Giant Prehistoric Insects That No Longer Exist

One of Merriam-Webster's definitions for the word "insect" is "a trivial or contemptible person." It's no wonder that some people like to use it as a pejorative, especially when they want to make others feel insignificant. After all, the real-world animals that inspired this insult are small: the longest insect in the world is only about 2-feet long, while most of today's big bugs can easily fit in your hand.

Hundreds of millions of years ago, however, the Earth was a vastly different place. The air had about 10 to 14% more oxygen than it does today (via EarthSky). While nearly all animals need oxygen to live, too much of it can be toxic. According to National Geographic, insects in this period likely grew larger to control their oxygen intake. Having bigger bodies meant they could handle the high oxygen levels in the air better than if they had stayed small. In addition, there weren't really a lot of creatures around that time (aside from proto-birds and insectivorous dinosaurs) that could curb their growth, may have been what allowed prehistoric insects to become considerably bigger than their modern counterparts.

While these gigantic invertebrates didn't make it to the present day, the fossil record has revealed quite a bit about these fascinating ancient arthropods. Here are some of the largest extinct insects to ever fly or crawl on the planet.

A dragonfly with a wingspan the size of a baby

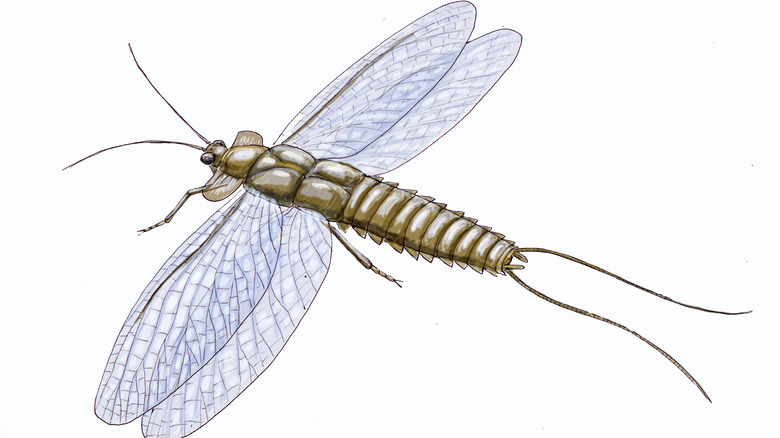

Among all the massive bugs scientists have unearthed, a dragonfly-like creature first found in the late 1930s holds the title of largest prehistoric insect. Meganeuropsis permiana was collected and described by renowned paleoentomologist Frank M. Carpenter from a rock formation in Dickinson County, Kansas. The Museum of Comparative Zoology currently houses the holotype fossil, or the main specimen used as a basis for a new species' name and description.

According to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, this long-gone giant came into existence approximately 275 million years ago, during the late Permian period. (That's around 45 million years before the first dinosaurs popped up!) Based on reconstructions of partial fossils, M. permiana's wings likely grew up to 2.5 feet in length, which is about as big as a one-year-old baby. In life, it would have weighed more than a can of soda (450 grams, or about a pound).

M. permiana and other species from the extinct Meganeura insect group are typically called giant dragonflies, which is a bit misleading. It's more accurate to call them griffinflies, due to certain structural differences that set them apart from their much smaller counterparts (via National Geographic). As Michael Anissimov explains in an article on InfoBloom, one of the biggest differences between griffinflies and dragonflies is in their wing vein patterns; while Meganeura insects had nearly identical front and back wing patterns, today's dragonflies don't.

A hummingbird-sized ant

When people hear about ants, they usually picture something small. Despite their size, however, most folks know better than to mess with them. One example is the aptly named bullet ant, whose bite packs an incredibly painful punch for something that only grows about an inch long. Now, imagine an ant twice as large; it's not hard to understand why Bruce Archibald, the paleoentomologist who reported the discovery of Titanomyrma lubei, called the nearly 50-million-year-old insect "monstrously big" (via LiveScience).

Around as big as today's hummingbirds, T. lubei was first discovered in the Green River Formation, a fossil bed in Wyoming. The specimen actually spent a bit of time in storage at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science before a curator picked it up and showed it to Archibald, who immediately realized it was an "exciting" find. It's worth noting that despite its size, T. lubei isn't the largest ant ever found; in fact, the queen of a still-living ant species is slightly bigger, according to Wired.

Unfortunately, not much is known about the ant aside from the fact that it had wings; much about its traits and way of life remain a mystery. What paleoentomologists can tell from it, however, is that it likely crossed an Arctic land bridge to reach America all the way from Europe, at a time when Earth was getting warmer (via BBC).

The largest six-winged insect

During the Carboniferous period approximately 311 to 307 million years ago, a massive insect called Mazothairos enormis flapped its wings across certain parts of the area of land now known as Illinois. According to a 1983 paper published in the Canadian Journal of Zoology, M. enormis was discovered in a fossil bed in Mazon Creek, which inspired half of its genus name; the other half came from the Greek word for "hinge" (thairos). Based on what scientists know about arthropod behavior, M. enormis is believed to have been "actively mobile" (via Mindat.org).

As the Fossil Insect Collaborative explains, the tiny, fragile bodies of prehistoric insects don't often make it through the fossilization process. Fortunately for paleoentomologists, traces of their harder body parts and impressions of their wings do end up surviving sometimes. This was the case for M. enormis; based on "very fragmentary remains" of the insect, scientists were able to estimate its size in life. Experts say its wingspan would have reached about 22 inches, meaning that it's up there with the likes of large-winged griffinflies like M. permiana when it comes to wingspans. In fact, it's the biggest among all the members of the Palaeodictyoptera insect group.

Palaeodictyopterans have piercing, beak-like mouthparts that may have enabled them to penetrate plant tissues and suck out their juices like using a straw. Scientists call them "six-winged insects" because in addition to their main wings, they sported tiny wings near their first pair of legs (via Current Biology).

A giant honey bee from Japan

Japan's Iki Island archipelago has been a mini-goldmine of sorts for paleoentomologists. Its sedimentary rock deposits, formed beneath ancient lakes from nearly 16 million years ago, have yielded quite a few fascinating fossil insect specimens. Among these is a now-extinct species of prehistoric honey bee — one whose size rivals that of the modern-day giant honey bee found throughout southern Asia (via Featured Creatures).

In a 2006 paper published in American Museum Novitates, the world was introduced to Apis lithohermaea, a massive honey bee that lived during the Miocene era. Its remains have only ever been found in Iki Island's Chojabaru-zaki, and it's the first prehistoric giant honey bee ever found. In life, it was likely an active flyer, with forewings that measured 12 mm by 4.5 mm carrying an 18 mm-long body. Its species name is a combination of the Greek word for "stone" (lithos) and the herald of the Greek gods, Hermes (counterpart of the Roman god Mercury). Aptly enough, the discovery of this open-nesting "stone messenger" did improve humanity's knowledge about insect life during the mid-Miocene, particularly regarding theories of the region having a warm climate in this era.

A fast, flying darner from China

Many of the giant insects that populated prehistoric Earth were either similar to or located somewhere along their evolutionary tree of modern-day dragonflies. Take Epiaeschna lucida (also called Mediaeschna lucida), for instance. A 2012 article by NBC News crowned the 12-million-year-old insect as the largest insect that ever existed during the Cenozoic era, which covers the period of time from after the dinosaurs died out up to the present day.

E. lucida boasts a wingspan that clocks in at 2.6 inches (6.7 cm) long. It likely zipped and darted across the prehistoric landscape of what is now Shanwang, in China's Linqu County. It was likely carnivorous and insectivorous, with well-developed eyesight that allowed it to easily track down its prey (via Paleobiology Database). Scientists based this on the fact that dragonflies can see faster than humans and can also see all around them, and they devote four-fifths of their brain to visual processing (via Dragonfly.org). Like some of today's dragonflies, E. lucida likely reproduced by dispersing its eggs in water.

More than anything else, though, E. lucida demonstrates just how much — or how little — some things can change over the course of 20 million years.

A giant among giant ants

Despite ants' general reputation for being tiny, bigger ant species still live in the modern world. Female Dinoponera ants, for instance, are known to grow up to around 1.6 inches. According to World Atlas, they are among the largest extant ants in the world. A considerably larger type of ant lived about 44 to 49 million years ago, though — one whose scientific name means, quite plainly, "giant ant."

Titanomyrma gigantea (originally called Formicium giganteum) thrived during the Eocene period, taking up residence in the rich rainforests that enveloped the prehistoric landscape (via BBC). Based on their fossils, the male worker ants reached a maximum size of 1.2 inches. Meanwhile, the queens reached up to 2.4 inches in length, and had wings that stretched up to 5.9 inches long. Experts believe that T. gigantea lived in huge colonies.

Scientists were fortunate enough to find well-preserved specimens of these massive insect, which allowed them to learn quite a bit about how they lived. For starters, while they weren't capable of stinging, their primary method of self-defense may have involved producing formic acid, a trait they shares with some modern-day ants. Additionally, they didn't have any closing mechanisms on their crop (where they store food), leading experts to conclude that they probably consumed fresh food. They were both carnivorous and cooperative; they likely worked together in taking down and devouring animals far larger than them.

A gigantic griffinfly

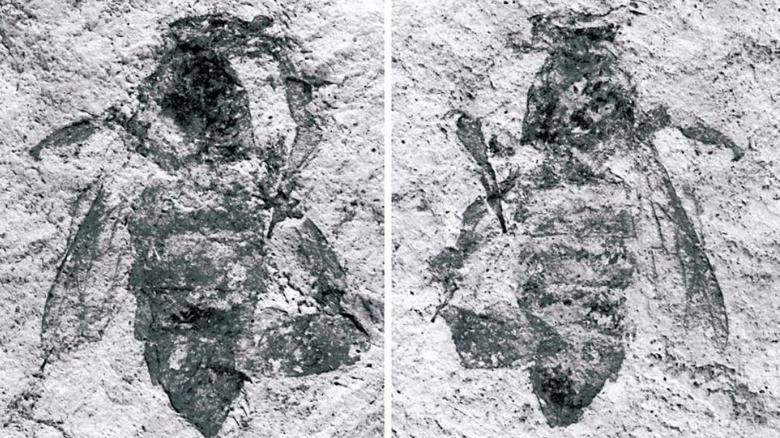

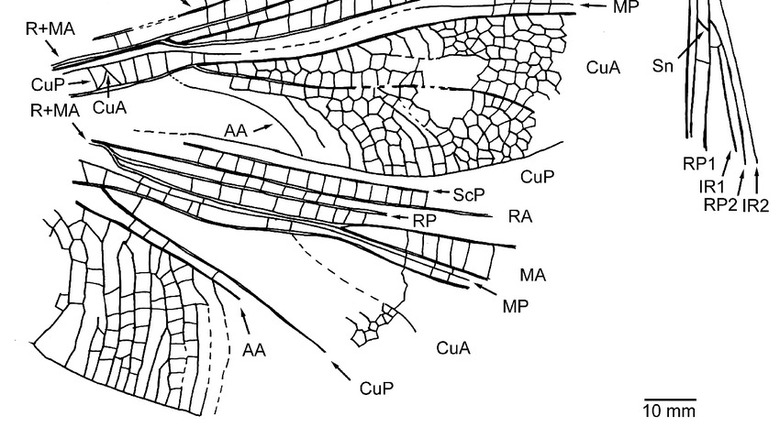

Time and time again, paleontologists have proven that even the smallest fossil fragments can say a lot about a creature that existed millions of years ago. It's even more remarkable when these paleo-detective skills are applied in entomology, like in the case of Bohemiatupus elegans. The only fossils that enabled scientists to determine details about this insect's size were mirrored fossil imprints of segments of its isolated forewing and hindwing (via Taylor & Francis Online).

B. elegans lived during the late Carboniferous period, about 315 to 307 million years ago. Its holotype specimen was unearthed in the Kladno Formation, located in Czech Republic's Radnice Basin. The experts who described B. elegans were reportedly so impressed by its "magnificent state of preservation" that they named it after the Latin word for "elegant."

In life, this particular B. elegans specimen would have had a full wingspan of about 10 inches, calculated based on its 4.5 inch forewing segment. Interestingly, the B. elegans holotype may not have even come from a full-grown insect; experts have stated that an adult B. elegans probably had a wingspan reaching an impressive 20 inches in length.

A massive pseudo-flea that sucked blood from dinosaurs

In spite of their size, fleas tend to be a massive pain in the butt for both pets and their owners. These flightless bloodsuckers have incredible jumping abilities, and can transmit a number of diseases to humans. While it may not bring much comfort to animal lovers out there, it's worth noting that 165 million years ago, the dinosaurs had a similar parasite problem.

Meet Pseudopulex, a group of flea-like arthropod parasites that made up for their limited jumping ability with... well, pretty much everything else. They were huge — about 10 times bigger than your average dog flea — and flat-bodied, which was ideal for hanging on to their gigantic food sources (via Oregon State University). They also had long claws, which made it easier for them to grab onto a snoozing dinosaur and position themselves between any protective scales or plates. Once in place, they could unleash their main weapon: a powerful, durable, and hide-piercing mouth that was the Jurassic version of a hypodermic needle (via Parasite of the Day).

Due to their similarities, it's tempting to classify Pseudopulex as the ancestors of modern-day fleas. However, experts believe that these prehistoric parasites may have just evolved in an extremely similar manner, and actually belonged to a different insect group that died out alongside their favorite prey.

A mega-sized dragonfly

The group of insects known as Meganeura includes some of the biggest bugs the world has ever seen. Among the most notable and oft-cited examples is Meganeura monyi, a griffinfly from the Late Carboniferous period that could give other king-sized critters a run for their money. In fact, some scientists call it the "iconic giant dragonfly" (via Nature).

M. monyi had an impressive wingspan of about 2.5 feet. When experts calculated the possible mass of M. monyi based on its holotype, they figured that it weighed somewhere between 3.5 to 5.3 ounces (via the Journal of Experimental Biology). Interestingly enough, this also suggests that this huge insect probably overheated a lot.

According to InfoBloom, M. monyi and other Meganeura species likely took up residence near streams, ponds, and other water formations. Fossils suggest that they were among the most fearsome insects of their time, and that they probably preyed upon smaller pond-dwellers and arthropods. They also sported a series of appendages, the purpose of which remain a mystery; experts have suggested that they may have been for hunting, mating, anchoring, or egg-laying purposes (via Furman University). However, due to their gigantic sizes, it's highly unlikely that they could dart around as quickly as today's dragonflies.

A big, bad ancient wasp

Most people have the good sense to stay away from wasps in general, due to their painful sting and fiercely territorial nature. They typically grow up to an inch long, which is just big enough for humans to notice (and avoid) them. However, a wasp three times bigger existed 53 million years ago: Ypresiosirex orthosemos, also called fossil horntail wood-wasp (via SciNews).

First found in Canada, Y. orthosemos could reach up to 3 inches in length. According to scientists, it looked a lot like its modern-day counterparts. Based on their observed similarities, experts also concluded that Y. orthosemos thrived in habitats with similar conditions to today's horntail wood-wasps; in fact, the prehistoric wasp seemed attracted to the same types of trees and flowering plants as its present-day counterparts, including hemlock, sequoia, cedar, maple, elm, and more.

Additionally, at the time when Y. orthosemos existed, the Earth's temperature was generally tropical, but the elevated area that the fossils were found in would have been cooler. This matches with what entomologists know about today's horntail wood-wasps, as they tend to populate toastier locations with "agreeable" temperatures.

The largest of the lacewings

Before butterflies showed up on the scene, there were kalligrammatids, a group of prehistoric lacewings that thrived early on in Earth's history. While they looked surprisingly similar to today's colorful butterflies, they actually went separate ways on the evolutionary tree over 300 million years ago; their shared characteristics simply demonstrate how animals from separate groups can evolve similar traits independently over time, otherwise known as convergent evolution (via Science Daily).

Among these butterfly-like creatures, the largest was a species called Makarkinia adamsi. Discovered in Brazil's Crato Formation and described in 1997, M. adamsi flitted about among the flora and fauna of the mid-Cretaceous period, approximately 122.46 to 112.6 million years ago (via FossilWorks). It had a forewing about 5.5 to 6.3 inches, which means it had the largest wings among all the net-winged insects (Neuroptera), living or extinct (via Cretaceous Research). Interestingly enough, it's also the youngest kalligrammatid.

According to scientists, M. adamsi and other kalligrammatids likely had the same feeding mechanisms as today's butterflies: elongated mouthparts that they used to suck nectar and other fluids from the plants of their era.

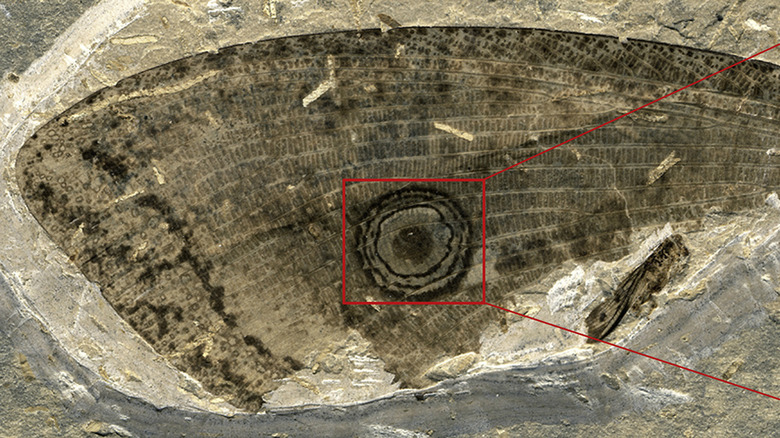

(Not) the largest mayfly ever

According to Encyclopedia.com, mayflies take their name from the month in which they become a more common sight in the Northern hemisphere, and their group's scientific name, Ephemeroptera from "ephemeral," is a reference to their brief lifespan. For almost 30 years, the scientific community accepted that an extinct insect that lived more than 300 million years ago was the largest representative of this group of short-lived winged insects.

First described in 1985, Bojophlebia prokopi was classified as a fossil stem mayfly based on an analysis of its visible characteristics. Its wingspan was estimated to have reached 18 inches in length. At the time, the conclusions about B. prokopi's true place on the insect fossil record sounded convincing enough for many authors who wrote about the species.

However, a group of scientists took another look at the holotype specimen and published their findings in a 2014 paper. They took note of multiple mistakes in B. prokopi's original description, including the absence of certain characteristics that could have placed it somewhere along the mayfly evolutionary tree. As it turned out, the errors were significant enough to warrant the possibility of reclassifying B. prokopi as a relative of a different insect group: Hydropalaeoptera. If anything, this phylogenic problem reinforces two lessons: that good science should hold up to scrutiny, and that some ancient insects were pretty darned huge.