The Long History Of Skateboarding Explained

Many of the most prominent modern sports are rooted in rules and tradition. They have painted lines and boundaries, referees, rules that can be broken. But skateboarding is another matter entirely, built on breaking rules and making new ones, on taking risks and rolling outside the lines. It's more about community than competition. And many say it isn't a sport at all.

Skateboarding is highly adaptable to individual needs, mindsets, and skill levels. To some, it's an extreme sport; to others, it's simply another method of transportation. But more than anything, skateboarding has become a way of life. What began as an underground activity took to the streets and became a cultural phenomenon with growing mainstream appeal (for better or worse). It has infiltrated various forms of art, including video games, film, fashion, and music. The evolution of skateboarding has followed a nonlinear path and gone through periods of decline, but the sport (or hobby, or lifestyle) has ultimately zigzagged uphill.

Skateboarding has its roots in roller-skating, surfing, and scootering

In California and Hawaii in the early 1950s, surfers began attaching wheels to short surfboards and riding them through the palm tree-lined streets. According to Skate Deluxe, these innovative surfer dudes were deemed "asphalt surfers." Some see so-called asphalt surfing as the genesis of skateboarding.

Others trace skateboarding back a few more decades, to the similarly D.I.Y. kick scooters. According to Ben Marcus' "The Skateboard: The Good, the Rad, and the Gnarly: An Illustrated History," kick scooters were often made out of pieces of wood or metal with wheels attached. Riders controlled the contraption via their back foot, while keeping their front foot onboard. The first known scooter patent dates back to 1921.

Going back even further, scooters evolved from roller skates, which date back to the late 18th century. By the late 20st century, skateboarding innovations such as polyurethane wheels (more on that later) were in turn influencing and enhancing the world of roller skating, per The New Yorker.

Skateboards began as postwar toys

During World War II, fun in America required a certain amount of resourcefulness. According to the Museum of Play, one manifestation of this was in children making scooters out of milk crates and fruit boxes with roller-skate wheels attached. Some kids would remove the front boxes, which served as makeshift handlebars for grip, and end up just skating with the bottom boxes-on-wheels. (Marty McFly's wooden skateboard in 1985's "Back to the Future" was a similar contraption.)

Once the war ended, shiny new toys appeared back on the market. In 1953, a company called Roller Derby opened its factory in La Miranda, California. In 1957, the company launched the first booted, outdoor "Street King" roller skates, per Ben Marcus' "The Skateboard: The Good, the Rad, and the Gnarly: An Illustrated History." Street King skates became the best-selling roller skates of all time. In 1959, Roller Derby released the world's first mass-produced skateboard, which were first sold in nationwide roller derby links before making it into the Sears mail-order catalog.

1960s developments added to the athleticism of skateboarding

In the 1960s, skateboards shifted from simple toys to versatile sporting equipment. In 1965, Life magazine described skateboarding as "the most exhilarating and dangerous joyriding device this side of the hot rod," adding, "A two-foot piece of wood or plastic mounted on wheels, it yields to the skillful user the excitements of skiing or surfing. To the unskilled it gives the effect of having stepped on a banana peel while dashing down the back stairs. It is also a menace to limb and even to life."

Various factors contributed to this shift. According to Skate Deluxe, the first skateboarding contest was held in Hermosa Beach, California, in 1963. Skaters began to experiment with new styles of riding, which was made even more possible by Larry Stevens' invention of the "kicktail," or the upturned ends of a skateboard. Companies began sponsoring skateboarders like any other athletes. The first skateboarding-focused magazine, "The Quarterly Skateboarder," was published in 1964.

Another pivotal event was the establishment of the Vans shoe company, as noted by SI. On May 16, 1966, the company began selling rubber-soled shoes in Anaheim, California. By the early 1970s, Vans were widely considered to be the ultimate skateboarding shoe.

The invention of urethane wheels in 1972 changed skateboarding

In 1972, Frank Nasworthy invented polyurethane wheels and changed skateboarding forever. Produced by his company Cadillac Wheels, the urethane was highly durable and made turning on a skateboard much smoother than with the clay and steel wheels that came before, per Museum of Play.

According to Sh*tMag, Nasworthy grew inspired to try alternative wheel materials after observing kids trying to skate in empty pools. He noted the smoothness of polyurethane and invested $700 he made while working in a restaurant into the Cadillac Wheels Company. At the time, skateboarding was experiencing its first major lull. Many thought it had been a passing fad. So Nasworthy used surf-focused avenues to showcase his wares, selling the new wheels in surf shops and advertising in surf magazines. By 1975, Nasworthy was selling 300,000 sets of polyurethane wheels each year.

Another significant 1970s development, likely aided by polyurethane wheels, was the rise of the "ollie." According to Skate Deluxe, Alan Gelfand came up with the maneuver, which is essentially a hands-free leap into the air on a skateboard, in 1978. The trick gave rise to the street skating that would dominate the decades to come.

Zephyr skateboarders took skateboarding to the next level as a subculture

In 1972, the same year Frank Nasworthy invented urethane wheels, another pivotal element of skateboarding history was born: The Zephyr Surf Team. According to The Culture Trip, the team arose out of a local surf shop that year, and its members were known for surfing through the industrial scraps that littered the area. On the west side of Los Angeles stood a decaying pier called Pacific Ocean Park, locally known as POP Pier. When the rebellious Zephyr surfer kids weren't catching waves, they were skateboarding through the area's surrounding streets. The group's members included Jay Adams, Tony Alva, Jim Muir, and a pioneering woman named Peggy Oki.

In the early 1970s, a drought hit southern California, drying up swimming pools for miles. The Zephyr group began skateboarding in the empty pools, ultimately creating the "vert style" of skateboarding, which was later adopted by skateboarders like Tony Hawk. The Zephyr group, which became known as the Z-Boys, amplified street skating as a counterculture phenomenon. "Our only crime was being original and we are Possessed To Skate after all these years," reads Dogtown Skateboards' about page. The Zephyr story was shared on the big screen by the 2001 documentary "Dogtown and Z-Boys" and the 2005 drama movie "Lords of Dogtown."

Safety concerns have plagued skateboarding

By the 1970s, skateparks had become commonplace across the United States. The parks of the time were vast landscapes of concrete. According to Live About, the insurance policies on skateparks were astronomical due to the risk factors involved and the fact that most parks were privately owned. As a result, safety gear was enforced on skatepark premises.

Prior to the '70s, skaters had no choice but to use protective gear that was intended for other sports, such as basketball and hockey, per Transworld. But the spread of skateparks brought about skateboarding-specific gear. In 1977, Mike Rector invented the Rector pad, a plastic-capped safety pad that allowed skaters to knee-slide without any gory aftermath. "Knee-sliding had a huge impact on the industry and was the reason skaters wore pads," Rector said. "Instead of wearing pads in case you fell, skaters were wearing pads so they were able to fall to their knees and slide out unhurt."

By the end of the decade, liability issues and intense insurance policies caused many skateparks to close, bringing skateboarding to the streets. Safety gear was less necessary when it came to street skating, so many skateboarders put their kneepads aside. Today, the potential for skateboarding injuries remains high, but popular magazines and videos usually show skateboarders sans safety gear.

Major skateboarding magazines began in the 1980s

With the rise of street skating by the 1980s, skateboarding transcended the realms of games and sports and entered the realms of culture and a lifestyle. In January 1981, a group of skateboarders in San Francisco, California, created Thrasher magazine. The magazine is now, according to its website, the longest-running and best-selling skateboarding magazine of all time.

At the beginning of summer of 1983, came Volume 1, No. 1 of Transworld Skateboarding Magazine. While Thrasher was a counterculture publication with a penchant for sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll, Transworld was a more kid-friendly take on the skate 'zine. "They were pretty harsh, sex and drugs and using four-letter words and all that and in the early '80s, the sport started growing and [Thrasher] wasn't the best magazine for young kids," co-founder Larry Balma told the Union-Tribune in 2003 (via Smithsonian). In contrast to Thrasher's "skate and destroy," Transworld's motto was "skate and create."

The 1995 Extreme Games amplified skateboarding as a sport

In 1995, ESPN executives launched The Extreme Games. The games were designed to cater to the emerging batch of athletes and sports fans who were edgy daredevils rather than football bros. According to the official X Games website, the first event was held in Newport, Rhode Island in the summer of '95. It showcased BMX, bungee jumping, skateboarding, and beyond. According to Time, the event reportedly cost $10 million and drew 200,000 spectators. The Extreme Games — which later became known as The X Games — grew exponentially from there.

After the first year of Extreme Games, a USA Today columnist dubbed the sporting event the "Look Ma, No Hands Olympics," adding, "Apparently — and it's possible I'm misinterpreting a cultural trend here — if you strap your best friend to the hood of a '72 Ford Falcon, drive it over a cliff, juggle three babies and a chainsaw on the way down and land safely while performing a handstand, they'll tape it, show it and call it a new sport" (via Time).

Still, this new — if a little unorthodox — ESPN event made skateboarding more visible and commercial. It brought money and mainstream cred into skateboarding and helped make way for the sport as a profession.

Today, skateboarding influences the movie world...

In the early days of pop skateboarding, Stacy Peralta, an original member of the Zephyr Skate Crew, shot films of "vert" skate competitions on professional video equipment. According to Premium Beat, Peralta's videos were released on VHS tapes with the title "The Bones Brigade Video Show." But skateboarding film as we now know it came along later, with the invention of the handheld camcorder. With their first video, 1988's "Shackle Me Not," a skate collective called H-Street pioneered the modern skate video aesthetic: lo-fi and D.I.Y. elements, fisheye lenses, clips of skaters showing their personalities between tricks.

Before long, skate filmography was leaking into Hollywood. Skate films were already out there, including the Oscar-nominated 1965 short film "Skaterdater." The iconic skateboarding scene in 1985's "Back to the Future" inspired a generation of skaters, including Patrick O'Dell, who later created the Viceland skateboarding documentary series "Epicly Later'd," per The Ringer.

But things took off further in the post-skate-video world of the 1990s. Spike Jonze, who is now known for directing movies like "Being John Malkovich" and "Her," got his start in the skateboarding world. Perhaps the most impactful skateboarding movie — which isn't really about skateboarding at all — is Larry Clark's "Kids." The 1995 cult classic featured a cast of real-life skate kids and was written by the then-teenaged-skateboarder Harmony Korine. And it reflected back at the skate world the grungy, handmade aesthetic originally cultivated by skate videographers.

... the music world ...

In the summer of 1964, rock duo Jan and Dean performed the song "Sidewalk Surfin'" on Dick Clark's TV show "American Bandstand." According to the Museum of Play, the performance helped further amplify skateboarding in mainstream American culture. The song was written by Brian Wilson, founder of the ultimate surf band the Beach Boys, and featured lyrics like, "Grab your board and go sidewalk surfin' with me/Don't be afraid to try the newest sport around" (via Genius).

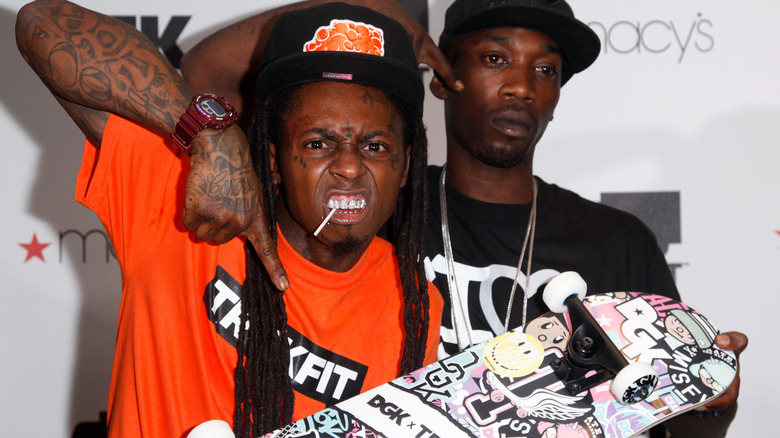

The next few decades saw the rise of punk bands who released albums laden with teen angst and anti-authority messaging — a natural pairing with skate culture. Following the foundations laid down by bands like Bad Religion, skate culture became significantly intertwined with punk rock as the 1990s became the 2000s. Blink-182 achieved astronomical success with their late-90s and early-00s skate punk records, and Avril Lavigne released the on-the-nose single "Sk8er Boi" in 2002. Starting in 1995, the skate shoe brand Vans sponsored a music festival that became known as The Vans Warped Tour and focused on punk rock. Today, the skate torch is carried by genre-spanning musicians from Mac DeMarco to Tyler, The Creator.

...and even the world of high fashion

In 2016, Dior Homme showcased its Fall/Winter collection on a runway surrounded by skateboarding ramps and half-pipes. Six months later, Vogue published a series of articles and editorials as part of its "Skate Week," which drew cringes and mockery from the skateboarding world, as noted by Complex.

The seeping of skateboarding into the mainstream fashion world began five years earlier, with the 2011 collaboration between streetwear brand Supreme and skate magazine Thrasher, according to Andrew Luecke, co-author of the book "COOL: Style, Sound, and Subversion." According to skateboarding magazine Jenkem, Supreme was "the fashion world's gateway drug into skateboarding." The brand began as a small skate shop on the Lower East Side and is now a phenomenon that was worth close to $40 million by 2017, per Esquire. Shortly after the collaboration debuted, celebrities like Rihanna and Justin Bieber were wearing t-shirts emblazoned with Thrasher's flaming logo. Vogue deemed Thrasher t-shirts "every cool model's off-duty staple."

The issue, according to Jenkem, is that it's high-fashion designers and fast-fashion corporations who are profiting from the trendiness of skateboarding, rather than actual skate brands. "Skaters...they've historically been outcasts," skate-fashion businessman Brendon Babenzien told Esquire. "One day you're an outcast and the next day everybody wants to wear the clothes you're into and lay claim to it? You're going to be a little annoyed by that."

In 2021, Team USA assembled its first-ever Olympic skateboarding team

On June 21, 2021, Go Skateboarding Day, USA Skateboarding announced that an official US skateboarding team would compete in the delayed 2020 Olympics in Tokyo, per Forbes. It's the first year skateboarding will have been included as an Olympic sport. The 12-person team included three men and three women in each of the two categories, park skating and street skating.

Still, the historic announcement drew some criticism from the skateboarding community — including those who are on the Olympic team themselves. "There is this, like, sportification of skateboarding happening, but skateboarding itself is not a sport," women's street skater Alexis Sablone said on HBO's "Real Sports" in June 2021. "The best part of skateboarding is about style and counterculture and we don't play by the rules. It's like, 'I'm going to make this up and do it my own way.' That's what I love about skateboarding."

Even Tony Hawk, who was announced as a Tokyo Summer Games correspondent in July 2021, said he was ambivalent during a March 2021 interview with Yahoo Finance. "You know, I have a bit of a mixed feeling, obviously, about the Olympics because I feel like we were never looking for their validation," he said. "And if anything, they need our cool factor for their summer games to bring in a younger viewership ... But at the same time, I see the benefits of it. And I'm excited that these places where people have been discouraged from skating will now be embraced for it."