What You Should Know About Tenochtitlan's Main Temple

Long before al pastor tacos, school days off for soccer matches, and homemade salsa that blows Tabasco out of the water (the sauce, not the Mexican state), Mexico City was a place of ruthless class systems, serpent gods, and heart-extracting human sacrifice. Ok, and a bustling trade center of cacao beans, cotton, gold, jewelry, and more, per Live Science, under the rule of the Aztecs (1325-1521 CE), when it was called Tenochtitlán. Along with Tetzcoco and Tlacopán, the threefold city-state empire ruled modern-day Mexico with a brutality that we might be grateful has been replaced by the down-to-earth charm of Mesoamerica's current leading candidate for having its cuisine poorly imitated across the border (Tex-Mex is not Mex-Mex, people).

Of course, such change came at a heavy, predictably colonial price, as National Geographic recounts. After Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortes rose in power during the conquering of the Dominican Republic and Haiti, and helped conquer Cuba in 1511, he and a mere 500 armor-wearing soldier buddies landed on the Yucatan Peninsula in 1519, where they were simply escorted to Tenochtitlán. There, the Aztec leader Moctezuma and his 5-6 million citizens — who'd heard nothing of the Spanish goings on in the Caribbean — welcomed their visitors, as well as their guns, germs, and steel. That's all it took. In the end, in 1521, Tenochtitlán fell. A mere 100 Spanish were dead, compared to 100,000 Aztecs.

Meanwhile, Tenochtitlán's blood-soaked Templo Mayor ("Main Temple") looked on silently.

The beating, blood-soaked ceremonial heart of Tenochtitlan

"Not a single stone remained left to burn and destroy," National Geographic recounts one witness wrote of Tenochtitlán's fortifications, homes, and what we now dub in Spanish, "Templo Mayor," the city's main temple. And looking at the temple's current, foundational remains in Mexico City, viewable on Archaeology, it's easy to believe.

The main temple that Cortes came across when he infiltrated and leveled Tenochtitlán, Templo Mayor, was in fact the sixth such temple built in place on top of previous, older versions. Each new ruler rebuilt the temple — the ceremonial and cultural heart of the city — on top of the last one like nested matryoshka dolls. And when we say "heart," in this case, yes, we're referring to the aforementioned human sacrifices that took place at Templo Mayor, complete with multiple Tzompantli (skull racks) adjacent to the temple, as Live Science recounts. Decapitations, chopped-off limbs, flowing blood, organ extractions while people were still alive: all such ceremonies took place at Templo Mayor's presumably blood-caked summit.

This curious brutality, not evident in other, nearby peoples, gets a lot of attention precisely because it's such a violent outlier. Perhaps it was the Aztec's mythology and stories, themselves full of decapitations and dismemberments, such as that of the moon goddess Coyolxauhqui, who was mutilated by her brother Huitzilopochtli for disrespecting their mother. Or perhaps it was just a way for the powerful and elite to rule, god-like, over their citizenry.

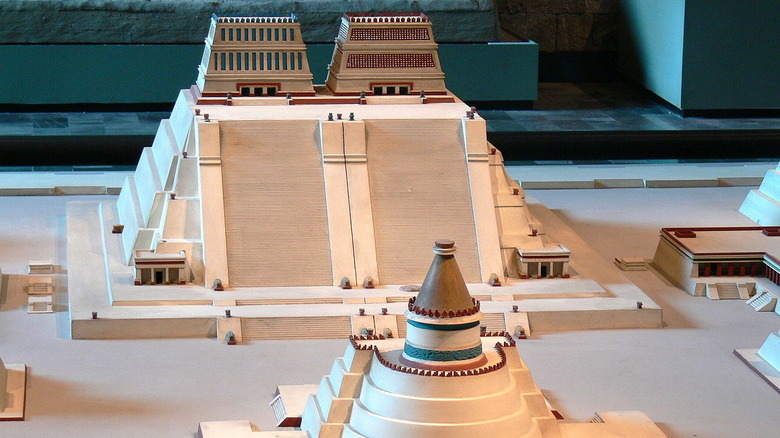

Crowned with twin pyramids representing sacred mountains

When Cortes came across Templo Mayor, or "Huei Teocalli" in Aztec in 1519, it stood 150 feet high, per the BBC. As Universes in Universe describes, there were double stairwells leading from the ground to a main platform on which stood two, smaller pyramids. These represented two mountains: Tonacatepetl on the left, associated with corn and the rain god Tlaloc, and the Coatepec (mountain of the serpents) on the right, which commemorated the aforementioned murder of the goddess Coyolxauhqui by her brother, Huitzilopochtli, the war god. Templo Mayor stood at the center of a symmetrical complex of 78 related buildings in the center of Tenochtitlán. No expenses were spared on these structures.

Templo Mayor's seventh and final shell, like a cap, had been built by Moctezuma on top of the sixth temple built by the Aztec's most ambitious ruler, Ahuitzotl. When Ahuitzotl inaugurated his temple in 1487, 4,000 people were slaughtered over four days. Priests brandished ceremonial daggers and gutted victims, brandishing their still-beating hearts to the sky before kicking their bodies down the temple's steps. Warriors dressed as eagles stood guard. Drums pounded. Red blood poured over the temple's white stone. A decade later, in 1497, Ahuitzotl had doubled the size of his empire, and implemented urban planning, sanitation, running water, and daily baths.

Meanwhile, annual festivals such as those honoring Huitzilopochtli involved eating idols dressed in robes and wearing golden crowns and made from seeds, honey, and human blood.