The Untold Truth Of The French Resistance

If your only sense of occupied France in World War II comes from movies and novels, you could be forgiven for believing that practically every French person at the time was walking around with a pistol in their lunchbox, a coded message sewn into the sleeve of their coat, and a heart of steel ready to defy Gestapo torturers and the risk of the death camps for the privilege of saving France from its ruthless occupiers.

The reality, of course, is far more nuanced. By the time France fell to the Nazis, in six short weeks in summer 1940, the vast majority of its people were so focused on finding enough to eat without getting shot that resistance seemed not only ridiculously dangerous but also futile.

In many ways, they were right. Many of the people who chose to resist were isolated at best or captured, tortured, deported, and executed at worst, and as individuals, they barely had any effect on the progress of the war. Even as a broadly defined group, they were divided: Some resistors, especially Jews and refugees, were motivated to rebel by the Nazis' genocidal goals, but many others were moved by loyalty to France and were even anti-Semitic themselves.

The untold truth of the French Resistance is not of an organized and effective army of dissidents but of individuals and small units who did the best they could against incredible odds. It's messier, more violent, and more incredible than anything the movies could make up.

The beginnings of the French Resistance are not clearcut

There's a legend about how the French Resistance got started — but it's not the full story.

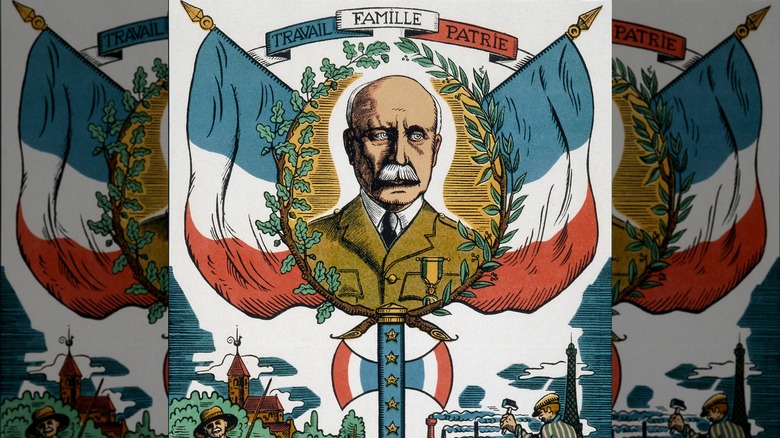

As the BBC reports, on June 12, 1940, French leadership was forced to accept that the German invasion which had started six weeks earlier had overpowered their army. France surrendered to Nazi Germany, with new prime minister Marshal Philippe Pétain signing an armistice 10 days later.

France was divided into a Nazi-occupied state in the north and a state nominally run by Pétain in the south, from Vichy, but really controlled by the Nazis. Paris was in the occupied zone. Meanwhile, thousands of French soldiers fled to Britain. Among them was General Charles de Gaulle. He took it upon himself to form a French military force to fight back against the Nazis.

On June 18, de Gaulle gave a six-minute speech from the BBC's Broadcasting House in London, in which he passionately implored the French people not to accept the Vichy government's surrender to the occupiers. He ended with, "I call upon all Frenchmen who want to remain free to listen to my voice and follow me."

De Gaulle's broadcast wasn't widely heard in France — being broadcast on British radio — but it did inspire some people to seek him out. Fortunately, de Gaulle wasn't the only French native who was horrified at the thought of surrendering to Nazi Germany. Slowly but surely, small pockets of resistance began to spring up around the country.

The French Resistance was not popular among the French

Today the French Resistance is celebrated as a symbol of France's indomitable rebellion against the powerful Nazi invaders. But in 1940, resisters were seen as radicals by many French people.

The French population at the time can be broadly divided into four groups: First, the collaborators were a not-inconsequential number of French people who supported the Nazis. This manifested in social relationships, military support, pro-Nazi militias, and anti-Semitic policies, including deporting at least 75,670 French Jews to concentration camps.

Second was the fatigued public. A year into World War II, most of the French public was too tired to fight. They were starving, as many as 90,000 of their soldiers had been killed in six weeks, and nearly 2 million more were prisoners. And it wasn't as though they disagreed with Hitler about everything: As The Guardian points out, anti-Jewish hatred and discrimination was rife in France before the Nazis arrived. Anyone who was willing to risk their own life to fight a war the French no longer saw as their own was subject to suspicion.

Third, the passive resisters: people who read anti-Nazi newspapers but didn't take part in resistance activities like sabotage and feeding information to Allied forces. All that leaves the people who came to be known as the French Resistance. Estimates as to how much of the French population actually took part in the Resistance come in at about 2%, the BBC reports.

The French Resistance started out small and disorganized

Imagine the chaos of France in 1940. The government has surrendered to the Nazis, a brutal and well-organized regime known for its torture-happy secret police and for executing dissidents. Many families have already lost loved ones to the battlefield. The last destructive war fought on French soil had happened within living memory. And the Nazis are starving the French.

Being a resister was impractical and incredibly dangerous. You risked torture and almost certain death if you were caught or betrayed. And there wasn't much you could do as one person: Unless you were already a member of an anti-Nazi group (also very dangerous), first you had to find other people who shared your desire to fight back.

So it's not surprising that the French Resistance started out as a group of small, unconnected, disorganized cells, who had their own — often conflicting — motives for fighting. As the Daily Beast notes, resisters came from all walks of life, from students to soldiers to farm laborers, and every part of the political spectrum. For example, some specifically loathed the Nazi ideology, whereas others felt a surge of French nationalism.

Back in Britain, de Gaulle realized that a divided Resistance effort could not achieve his grand plans to retake France. In 1942, he tasked Resistance leader Jean Moulin with uniting the eight main groups under the banner Conseil National de la Résistance (CNR). This theoretically made it easier to coordinate strategies and communicate with the Allies.

Many members of the French Resistance were not French — and were Jewish

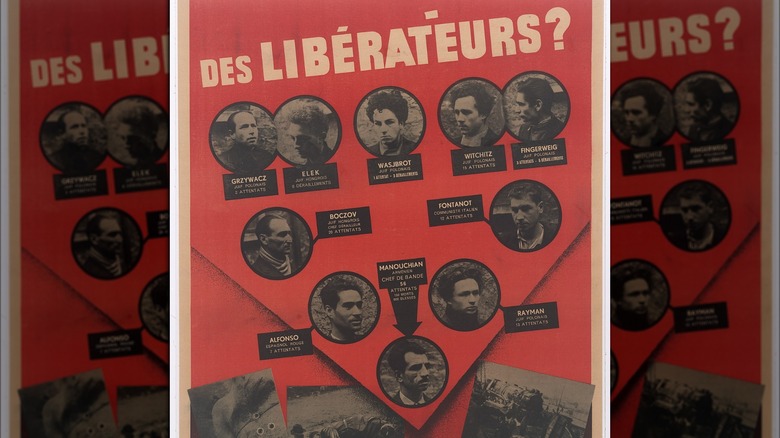

If the general French public believed that keeping its collective head down or even supporting the Nazis was the path to survival, for many people in France, collusion with the new regime meant certain death. As such, many founding members of the French Resistance were Communists, immigrants, and Jews — and often all three.

Although only approximately 1% of France's population in 1940 was Jewish, it's estimated that Jews made up as much as 20% of the Resistance — although given that Resistance groups did not exactly keep meticulous lists of all their members, it's hard to say for sure.

These groups had the most cause to fight the Nazis, who were already persecuting and executing people like them in concentration camps. And since they were widely distrusted among the French, too, it wasn't as though they had to worry about sacrificing friendly relations with their neighbors. The Nazis even used the French public's resentment and hatred of these groups in propaganda intended to dissuade them from joining Resistance groups, the LA Times reports.

Some Communists were initially reluctant to side against the Nazis, thanks to the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact between Nazi Germany and the Communist Soviets. But when Hitler invaded the USSR on June 22, 1941, French Communists were more than ready to join the Resistance. With structures already in place, groups affiliated with the Communist Party provided much-needed organization in the Resistance's early days.

Children and teenagers contributed to the French Resistance

The Resistance required a rebellious spirit and a readiness to rush into danger, so perhaps it's not surprising — although no less admirable — that many members were teenagers and even children.

For example, Charles de Gaulle's niece Geneviève de Gaulle was 19 when she joined teenage-led Parisian group Défense de la France. As The Guardian reports, they published a newspaper about the atrocities committed by the Nazis and the Vichy government. In 1943, Geneviève was arrested: She survived Ravensbrück women's concentration camp.

Another teenager, Adolfo Kaminsky, became an in-demand forger aged 18 in 1944, after the Resistance provided his family — who were Jewish — with fake papers. He could forge 30 papers an hour, he told The New York Times, but the pressure was enormous. One mistake could mean the person using the papers was caught, deported, or executed.

Young children were helpful to the Resistance: The Gestapo was less likely to suspect them, so they could move messages, packages, and weapons. In 2020, France honored six-year-old Marcel Pinte, son of Resistance leader Eugene Pinte. Marcel ran messages for the Resistance and was killed in August 1944 when a parachute drop of armaments went off by accident. The night of his funeral saw Eugene lead the local Resistance movement in liberating Limoges. These are just three examples of the many young people who put their short lives on the line to fight the Nazis.

French Resistance groups used many different tactics

Just as there was not one French Resistance network, there were many different ways groups chose to resist. Some directly attacked soldiers. Some gathered and passed intelligence to the Allies and the Free French. Some published media drawing attention to the atrocities perpetrated by the Vichy government and the Nazis. And some rescued as many people from deportation to concentration camps as they could.

Resistance groups rarely had enough weapons to make violence against Nazi soldiers worth their while. The resisters were usually outgunned, and the Nazis often retaliated against civilians. However, the militant groups that formed in the countryside — known as Maquis — did occasionally organize to attack the rear of Nazi convoys.

Groups whose main mission was to directly fight the Nazis mainly relied on sabotage. When the Germans started to commandeer factories and railroads, the Resistance focused on destroying these assets, preventing the Germans from moving troops and supplies. Phone and power lines, trains, and munitions and fuel depots also became common targets leading up to D-Day.

Meanwhile, other groups focused on smuggling Jews and other at-risk people to safety, especially children. According to The New York Times, France's Jewish resistance groups saved between 7,000 and 10,000 children. One of many courageous examples was a Paris-based Polish Jewish resistance cell called Solidarity. They ran secret missions that saved an estimated 14,000 Jews from the Vichy government's most notorious roundup in July 1942, when 13,000 French Jews were captured and deported.

British secret services supported the French Resistance

When France fell to the Nazis in June 1940, British prime minister Winston Churchill vowed to provide assistance to anyone in the country who wanted to resist. Thus, the Special Operations Executive (SOE) was born that July, complete with a special unit — F Section — dedicated to supporting resistance in France.

Agents were recruited in Britain, but many came from elsewhere, including Poland, Romania, New Zealand, and America. They parachuted into France, bringing food, weapons, sabotage and combat training, and information about the Allies' plans. In return, they gathered intelligence from the resisters.

Some SOE agents worked undercover in France for long periods of time. For example, F Section radio operator Noor Inayat Khan spent nearly four months working in secret in Paris — the last surviving SOE radio operator in the city, where just possessing a wireless radio meant a death sentence. She was ultimately betrayed, arrested and tortured, and executed in Dachau concentration camp. Khan's story is just one of many similar examples of agents' courageous attempts to fuel the resistance.

As we've seen, the French Resistance was not monolithic — unless you ask Charles de Gaulle. Still in London, De Gaulle was running his own resistance movement, the Free French, under SOE's RF Section, and saw F Section as competition. After the war, he attempted to undermine the British intelligence agencies' contributions to French liberation. According to The Telegraph, he even told one SOE agent, "We don't need you here. ... go home."

The Nazis tried to hunt down members of the French Resistance

The Nazis didn't take any form of resistance lightly. From the start of their occupation of France, they arrested, deported, and executed anyone seen to be fighting back or disagreeing with their regime.

Resisters were typically put through a phony military trial by the German army before being sentenced to death by firing squad or deported to a German prison or concentration camp. Torture was common. The purpose was not only to punish active resisters but to dissuade anyone else considering fighting against the Nazis.

One of the most notorious Gestapo agents, Klaus Barbie, was nicknamed the Butcher of Lyon because of his sadistic practices. He deported an estimated 7,500 Jews and resisters (and don't forget Jewish resisters) to camps and executed around 4,000 others. He relished opportunities to personally torture members of the Resistance.

After the war, Barbie was smuggled out of Germany by the U.S. and worked for American intelligence agencies in South America. He was eventually extradited to France to stand trial for crimes against humanity. In 1987, several torture survivors testified against him in court, the Associated Press reported. He was sentenced to spend the rest of his life in French prison.

If the Nazis couldn't find the people responsible for acts of resistance (such as sabotage or the murders of German troops), they carried out revenge arrests, deportations, and executions of civilians who happened to be nearby or who were already in custody.

One of the earliest organized resistance groups started in a museum

Weeks after the Nazis conquered France, and partly inspired by de Gaulle's radio plea, a group of curators, professors, librarians and academics affiliated with Paris' Musée de l'Homme and Musée National des Arts et des Traditions Populaires formed one of the first organized resistance groups.

Early members included Boris Vildé, Yvonne Oddon, Anatole Lewitsky and Agnès Humbert. The director of the Musée de l'Homme, Paul Rivet, facilitated their work, letting them use the museum's resources and the building as a base. He also used his position to collect and pass intelligence to the Allies and publicly criticized Marshal Pétain.

The group's acts of resistance started small but were no less subversive. According to The Guardian, they chalked "Vive de Gaulle" on building walls and printed and distributed an anti-Nazi and anti-Vichy newspaper, Résistance. From there, they began sending information to British intelligence, rescuing stranded British airmen, and smuggling refugees out of France.

By late 1940, the Musée de l'Homme group had about 100 members. It teamed up with two other resistance groups, with about 130 members between them. As the group's member count and reach grew, so did the risks. In February 1941, they were betrayed. Rivet escaped, but after spending a year in prison, Vildé and Lewitsky were executed, along with five others, on February 23, 1942. The women were deported to concentration camps: Oddon survived Ravensbrück.

Some members of the French Resistance became famous

Estimates have put membership of the French Resistance anywhere from 75,000 to 400,000. But only a few of that number are famous.

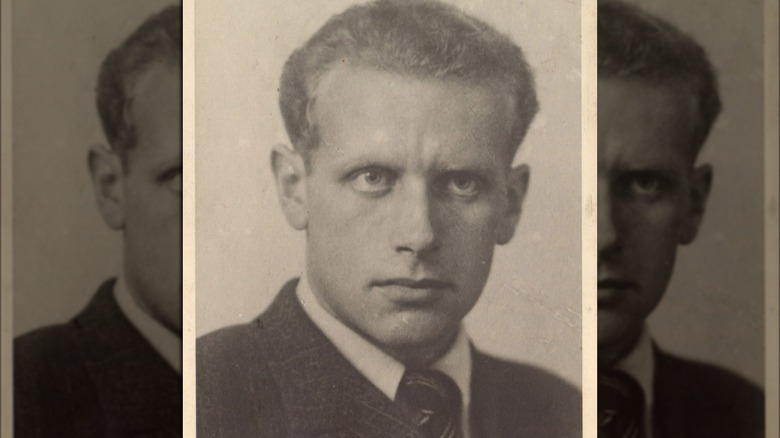

As the BBC reports, left-wing French civil servant Jean Moulin (left above) had already been imprisoned and tortured by the Gestapo when he set up a Resistance movement with de Gaulle's blessing in January 1942. In May 1943, Moulin established the Conseil National de la Résistance (CNR), uniting disparate groups into an organized effort spearheaded by de Gaulle's Free French movement. Just a month later, he was betrayed and arrested. He died on a train to Germany, from wounds inflicted by notorious torturer Klaus Barbie.

American-born Josephine Baker (right above) emigrated to France in 1925 (partly to escape segregation), and she became a nightclub singer, dancer, and all-round superstar. According to History, When the Nazis invaded, Baker added spy for the Resistance to her resume. She traveled widely, even bringing extra luggage and her many pets to ensure she attracted attention. Surely someone that visible couldn't be involved in subterfuge! But the information Baker gathered was invisible: As she charmed her way around parties filled with high-level military and civil officials across Europe, her assistant Jacques Abtey — actually head of the French military's secret service — recorded everything they said in invisible ink on her sheet music.

One French Resistance member found fame for something outside his wartime work. Mime Marcel Marceau, his brother, and his cousin all helped smuggle Jewish children out of France to neutral Switzerland.

The French Resistance came into its own for D-Day

As the Allied forces prepared to invade France and retake it from the Nazis, the Resistance got organized. In the week leading up to the Normandy landings, those groups working with British SOE's F Section were told to sabotage railroads using explosives and nonviolent methods like strikes and go-slows. This slowed the Germans' response to the invasion. The Nazis actually recognized the BBC radio broadcast alerting the Resistance to D-Day as a code, but they misunderstood the message's meaning and failed to react.

Meanwhile, Resistance groups loyal exclusively to de Gaulle did not take part in the Normandy landings, because de Gaulle felt that the other Allied leaders had excluded him from the planning of these attacks. Instead, de Gaulle's Free French army — which included forces from French colonies that had not been occupied – landed at Provence, on the southern coast. As in the north, Resistance fighters helped slow down and distract the German army. Together, they liberated the territory in less than two weeks and eventually met up with the forces who had landed at Normandy.

As thrilling as the possibility of liberation was, it was also dangerous. The Nazis massacred entire villages in response to Allied victories and specific Resistance activity. The most infamous incident took place four days after D-Day, on June 10, 1944, in Oradour-sur-Glane, near Limoges: 642 people — including 247 children — were shot and burned to death, The Guardian reports. Other villages suffered similar fates.

The French Resistance helped liberate Paris

As the Allies pushed the Nazis out of France, more people were emboldened to resist the occupiers. Originally, Allied supreme commander Dwight Eisenhower planned to bypass Paris, fearing delays that would give the Germans time to regroup. But Parisians weren't waiting for permission to rise up.

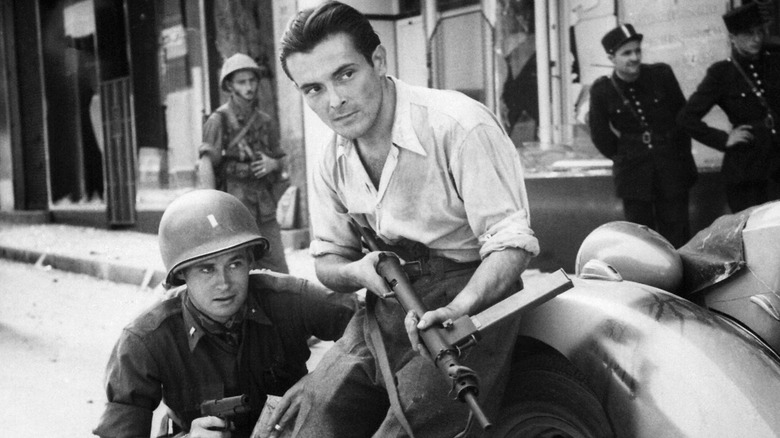

On August 10, 1944, railroad workers went on strike, followed by the police five days later. After D-Day, most of the Resistance had united and rebranded as the French Forces of the Interior (FFI). Finally, it had become a reasonably well-organized militia (although an underequipped one, per the BBC), headquartered in the historic Place de I'Hôtel de Ville. Starting on August 19, the FFI, the police, and the civilians took the battle to the streets of Paris. They constructed barricades — a classic French street-fighting tactic — and shot Nazi soldiers with any guns they could find.

De Gaulle and Free French general Philippe Leclerc persuaded Eisenhower to detour to the capital to support the uprising. On the night of August 24, Leclerc and the Free French army, flanked by motorbike-riding FFI members and with American support, rolled into Paris, just over four years since the Nazis had captured the city.

The Germans surrendered on August 25, shortly before de Gaulle arrived. Around 1,000 Resistance fighters, 600 civilians, and 156 French soldiers were killed in the Battle of Paris. But compared to the 3,000 German losses, it wasn't the bloodbath the Allies had feared — not for the French, at least.

The legacy of the French Resistance was rewritten after the war

Postwar France was, frankly, a mess. An estimated 77,000 Jews had been deported from France to concentration camps by the Vichy government, along with suspected Resistance members, Communists, and anyone else the Nazis wished to exterminate. Around 212,000 military personnel were dead, and nearly 2 million were prisoners of war. Approximately 260,000 civilians had been killed – 70,000 by the Allies.

France was forced to confront its capitulation to the Nazis, and the role its government and civilians had played in advancing war crimes. Collaborators bore the brunt of this need for revenge and closure: They were humiliated, beaten, and executed – in some cases by other former collaborators, TIME reports.

When de Gaulle became provisional leader of France after liberation, he rewrote the narrative of the war, hoping to reinvigorate French pride. He painted the French Resistance — the parts that were loyal to him — as a well-organized, cohesive, and large movement. In de Gaulle's retelling, he was the beloved figurehead, and the movement became less Communist, less foreign, less Jewish, and less female. For example, of the 1,038 resistors that de Gaulle formally recognized for their heroism, only six were women, according to The New York Times.

The French Resistance was never a single fighting force, united against the Nazis. It was thousands of people risking torture, deportation, and death — often with very little to show for it — because, for whatever reason, they understood that resisting an overwhelmingly powerful enemy was the right thing to do.