The Mythology Of Sea Monks Explained

There's something missing in today's world, and it includes things like maps with things like "Here be Dragons" written on them.

Scientists, philosophers, researchers, and just generally curious people have learned a lot about our world in the last few hundred years, and while that's great, it seems like we've lost something along the way. We no longer experience the excitement of seeing new worlds on the horizon, encountering entire lands of new and strange animals, and making weird discoveries like the sea monk. Or, at least coming up with such fascinating explanations for what we're looking at.

Today, the sea monk has been filed into the category of creatures that may have existed, but that definitely weren't what everyone thought they were. So, what was the strange creature from the sea, first recorded in the 1500s? Answering that is complicated, but before analyzing the evidence, let's give our ancestors some serious kudos for their imaginations. This is the mythology of sea monks explained.

The sea monk first appeared in the 16th century

The sea monk first appeared in the middle of the 16th century, but let's put that in some context, because it's kind of important to know a bit about what was going on at the time to understand just where the whole sea monk idea came from.

This period was, History Central says, the same time that the whole Protestant vs. Catholic thing was really kicking off in earnest. The Holy Roman Emperor was going to war to try to force Protestant areas of Europe back into the fold, rebellion was widespread, Jews were being shuffled off to ghettos, and, in 1558, Queen Elizabeth I took the English throne.

It was against that backdrop of religious conflict that the French naturalist Pierre Belon first described the creature that the Smithsonian says had washed up, perhaps, on a beach somewhere in the vicinity of Copenhagen. Maybe. It's also possible that it had been caught in the waters of the Oresund — the strait that separates Sweden and Denmark — but it's not entirely clear.

Belon documented the finding in 1553, and there are a few important footnotes. For one, he didn't actually see the creature — he'd only heard about it. And secondly, it had actually been found (or caught) years earlier, some time between 1545 and 1550. It's no wonder that there was much debate over the creature even in the 1550s.

It looked like, well, a monk that came from the sea

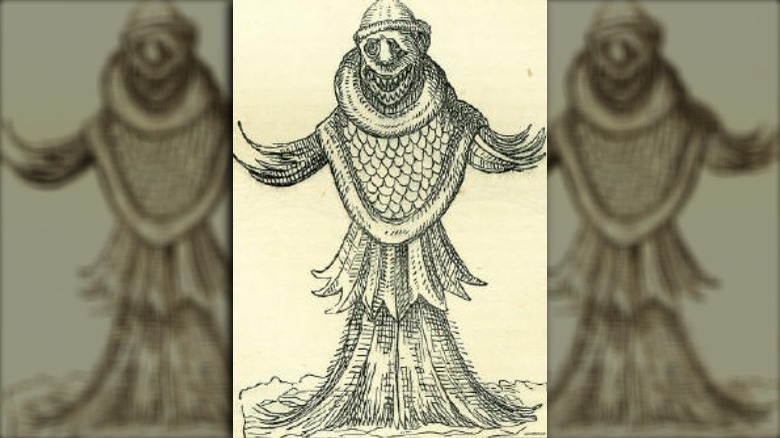

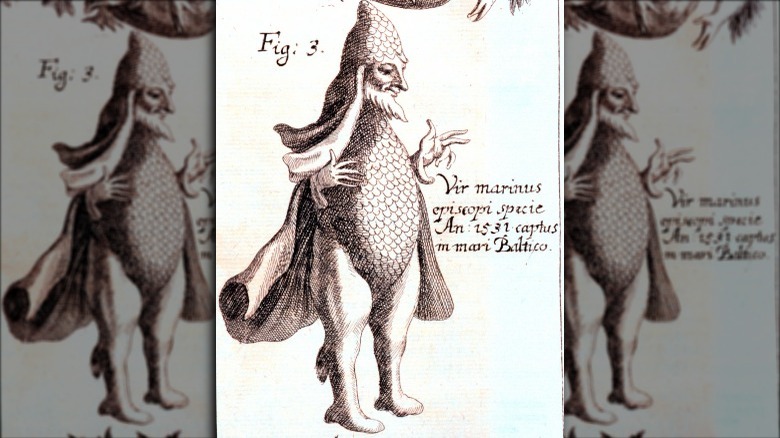

French naturalist Pierre Belon first described and sketched the sea monk, complete with fins, flippers, and a regal-looking "robe," all covered with scales and topped by the tonsured head of a human monk (via the Smithsonian).

The following year, Guillaume Rondelet — another French naturalist — wrote more about the sea monk, and reported that it was 8 feet long (or tall?), had an impressive tail fin, two other fins about midway on the body, and a black head.

Once the works of the two French scholars were translated, copied, and distributed, the Edward Worth Library says that the continent (or at least the natural history community) was hit with sea monk fever. Everyone wanted to know what the heck was going on with this weird, apparently sea-dwelling holy man, and who can blame them?

While history may have forgotten a lot of the details of the discovery of that first creature, there's something fascinating in Rondelet's version. His text makes it clear that he's perfectly aware of just how crazy this whole thing looks and sounds, and while he doesn't say with 100% certainty that it's a real thing, he does say the source is beyond reproach. He got his information from Marguerite of Navarre, wife of the King of Navarre and the sister of the French king Francis I. She had been sent the information from Denmark's King Christian III, and he'd gotten it from the messenger who'd seen the creature in question.

Some were said to be man-eating monsters

The 1540-something sighting of the sea monk is generally said to be the one that got everyone talking, but later researchers who compiled historical references to the sea monk found that it had been referenced much, much earlier.

Albertus Magnus (pictured, and who the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy reports was also known as Albert the Great) was a philosopher, zoologist, psychologist, meteorologist, and all-around Renaissance man who just happened to live in the Middle Ages. He was born sometime around 1200, and in his work "De Animalibus," he makes mention of the creature.

Magnus wrote: "Certain people say the sea monk is a fish occasionally seen in the British sea. It is a fish with white skin on the top of its head, around which is a dark circle, like the head of a monk who has been recently tonsured."

He clearly states it's a fish, but he adds one more bit that makes it seem a bit more human than animal. He described it as having "the mouth and jaws of a fish," but added that it was known for "entic[ing] those travelling on the sea until it lures them in." Then, Magnus wrote, it disappeared into the watery depths and "takes its fill of their flesh."

Yes, it was alive when it was found

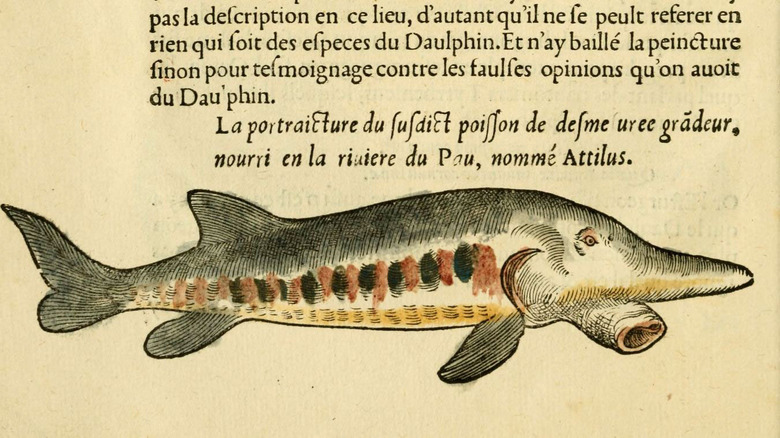

It's also worth mentioning that Pierre Belon wasn't just some random guy that wrote books about whatever crazy stuff he'd heard about that day. Corpus Christi College Oxford calls him the "founder of early modern ichthyology" — the scientific study of fish — and says that he was one of the first to create a series of drawings of sea creatures (including the one pictured), and then categorize them based on anatomical similarities. He was the real deal, even if he did get some things technically wrong (like including the hippo in his book about fish).

He's also credited for some incredibly accurate drawings: He did the first illustration of a chameleon that was actually right.

Belon wrote that the first sea monk had been found off the coast of Norway, and he adds something that's actually pretty heartbreaking. According to the Edward Worth Library, he wrote, "This monster, according to many who saw it, did not live more than three days, did not speak nor emitted any sound but great, plaintive signs." Put it back in the water, guys!

There's a lot of explanations for what sea monks might have been

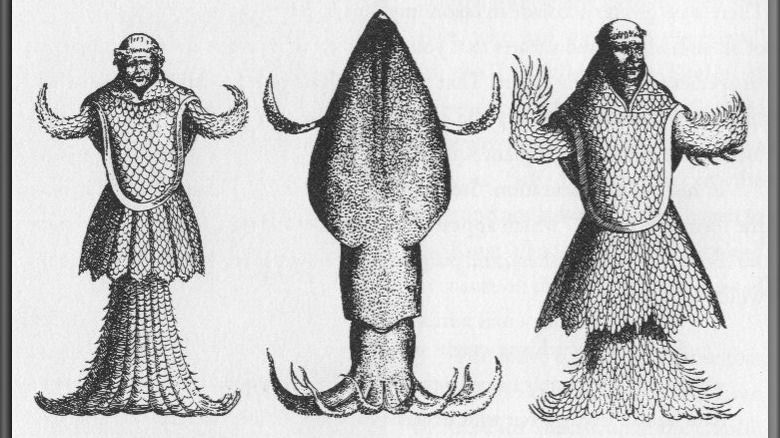

In 2005, researchers from the Freshwater Biological Association and the University of St. Andrews took a crack at trying to figure out what poor creature might have been plucked from the sea and described as the sea monk. They started by compiling historical sketches of the creature, along with guesses that previous biologists had made, starting with Japetus Steenstrup.

Steenstrup was writing in 1855, and he was so sure that what everyone had called the sea monk was a type of giant squid that he actually gave the species a name: Architeuthis monachus. He argued that the monk's mantle resembled the squid's head, the coloring looked very much like scales, the tentacles could have been mistaken for arms and legs, and the distinct possibility that a squid could have lived for a few days out of the water.

Not everyone has been happy with that explanation, in part because giant squid aren't known to live in the area that the sea monk was reported to be found.

So, other ideas have been put forward, including the possibility it was an angel shark, an anglerfish, a walrus, or one of a number of different types of seals, including a monk seal. When they laid out the characteristics and compared them to the sea monk, there were difficulties with each one. Ultimately, the researchers concluded that the sea monk "will remain an enigma," which is science-speak for, "No clue!"

Contemporary Christian beliefs added another fascinating layer to the mystery

The religious connotations of the name sea monk are pretty obvious, but it's entirely possible the name is a clue to something else that's going on with this creature.

Take people like Aegidius Albertinus, who was a member of the counter-Reformation. According to SMU's Perkins School of Theology, members of the counter-Reformation met regularly between 1545 and 1563 to reassert and reestablish Roman Catholic doctrine, and Albertinus suggested that the appearance of the sea monk wasn't a coincidence. He believed (via the Universiteit Leiden) that the creature was a direct message from God, and the message was that the clergy was corrupt and rife with hypocrisy.

The Edward Worth Library suggests something else, saying that perhaps the sea monk should be viewed along with a heavy dose of religious cynicism. The library points out that other animal-clergy hybrids, like the monk calf and the papal ass, had previously been used to point out the corruption and problems within the Catholic Church, and encourage reform, along with conversion to Protestantism. Was the sea monk meant to be used in the same way? Some suggest it was.

Was the sea monk a ploy by a clever king?

Context can be everything. Let's take a look at Denmark's King Christian III (pictured). He was the one who sent word of the sea monk to a high-standing member of the French court, and it's entirely possible that he had more on his mind than just sharing knowledge and a love of cryptozoology.

In 1536, Denmark's new king seized all the lands that belonged to the church and put himself in charge of the nation's new Lutheran Church. If there were any questions about whether Christian III was going to side with the Roman Catholics or the Protestant Reformation, he gave the answer loud and clear. But in doing so, he faced a serious problem. Now, Science Nordic says, he needed other nations to see this new Denmark as a continued, legitimate nation, government, and aristocracy.

What does any of that have to do with the sea monk? Researchers from the Edward Worth Library suggest that Christian III sent a description of this amazing, incredible, weird, monk-like sea creature off to France in order to "raise the profile of Denmark." It couldn't hurt, right? The library also suggests that it paid off: Christian III's Denmark was part of a major alliance formed just after reports of the sea monk circulated.

Was it just another Jenny Haniver?

There's another explanation for the sea monk, and it's a little more cynical. The Smithsonian says that through the years, many have suggested the creature was something called a Jenny Haniver. What's that?

Anyone who's ever gone on vacation to some exotic locale knows the pressure to bring back the right souvenir, and things were pretty much the same during the Age of Exploration. The Vintage News says that sailors would sometimes find dead skates, rays, or other fish, and then dry the skeletons, fashion new parts from other materials, and lacquer the whole thing to make it look like one piece. The resulting items were presented as dragons or mermaids, according to Atlas Obscura. Not too many people make them today, but the practice hung around well into the 20th century — mostly thanks to guys like PT Barnum.

Perhaps its relevant that the first Jenny Haniver is thought to have been made in the 1550s, the same time as the sea monk story was making the rounds. In fact, the very first written reference to the Jenny Haniver was in Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner's "Historia Animalium," which also included reference to the sea monk.

There was a sea bishop, too

As if the idea of a half-human, half-fish monk living under the sea wasn't weird enough, there's also written records of a sea bishop, too.

Guillaume Rondelet — who was the second to write about the sea monk, in 1554 — also told the story of the sea bishop. According to the Edward Worth Library, Rondelet wrote that a doctor named Gilbertus Germanus had told him that a creature he described "as a fish in a bishop's habit," had been presented to the king of Poland. The creature had reportedly — somehow — indicated that he wanted to go back into the ocean, and according to the tale, when the Polish king obliged, the creature blessed him.

Rondelet regarded this story with a healthy dose of skepticism, too, but it has been suggested that the tale was told about the remains of a creature that was likely either a ray or a skate.

What did contemporary naturalists really believe?

So, did people in the 16th century really believe there was some sort of race of fishy humanoids living below the waters, adopting Catholicism and handing out blessings to their fishy brethren?

Louisa Mackenzie, a University of Washington professor of French and Italian studies, says that they didn't. She suggests (via the Smithsonian) that "it's very possible that naturalists believed it to be a true hybrid, and that, possibly, was to be feared."

According to the same source, Charles G.M. Paxton of the University of St. Andrews has a slightly different interpretation, and suggests the problem is us, not them. He says it's entirely possible 16th century researchers had simply decided to describe what they were seeing in terms that everyone would understand, and "a fish shaped kind of like a monk" turned into the sea monk. Whoops. That kind of misunderstanding has actually happened before. Take a look at olde-timey ocean maps, and many include fantastic sea monsters out in the oceans. Those, says Strange Science, weren't all supposed to be real. Some were labeled, while others were not — suggesting that while some were thought to be real, others were simply decorations.

The combination of sea and land creatures was common

The sea monk is a combination of a land-dwelling creature and a sea-dwelling one, and it's worth mentioning that when word got out about them, that part wasn't considered all that odd. Instead of thinking, "Hey, that's a super-weird creature that's half-land, half-sea," most people probably would have thought something along the lines of, "Hey, there's another fish in the sea that looks like something we have on the farm."

As the Leiden Arts in Society Blog points out, medieval texts included animals like the sea-cow, described as being the front half of a cow and the back half of a fish, which makes more sense than if it had been the other way around. The hippocampus (pictured) was another odd creature thought to exist in this time. It was half-horse, half-fish. Further, according to the Smithsonian, contemporary maps feature decorative illustrations with elements plucked from biology and naturalist drawings, including animals like sea dogs and sea pigs.

It all sounds a little strange, but in some cases, the stuff we've actually found in the oceans is even weirder.

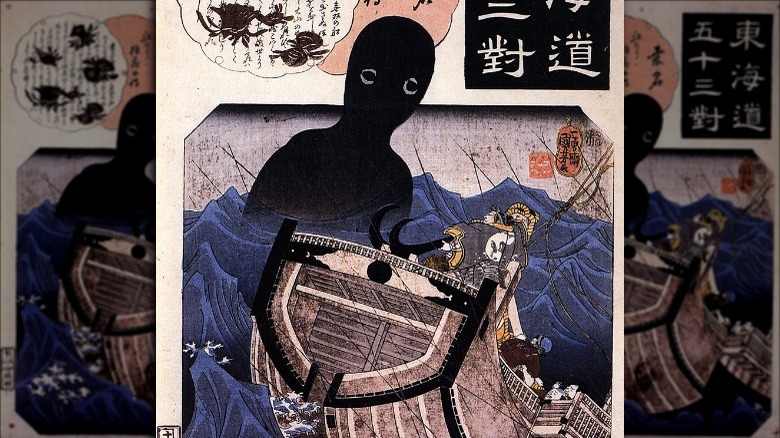

Japan also had a sea monk

The idea of a sea monk isn't actually unique to Western cultures. The umibozu is a creature from Japanese folklore, and it's called the sea monk because it has a smooth, bald head — just like a Buddhist monk. Stories are varied, according to Orca Spirit, but it's generally associated with storms. Legend has it that the creatures can rise 10 feet out of the water, and they're known for trying to sink ships and break masts.

According to the Public Domain Review, one myth tells of Kawanaya Tokuzo, who decided to set sail on the last day of the year, which was considered to be an unlucky day to be out at ocean. His actions summoned the sea monk. The creature demanded that he share the most horrible thing that he knew of, and when he answered, "My job!" the sea monk retreated, taking the storm with him.

It's been suggested that the Japanese sea monk is connected to natural phenomena: Sightings of rogue waves, giant jellyfish, or sea turtles could have given rise to the myth.

History is rich with stories of fossils and skeletons inspiring mythical beasts

If the sea monk really is a creature that was created by the combination of the creepy-looking remains of an actual sea creature and an overactive imagination, it's worth mentioning that it's not alone — this sort of thing happened all the time.

A 2020 exhibit at London's Natural History Museum (via the Smithsonian) demonstrated just how many mythical creatures have their basis in the skeletal remains of very real animals. The manatee, for example, has a skeleton that — if you sort of squint and look at it sideways — resembles a mermaid. It's easy to see how a giant squid could become a kraken, and how the massive skull of an elephant could be reimagined as a cyclops.

Other things are less obvious. Dragons, says LiveScience, got a boost in credibility thanks to the bones of a swordfish, which were said to be the remains of the dragon's tongue. That particular bone was kept in an Austrian monastery as evidence of a dragon reportedly killed in 1240. (Fun fact: When the church started looking for the remains of the dragon's companion, a giant named Aimon, they didn't find any. The entire church collapsed around the failed archaeological hunt.)

While science may have debunked many of these tales, the true story of the sea monk remains a mystery. And that's okay: A little mystery is good.