The Untold Truth Of The Paralympic Games

Coinciding with the Winter and Summer Olympics, the Paralympic Games hosts athletes with physical and sensory disabilities, not to be confused with the Special Olympics, which hosts athletes with intellectual disabilities. And although disabled athletes have competed against one another for hundreds of years, the official Paralympic games didn't start until the mid-20th century.

While the first Paralympic game only hosted about 400 athletes, since then, the Paralympic games have expanded to include over 4,000 athletes from over 160 countries. And since the end of the 20th century, the Paralympic Games have also been held in the same city as the corresponding Olympics.

Despite the fact that the Paralympics is the second largest international sporting event in the world, it often receives a muted reception from the media. And even amongst the International Olympic Committee, the Paralympics is sometimes treated like an afterthought. However, disability activists such as Caroline Casey believe that the 2021 Paralympics might offer an opportunity to "challenge the perceptions of inclusivity," especially since the coronavirus pandemic not only "exposed the 'gross inequity and injustice' suffered by people with disabilities," but is causing a huge rise in disability as well. This is the untold truth of the Paralympic Games.

Competitive sports in disabled communities

Some of the first recorded instances of competitive sports organized by disabled communities come from the 19th century. The creation of the Sport Club for the Deaf in Berlin, Germany in 1888 is considered to be one of the first sporting organizations for disabled people, according to "(Dis)empowering Paralympic histories" by Danielle Peers. The Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, Massachusetts had sports teams at least from 1909.

In 1924, the First International Silent Games, now considered the first iteration of the Deaflympics, was organized by Eugène Reuben‐Alcais and Antoine Dresse, both deaf themselves, writes Deaflympics. This was the first ever international sports competition for people with disabilities and after the modern-day Olympics, was the only the second ever international games competition. The Deaflympics continue to this day, and unlike other International Olympic Committee sanctioned events, the Deaflympics are "organized and run exclusively by members of the community they serve. Only deaf people are eligible to serve on the ICSD [The International Committee of Sports for the Deaf] board and executive bodies." However, as noted in JRSH, although "the Deaflympics were important as an indication of possibility, [they] retained a separate existence from the movement that would create the Paralympics."

According to "History and Development of the Paralympic Games," there were also a number of sports clubs for those with physical disabilities prior to the 1940s, "including the British Society of One-Armed Golfers and the 'Disabled Drivers' Motor Club."

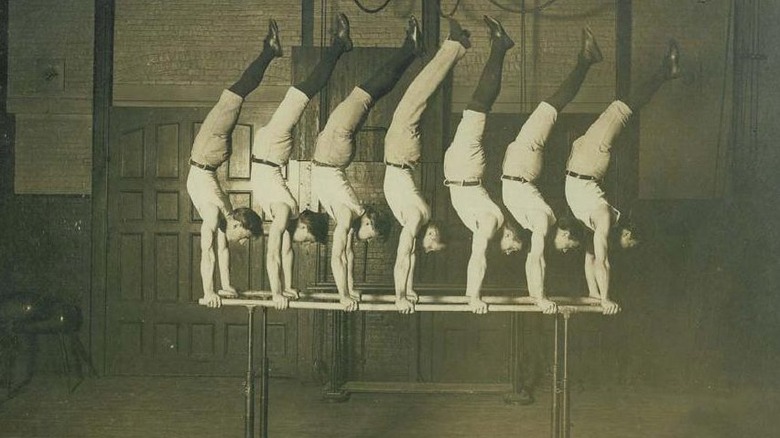

Disabled athletes in the Olympics

Before the creation of the Paralympics, there were numerous athletes with disabilities that competed in the Olympic Games. In 1904, the Summer Olympics were held outside of Europe for the first time, in the United States, and it was during these games that gymnast George Eyser won six Olympic medals, including three gold ones, in a single day. According to Everything Everywhere, Eyser had lost his left leg during his youth when he was run over by a train and used a wooden prosthetic leg. Eyser continued to make a name for himself in gymnastics after the 1904 Olympics, going on to compete with the ultimately winning team in the 1908 World Championships in Frankfurt, Germany. He was also victorious in the 1909 National Championship in Cincinnati, Ohio.

We Capable writes that the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics also included several disabled athletes. Oliver Halassy, who similarly suffered a streetcar accident during his youth that resulted in the loss of his left calf, competed on the Hungarian water polo team in 1928, 1932, and 1936. On top of that, he was "a freestyle swimming champion."

Donald Golan, a deaf and mute athlete, was part of the United Kingdom's rowing team in the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, where they won silver. And Carlo Orlandi, an Italian boxer who was born deaf and mute, won the gold medal in the lightweight division.

Dr. Ludwig Guttmann and paralyzed war veterans

In 1943, Dr. Ludwig Guttmann started working as the Director of the National Spinal Injuries Unit at the Stoke Mandeville Hospital. But although he's typically credited with starting the Paralympian games, Peers notes in "(Dis)empowering Paralympic histories" that sporting games "were invented by inmates of Stoke Mandeville before Guttmann even began his sporting programs there." At Stoke Mandeville Hospital, Guttmann reportedly introduced sport to patients with spinal cord injuries and spinal paraplegics as a rehabilitation activity. With this, Guttmann focused on the "therapeutic value" of sport. These games included darts, snooker, ball throwing, wheelchair polo, and archery.

Historic England writes that one of the first competitions occurred in 1944 at Ward X. Known as a "competitive 'dressing exercise,'" the patients raced one another to see who could get up from their beds, get dressed, and get into their wheelchairs the fastest.

The first version of the Games was known as the "Stoke Mandeville Games for the Paralyzed" or the "1948 Wheelchair Games," since all of the participants used wheelchairs, and was held on July 29th, 1948, coinciding with the opening day of the 1948 London Olympics. There were 16 competitors, two of whom were women. By 1952, the games were renamed the 1st International Stoke Mandeville Games after Dutch ex-servicemen also joined.

The first official Paralympics

The first official Paralympic Games were held in Rome, Italy in 1960 with eight games: archery, Para athletics, dartchery, snooker, Para swimming, table tennis, fencing, and basketball. However at this time, "the only disability that was included was spinal cord injury," according to Inside The Games. Up to 400 athletes with varying degrees of paralysis from 23 countries came to participate in the Paralympics. According to "History and Development of the Paralympic Games," the 1960 Paralympic games were "considered a huge success," although accessible accommodations were the main problem for many.

The Paralympics continued to center around paralyzed athletes until 1976, when the Paralympics in Toronto allowed for amputees and blind athletes to take part as well. And in 1980, there were events at the Arnhem 1980 Paralympics for athletes with cerebral palsy.

However, the Paralympics wasn't always held in the same city as the Olympics. According to JRSH, the International Olympic Committee "was only interested in candidate cities' abilities to meet the needs of elite athletes and made no stipulation that the Olympic city must hold parallel games for athletes with disabilities ... [this led to] a succession of cities effectively refusing to stage the Paralympics." Mexico City declined the Paralympic games in 1968 due to "technical difficulties" and "Two games and one movement?" writes that in 1980, Olympic organizers in Moscow ignored the requests for the Paralympics by claiming that there were "'no disabled citizens in the USSR' making the games unnecessary."

Origins of the name

The Ninth International Stoke Mandeville Games was considered the first official Paralympic Games, held in 1960, but it wasn't until the 1964 Tokyo Summer Games that "Paralympic" was included in written form. However, according to the National Museum of American History, the medals awarded were at the time inscribed with "The Tokyo Games for the Physically Handicapped."

Despite the homophonic nature of the words and the fact that they have the same root, the Paralympics has nothing to do with the term "paraplegic." But the name is similarly derived from the Greek word "para," which means "beside" or "alongside." This is meant to convey that the Paralympics run in parallel with the Olympics and "illustrates how the two movements exist side-by-side," according to the International Paralympic Committee.

And in "Guttmann's ingenuity," Cobus Rademeyer writes that the name "Paralympic Games" wasn't officially recognized by the International Olympic Committee until 1984. But once it was recognized, it "was then backdated to include the 1960 Paralympic Games in Rome."

The 1992 Korean boccia team

During the 1992 Paralympics, the Korean boccia team won the bronze medal. But according to "(Dis)empowering Paralympic histories" by Danielle Peers, the team members threw down their bronze medals onto the ground as a protest against a new "sport-specific rule."

Unfortunately, little more is known about the Korean athletes' protest. In "Athlete First," Steve Bailey writes that the protest was regarding "the reporting time prior to competition." It's unclear what the athletes hoped to accomplish with their protest, what their responses to the sanctions they received were, or whether or not their protest was at all successful. Even their names aren't recorded in the accounts of their protests. As Jeffrey J. Martin writes in "Handbook of Disability Sport and Exercise Psychology," "ascertaining the details of their protest is difficult. I failed in my efforts, as might be the case for both Peers and Bailey."

In response to the protest, the Paralympic executive committee decided to ban the athletes for life. In comparison, someone with a positive steroid test only received a four-year ban. The ban was eventually lifted in 1996, "largely due to arguments that it was not 'humane' to ban athletes who were so 'severely disabled.'" As Peers notes, "the Paralympic experts explicitly set out to undermine resistance through extreme sanctions, and then implicitly undermined athlete power through discourses of tragic disability."

Trischa Zorn: the most successful Paralympic athlete

Trischa Zorn is known as the most decorated Paralympian athlete of all time due to her total of 55 medals, 41 gold, 9 silver, and 5 bronze, which she won over the course of seven Paralympic games. According to Long Beach State University, Zorn was born with aniridia, a congenital eye condition that causes visual impairment and blindness. "Before Zorn received surgery, she could only see objects that were a few feet in front of her. After the surgery, her vision improved from 20/1100 to 20/850."

Team USA writes that Zorn competed in multiple swimming events as a multi-stroke athlete, including the freestyle, butterfly, and backstroke, from the 1980 Arnheim Paralympics to the 2004 Athens Paralympics. In 2012, she was inducted into the Paralympic Hall of Fame, and according to the United States Olympic & Paralympic Museum, USA Swimming created the Trischa L. Zorn Award in her honor "for a swimmer or relay team with a disability for outstanding performance and excellence."

During the 2000 Paralympics, Zorn was also attending Indiana University Law School and after getting her law degree, as of 2020, she works at the Department of Veterans Affairs in the fiduciary department.

Setting new world records

Throughout her athletic career, Trischa Zorn set at least eight Paralympic world records in swimming. And she wasn't the only Paralympian setting world records. In 2008, the Beijing Paralympics "saw a total of 279 new world records set and a total of 339 new Paralympic records broken."

And according to Independent, in the 2016 Paralympics, Abdellatif Baka of Algeria, Tamiru Demisse of Ethiopia, Henry Kirwa of Kenya, and Fouad Baka, Abdellatif's brother, all finished the 1500m race "faster than [the 2016] Rio Olympics gold medal winning time."

In 2021, German athlete Markus Rehm went on to beat his own T64 long jump world record by almost 5 inches. And Spain's Kim Lopez, who was the Rio 2016 shot putter champion, also set a world record of 17.02m in the men's F12 shot putter competition, "improving by 33cm the previous record set by Ukraine's Roman Danyliuk at the Dubai 2019 World Para Athletics Championships."

Criticism over lack of funding

The Paralympic Games have repeatedly been criticized for their lack of funding. And often, as Jamie T. Green notes in the Independent, it "isn't an issue with logistics, it comes down to the fact that funding for the Paralympics [is] diverted to boost the Olympics." During the 2016 Rio Olympics, funding that was meant to be set aside for the Paralympics was instead "spent on renovations to the Olympic village."

According to Inside the Game, the disparity in sport funding in the United Kingdom for their Olympic and Paralympic teams is stark; "£265 million ($368 million) versus £71 million ($98 million) for the Tokyo 2020 cycle." As Ed Warner notes, "If every medal is deemed equal, which is the official line, then one can only conclude that UK Sport believes Paralympic medals can be won at lower cost than Olympic ones."

The New York Times reports that in 2003, American Paralympic athletes Jacob Heilveil, Scot Hollonbeck, and Tony Iniguez sued the United States Olympic Committee, alleging that they were deliberately underfunding Paralympic athletes. While there were discrepancies, ultimately the courts ruled that "the U.S.O.C. had not violated federal antidiscrimination laws in funding the groups differently." But by the time the lawsuit came to a close in 2008, "the U.S.O.C. had more than tripled its financing of Paralympic athletes during the life of the lawsuit."

International coverage of the Paralympics

Despite the fact that the Paralympics is a major international sporting event, numerous countries provide them with little media coverage. According to The Guardian, the International Paralympic Committee called out NBC in 2012 for not broadcasting the Paralympics live. In comparison, Great Britain offered "over 400 hours of coverage on Channel 4, 150 hours of it in prime time." And while NBC offered comparatively more coverage in 2016 Rio Paralympics than they did in the 2012 London Paralympics, "the absence of reporters and photographers with a U.S. passport [was still] notable," according to The Conversation.

Even when the Paralympics is taking place in that very city, little effort will be made to promote it. The Sudbury Star writes that at the 2014 Winter Games "in Sochi, there [was] little sign the Paralympics [were] even taking place in the city. There [was] very little done to promote the Games, much less any specific event of any of the athletes competing."

And when the Paralympics are promoted, disabled people are actively erased. In 2016, Rolling Stone wrote that "Vogue Brazil decided to promote the games by hiring two models and digitally removing two limbs to make them look like amputees." Unfortunately, as Marie Hardin writes, "people with disabilities have historically been excluded from the sport-media complex because of their failure to meet the hegemonically prescribed ideals of physicality. Thus, noncoverage of athletes with disabilities is the norm for American media."

'Disability focused athleticism'

Ultimately, the Paralympics don't seem to do much in terms of increasing disabled people's participation in sports. The Conversation writes that after Paralympic events, the number of disabled people participating in sports clubs shows "no noticeable change[s] in membership." However, this is heavily impacted by the fact that "many sports organizations [are] unprepared for the level of interest from disabled people and [are] unable to respond accordingly." And as Jay Coakley and Elizabeth Pike note in "Age and Ability," "Being inspired by Paralympic athletes [does] nothing to eliminate negative attitudes, increase funding for disability sports, improve accessibility to venues, provide convenient transportation, or create knowledgeable and experienced coaches and support staff."

But according to Rolling Stone, for many disability advocates and disabled athletes, the Paralympics is less significant than "their own leagues and the experiences of re-discovering their body through sports." As athlete Sam de Leve notes, "To a great extent, the Paralympics tries to play to a nondisabled audience (can't blame them, that's where the money is, and they desperately need it!), but we use sport as part of creating our own disability culture, and seeing ourselves as a community with shared history and culture is important and even radical."

Ultimately, according to "A mockery of equality," by Stuart Braye, Kevin Dixon, and Tom Gibbons, while the Paralympic Movement generally tries to push for equality in sports, some disability activists "see the Paralympics as a hindrance to equality."