The Reason Why These Animals Went Extinct

Extinctions are nothing new. It turns out that the turnover rate of life on Earth is about as fast as customers when the McRib is back at McDonald's... relatively speaking, at least. According to National Geographic, our planet has faced mass extinction on a global scale no less than five times. That includes the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs, but there's four other events, too, that make up the so-called Big Five mass extinctions.

As the calendar moves farther into the 21st century, scientists say the planet is facing a sixth. This time, it's not sky rocks or volcanoes, it's simply happening because — as a whole — mankind is around to become one of the most irrationally destructive species on the planet. And it makes no sense: Destroying the only planet we have to live on is kind of like peeing in the pool right before you take a nice, deep dive underwater, but that hasn't seemed to stop anyone.

Going back through history, researchers have found it's really nothing new. Extinction rates have been abnormally high since around the 16th century, and that's awful. What can we do about it? Well, let's start by looking at some of the species that are gone forever, and see what really happened to them.

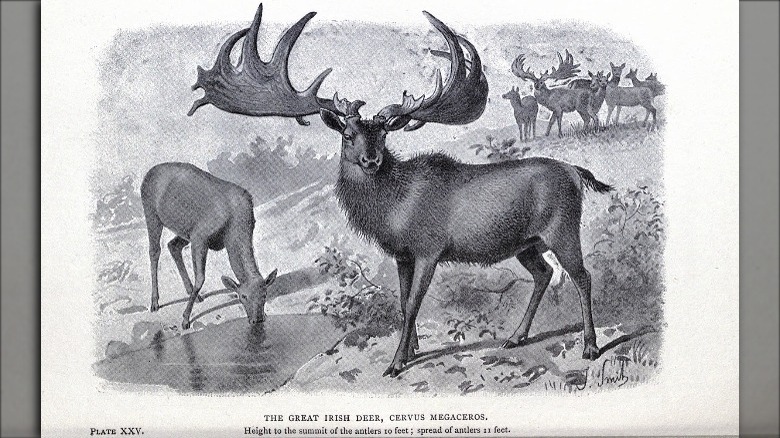

The mysteriously massive Irish elk

The name "Irish elk" is a complete misnomer: As the Smithsonian says, it wasn't exclusively Irish — it thrived across Europe for around 400,000 years — and it wasn't actually an elk; it was a deer.

Let's talk size: Males stood around 6 feet tall at the shoulder (via the Irish Independent), and they weighed around 1,500 pounds — which makes them about the size of a full-grown Clydesdale. Now, add on the antlers: Every year, males would grow an almost irrationally large set of antlers, which weighed around 90 pounds and averaged about 12 feet from tip to tip. Preserved antlers led to the rumor that the elk's extinction was caused when the antlers of the male simply got too big, and caused them to sink into bogs and break their necks when they got tangled. But Natural History Museum in London paleobiologist Adrian Lister says that's absolutely not the case.

For a long time, researchers blamed climate change. It was thought the last Irish elk died around 10,500 years ago, the time of a global cold spell called the Younger Dryas. Such big animals would have needed a lot of food, the theory went, but later findings show that the elk had been around for 3,000 years longer than originally thought. That puts the blame squarely on Stone Age people. Whether it was hunting or habitat loss remains unknown, but the current belief is that conflict with ancient people meant the end of these magnificent creatures.

A dubious honor for one of the world's only freshwater dolphins

In 2007, researchers from organizations like the NOAA Fisheries Service spent six weeks looking for traces of the Yangtze River dolphin in China. They found nothing, they reported in Science Daily, and the species was officially declared extinct (via The Guardian).

It was a long way to fall. At one time, the dolphin had been widely worshipped as being the reincarnated form of princesses who had drowned. That was pre-Mao... post-Mao, they were no longer a protected species, and became something to be hunted instead of treasured. As late as the 1950s, the Yangtze had supported thousands of these unique freshwater dolphins, but mass industrialization and a major increase in shipping traffic put serious pressure on the species as a whole. Over the years, the species was further damaged by unsustainable fishing. Conservation biologist Sam Turvey described it: "They just drift through the water snagging everything. They slash and entangle and suffocate the dolphins."

Turvey says that the extinction of the river dolphin meant not just the end of a species, but "the disappearance of a complete branch on the evolutionary tree of life." What's the dubious honor that goes with extinction? The Yangtze river dolphin is the first cetacean to be driven extinct solely because of conflict with and the actions of people.

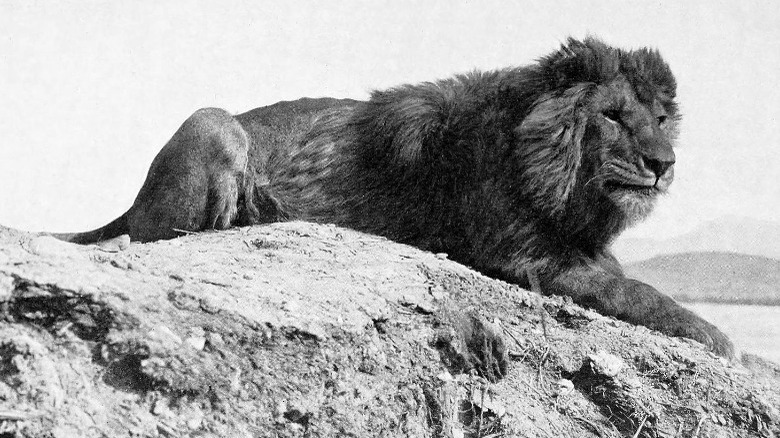

From widely admired lion to simply gone

The Barbary lion was a once-widespread subspecies of lion that lived across North Africa. It differed from other lions in two major ways — it was huge, and males sported dark manes. But first, a disclaimer: It's possible one might go to a zoo and see them boast of having a Barbary lion or two, but they're not actually real, purebred, distinct members of the Barbary lion species. They're descendants of the actual Barbary lions and do have Barbary lion genes, but the original species is long gone.

So, what happened to them? According to The Revelator, it was a long, slow death that started with the Romans. These were the lions that were sent to fight in the Colosseum, and it was also these lions that were also shipped off to royal courts from Morocco to the Tower of London. After the Romans killed thousands and thousands of these majestic cats came the pressure from European colonists who moved in and killed off whatever they didn't like... or were afraid of. It's long been said that the last lion was killed by a hunter in 1922, but when researchers started investigating later sightings, they found something else.

Now, it's believed the last Barbary lion was killed sometime between 1958 and 1965. The last sighting was during the French-Algerian War, and it's believed — but not confirmed — that the Barbary lion is one of the few species to be driven to extinction by war.

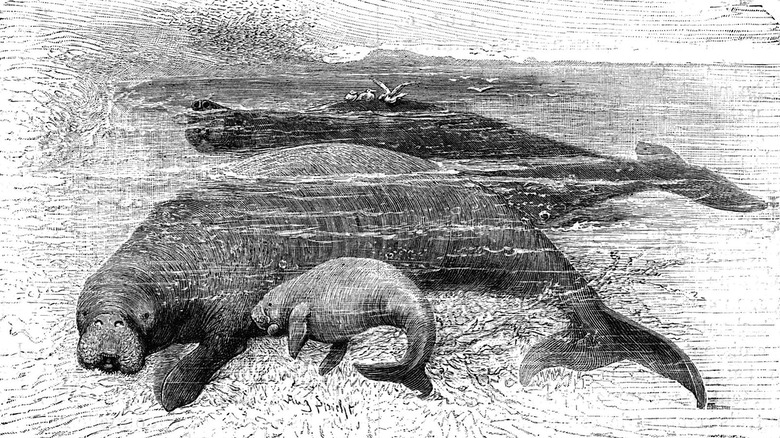

The heartbreaking fate of the Arctic Ocean's gentle giants

There's not a lot that's actually known about the massive creatures known as Steller's sea cows, because in the 27 years between their identification and their complete extinction, only a single scientist — Georg Wilhelm Steller — ever saw one alive. The only others to see living sea cows were those who were trying to kill them, and yes, that's absolutely why they're not around anymore.

According to the Natural History Museum, Steller's sea cows could grow to be more than 30 feet in length and weigh around 11 tons. And that was part of their downfall: A single sea cow was enough to feed a ship's crew for a month. Steller, a German zoologist, first documented the sea cow in 1741 in the Bering Sea. Unfortunately, they were right in the middle of prime hunting ground for fur traders looking to kill and skin vast numbers of sea otters to supply the fur trade and the fashion industry. As hunters moved through looking for otters, they'd kill sea cows to keep them supplied with meat for their journey between Russia, Japan, and North America. It was such a massive industry that by 1768, Steller's sea cows — which were probably rare when they were discovered — were completely extinct.

The museum's Principal Curator of Mammals, Richard Sabin, explains: "They are held up as an example of the first sea mammal in modern times made extinct by human ignorance and greed."

The most famous extinction of all

Everyone knows the story of the dodo bird, the fat little flightless turkey that was as helpless as it was tasty. European sailors landed on Mauritius, the story goes, and quickly hunted these goofy-looking birds to extinction. Right? It turns out, that's not actually the least bit true.

According to the BBC, the lies taught by high school science teachers everywhere starts with the plump, loveable image of the dodo. They weren't that chubby: History only remembers them like that because of a few chunky captives, and badly stuffed taxidermy ones. And that means they're not exactly the easy, filling meal they're usually portrayed as being.

So, if they weren't hunted to extinction, what happened? Now, it's thought that those same European sailors are still to blame, but the killing blow was a little different. Europeans weren't the only creatures those ships brought — they were also carrying rats, and a lot of them. Once rats were introduced to the ecosystem, that put the dodos' eggs in danger. Eggs were destroyed, numbers dropped off, and suddenly, the remaining dodos were also in pretty cutthroat competition for food. Dutch sailors landed on Mauritius in 1598, and by the 1660s, they were gone.

Wouldn't it be cool if there were American parrots? Well...

Parrots are some of the world's coolest birds, and yes, there was a parrot that was native to the U.S. It was just a single species called the Carolina parakeet, and they were brightly colored green, yellow, and orange birds. Cool, right? Unfortunately, we're talking about extinction, so you know where this is going.

According to National Geographic, the last Carolina parakeet was a captive one, and died in 1918. It was pretty shocking: At one time, they'd had a native habitat that reached from Florida to Pennsylvania to Nebraska. Recent studies have confirmed that yes, mankind is responsible for this one, too. Way to go, humans.

There were a few things working against the Carolina parakeet, and that includes rapid habitat loss thanks to expanding city and suburban centers. But they also had problems with farmers, who considered the once-large flocks they lived in to be nothing more than airborne pests. Not only did they kill individual birds, but Carolina parakeets were known for congregating around their dead, which allowed farmers to kill entire flocks at a time. They also suffered severe habitat loss due to clearing for the agricultural sector, and their feathers were so pretty that they became a popular fashion accessory when people decided they wanted to wear the feathers, instead of admiring the birds they belonged to. Now, no one can enjoy them.

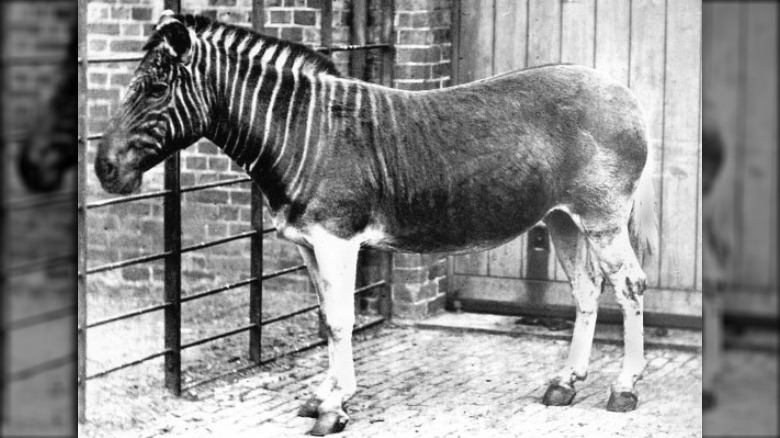

Just because science can bring something back... should they?

Here's a weird story, and it starts with the heartbreaking death of the last quagga. What's a quagga? It looks like a zebra that was 3D printed by a machine that was running out of toner, and only had enough for stripes on the top half.

Quagga used to roam Africa in great herds, but according to Wired, that ended with shocking speed. Once various Europeans decided to get on their colonial stompin' boots and hack and slash their way across the continent, the quagga was one of many casualties. For starters, they were wild animals that competed with domestic herds for resources. Add in edible meat and hides that were valuable to the leather industry, and you have a species that ended when one last mare died in the Amsterdam Zoo in 1883.

There's a weird footnote here. Advances in DNA testing mean that researchers have been able to examine the skin and skull of that last Quagga, and came to the conclusion that the funky-colored zebras were a subspecies of the Plains zebra, which still exists. Did science decide to mess with this? Of course! The Quagga Project kicked off in 1987, and in 2016, CNN announced that a selective breeding process — in which animals were selected mainly for their color pattern — had brought back six animals dubbed "Rau quaggas." Critics, however, are quick to point out that they're not actually quaggas, they just look like they are.

The bird that died under a sailor's boot

Sometimes, we know exactly when the last of a species died, and that's the case with the Great Auk. Standing about three feet tall, one of the last of these flightless birds was spotted by three Scottish sailors in 1840. Graceful in the water and ungainly on land, it was easy for them to catch the bird and carry it back to their ship. When they set sail and storms started, they became so convinced that the bird was a witch that had cursed them with the storm that they stoned it.

That was the last Great Auk of the British Isles, and the species died completely just four years later when fishermen chased and killed the last two — a breeding pair — and stepped on the last Great Auk egg. Explorers had been warning of the imminent destruction of the species since at least 1785. That, says the Smithsonian, is when George Cartwright condemned the practice of killing scores of Great Auks and collecting feathers for eiderdown.

Pre-16th century, there were hundreds of thousands of birds living in vast colonies along the northern Atlantic. By the mid-1500s, though, explorers had discovered the treasure trove of eggs and meat, and helped themselves without a second thought. Ships hunted — then salted and preserved — them by the barrel, and even though there were attempts made to save them, a single Great Auk specimen was simply worth too much money for people to resist.

The prehistoric ancestor of modern cattle

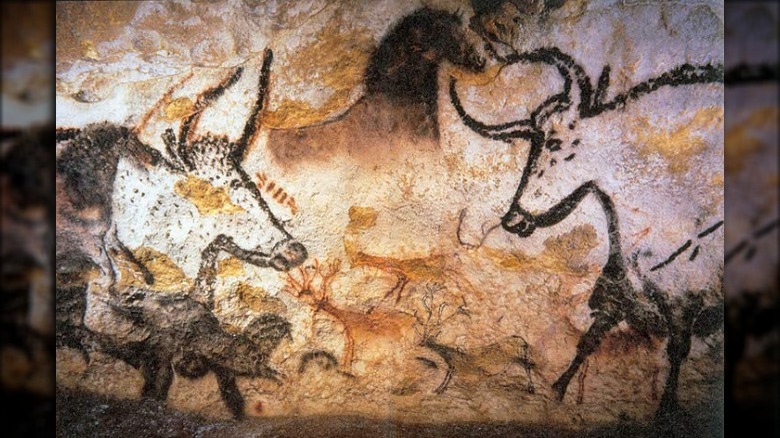

Cows today might seem — for the most part — pretty harmless. They weren't always that way. Imagine an elephant. Now, imagine the biggest, baddest, most muscle-bound steer possible... only the same size as that elephant. That was the aurochs. Discover Magazine says they've been around for a long time, even immortalized in cave paintings dating back 30,000 years. Julius Caesar described them: "In size these are little but inferior to elephants. They spare neither men nor beast."

They were once plentiful, until mankind got in the way and made aurochs the first recorded species to go extinct. Where they were once spread out across the forests of northern Africa, all of Europe, and into Asia, they started feeling the pressure from the relentless multiplication of mankind. By the early 1600s, they had been pushed out of so much of their habitat that they only lived in a single area in Poland: Jaktorow Forest. It was there that the last aurochs died, in 1627.

It's entirely possible they might make a return. In an attempt to create a large creature that could graze wide areas and help stabilize crumbling ecosystems, the Taros program started by gene sampling modern breeds and finding aurochs genes. With a selective cross-breeding program, they're approaching the re-creation of something very similar to the ancient beasts (via CNN). (On a side note, this isn't the first time it's been attempted — attempts at creating an Aryan aurochs were linked to the Nazis.)

The birds once so abundant they were called the 'living wind'

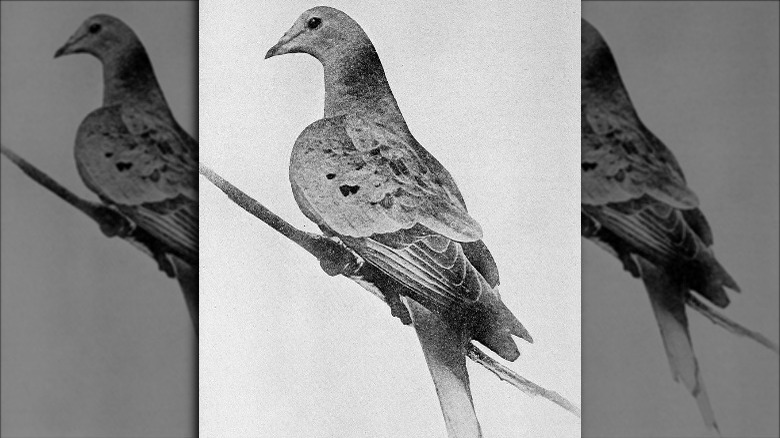

Audubon estimates that in their heyday, the passenger pigeon was at least the most numerous bird on the North American continent. Author and conservationist Aldo Leopold called them "a living wind," and when Potawatomi tribal leader Simon Pokagon wrote about them in 1850, he described flocks as sounding like "an army of horses laden with sleigh bells was advancing." Birds traveled in flocks of hundreds of thousands of individuals, with some estimated to be in the millions. So many would nest in trees that their collective weight would snap branches... so, what the heck happened?

The last passenger pigeon died in 1941. Her name was Martha (pictured), and she was 29 years old. By that time, the species had been destroyed by mass slaughter that included everything from poisoned corn to swatting them out of the sky with poles to simply shooting them.

Seen as both a nuisance and a source of easy meat, the development of the telegraph and improvements to the country's transportation system allowed people to essentially follow the flocks — and find new ones. An entire industry formed around the wholesale slaughter of the pigeons, leading Pokagon to later wonder what otherworldly justice was "awaiting our white neighbors who have so wantonly butchered and driven from our forests these wild pigeons, the most beautiful flowers of the animal creation of North America."

Once, the world had a blue antelope

The aptly named bluebuck was an antelope named after its bluish fur, and it first trotted onto widest expanses of South Africa around half a million years ago. The last one was killed in 1800, and while ThoughtCo. says that it's easy to blame the appearance of European colonists, it's not entirely their fault.

Just a little bit. Like... half.

Bluebucks were widespread across the African plains, but this massive, 10-foot-long, 400-pound antelope was first seriously hurt by the Ice Age. By about 3,000 years after the end of the last Ice Age, their habitat and food sources had dwindled to the point where it impacted their numbers. Then, humans showed up for the first time — sometime around 400 BC — and started forcing the bluebuck off the grazing land that was left, ironically at the same time they considered the animals sacred. By the time Europeans moved in, they cleared the land of the remaining bluebucks, stuffed a few individuals for museums, and then, they were gone.

Australia's most unique marsupial

Take a dingo. Now, give it the coloring of a zebra on the back end, and a pouch like a kangaroo... only, make that pouch open to the back instead of to the front. That's pretty much an explanation of the creature known as the Tasmanian Wolf, Tasmanian Tiger, or thylacine. The Australian Museum says that the thylacine was the only one of that particular branch of the evolutionary tree that was around in our modern era, and guess what happened to them?

The last captive thylacine died in 1936, says MongaBay, and for a long time, it was believed that a farmer named Wilfred Batty shot and killed the last wild thylacine in Tasmania in 1930. (It's currently thought they survived much longer than that — into the 21st century — but that hasn't been proven.)

For the most part, thylacines hunted birds, rodents, and the occasional kangaroo. When Europeans settled Australia, though, they quickly gained a reputation — which may have been completely undeserved — for hunting domestic livestock like sheep and chickens. Scientists believe that it was a perfect storm of factors that pushed this pouched dog to extinction, including widespread hunting by farmers claiming to be protecting their livestock, conflict with dogs introduced by Europeans, and habitat loss that pushed them into close competition with Australia's native dingoes. (And now, some dingoes — like the Australian alpine dingo — are classified as vulnerable to extinction.)

Lonesome George might not have been so lonesome after all

For years, the Pinta Island tortoise called Lonesome George (pictured) was the poster boy for conservation efforts. He lived at the Charles Darwin Research Station in the Galapagos Islands, and when he died on June 24, 2012, the world mourned the loss of an entire species.

The 200-pound, 5-foot-long tortoise was actually on the small side for his species, which could reach double that weight, and have an average lifespan of around 150 years. (Lonesome George was about 100 when he died.) According to ThoughtCo., the event that pushed the tortoises to the brink was the arrival of whalers and commercial fishing crews in the 19th century. Not only did they love to eat the easy meals that the tortoises were, but they also introduced goats that ate the same thing the slow-moving tortoises did.

The Pinta Island tortoise is now considered extinct, but that might not be the end of the story. Genetic researchers from Flinders University and Yale University have re-discovered not the Pinta Island Tortoise, but the species' DNA. An expedition to the Galapagos turned up a handful of hybrid tortoises, and of the 1,600 tested, 17 carried Pinta DNA. Some have been moved to captive breeding facilities, where researchers say (via The Conversation) that they're going to try to selectively breed survivors to revive the pieces of DNA that are left.

The horse the Nazis tried to resurrect

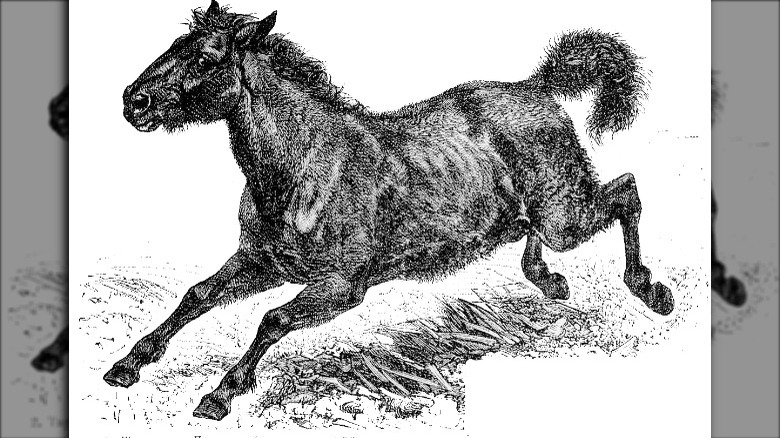

The story of the tarpan is a weird one, and it starts way back in prehistory. According to ThoughtCo., the tarpan emerged victorious after an Ice Age wiped out all their cousins, and it was the tarpan that was first domesticated by early humans. Ancient Roman writings talk about the vast herds of tarpans that ran wild, and here's where humans start ruining things.

By the 18th century, these wild horses were already nearly extinct. Why? Partially because they were tasty, and were widely slaughtered for their meat. There was another problem, though: Since they were capable of interbreeding with domestic horses, that's exactly what they did. The result was fewer and fewer pure tarpans left in the wild, and the last died — while being chased by people — in 1879. Eight years later, the last captive died.

But here's where things get super weird. In Nazi Germany, a zoologist named Lutz Heck decided that he was going to reverse engineer horses into tarpans by selectively breeding for certain traits, like hardiness, appearance, and super-fast healing abilities. And the Smithsonian says that he sort of did. He ended up creating a breed that still lives in the forests of Poland, and while they're still tainted by their association with the Nazis, the so-called near-tarpans are now credited with helping to stabilize the ecosystem of Bialowieza.

The loneliest — and most naive — animal of all

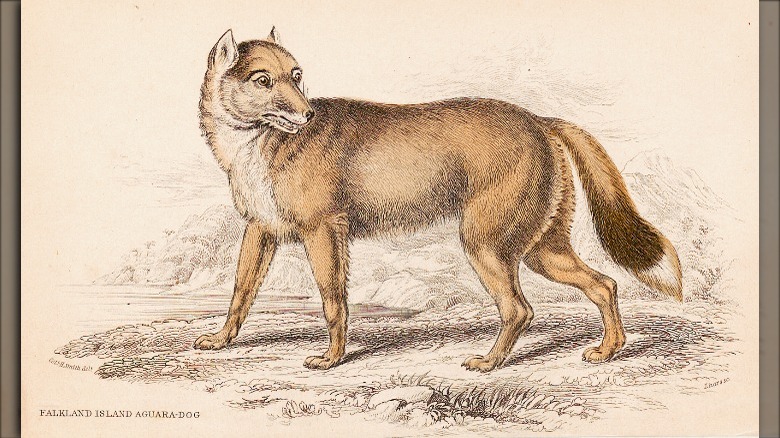

It wasn't that long ago that the Falkland Islands were home to a single mammal: the Falkland Islands wolf. How it got there was a fascinating mystery that was only recently solved (we think). According to National Geographic, the wolf made the journey from South America to the islands at a time when the distance from one to the other was only around 12 miles. As the ice receded, the gap widened, and the size of the Falkland Islands themselves began to shrink, the wolf was essentially marooned. Good news for it: It had no predators, and a buffet of sea birds and rodents to feast on.

And it turns out that predator-free isolation gave researchers a clue as to why they were extinct by 1880. The first landing on the islands happened in 1690, with the first settlement following in 1764 (via the BBC). When sailors went ashore, they were shocked to be greeted by a super-friendly dog who was so excited to see these wonderful and new two-legged creatures that were coming to visit them that they'd often swim out to meet approaching ships. The wolf's scientific name, Dusicyon australis, even translates to "foolish dog of the south."

And if there's anything that's easy to kill, it's a super-affectionate dog. That's exactly what happened: the Falkland Islands wolf was clubbed, knifed, beaten, and baited to death by those not-so-wonderful two-legged creatures it was so happy to see.

From millions... to none

As the world entered the dawn of the 20th century, there were somewhere around a million black rhinos living in areas across Africa. They were officially declared extinct in 2011. So, what the heck happened? According to Scientific American, fortunes started changing for the western black rhino with the development of sport and trophy hunting. That put a serious dent in the population, and that was followed up by the clearing of land and culling of rhinos as commercial and industrial agriculture became more important than native species.

By that time, it was the 1950s, and here's where Chairman Mao comes in. Not only did Mao Zedong take over China, but he also started guiding the nation's daily life. That included the promotion of traditional Chinese medicine, and even though he didn't actually believe in it, he was an incredibly vocal proponent of the use of things like powdered rhino horn. It was said to cure pretty much anything, and it was in such high demand that when poachers realized they could make a fortune slaughtering animals for their horns, that's what they did. By 1980, there were only 135 western black rhinos left, and they were spread so far apart that there was little chance of them meeting — or of making new rhinos.

By 1997, there were 10 left. Six of them died alone, miles apart.

The sea wolves of the Caribbean

When Columbus was sailing through the Caribbean, he and his crew were greeted by creatures they called "sea wolves." The Smithsonian says they were equal parts exotic, captivating, and — unfortunately — delicious, which is part of the reason why there are no more monk seals in the Caribbean.

The creatures Columbus called sea wolves were more recently known as Caribbean monk seals, and they were very, very, very distant relatives of the Mediterranean monk seal. They split in their evolutionary tree somewhere around 6.3 million years ago, and after between 3 and 4 million years of separation, they ended up forming completely distinct species.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says that it wasn't that long ago that there were 13 colonies of the monk seals, and as many as 338,000 individuals. Those seals were hunted first by newly-arrived Europeans who saw them as a source for oil, pelts, and food. Groups and colonies were destroyed, and ironically, there was a massive scramble at the turn of the 20th century to capture some of the remaining specimens. So many were killed in the process, captured, and shipped off to research facilities and zoos that it destroyed the last remaining wild colony. By 1952, there was only one small group left in the wild, and although they were only declared officially extinct in 2008, it's believed that they had disappeared decades before.

When one extinction might give another species hope

In 2011, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service took a look at the species that it had listed as endangered. On the list was a North American big cat called the eastern cougar, and it had been lingering for a long time. The species was officially declared extinct in 2018.

Officials think that it had been a long time coming, and say that most eastern cougars had died in the 1800s. As people expanded their territory, these big cats were hit with a triple whammy: Not only did they lose their natural habitat, but their favored prey — white-tailed deer — was slaughtered wholesale by those same encroaching humans, and those humans were also killing the cats themselves. Why? Because they were scary, and they had pelts that were incredibly useful.

National Geographic says that the problem with pinpointing just when the eastern cougar went extinct happens because they're incredibly solitary, shy creatures who travel at night and prefer to avoid people. They also say that confirming the cats' extinction might work out all right, and could help protect other big cats. Conservationists are seeing an across-the-board decline in large predators, which is leading to an unbalanced ecosystem. It'd be awesome if people learned from cases like the eastern cougar, and it was perhaps Michael Robinson of the Center for Biological Diversity who put it best when he said, "To know the world is not entirely dominated by humanity is a peace of mind."