Ancient Medicine That Did More Harm Than Good

People have been getting ill since the dawn of human history, and they've been searching for medicine to tend to their ailments for just as long. Some cures have lived on for centuries, such as willow bark, which is now an ingredient in aspirin. Other medicines work less effectively than previously thought, or can actively harm the patient. Some medicine even kills. Around the world and throughout history, different cultures have had remedies they swore by for centuries, but in more recent years, as knowledge of medicine has increased, professionals have moved away from or outright abandoned those treatments.

For example, according to the Journal of Military and Veterans' Health, arsenic was used as a treatment for leukemia as recently as the 1930s. Research is still ongoing as to whether it can be used as an effective cancer treatment, but arsenic is widely known to be poisonous. The ancient Greeks especially fancied themselves as philosophers of medicine, but they also had some strange ideas about how the body worked, such as that it was composed of four different humors, which must all be balanced. That theory has fallen away with time, but the ideas of some Greek physicians were trusted for thousands of years. Here are some ancient medications that did more harm than good.

Mercury: drops of silver in each hand

Syphilis has been treated with many different methods through the years, few of which worked. Left untreated, or ineffectively treated, a person suffering from syphilis will develop ulcers, fever, and muscle pains. The ulcers turn to pocks and sores all over the body, including in the throat and mouth. Eventually, their skin, bones, internal organs, nervous system, and cardiovascular system are irreversibly damaged.

The 16th century Swiss physician Paracelsus recommended treating syphilis sores with a mercury ointment, which was his preferred method because he was worried about the poisoning that could occur from drinking mercury, according to the Pharmaceutical Journal. He also recommended inhaling mercury fumes, or better yet, both at the same time. Paracelsus clearly saw mercury as a cure but was aware of the risks. People simply weren't careful enough. Unfortunately, prolonged exposure to mercury causes poisoning and eventual death. A known saying from the 15th century was "A night with Venus, and a lifetime with mercury," writes JMVH.

Mercury-based remedies remained available as recently as the early 20th century, but penicillin, developed in the 1940s, proved to be a much more effective, and much safer treatment for syphilis.

Opium: the poppy of sleep and death

Opium was used by the ancient Egyptians and Romans as a sleeping aid, according to History Extra. Roman doctor Galen recommended a particular shop to purchase an opium-based drink called cretic wine to help with sleep. But the risk of opium was known even back in ancient times. The Greek physician Dioscorides warned against overdosing. However, for Romans, suicide wasn't sinful, so some people suffering from old age or long illnesses chose opium as a pain-free way to end their lives. However, like most addictive drugs, the nature of opium probably made it difficult to know when to stop taking it and still live, if that was even what you wanted in the first place.

According to History Extra, opium was grown in Egypt on a large scale. Containers with opium residue have been found in Egyptian tombs. Going back even earlier, opium was grown in Mesopotamia. Historians also understand its importance due to the artistic depictions of the poppy on engravings and statues. In ancient Greek, the god of sleep, Hypnos, and the god of death, Thanatos, were also depicted with crowns of poppies.

According to Arcgis, opium treatments caused severe depression, which led to further dependence on the addictive drug. Opium also led to the discoveries of morphine and heroin, both of which are addictive as well. Opium's use ultimately led to thousands of deaths and several wars.

Tobacco: panacea plant of the Americas

When Christopher Columbus traveled to the Americas, he found Native Americans using tobacco to heal a number of ailments, including colds and fevers, according to an article in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. Columbus took tobacco back to Europe, where some doctors considered it to be a panacea and called it the "holy herb." However, the Franciscan monk Andre Thevet cautioned that tobacco caused fainting and frailty.

Columbus observed people in Cuba both smoking tobacco and using it to ward off illness, and tobacco was also used by Indigenous populations to whiten teeth, particularly when mixed with chalk or lime. Even in the 20th century, people used tobacco in various remedies, including to treat athlete's foot, and tobacco-based toothpaste continues to be sold commercially in India in the 21st century.

Of course, everyone now knows that tobacco causes cancer and lung problems, according to MedlinePlus, and has killed millions of people worldwide. Tobacco contains nicotine, which is an addictive substance. And, smoking tobacco is carcinogenic, but there are some calls to more fully study the leaves for substances of therapeutic value.

Excrement: to ward off spirits and avoid pregnancy

The ancient Egyptians used animal excrement to ward off spirits, for its health properties, and for contraception, according to Medical Daily. Though some animal dung contains antibiotic substances, it can also cause tetanus and other infections. Excrement in general has a tendency to spread disease.

In the 1600s, Irish physician Robert Boyle treated cataracts by drying human excrement, crushing it to a powder and blowing it into a patient's eyes. And there are reports of nosebleeds being treated with warmed pig excrement.

Today, medical professionals use human excrement, but mainly for diagnostic purposes. That said, fecal transplants can be used to treat recurrent colitis by replenishing bacterial balance, according to Johns Hopkins. This isn't an entirely new concept: In ancient China, sick people would also undergo what was then called "yellow soup," in which fecal matter from someone else would be made into a broth to treat diarrhea, as reported by the U.S. Department of Veterans' Affairs.

Feces will cause nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and a fever due to the bacteria in it, which includes E. coli and salmonella, writes Healthline. Those are all normal bacteria to have in your intestine, but not in your mouth. Hepatitis A and E are also in feces, which you can get by kissing someone's dirty hand, for example.

Leeches and bloodletting: balancing the body in the wrong way

Bloodletting has been used throughout history for thousands of years. For the Greeks, it was meant to balance the body's humors. Hippocrates believed the body was made up of four humors: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm, and that an imbalance among them caused illness. Diseases could be treated by removing an excess of a humor, for instance, by bloodletting via leeches, as described by the British Columbia Medical Journal.

However, as explained by All That Is Interesting, it was easy to draw more blood than was healthy without knowing it, and bloodletting could also invite infections. For example, in 1799, a physician was called to tend to George Washington, who was running a fever and having difficulty breathing. The physician, with the help of the caretaker of Mount Vernon, George Rawlins, let 3.75 liters of blood from Washington over the next several hours, in amounts of up to 18 ounces at a time.

Therefore, more than half of the blood in Washington's body was removed in an attempt to heal his illnesses. Washington died the next night of what was likely epiglottitis and shock. More to the point, it's practically impossible to heal when the element that's meant to be giving you life is taken away in large quantities. There's a reason why, when giving blood, the technician makes sure you won't pass out; humans aren't meant to give up so much at once. Extreme blood loss leads to death.

Cocaine: an addictive anesthesia

Cocaine (via coca leaves) was used by the Incas as a panacea. The Italian traveler Amerigo Vespucci wrote of Indigenous people using the plant in his memoirs (via Klin Oczna). The Incas chewed coca leaves to cure sadness, hunger, and tiredness. Though the Spanish colonizers originally did not trust the plant, they eventually saw that it stimulated the slaves they used to mine silver, according to Smart Drug Policy. Eventually, cocaine spread to Europe and the United States, where it was enjoyed as a tea and in chewing gum, as well as an anesthetic in surgery. Viennese ophthalmologist Carl Koller first used cocaine as an aesthetic in 1884, according to Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine.

Cocaine then became popular as a medicine in America and Europe. However, cocaine can lead to heart problems and strokes due to increasing the body's blood pressure (via Very Well Mind). Signs of cocaine abuse include depression, paranoia, and violent outbursts. It was eventually classified as a narcotic after being identified as having high social abuse potential, according to The Journal of Substance Abuse, and its medical use is highly restricted today.

Sulfur: fumigating the wandering womb

In ancient Greece, people believed that the womb was a separate entity that would move on its own around the body when a woman went too long without sexual activity. It was also thought that the womb had an inherent desire to produce children, according to Medical Independent. "Wandering womb" was the supposed cause of hysteria, suffocation, and seizures, along with several other conditions.

Sulfur was the medicine of choice for women experiencing wandering womb. They were fumigated in sulfur and pitch resin, while lotions were massaged onto their thighs. Women were also massaged and bathed. The idea was that the womb would be so disturbed by the bad odors that it would retreat safely to its natural position, notes Medical Independent. However, inhaling sulfur can negatively impact the nose, lungs, throat, and eyes, making it difficult to breathe, as well as swell the lungs, according to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Sulfur is now used mainly as sulfuric acid, which is put in batteries and fertilizers; it's clearly not meant to be inhaled. And of course, this medical condition didn't actually exist, making sulfur's use as a "cure" completely pointless.

Urine: terrible therapy for the self from the self

Urine has been hyped as a therapy for thousands of years, particularly for viral and bacterial infections. Instructions for this therapy have been found in artifacts from ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, as well as in Indian yogi texts and ancient Chinese documents. Urine is usually contaminated once it is outside the body, but not necessarily toxic. However, drinking urine can cause vomiting, diarrhea, and fever, according to The American Journal of Nephrology. It can also dehydrate a person.

A study in the Pan African Medical Journal describes some Nigerians giving urine to babies and young children who suffer from convulsions as a means of treatment. The 2010 paper says that the traditional therapy may be gaining popularity because of increasing poverty. Due to the warm climate, contamination and increase of bacteria in the urine is a real concern, though the lack of true medical treatment is a greater one. People using urine therapy also showed great resistance to common antibiotics.

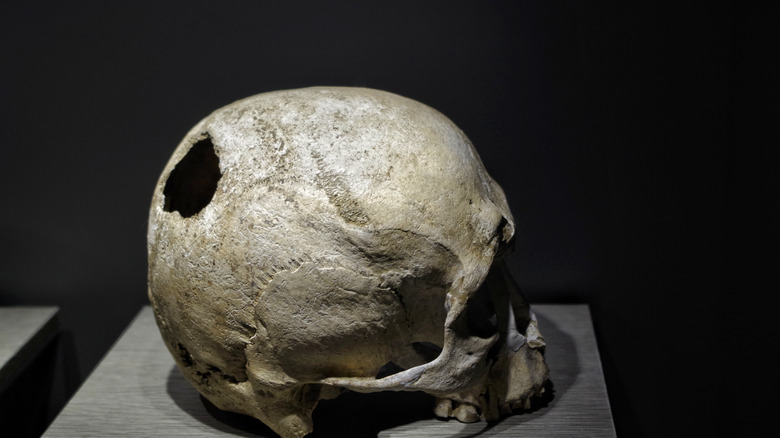

Trepanation: drilling holes in the skull

For thousands of years, humans practiced a crude form of surgery called trepanation, or cutting a hole in a person's skull by drilling, cutting, or scraping into the skin. Trepanation was likely performed due to pain in the skull or because of a neurologic disorder.

It is also postulated, writes BBC, that trepanation was done because it was a ritual. Even here, however, there were dangers. The trepanations found in a Copper Age-presumed family grave in Russia show that the holes were made at the obelion, a point towards the top and back of the skull. This is a particularly dangerous place to cut, because it's located just above where blood from the brain pauses before moving into the brain's outflowing veins; working here would have risked massive hemorrhage, yet people did it — and survived. However, other skeletons show that some people didn't survive long after the trepanning surgery.

Trepanation isn't practiced anymore, though the practice was kept alive until the 19th century.

Corpse medicine: blood from a dead man to cure a seizure

Consuming different parts of dead people has been medicine for thousands of years. Blood, bones, and fat have all been used for ailments in Europe. However, despite Charles II drinking crumbled pieces of a human skull in alcohol, he still died after seizures and excruciating medical treatments, writes Target Health. His doctors bled him severely after seizures, gave him enemas, and "medicinal" draughts. The king was then force-fed a drink containing alcohol and crushed skull on the third day of treatment, but died days later. His exact illness at his death is unknown.

Blood was thought to maintain vitality even after death, so it was used as medicine as quickly and freshly as possible, though this was difficult. The poor, who couldn't afford anything from an apothecary, would attend executions in order to pay for a cup of blood, fresh from the barely dead body, writes Smithsonian Magazine. Though all these "medicines" worked incidentally, a prevalent view was that the remains held the spirit of the body from which they had been taken.

Blood, however, causes vomiting when swallowed in large quantities, since the digestive system wasn't built to handle that. You could also develop heart and liver problems if your body absorbs too much of the excess iron in the blood you're drinking; the body doesn't have a way to get rid of it, and it isn't something that's healthy to take with you, writes Healthline.

Vicary Method: using chickens to cure the plague

The Black Death struck Europe from 1347 to 1352; it killed one-third of Europe, according to World History. Out of all the cures attempted for the Black Death, what was most successful was quarantine and social distancing. Avoiding interacting with family members and neighbors as best they could meant that everyone wasn't breathing the same infected air or spreading disease between each other due to close proximity.

Regardless, one such supposed cure was the Vicary Method, named after English doctor Thomas Vicary. A healthy chicken was plucked, then tied to the swollen nodes of the patient. When the chicken began getting sick, it was thought that the chicken was drawing out the sickness. Occasionally, the chicken was removed so it could be washed. However, with this "cure," eventually either the chicken or the patient died.

Eventually, patients resorted to avoiding thoughts of plagues or death, not sleeping during the day, and not exercising at all. The plague ended in 1352 after quarantines were lengthened to 40 days (via History).

Sweat: intense heat will save us

The sweating sickness swept across England during the first half of the 1500s. It disappeared soon after, and still fascinates historians. The sweating sickness would appear suddenly, causing pains, sweat, fever, and dehydration, and hours or days later the patient would be dead, writes History.

An ambitious man named John Kays (he later called himself Johannus Caius) began to treat nobles (seeing as how the disease seemed to strike them first), and advised them to sweat out the disease, drink herbal concoctions, and avoid going outside. These didn't necessarily help since sweating was how the illness killed. Extreme sweating and heat exhaustion can lead to heatstroke in the worst case scenario and cramps in the best, writes the Mayo Clinic. Heat exhaustion has similar symptoms as the sweating sickness had. Sweating is the body attempting to cool itself down, which is difficult to do in an already hot sickroom.

Though many of Kays' patients died of the disease, he still made enough money from them that he was able to donate to his Cambridge college, which renamed itself Caius College. Henry VIII remained terrified of the sweating sickness his entire reign, and several of his councilors took ill. According to Renaissancce Studies, Thomas More wrote regarding the illness: "One is safer on the battlefield than in the city."