George Washington's Tragic Death Explained

Every American knows about George Washington's life, from the myth that he once chopped down a cherry tree to his role as the military leader who secured America's freedom and then served as its first president. Washington had plenty of flaws, but there's no arguing against his importance in American history.

Washington led a poorly-supplied and often undisciplined fighting force against one of the greatest and best-trained professional armies in the world, ultimately pulling off one of the greatest upsets in military history. Then, as a war hero and unstoppable political force, he refused to leverage his influence into permanent power, setting the tone for the peaceful transfer of power that has defined the United States ever since.

In many ways, George Washington is the most influential American to ever live. Which makes it surprising that so few Americans know the details of his death, which by all accounts, was a remarkable one. Washington didn't die in battle, wrapped in glory. He didn't die peacefully, in his bed. On the contrary, George Washington died in extreme pain, quite suddenly — and possibly unnecessarily — in 1799, only a few years after he left office. If you want George Washington's tragic death explained, you'll hear a story that will make you very grateful for modern medicine.

Death denied George Washington his retirement

No one was more prepared for a long and peaceful retirement than George Washington. When his second term as president ended in 1797, he was 65 years old and had been serving his country for more than 20 years. He'd planned to retire a decade earlier, as History.com reports, writing in 1787 that "It shall be my part to hope for the best . . . to see this country happy whilst I am gliding down the stream of life in tranquil retirement." He never got that peaceful retirement.

That initial plan was ruined when the Articles of Confederation were replaced with the Constitution and he was elected the first President of the United States in 1789. Washington took his responsibilities very seriously and felt he couldn't turn down the job, and so delayed his retirement for another eight years.

When he finally managed to step away from service, he had to work to manage his large estate, which was comprised of five working farms, 123 horses, mules and asses, 680 cattle and sheep — and about 300 enslaved workers. According to CBS News, George Washington was still involved in the country's affairs, and when he was asked to serve as Commander-in-Chief of the army in 1798 as tensions grew with France, he accepted — though his services were not needed in the end. When he passed away a little more than a year later, he'd barely had any time at all to enjoy his "tranquil retirement."

George Washington's retirement killed him

The most tragic aspect of George Washington's death is that his retirement literally killed him. If he hadn't retired, he might have lived a much longer life.

As History notes, Washington's brief retirement was marked by two main activities: Managing his estate at Mount Vernon, and entertaining an endless procession of guests. Washington's estate was comprised of five working farms that took a lot of work to keep going. Of course, Washington didn't do all the work himself — as The Washington Post reports, our first president was, in fact, a slave owner. While Washington was questioning the institution of slavery near the end of his life, about 300 enslaved workers ran his farms until his death.

Washington spent most of his days riding around his estate to ensure that repairs were made and crops were tended. When he got home, he almost always had guests for dinner. In 1798 alone he received almost 700 guests. Some of these were friends, while some were strangers who came to pay their respects. Washington took his role as host seriously, however.

On December 12, 1799, George Washington spent the day riding around in snow and sleet and returned home later than usual, soaking wet. His guests had already arrived, so he decided not to change out of his wet clothes and sat down to dinner. The next day, Washington woke up with a sore throat, the start of the final illness that killed him the following day.

Washington's illness moved fast

We've all experienced waking up with a sore throat, a sure sign that we're about to get sick. It's almost always a mild illness — and in the rare cases where it signals something worse, we can usually expect to have several days of worsening symptoms.

For George Washington, however, it was a different experience. As PBS NewsHour reports, he woke up with a sore throat on December 13, and he was dead a little more than a day later.

The disease, which modern doctors believe was probably acute bacterial epiglottitis, moved with terrible swiftness. After going out and doing his work to run his estate on December 13, Washington awoke in the middle of the night, struggling to breathe. As Smithsonian Magazine notes, he had chills and fever, and his throat had become swollen. Doctors attended the former president all day, but his condition continued to get worse and worse (in part due to the crude treatments his doctors inflicted on him).

At five o'clock in the evening, Washington rallied slightly and was able to review his last will and testament and issue some instructions about his burial and his business. About five hours later, he fell unconscious and died on December 14, 1799. Washington's entire illness lasted less than two days.

George Washington was basically bled to death

George Washington's illness — most likely acute bacterial epiglottitis — was pretty bad. As Smithsonian Magazine notes, before the age of antibiotics, most people would die from the disease. So despite the fact that Washington had no fewer than three doctors working to keep him alive, it's not surprising that they failed. But the tragic truth is that the disease barely had a chance to kill Washington because his doctors were quickly bleeding him to death.

Bloodletting was still considered a perfectly rational practice in late 18th-century medicine, though it was in decline. As National Geographic reports, the idea that reducing the amount of blood in the body would relieve all manner of symptoms is an idea that has persisted for centuries and was listed in a medical textbook as recently as 1942.

So it's not crazy that George Washington's doctors would decide to bleed him. What is a little crazy is just how much blood they took. According to PBS NewsHour, the three doctors, led by George Rawlins, eventually took 80 ounces of Washington's blood, an astounding 40% of his total blood volume. The blood loss would have been compounded by the associated dehydration and electrolyte imbalances, inhibiting any chance that his body could fight off the infection. In other words, George Washington was essentially bled to death by his own doctors.

Washington's treatment was torture

George Washington was the most prominent citizen in the young country in 1799 and a wealthy man to boot. He could afford the best in medical treatment and had no less than three doctors treating him as he battled his final illness. While most modern doctors concede that without antibiotics Washington's chances of survival were slim, the 18th-century treatments applied to Washington were not just ineffective — they were agonizingly painful.

As Dr. Marc Barton notes on Past Medical History, first they bled Washington, taking nearly 40% of his blood. This was not only ineffective, it was dangerous, leaving Washington weakened and on the brink of hypovolaemic shock. Next, they applied a "blistering agent" to his throat. The theory was that the infection that was causing his throat to swell had to be drawn out, and a chemical burn that caused blisters would draw it out of his body. All this did, however, was make Washington's throat worse.

Trying to soothe his blistered throat, Colonel Tobias Lear, Washington's chief aide, fed him a mixture of butter, molasses, and vinegar. This backfired, as Washington began to choke on the stuff. Finally, the doctors induced vomiting and applied an enema. These procedures in combination with his blood loss left Washington dehydrated and weak, so naturally, the doctors bled him one final time.

Washington faced death bravely

George Washington was a human being, as flawed as anyone. But you could never accuse him of cowardice. After repeatedly demonstrating his bravery when facing both bullets and opposing politicians, Washington had one last opportunity to prove his bravery — and he did not disappoint.

First, when Washington began to feel very unwell, his wife, Martha, suggested she go to fetch a doctor. According to The Washington Library, the former First Lady had just recovered from an illness herself, and Washington wouldn't let her go out into the cold to do so. After feeling worse and worse over the course of hours and enduring painful treatments, Washington was all business. He reviewed his will and calmly issued instructions for his burial.

Later, as author Frank E. Grizzard notes, Washington called his personal physician and old friend James Craik over to him and said, "Doctor, I die hard; but I am not afraid to go; I believed from my first attack that I should not survive it; my breath can not last long." After facing death as calmly as anyone possibly could, Washington took the time — while dying — to thank the three physicians who had tried so hard to save him, proving that not even death could strip Washington of proper etiquette.

Washington settled accounts

When in the grip of a deadly illness, most people are laser-focused on their own suffering and survival. George Washington was in incredible pain from both his illness and the treatments, but he was also aware of his legacy and the impact his death would have on the people he loved. Just hours from death, Washington summoned the energy and presence of mind to get his affairs in order and ensure that his death would be handled as he saw fit.

Washington was a leader to the end and refused to leave a mess behind him. He reviewed his last will and testament and made certain that Martha Washington had the correct version in her hands. According to The Washington Library, he then called his private secretary, Tobias Lear, into the room and told him, "I find I am going, my breath can not last long. I believed from the first that the disorder would prove fatal." Washington then gave Lear instructions concerning his personal papers, bills that needed to be paid, his burial, and his final correspondence. He only had a few hours to live. George Washington used his time to finish his business, calm and cool until the end.

George Washington worried about being buried alive

The fear of being buried alive wasn't entirely crazy before the advent of modern medical technologies like the electrocardiogram as History.com reports. It's actually not always easy to determine if someone is actually dead and not in a deep coma, with extremely faint respiration. And history is actually filled with horrifying stories of people who were buried alive — Smithsonian Magazine notes that the fear was so common, "safety coffins" were invented so people could ring a bell if they woke up and found they'd been buried.

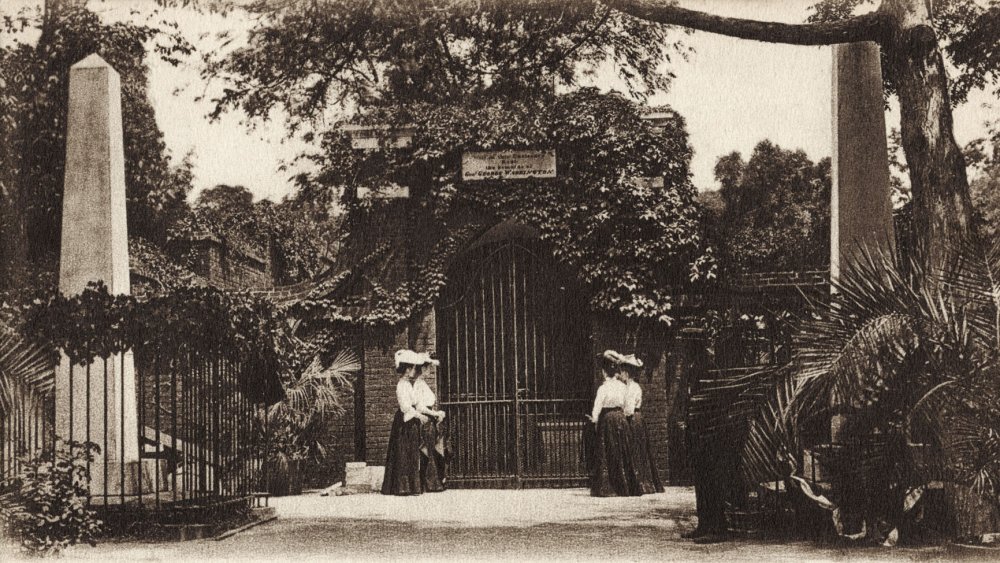

George Washington faced the battlefield and his own death bravely, but he was worried about the possibility. As author Sarah Murray writes, on the night of his death Washington asked that his burial be delayed in case he suddenly recovered. He instructed his secretary, Tobias Lear, "Have me decently buried; and do not let my body be put into the vault in less than three days after I am dead." As The Washington Library notes, our first president even demanded that Lear confirm that he understood the instruction.

When Lear indicated that he understood, Washington relaxed, confident that he wouldn't have to worry about the horror of being buried alive. He uttered his final words before passing away a few hours later: "'Tis well."

There was a plan to bring Washington back from the dead

The plan William Thornton came up with when he arrived at Mount Vernon shortly after George Washington's death was ... pretty insane.

Thornton was a family friend of Washington's, a prominent physician, and an architect. He had a fascination with the inner workings of the body. As i09.com reports, Thornton arrived too late to bid goodbye to the great man, but he had an idea: He would resuscitate him back from the dead.

As The Washington Papers notes, Thornton was extremely saddened by Washington's death, describing himself as "overwhelmed" by the loss of his "best friend." So his emotional reaction is understandable. When he observed that Washington's body had become frozen after sitting in the cold for several hours, he recalled scientific research about animals recovering after being frozen. Thorton thought it was possible he might be able to do the same for Washington.

William Thornton's plan involved several stages. First, he wanted to heat up George Washington's body by placing him near the fire and rubbing him with blankets. Then he would perform a tracheotomy (cutting a hole in the throat), insert a bellows, and inflate his lungs with air. Finally, he planned a full blood transfusion — using lamb's blood. Luckily, Martha Washington refused this offer, believing that Washington had earned the peace of eternal rest — something Thornton himself later came to agree with.

George Washington had two wills

George Washington was a capable and accomplished man who had served as both the commander-in-chief of the army and as our first president. Needless to say, he was a talented and capable administrator and a man who understood the importance of being organized.

So it's not terribly surprising that Washington prepared his will long before his death. What's a little surprising? Washington actually prepared two different wills a few months before he died.

We'll never know what was in the second one, because as Smithsonian Magazine reports, a few hours before taking his final breath, Washington asked his wife to bring both to him. He reviewed them, then tossed one into the fire and presenting the other to Martha for safekeeping. We do know that in the version that survived — which The Washington Library notes was written by Washington himself, on his own watermarked stationery — Washington was determined to free the people that he enslaved. As History.com reports, his will specified that the enslaved workers should be legally freed, and instructed that they "shall be comfortably clothed and fed by my heirs while they live."

The legalities surrounding Washington's enslaved workers were complex, though. Only one enslaved man, William Lee, was immediately set free when Washington died. It took about a year for Martha Washington to emancipate the rest.

Washington was considered an old man

The death of George Washington was a shock to everyone, but what was most surprising to people at the time wasn't the fact that he'd died, but rather the rapid progression of his illness within a day. Washington was 67 when he died, which most people at the time considered to be very, very old.

Today, 67 is the retirement age. Anyone reaching that age in reasonable health would expect to have many years, perhaps decades left to live. But as The Morning Call notes, in the late 18th century, the average life expectancy for a man was just 38 years old. When George Washington stepped down from his second term as president at the age of 65, he was already considered to be an unusually old man.

Washington himself never expected to live that long. As History reports, most of his male relatives, including his father, had died before the age of 50. Washington assumed this was his fate as well. When the Revolutionary War ended in 1783, Washington was 51 years old and fully expected to retire. Of course, he never got the chance, as the country's new government need a president in 1789. Washington once again stepped forward to serve.

It took four days for Congress to hear about George Washington's death

You might assume that news of George Washington's death raced around the country, prompting Congress to immediately commission the Washington Monument. But the technology of the time meant it took a lot longer for news to spread — and the Washington Monument was already in the planning stages.

According to NBC12, Congress didn't hear about Washington's death until December 18, four days after he'd passed. The news had to be brought in person, after all; there was no long-range communication technology in those days, not even a telegraph. And Congress had no reason to worry about Washington. Although he was very old for the time at 67, he was in good health and very active, so his death was an incredible shock.

Surprisingly, the Washington Monument wasn't inspired by the great man's death. The monument had first been proposed in 1783 as the Revolutionary War ended, per History.com. Washington himself ended the project when he became president in 1789, noting that the young country was strapped with debt and needed every dollar it could scrounge.

After George Washington's death, you might imagine the renewed push for a monument means it was built very quickly, but you would be wrong again. It took more than 50 years for the iconic obelisk to finally be started. It wasn't finished until 1884 and wasn't dedicated until 1888 — nearly a century after Washington's death.