Charlie Chaplin's FBI Files Explained

After World War II, a wave of anti-communist paranoia went through the United States, led by prominent figures like Sen. Joseph McCarthy, of the now infamous "McCarthyism," and investigated by the FBI, under the direction of J. Edgar Hoover. Due to the prevailing belief that the film industry might be infiltrated by communists looking to create subtle propaganda and corrupt moviegoers, Hollywood was subject to many investigations throughout the '40s and '50s.

The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) called many to testify, forcing them to either "name names" and accuse others of possibly spreading Soviet propaganda, or refuse, like the "Hollywood Ten," who were imprisoned, fined, and ultimately blacklisted, as detailed in the 1950 documentary, "The Hollywood Ten." For them, and the many others put on the blacklist, it would be impossible to find employment in Hollywood or to have a film distributed.

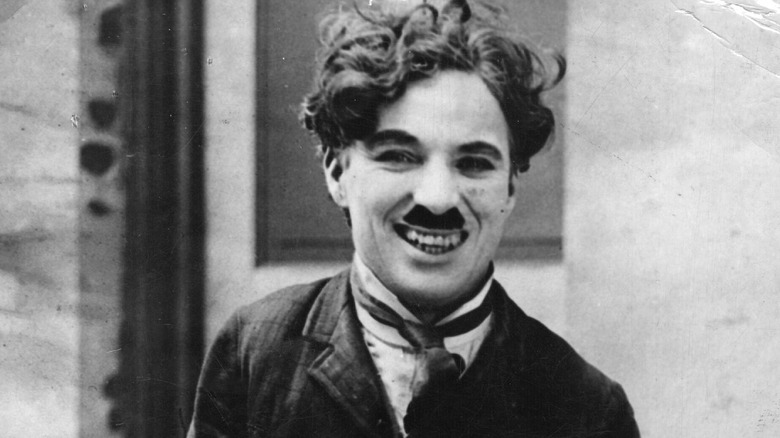

Director, producer, composer, and actor Charlie Chaplin, best known for playing the lovable tramp, was undoubtedly one of the most influential people in film. An article in Rob Wagner's Script, is quoted as stating, "There are men and women in far corners of the world who never have heard of Jesus Christ; yet they know and love Charlie Chaplin."

Far from protecting him, his influence and popularity drew the attention of the FBI. Their investigation would ultimately drive the beloved director not just out of Hollywood, but out of the United States.

The Red Scare, Un-American Activities, and the Rise of Corporate Hollywood

The impact of Red Scare hysteria over communist influence in film can be seen as early as 1919, according to Peter Feuerherd in Jstor Daily. By the '30s, the infamous Production Code was enforcing rules regarding "subversive content" and even going so far as to force some films to be canceled altogether.

When the Cold War began, HUAC turned its attention to Hollywood in earnest, encouraging the production of films that were explicitly anti-communist. While these films weren't particularly successful, some like film scholar Jon Lewis have argued that blacklisting was a way for "studios to regain control over the entertainment marketplace."

HUAC's investigation into the possible communist sympathies of those working in film was actually beneficial to corporate interests. One of the reasons for this was the committee's tendency to conflate communism with Jewishness. HUAC believed that communist Jews in Hollywood were attempting to insert propaganda into films in a way that was undetectable but would still somehow change the opinions of the viewer. While films created by Jewish filmmakers couldn't be simply banned because of the ethnicity or religion of the producer, the blacklist allowed them to be banned for political reasons.

It was effective. By the 1950s, the power of Jewish entrepreneurs and unions had both been weakened, and corporate interests were able to dominate film.

Why was Charlie Chaplin on their radar?

Charlie Chaplin may seem like an unlikely target for an FBI investigation, but their definition of "un-American activities" was extremely broad. As explained in John Sbardellati and Tony Shaw's "Booting a Tramp: Charlie Chaplin, the FBI, and the Construction of the Subversive Image in Red Scare America," Chaplin's status as a cultural icon made the FBI view him as a threat to national security. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had a personal interest in Chaplin and was already collecting information on him in 1922.

While Chaplin was never a communist, he was revolutionary and subversive in many ways, and prevalent anti-communist paranoia mingled with other prejudices. One consistent cause for suspicion was Chaplin's choice to never become a U.S. citizen. Another was his personal life. During the Cold War, it was common for individuals within the government who were perceived as homosexual to be persecuted, but Chaplin's public and controversial sex life is an example of a heterosexual who violated cultural norms enough to arouse federal suspicion.

While some of Chaplin's films were considered communist propaganda, and the FBI maintained that he had communist associations, it was primarily "grave moral charges" that would temporarily turn the American public against him and result in Hoover ensuring that Chaplin would be kept out of Hollywood — and the United States.

Citizenship and the Mysterious Israel Thornstein

While Charlie Chaplin worked and lived in the U.S. for decades, he was a British citizen. According to the Guardian's report on files only released in 2012, the FBI went to MI5 (the United Kingdom's security and counterintelligence agency) for information on Chaplin. One of their primary questions? Chaplin's real name.

The FBI asked MI5 to follow up on rumors that Chaplin was really named "Israel Thornstein" and might have been born in France rather than the U.K. MI5 found no evidence of either. Interestingly, they also found no trace of Chaplin in the U.K.'s birth records and concluded that he must have at one point had a different name or have been born elsewhere.

MI5 officers also speculated Chaplin might be Jewish. According to film historian Matthew Sweet (via Tulsa World), they weren't the first to assume this. Many fans believed Chaplin was Jewish, and he himself didn't attempt to set the record straight. Considering six out of the blacklisted "Hollywood Ten" were Jewish, notes The Jewish Chronicle, antisemitism may well have contributed to the FBI's perception of Chaplin as a threat to American culture.

MI5 continued to tail Chaplin for years and took until 1958 to conclude he was not a threat. Eventually, the agency concluded that while he might be a communist sympathizer, "he would appear to be no more than a 'progressive' or radical."

Influence Upon the Minds and Culture

During the Red Scare, the FBI approached the existence of people working in Hollywood with leftist politics as part of a master plan to produce propaganda that would make the American people sympathetic to the Soviet cause. For them, this possibility was a matter of national security. As quoted in "The US Government, Citizen Groups and the Cold War: The State-Private Network," by Tony Shaw, J. Edgar Hoover himself stated that the film industry was "one of the greatest, if not the very greatest, influence upon the minds and culture."

Not only were Charlie Chaplin movies incredibly popular and influential both in the U.S. and internationally, he was an independent filmmaker and producer. To the FBI, he appeared to be in a prime position to create propaganda films that could pose a threat to democracy. Because of this, and the concerns over the perceived "master plan" at work in Hollywood, the vast majority of Chaplin's extensive FBI file is dedicated to attempts to connect him to individuals that were confirmed radicals and Communist Party members.

How the FBI Gathered Intel on Charlie Chaplin

The FBI utilized methods — some reliable and others highly questionable — to keep informed about everything that Charlie Chaplin did. David Robinson, one of Chaplin's biographers and the man responsible for using the Freedom of Information Act to request Chaplin's FBI file, told the New York Times that he was astonished by "the degree of sloppiness and stupidity that many of the reports reveal."

One method of gaining information was discrete recording. Following a public scandal with the young actress Joan Barry, the FBI took to bugging Chaplin's hotel rooms so they could keep up-to-date on his sex life.

When it wasn't possible to listen to Chaplin directly, they relied on shakier sources — including gossip columnists. Agents went to them to find new leads and even fed them information that they thought it would be useful to have spread through Hollywood. A note on one such interaction in the file reads, "to be destroyed after action is taken and not sent to the files."

The bizarre contents of Chaplin's FBI files didn't end with his death, and neither did the unconventional methods of investigating him. In 1978, Chaplin's body was stolen from its grave. The FBI consulted a clairvoyant. She gave what she believed to be physical descriptions of the perpetrators, the name of one, and a vague location of the body. Unfortunately, she was wrong on all counts (but the body was recovered anyway.)

Blacklists and Informants

What J. Edgar Hoover was really looking for was something to connect Charlie Chaplin to the Communist Party — an eyewitness to testify against him. None existed.

Instead, they had to rely on a network of informants within Hollywood to report those who they felt were working to promote communism. The majority of the redacted portions of the files are held back to protect the identities of these informants. Some names of Hollywood informants have been released, including Ronald Reagan, as detailed by the Chicago Tribune, but for the most part it is impossible to know who was feeding information to the FBI, even today.

According to John Sbardellati and Tony Shaw, many of the informants were unreliable. One who provided information about Chaplin reported that her intel had been overheard in a beauty shop.

When HUAC held hearings, some of the witnesses they called on were willing to "name names" and put others in the industry on the blacklist. According to The Hollywood Reporter, these types of friendly witness informants added over 300 names. One of these friendly witnesses was director Elia Kazan. One of his most famous films, "On the Waterfront," can be viewed as a defense of his actions, as the protagonist is portrayed as justified in "snitching" on his colleagues, notes the Los Angeles Times.

Charlie Chaplin's Actual Politics

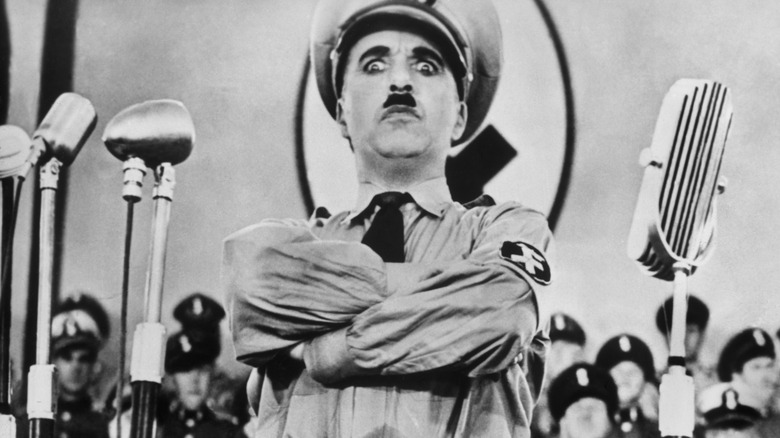

Charlie Chaplin's work was often perceived as friendly to communism, both in the U.S. and in the USSR itself due to its depictions of working class people, such as his film "Modern Times," which features The Tramp struggling against modern industrialization. "The Great Dictator," in which Chaplin satirizes Hitler, clearly marks him at the very least as opposed to fascism.

As Charles J. Maland states in "A documentary note on Charlie Chaplin's politics," Chaplin didn't make public statements about his political views very often, though he openly admired Franklin D. Roosevelt. When he was young, he was friendly with socialists and labor activists, which was enough for the FBI to suspect him. Chaplin himself was not a communist, however. In the few times he ever actually talked about communism, he never expressed more than a passing interest.

"I am an artist. I am interested in life. Bolshevism is a new phase of life. I must be interested in it," Chaplin is quoted as telling a reporter in Maland's book. When pressed, he went on to say he was "not a politician."

Who was Joan Berry?

Charlie Chaplin met an actress in L.A. named Joan Barry. According to Mental Floss, he was considering her for a role in an upcoming picture. The FBI was documenting every move that Chaplin made, and his file states that he invited her to New York City and paid for her train ticket. This decision would have devastating consequences for Chaplin.

Their relationship was brief and volatile. Only two months after the two were spotted partying together in Manhattan, Barry broke into Chaplin's home with a gun. She would go on to have a child that she claimed was conceived around that time. She told Chaplin he was the father. When Chaplin denied it, she took him to court.

Barry took Chaplin to court for violating the alarmingly titled "White Slave Traffic Act," better known today as the Mann Act. The charge was that when he brought her to New York, he had moved her across state lines for "immoral purposes." Though Chaplin was indicted, he was eventually exonerated. Then Barry brought Chaplin back to court for paternity.

Blood tests (the only method available at the time for verifying paternity) concluded that Chaplin was not the father, but Barry refused to drop the charges. Two trials followed — and blood tests were not considered admissible evidence. The first jury was unable to reach a decision, but the second decided that Chaplin was the father. Chaplin was forced to pay child support, and the public scandal permanently damaged his reputation.

Charlie Chaplin's Love Life – a Complex Legacy

Even without the affair with Joan Barry, Charlie Chaplin's love life was controversial – and it remains so today.

Sen. William Langer is quoted by John Sbardellati and Tony Shaw as calling for Chaplin's deportation on the grounds that he had "an unsavory record of lawbreaking, of rape, or the debauching of American girls 16 and 17 years of age."

It can be difficult for a modern reader of Chaplin's FBI files to determine what is factual, considering so many of the sources of information were unreliable, and Chaplin was being targeted for xenaphobic reasons with the intent to damage his reputation and ability to release films. While the moral concerns raised by the FBI investigation may have been used as a way to deport a man who they saw as a political threat, that doesn't mean that what was uncovered can be dismissed as propaganda.

While Langer was likely more interested in deporting Chaplin due to politics, it is completely true that Chaplin had romantic relationships with teenagers. Chaplin's first wife, Mildred Harris, was only 16 years old when they married. His second wife, Lita Grey, was also 16. While his third wife, Paulette Goddard, was 22 when they met, Biography reports that she told Chaplin she was 17. He was in his 50s when he met his fourth and final wife, Oona O'Neill. She was 18 years old.

The Charges against Charlie Chaplin

Chaplin was officially denounced by The House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947. Chaplin had worked hard for years to avoid scandal and the risk of prosecution. According to Richard Brody's article in the New Yorker, "Charlie Chaplin's Scandalous Life and Boundless Artistry," he even paid a doctor $25,000 to change the date on the birth certificate of one of his children.

Once he was among the most popular people in America, but between the denouncement and his public scandals in the press, the public turned on him. His new film, "Monsieur Verdoux," bombed at the box office and was critically panned. Reporters at Chaplin's press conference for the film confronted him with questions about his choice not to become an American citizen and even went as far as to ask him to name his friend, composer Hanns Eisler, to the press as a communist.

"I don't know anything about that. I don't know whether he is a Communist or not. I know he is a fine artist and a great musician and a very sympathetic friend," said Chaplin during a press conference. He went on to say it wouldn't make a difference to him if Eisler was a communist (via John Sbardellati and Tony Shaw).

Banned from the U.S.

Charlie Chaplin's next film after "Monsieur Verdoux" was called "Limelight," and it has often been interpreted as commentary on Chaplin's changing position in Hollywood and the public eye. The New Yorker quoted "Limelight" actor Norman Lloyd's understanding of the film as "Chaplin's way of saying, 'I, Charlie Chaplin, doubt that I can make people laugh any longer.'"

Chaplin traveled to London for the premiere of 'Limelight," with the intention of going on a European tour to promote the new film. As detailed in "Booting a Tramp: Charlie Chaplin, the FBI, and the Construction of the Subversive Image in Red Scare America," J. Edgar Hoover advised the attorney general to revoke Chaplin's reentry permit due to "grave moral charges" and allegations of communist offenses.

If Chaplin wanted to return to the United States, which had been where he had lived and worked for decades, he would have had to apply for entry again. Doing so would force him to answer many official questions about his personal life, from his morals, to his sexual behavior, to the political views of him and his friends.

After years of trying to protect his reputation in Hollywood, Chaplin gave up on the possibility of making films in the U.S. He and his family moved to Switzerland. Chaplin said that he would never return.

A King in New York, in England

While Charlie Chaplin couldn't come back to Hollywood, he continued to work. In 1957, his film, "A King in New York," was released in England. It wasn't shown in the United States. After the protests at "Limelight," moviegoers in America were still considered too hostile to Chaplin.

Since most Americans hadn't seen the film, many speculated that Chaplin had become bitter and created an anti-American picture. But in reality, "A King in New York" is a nuanced satire with commentary on Hollywood, the House Un-American Activities Committee, and American society. Film critic Roger Ebert, reviewing the film in 1972, noted that the protagonist played by Chaplin, "meets a young boy (Michael Chaplin) whose parents have been asked by HUAC to rat on their friends," and that later, "There's some satire of a congressional investigation into communism, but Chaplin doesn't hit too hard and finally plays it for laughs (he gets his finger stuck in a firehose nozzle and inadvertently drenches the committee.)."

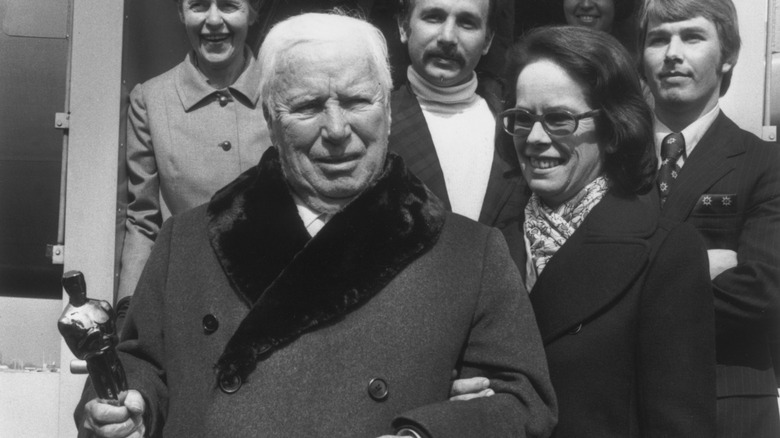

Although Chaplin had sworn never to return to the United States, he did come back once — for the 1972 Oscars, where he received an honorary award. He was greeted by a standing ovation and cheers that lasted until he finally had to quiet the crowd himself.