The Truth About George Washington's Teeth

According to Atlas Obscura (posted on YouTube), by the time George Washington was inaugurated as the first President of the United States on April 30, 1789, he had just one working tooth left in his head. The 57-year-old had suffered a lifetime of dental problems that caused him great pain and made it difficult to eat. Dating back to his early 20s, Washington made reference in his letters and diaries to toothaches, teeth he had pulled, dentures that didn't fit, inflamed gums, and a whole litany of other dental disasters. Washington also recorded his many payments to dentists, as well as expenses that included toothbrushes, teeth scrapers, medication, and denture files.

One of the two enduring myths about George Washington was that he had wooden teeth (the other being the cherry tree legend), but while the founding father had several sets of dentures throughout his life, none were made of wood. Washington's dentures may have been stained to the point of appearing as wood to those around him, but they were quite advanced at the time, though that isn't saying much. They were made of many materials, including teeth he bought from poor and enslaved people, horse and cow teeth, lead, ivory, copper, and silver, according to Mental Floss. He also kept many of the teeth from his own tooth loss over the years so that they could be used in his dentures, and locked them in his desk drawer at Mount Vernon so they would remain safe and out of view.

Washington's teeth had a role in the Revolutionary War

During the Revolutionary War, George Washington may have been focused on his duties, but his nagging dental woes didn't disappear. In 1781, he learned that a prominent French dentist by the name of Dr. Jean-Pierre Le Mayeur, who had been providing dental services to the British officers, had escaped British occupied New York City to serve the American cause. Washington quickly found and enlisted the services of Le Mayeur, per The Conversation. It could have been a disaster if Le Mayeur had been operating as a spy for the British, but Washington made Le Mayeur part of his inner circle and invited him to Mount Vernon. Le Mayeur wrote in a 1784 letter (via the National Archives), "I shall always remember with singular pleasure and Gratitude the marks of a kind and generous regards which have been Evident in the attentions I have had the honor of Experiencing from your Excellency and Lady Washington."

Washington's dental troubles also threw the British off-balance when they intercepted a letter from Washington requesting dental tools be sent to him outside New York, leading the commander of the British forces to fortify camps up north, according to George Washington's Mount Vernon. What the British didn't know was that Washington and the French had just planned a military operation in Virginia that would become known as the Siege of Yorktown of 1781, leading to the surrender of more than 7,000 British troops.

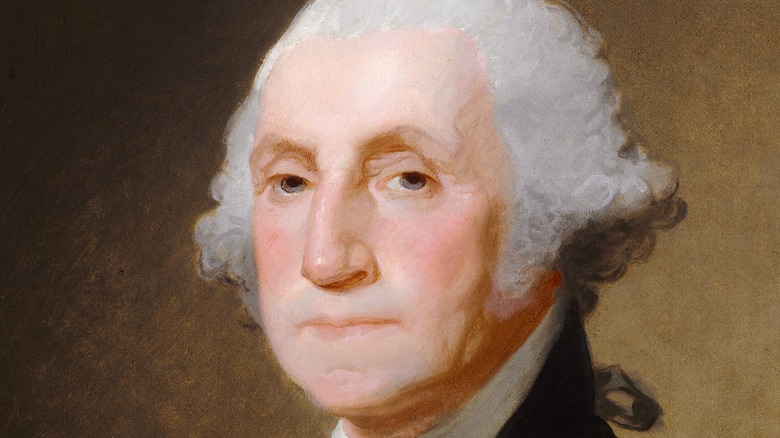

Washington's dentures changed the shape of his face

Throughout his dental woes over the years, Washington had several pairs of dentures. None of them fit properly and they often caused swelling, making it difficult to talk and eat. The dentures also changed Washington's very appearance. Artists and other close observers took notice of the striking changes the dentures made in the shape of his face. A progression of paintings over the course of his life appear to depict the sometimes radical changes, particularly in the shape of his jaw and his mouth, according to Pop Science.

It was a change that Washington appeared to be well aware of. In a 1797 letter to one of Washington's long-serving dentists, Dr. John Greenwood, he wrote (via the National Archives) that the dentures were "already too wide, and too projecting for the parts they rest upon; which causes both upper, and under lip to bulge out, as if swelled." He followed up the next year, noting that a more recent set of dentures had "the effect of forcing the lip out just under the nose." Ironically, what many consider to be the iconic, stoic face in portraits — of a military commander who led the Patriot forces to victory in the Revolutionary War, who went on to become the steadfast first President of the United States — some of that steely resolve is really just the result of bad dentures.