The Untold Truth Of Fats Domino

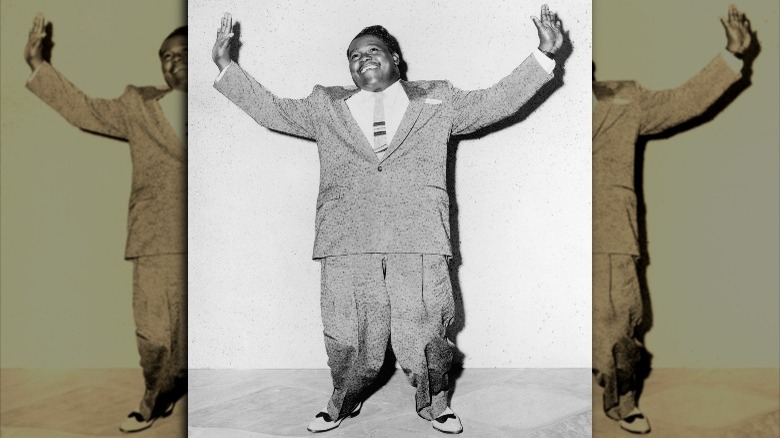

Back in the days before Auto-Tune, musicians had to have raw talent: And Fats Domino was practically brimming with it. Born Antoine Dominique Domino Jr. in New Orleans on February 26, 1928, the man everyone knew as Fats would grow up to become one of the earliest and most beloved pioneers in a brand-new genre that had all the kids dancing and all the parents wondering what that heck was going to become of this new generation. That was, of course, rock 'n roll.

Domino, says The New York Times, taught himself to play mainly by just listening to — and then replicating — the style and songs of the jazz and boogie-woogie greats of the era. And then? He made it his own. As a teenager, he worked with the nightclub band of bassist Billy Diamond, who explained Domino like this: "When you saw Fats Domino, it was, 'Let's have a party!" ... He was a great singer. He was a great artist. And whatever he was doing, nobody could beat him."

So, what don't you know about this founder of rock 'n roll?

Fats Domino was the grandson of slaves and the son of sharecroppers

To put things in perspective, Fats Domino was born only 65 years after the end of the Civil War, and the Emancipation Proclamation. It's not entirely surprising, then, that his father came from a family of Haitians who had first set foot in America as slaves. When they were freed, they continued to live in Louisiana — and Acadiana Profile says that Domino's parents were sharecroppers, working on property that had belonged to the Laura Plantation.

Domino grew up in New Orleans' Lower Ninth Ward, and says it was an area that not only shaped his childhood, but his adulthood, too — unlike many stars that hit it big, he lived in his hometown for much of his life. The Atlantic describes the area as "mostly rural, with unpaved streets, farm animals, and scarce electricity and indoor plumbing."

It's arguable that had he been born anywhere else under any other circumstances, modern music might have looked very different. The combination of Creole influences, Haitian history, a heavy, French-influenced regional accent, and the blues scene of the city all wrapped around his raw talent to kick off a career that changed the course of American music.

He taught himself how to play

Sometimes, it's impossible for parents to tell what's going to create that spark in their child, and in Fats Domino's case, it was a piano that his family inherited. He was 10 years old when the instrument was moved into their home, and then? He was so captivated by it that his parents then decided it needed to be moved to the garage.

According to The New York Times, Domino's first great influence came in the form of his brother-in-law. Harrison Verrett was a jazz musician, and gave him the groundwork of explaining things like notes and chords. From there onwards, it was all Domino. It turned out that he had an almost supernatural talent: after listening to a record just a handful of times, he could flawlessly replicate it. He modestly said in one of his rare interviews that he "had a good ear for catchin' notes and different things," and everything the world would later love in songs like "Blueberry Hill" was entirely self-taught.

Domino dropped out of school in the fourth grade, and — like so many of his generation did — went right to work. He got a job as an assistant iceman, delivering ice to homes across the city. Still, the music called: "In the houses where people had a piano in their rooms, I'd stop and play. That's how I practiced."

Why 'Fats'?

There's a few different stories about how Fats Domino got his nickname, and it ultimately led to his breakout hit. In 1949, he was signed to a record contract, and that's when he and longtime songwriting partner David Bartholomew wrote "The Fat Man" — which sold more than a million copies within just a few years (via The New York Times).

But Domino was already "Fats," a nickname that The New Yorker says came from bassist and band leader Billy Diamond. It wasn't a comment on the 19-year-old prodigy's size at all: It was a nod to two jazz pianists Domino reminded him of, named Fats Waller and Fats Pichon.

After the release of "The Fat Man" and lyrics like, "They call me the Fat Man/'Cause I weigh 200 pounds," it absolutely became linked to his size. Domino, says Forbes, embraced it. Standing just 5'5", he was fond of saying that he was as wide as he was tall. As an interesting footnote, The Philadelphia Inquirer says that when a man named Ernest sang "The Twist" for Dick Clark and his wife — then did a spot-on Fats Domino impression — she decided on a similar weight-board game name for him, and he became Chubby Checker.

Fats Domino's music was absolutely ground-breaking

While Fats Domino might not have the same sort of name recognition today as someone like Elvis Presley, it's impossible to stress just how important he was to shaping the genre as a whole. Even Presley said in a 1957 interview (via The New York Times): "A lot of people seem to think I started this business. But rock 'n roll was here a long time before I came along. ... Let's face it: I can't sing it like Fats Domino can. I know that."

Presley pointed him out as "the real king of rock 'n roll," and that's legit. According to American Blues Scene, Fats Domino was the first rock musician who was marketed as a pure musician. He broke out of the gimmick, novelty songs that had come before him, and fans knew they were listening to something special right from the beginning. With record sales of more than 65 million, Domino outsold everyone — save for Elvis.

He's also credited for recording the very first rock album. Questions about what defines the genre means that's always going to be up for debate, but according to The Guardian, the first belonged to Domino. Interestingly, the first song he ever recorded pre-dates that record — the first song was actually a traditional song to the voodoo god of luck, and it was called "Hey La Bas."

Fats Domino is credited with going a long way in desegregation of rock 'n roll

When Fats Domino was in his heyday, the U.S. was still mostly segregated, and Jim Crow laws were still a thing. Rick Coleman — who wrote "Fats Domino and the Lost Dawn of Rock 'n' Roll" — says (via The Guardian) that Domino was one of first and most important artists who kicked down the very physical barrier between Black and white.

Domino's concerts became notorious for integrating audiences: Take his May 4, 1956 show in Roanoke, Virginia. Brian Ward, Northumbria University's professor in American studies, says (via The Conversation) the concert was originally segregated: Black fans on the dance floor, and white fans in the balcony, which was crammed to about double capacity. When white fans started heading down to the floor, less accepting fans started hurling beer bottles at those dancing below.

Integration — a highly controversial phenomenon at the time — became a common sight at Domino's concerts as Black and white fans tore down ropes and barriers to dance together, and the subsequent fights that broke out were often deemed race riots. PBS, however, says that wasn't the case at all, and problems only started when people who didn't like the idea of fans breaking segregation laws called law enforcement, who then used things like tear gas to try to break up the party. It didn't work, and Domino continued to play integrated concerts, and have major hits with Black and white listeners alike.

Dealing with racism in 1960s America

As the face of this new and controversial kind of music, Fats Domino answered some serious questions. After a riot broke out at one of his concerts on a Rhode Island naval base, he was asked if the music was to blame. PBS says he just smiled, shrugged, and said, "Well, know you, when the Navy and the Marines get together..."

He was perfectly aware of the racial tension that swarmed around his performances, and around this new genre. According to The Conversation, there were no shortage of incidents like the one following a 1956 concert in Virginia. After the show, a white mob congregated and chased Domino and his band to their hotel... in the Black section of Roanoke. It was the only place they could stay: in spite of their chart-topping popularity, even the era's biggest stars still faced discrimination.

Domino even had a run-in with the KKK, recounted by saxophone player Herbert Hardesty (via NPR). He says he'd been driving their bus through South Carolina when they got lost, and when he came across a group to ask for directions, it was a crowd of Ku Klux Klan members. He explained they were just trying to get back to the highway, and "they were very nice," giving them directions as a cross burned in the background.

The first rock 'n roll riot was at a Fats Domino concert

Rock has always had a bit of a reputation among those who just don't get it... ya follow, daddio? There's good reason for that, and in hindsight, a Fats Domino concert might seem like the most inoffensive venue in the world — but the very first riot happened at his July 7, 1956 show at the Palomar Gardens Ballroom in San Jose.

According to the Los Angeles Times, the concert got off to a rocky start when the band was around two hours late. By the time they finally went on stage, most of the 3,500 people there had already been drinking for a while, but everything was fine when Domino and his band took the stage. But, when they broke for an intermission, it just took one person to throw one beer bottle to kick things off. Overhead lights broke and fights broke out, and it escalated to the point where hundreds broke windows and fled that way, while others made for the emergency exit. Matters only got worse when someone threw some firecrackers into the mix, and by the end of it, 11 people were arrested.

The media ran stories of the "rock 'n roll riot," and while the city briefly considered banning rock music, they rethought that idea and got rid of bottles instead. Still, it kicked off another discussion: What influence does music have on teens?

White artists built their career on him

The Belleville News-Democrat says Pat Boone was one of the biggest stars who built his career covering songs from Black artists — including Fats Domino's "Ain't That a Shame." Both versions were out by 1955, and the story goes that when legendary DJ Alan Freed polled listeners, they said they preferred Boone's version. And it gave Boone a leg to stand on, so to speak, and he went on to make comments like this: "They were thrilled because they wrote the songs. They made more money from my records than they did from their own and it introduced them to a far larger audience that they didn't have any access to at that point."

Was that the truth? Not necessarily. Brian Ward, professor in American studies at Northumbria University, says (via The Conversation) that Domino — along with artists like Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry — had "major hits on both sides of the racial divide." Meanwhile, record companies continued the trend of offering Black artists a flat fee for the rights to a song, then raking in the big bucks by having someone else sing it.

Boone insisted his cover of "Ain't That a Shame" was fine: AP reports that Boone was fond of saying Domino would show off his rings before playing his version, and say, "Pat Boone bought me this ring with this song."

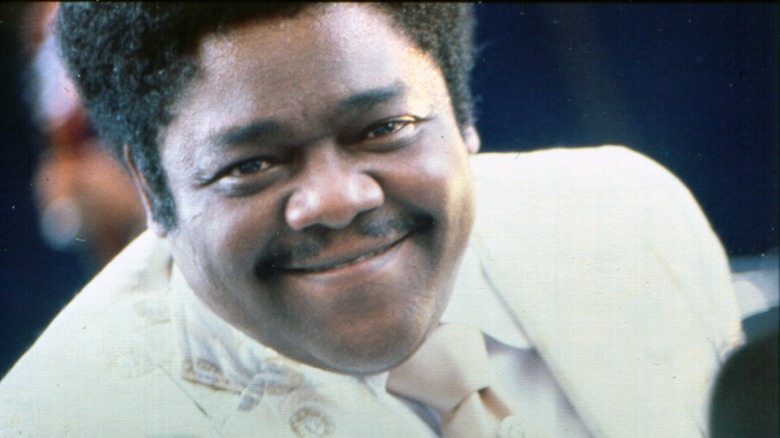

Fats Domino suffered from severe stage fright and anxiety

So here's a question: Why don't we remember Fats Domino like we remember Elvis? Filmmaker Joe Lauro was invited to make a film about Domino, and says (via Rolling Stone), "he was just being forgotten because of his shyness and the fact that he lived a very private, un-crazy life. The man was on the road for 40 years, but he's not ... lighting the piano on fire. He's not marrying his cousin that's 13. ... Of course, his extreme shyness is the reason why he was forgotten." With Domino, there was none of the jail time, none of the controversy. When he wasn't playing music, Lauro says, he was cooking.

Domino's longtime collaborator told NPR that he'd always been "extremely shy," preferring to eat at home, and pop in unannounced to his favorite hometown bars instead of arranging and giving interviews — which he had a tendency to cancel.

NOLA says that it was much more than just shyness. In 2007, Domino was scheduled to play at Tipitina's — but no one knew if he was going to be able to get on stage. The then 79-year-old had been away from performing for a while, and they say it exaggerated the stage fright and anxiety that had been a longtime and constant companion. That night — unlike previous nights — he did get on stage, pushed partially by the fact that it was a benefit concert for his beloved New Orleans' Ninth Ward.

Fats Domino pretty much retired in 1995

Fats Domino had an insanely long career, and in 1986, he — along with Elvis, Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, Sam Cooke, James Brown, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, and the Everly Brothers — became the first group of musicians to be inaugurated into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He was still touring off and on at the time, and his last official tour came in 1995.

That tour, says NOLA, was a pretty bad one: Domino was suffering from a bout of chronic illness and exhaustion as they made their way across Europe. He was in the U.K. for a set of performances — where he was joined by Little Richard and Chuck Berry — when he started to feel very, very sick. He was hospitalized, says the Independent, and warned that "performing live could severely damage his health." The official diagnosis was a "serious infection," but it was likely compounded by the exhaustion of tragedy: Domino had learned just days before of the death of his sister.

Afterwards, he stayed mainly in his New Orleans, even declining a trip to Washington, D.C. to receive the National Medal of Arts in person. Appearances were few and far between, and included — on the rare occasion — private performances, or sets at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival.

Fats Domino lost just about everything in Katrina

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina swept across the Gulf Coast, devastating everything it touched and resulting in a final death toll of 1,833. For a short time, Fats Domino's name was whispered as being among the casualties.

Even after the warnings to evacuate were given, Domino refused to leave his home in the Lower Ninth — partially, says the Independent, because his wife Rosemary was ill, and he didn't want to move her. And partially, they say, "out of stubbornness." Domino was ultimately evacuated, on September 1st — after the water had risen to a depth of 15 feet. After being plucked from his home, he was taken to the Superdome with other refugees. Almost shockingly, his worry about the whole thing was, well... in 2006, he told The New York Times, "I wasn't too nervous. I had my little wine and a couple of beers with me; I'm all right."

In the end, Domino lost everything in the hurricane floodwaters: From his gold records and his memorabilia to his home, it was all gone. Just a year later, he released his first new album in about 10 years. It was called "Alive and Kickin'," a reference to the resilience of the city and his own survival, and part of the proceeds went to help other musicians. And, proving that all possessions can be replaced, President George W. Bush made it a point to visit him in 2006, and replace his National Medal of Arts.

His piano went on a journey of its own

Among the many possessions Fats Domino lost during Hurricane Katrina was his famous white Steinway piano, a showpiece that had stood in his living room and featured heavily in all of his family photographs. It's now at the Louisiana State Museum, but The Atlantic says that getting there meant going a long, long way.

After Katrina, the piano spent weeks submerged in nine feet of water that had overflowed from the Industrial Canal, and restoring it cost a whopping $35,000. Still, it was too damaged to be made playable again, as conservators said replacing all the parts damaged by the floods would result in a whole new piano. Today, it represents something else.

When Lieutenant Governor Jay Dardenne presided over the dedication ceremony in 2013, he said, "[Fats Domino's] beautiful grand piano, fully restored, will serve as the perfect symbol for Louisiana's resilient nature and ever-evolving musical heritage."

I'm Walkin'

Fats Domino left his home on Caffin Avenue during Katrina, but he would ultimately return to live in Louisiana. Just not to New Orleans. In 2006, he still hadn't gone home, and was asked (via The Atlantic) if he was hoping to rebuild his Caffin Avenue house. He said, "I hope so. I like it down there." But he never would.

When Fats Domino died on October 24, 2017, he passed away in his home in Harvey, Louisiana — a stone's throw and a river away from his beloved New Orleans. He was 89 years old, and it was reported that he had died of natural causes.

Through it all, Domino considered himself lucky. In 1985, he told the Los Angeles Times (via The New York Times): "I was lucky enough to write songs that carry a good beat and tell a real story that people could feel was their story, too — something that old people or the kids could both enjoy." And still can.