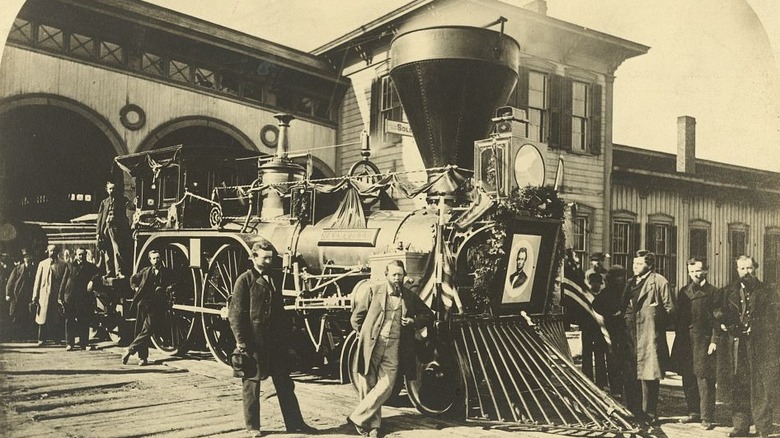

Ten years later, in 1840, there were almost 3,000 miles of track in the eastern US. The number would grow to three times as much within another decade. Railroad engineers, meanwhile, debated over whether standard gauge or narrow gauge tracks were better, as George Pullman mulled over how to make "sleeping cars" available to overnight train passengers. The sleeping car quickly grew in popularity when one was used to transport the body of Abraham Lincoln after he was assassinated in 1865. Four years later the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads combined to create the Transcontinental Railroad as the tracks began heading to the western US.

The first head-on collision in America happened in Virginia

According to RailServe, America's first train fatality happened in 1833 in New Jersey due to a broken axle. Two died and dozens were injured. But that was nothing compared to the very first head-on collision between two trains in 1837. The Native American newspaper explained that a daily train with 13 passenger cars had left Portsmouth, Virginia with around 200 passengers when it crashed into a lumber train. The weight of both trains crushed two passenger cars as others derailed.

Although Disasterous History surmises the trains were only traveling at between 12 and 20 m.p.h., the carnage was great. Neighbors heard the sickening screech of the wheels on the rails and the splintering explosion of wood and other materials as the cars disintegrated all around the tracks. Three young ladies, Elizabeth McClenny, Jemima Ely, and Margaret Roberts, were killed and several more were wounded. To make matters worse, a rescue engine headed to Suffolk in a blinding rainstorm ran over James Woodover and Richard Oliver, killing them too. An inquest found the "agent" of the lumber train responsible for the first accident after failing to pull into a siding as scheduled. Mr. Culpepper, the engineer on the rescue train, was exempt from any blame.

President Franklin Pierce's son was killed just after he was elected

Writer Julie Mofford explains that Franklin Pierce and his wife, Jane, had already lost two sons when a third child, Benjamin, was born in 1841. At Jane's request, Franklin resigned from politics but was successfully nominated as the fourteenth president in 1852. Two months later, in January of 1853, the Pierce family had been at a funeral when they boarded a train for their home in New Hampshire. But just minutes after the train left the station an axle broke and the train derailed. Franklin and Jane watched in horror as young Benny was "nearly decapitated" and died.

In reporting the accident, the New York Herald said that although others were injured, Benny was the only casualty. Jane was so distraught that she couldn't attend his funeral. She also blamed her husband's politicking for the incident. No wonder the president entered the White House "nervously exhausted" after refusing to swear on the Bible at his inauguration, blaming himself for Benny's death and claiming God was punishing him for pursuing politics. During Franklin Pierce's only term Jane became known as "The Shadow of the White House" who wore black and refused to attend functions. She died in 1863. Pierce drank himself to death six years later.

The earliest train wreck to be photographed happened in 1853

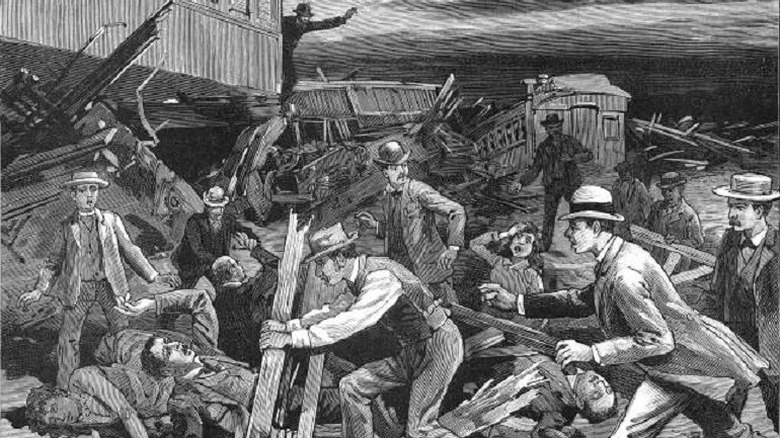

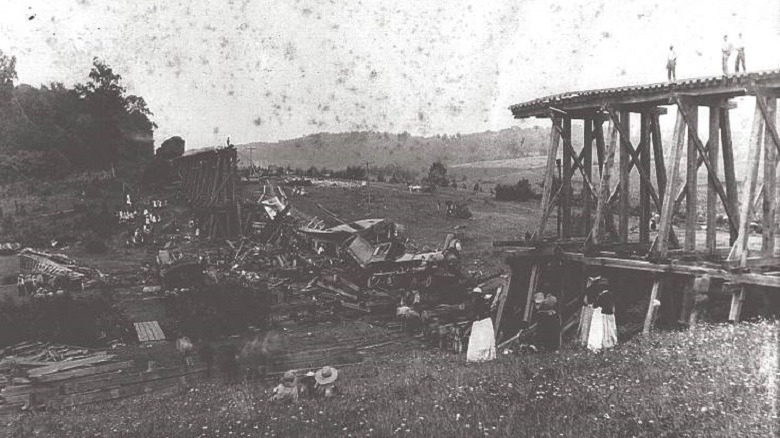

Just over seven months after young Benjamin Pierce was killed, another train crash made national news. This one happened in Rhode Island when a southbound Providence and Worcester train hit a northbound train head-on. The southbound was running late; the northbound had pulled into a junction to wait but decided to move on upon seeing the track was clear. Both engines were demolished as the other train cars were smashed to bits. Both the injured and the dead were brought out of the wreckage as a Boston train stopped to help, says Gen Disasters. Also on hand was an unidentified photographer who, according to Kodak, made history for recording one of the first images of a train wreck (pictured).

In the coming weeks the New York Herald would give an extensive report on the crash, but the Illustrated News one-upped the newspaper with two wood-engraved views of the carnage in which more than 10 people died. A Coroner's Jury found that although conductor F.W. Putnam of the southbound train was to blame for running late, the railroad itself was at fault. Young Putnam had been forced to use "a poor borrowed watch" due to the fact that the train company only paid him $30 per month. The cheap watch didn't keep proper time.

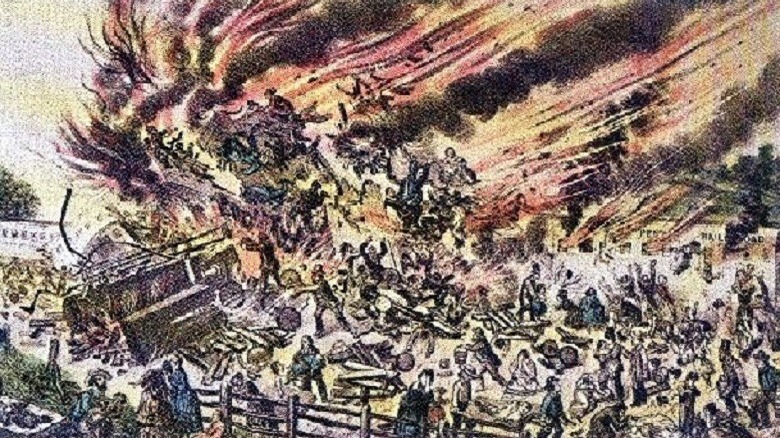

Victims of The Great Train Wreck of 1856 were mostly children

On an early July morning in 1856, children from a Sunday school at Philadelphia's St. Michael's Catholic Church boarded a North Pennsylvania Railroad train for an excursion to Fort Washington for a picnic. Devastating Disasters puts the number at 1,500 kids. The train was already 20 minutes behind when it pulled out of the station. At another station up the tracks a bit, the conductor of a passenger train carrying 20 people aboard knew the children's train was due, but only waited 15 minutes before pulling out anyway. It was a disaster in the making.

By the time the engineers of the two trains saw each other near the Camp Hill Station, the excursion train was going too fast. The two collided and a boiler exploded as the Sunday school train was blown off the tracks. Gen Disasters says the sound of the explosion could be heard five miles away. Tragically, nobody seems to know just how many were injured or died. The Davenport Daily Gazette put the number at 39 fatalities and 100 injured, and the Hillsdale Standard counted Father Sheridan from the school among the dead. Explore History puts the number at 60 injuries and 60 dead. All that is known for sure is that the conductor of the passenger train took the blame for the accident and completed suicide later that day.

There were two devastating train wrecks during the Civil War

Railroads proved quite useful for transporting troops during the Civil War. In September 1863, for instance, 20,000 troops were sent by train from Washington, D.C. over 1,200 miles to the Battle of Chickamauga in Georgia in only 11 days, says History. Unfortunately, train travel, like any other mode of transportation, was subject to terrorism. In 1861 in Mississippi, "southern bushwhackers" managed to "undermine" a bridge across the Platte River. Minutes later a Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad train was on the bridge when it collapsed, killing upwards of 20 passengers.

Another tragedy happened in 1863, also in Mississippi. This time, the Chunky River was already at flood stage when a train on the Southern Rail Road tried to cross a damaged bridge. Failing to see the warning lanterns, the cars derailed on the bridge sending over 100 people, mostly Confederate soldiers, into the icy waters. Most of them died on impact. Most unique were the victims' rescuers, the First Battalion of Choctaw Indians, under Major S. G. Spann. The Natives rushed to the site and dove in to save as many as they could. Many of the dead were buried in trenches at a local farm. Today there is a plaque at the site.

New York's Angola Horror wreck in 1867 brought safety changes to rail travel

In her book, "The Angola Horror: The 1867 Train Wreck That Shocked the Nation and Transformed American Railroads," Charity Vogel explains that a New York Express train was traveling along on the morning of December 18, 1867 when it hit what is known as a "frog" on the track and clipped a metal spike before two passenger cars on the back fell off the tracks and tumbled down an embankment. Inside, says History Net, the alarmed passengers, as well as numerous pot-bellied stoves for warmth and kerosene lamps for light, were thrown all over the cars. Some were crushed. Others were burned alive.

Witnesses at the scene did their best to save those they could, to little avail. Some 50 or so people died that day, their bodies burned beyond recognition. Quite by happenstance, American business magnate John D. Rockefeller had actually missed the train that morning although he came upon the accident on a later train. The victims were buried in a mass grave that bears no marker, and Train Web verifies the wreck was caused by a difference in the width of the tracks. WBFO says the tragedy led to prohibiting wooden passenger cars and "open stoves" and led to "standardization of track widths" and the invention of air brakes.

The Great Revere Train Wreck of 1871 killed over two dozen people

On the evening of August 26, 1871, a train on the main line of the Eastern Railroad was chugging towards Revere, Massachusetts. According to American Heritage, four different trains along the line were soon running late. As one train, the Portland Express, bore down on the depot, the engineer thought the lights he saw were from the station. In reality, they were lamps on another train that was stopped. As the Portland ran into the back of the other train, the steam boiler exploded.

Within seconds, explains Greener Pasture, some dozen people were thrown all over the train cars. Some were crushed while others were scalded to death by the blown boiler's water. Still others died as the coal-oil lamps in the passenger cars caught the whole mess on fire. Rescuers tried to pry the roof off of one coach to rescue the victims, but in all 29 people died. A jury found the conductor, engineer, the station master at Boston, and several others guilty of negligence. As in the case of the "Angola Horror," kerosene lamps were thereafter forbidden on Eastern Railroad trains.

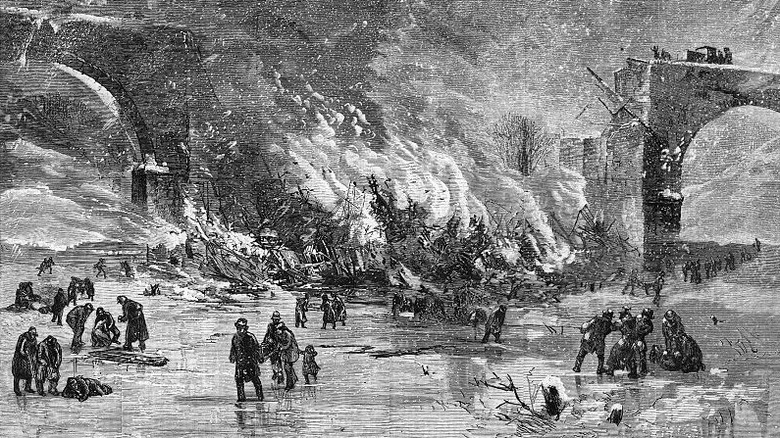

The Ashtabula River Railroad Disaster is the deadliest bridge disaster in US history

In 1840, William Howe invented the "Howe Truss," a railroad bridge that was designed to carry more weight. Although some of the trusses were originally made with wood and metal, the one on the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway near Ashtabula, Ohio was the first constructed of all metal. That didn't help the Pacific Express, No. 5, however which 35 Bridge says was crossing the truss with two locomotives, 11 cars, and 159 people aboard on a December night in 1876.

Three of the rail cars were passenger coaches according to Ohio History Central. As the train went over the bridge, those on board heard "a terrible cracking sound" as the truss collapsed under the weight of the train. Every car but the locomotive plunged into the creek below and immediately caught fire. Like other wrecks before, the conflagration was caused by stoves and lamps burning inside the cars. Somewhere between 83 to 98 died. Approximately 60 more were injured. It was the deadliest bridge disaster in American history.

The Great Chatsworth Train Wreck of was caused by a damaged trestle

At midnight on August 10, 1887, says Roadside America, a Toledo, Peoria & Western passenger train was chugging along between Peoria, Illinois on a special promotional trip to Niagara Falls in New York. Two steam engines were pulling six fully loaded passenger coaches, six sleepers, and three baggage cars. What the engineer did not know was that a controlled burn under an upcoming trestle earlier that day had not been completely put out, damaging the wooden structure. As the first engine crossed the trestle it collapsed and the train plummeted to the ground.

Although help arrived to assist the injured, other unscrupulous people actually robbed the dead or took "souvenirs." And of the 500 to 700 passengers aboard, an exact number of the dead remains unknown because the Toledo, Peoria & Western burned the wreckage in its entirety before all of the bodies were recovered. Still, the accident is remembered as "one of the worst" train wrecks in American history, to the extent that a song, "The Chatsworth Wreck," was written about it around 1923. Today, says Chatsworth Illinois Memories, a plaque commemorates the accident.

A collapsed trestle caused the Wreck at the Fat Nancy

According to the Historical Marker Database, "Fat Nancy" was the less than flattering nickname of a Black woman who worked as a "trestle watcher" along the Virginia Midland Railroad. But Nancy was apparently in bed when a passenger train, the "Piedmont Airline," fell at 2 a.m. while crossing her namesake trestle in 1888. The Alexandria Gazette reported that a coach car "broke down" on the trestle, which could not bear the weight of the train. The trestle collapsed and the train fell 40 feet, the engine landing on top of it. It was the worst railway accident in Virginia history.

Three passengers, a mail clerk, and a newsboy were killed outright, although Latitude confirms that a total of nine died and over two dozen others were injured. One of the dead was civil engineer Cornelius Cox who had only recently designed a culvert to replace the trestle. Notable too was that Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet, who had just attended a 25th reunion party for the Battle of Gettysburg, survived. Today, the Light Well in Orange, Virginia features "The Fat Nancy," a "flagship brew" named for the wreck, and Odd Legged Jenny sings a song about it. There is also a plaque at the site for those interested in reading about it.

The train crash at Crush was actually staged but went horribly wrong

For one day only in 1896, Crush, Texas was a "town," the brainchild of the Missouri Kansas Texas Railroad agent W. G. Crush. It was he who suggested promoting the railroad by purposely crashing two trains, head-on, in a remote spot on the plains near Waco. For months, says KWBU, Crush sold train tickets at two dollar per head to travel and see the spectacle. Everything was safe, he said, as engineers on the job promised the train's boilers would not explode. By the day of the event some 40,000 spectators had gathered at the made-up town in anticipation of the event.

There was a four-mile track for the event, plus music, food, a rollicking carnival, and of course a huge grandstand, says Waco History. Spectators were seated 200 yards away, although news reporters were allowed to stand "within 100 yards of the track." The Texas State Historical Association says the two trains drew up nose to nose before backing up to each end of the track. Crush himself waved a white hat as the locomotives started out. The engineers jumped from the trains as they built up speed and crashed head-on. But the boilers did explode, and flying metal injured at least six people as three others were killed. Amazingly, the railroad retained Crush even as the owners settled numerous damage claims.

Casey Jones, engineer of the Cannon Ball Express, went down in history

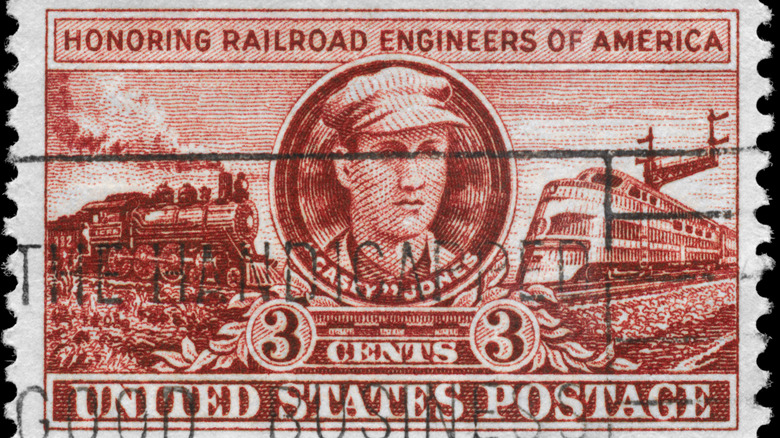

Fans of Johnny Cash and the Grateful Dead will have heard songs about the immortal Casey Jones who has become a legend. Born John Luther Jones in Missouri during the 1860's, Jones' last ride on a train called the Cannonball Express made him a true folk hero.

Biography explains that Jones got his first job for the Mobile and Ohio Railroad when he was just 15-years-old. He quickly moved up the ranks, becoming an engineer for the Illinois Central Railroad in 1891. For the next decade he became known for sometimes driving trains "at dangerous speeds" to keep his schedule. On a fateful day in 1900, Jones revved the locomotive up to 100 mph and crashed into a parked train. Everyone survived but Jones, who "died with one hand on the train's whistle and the other hand on its brake."

Jones was first remembered in Wallace Saunders' song, "The Ballad of Casey Jones," although Lawrence Seibert was first to publish the tune in 1902. Other versions of the songs have since been published and a US postage stamp also pays homage to Jones; meanwhile, Disney featured the engineer's story no less than 15 times between 1950 and 2001.