The Untold Truth Of The Eucharist

The Eucharist, according to EWTN, literally means "thanksgiving" in Greek and has several interrelated meanings. It technically refers to the second half of Orthodox, Catholic, and Oriental Orthodox liturgy. In Western Rite Catholicism, this is known as the liturgy of the Eucharist (as opposed to the liturgy of the word), in which the bread and wine are consecrated into the "body, blood, soul, and divinity" of Christ. (They stop being bread and wine.) Eastern Catholics and Orthodox Christians refer to it as the liturgy of sacrifice, which captures the reasoning behind the thanksgiving: Christ's sacrifice on the cross for the forgiveness of the sins of humanity.

The Eucharist in Catholic and Orthdox belief is not merely a representation of Christ's sacrifice or a re-enactment of it. Defining it as such would mean that it is purely symbolic. Rather, it is understood as a "re-presentation" of the Last Supper and Christ's sacrifice upon the cross. The term "Eucharist" is also used to refer to the communion species (i.e. consecrated bread and wine). Hence, in Catholicism, when it is said that one must be ready to receive the Eucharist, it is referring to the Body and Blood.

The concept of the Eucharist and the practices around it are grounded in pre-Christian Jewish traditions which are recorded in the Old Testament, and which Christians interpret to foretell the eventual coming of Christ to this world. This is the untold truth of the Eucharist.

What happens during the consecration?

During the liturgy of the Eucharist, the bread and wine become the literal Body and Blood of Christ, but the priest himself does not transmute them. Instead, Canon 1548 of the Catechism states that the priest acts "in persona Christi" (literally "in the person of Christ"). He represents the sacred person of Christ himself, who is believed to be leading the congregation as both priest and sacrificial victim in the Eucharistic feast.

Per Matthew 10:1, Christ gave his apostles the power to cast out demons and cure people in his name. So, when a priest repeats Christ's Words of Consecration ("this is my Body...") and raises the host, the bread and wine become the Body and Blood just like during the Last Supper more than 2,000 years ago, a process called transubstantiation.

The Orthodox tradition uses different language to describe the change into the Body and Blood. Because Orthodoxy's liturgical language is Greek, the change is defined as a metamorphosis, while the priest operates as an icon of Christ. In Eastern Christianity, icons are images. According to the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America, "image" in Orthodoxy refers to something that bears the qualities of the divine original but isn't the same thing. Therefore, humans are not God but are created in his image. In the same way, the Orthodox priest acts as Christ's image, allowing the bread and wine to become Body and Blood during liturgy. The exact mechanism, however, is considered a mystery.

For the doubters: The Eucharist can prove itself

Belief in the Eucharist as the Body and Blood of Christ is at an all-time low in the United States, with a mere 31% of Catholics professing belief in this theology. For the doubters, however, Catholics believe in Eucharistic miracles to convince doubters of the sacrament's veracity.

The Vatican recognizes 160 Eucharistic miracles. Among the most famous (but virtually unknown to the average Christian) is the eighth-century miracle at Lanciano. A monk celebrating mass at a church in Abruzzo in south-central Italy had doubts regarding the yet-undefined dogma of transubstantiation. According to ZENIT, when the skeptical monk pronounced the Words of Consecration, the bread suddenly changed into human flesh and the wine coagulated into globules in the chalice, clearing all doubts as to their true nature following the consecration. A similar miracle occurred at Bolsena, when a Bohemian priest saw the hosts bleed out onto the cloth.

In the East, the Russian Orthodox Church maintains a protocol for Eucharistic miracles during a liturgy. Should the bread and wine change their appearance to flesh and blood during the consecration, it is considered a miracle. However, the change is meant to convince those with doubts, and as such the hosts in question are interestingly not considered the Body and Blood. Once this happens, the priest should consecrate a new set of hosts and distribute those, presumably having had all his doubts cleared. It's confusing, even to other Christians, but fascinating nevertheless.

Eucharistic preparation

The Eucharist is the "sacrament of sacraments," a view echoed throughout the traditional Christian triad of Orthodoxy, Catholicism, and Oriental Orthodoxy. Receiving Jesus is a momentous occasion. Among American Catholics, communion has become part of "the motions," but in the past, it was an occasion worthy enough to be mentioned in chronicles due to the intense preparation and the rarity of reception.

Louis IX of France (aka Saint Louis) is considered one of the paragons of Eucharistic preparation in the Catholic Church. Despite being king of one of Europe's most important kingdoms, according to Catholic Exchange, Louis IX found time to pray constantly during the day, attend daily mass, and ensure he was fully prepared to receive the Eucharist. He and his wife Margaret of Provence observed sexual abstinence on the day before receiving the Eucharist and the day after. If he stayed with his wife during abstinence periods, such as during Lent or Advent, the king would leave her and pace around the room until his desires were gone, per the Franciscan Order of Australia.

Louis IX never committed a mortal sin and went to great lengths to keep his soul clean. Nevertheless, Ferdinand Holbock notes in his book "Married Saints and Blesseds" that Louis only received the Eucharist six times per year, which was still more than most, who only received it once a year or once in a lifetime. His devotion to the liturgy and the Eucharist epitomized the importance of the sacrament in Catholic life, and for his devotion, the king was declared a saint and a model of Christian kingship.

Christians have died for the Eucharist

Since the Eucharist is so sacred, it naturally follows that it should be protected from harm and desecration, even to the point of death. After all, it is the Body of Christ. This belief has been around since the early days of Christianity, best encapsulated in the martyrdom of St. Tarcisius, a third-century Roman martyr who risked his life to bring consecrated hosts to Christians languishing in prison. It would be his last act.

According to EWTN, Catholic priests at the time were often recognized when delivering hosts to secret masses and to prisoners condemned to die under Roman persecution. St. Tarcisius, as an acolyte, could blend in more easily, so he was entrusted with the delivery of the hosts. As he was arriving in Rome on the Appian Way, tradition says that St. Tarcisius ran into a group of pagans who demanded to know what he was carrying. The saint refused to allow the hosts to be defiled by pagans (i.e. he "refused to cast pearls before the swine") and ignored them. His assailants then beat him to death, but miraculously, they could find no trace of the Blessed Sacraments he had been carrying.

Attacks against churches and thefts of consecrated hosts continue to occur today, but Western Catholics don't often show the same willingness to protect the Eucharist as their Christian brethren further east, where, as recently as 2014, a modern-day St. Tarcisius risked his life to rescue consecrated hosts and lived to tell the tale.

Standing firm against ISIS

It is unsurprising that the most recent Eucharistic hero would come from the war-torn country of Iraq. Despite centuries of Muslim persecution, Iraq and Syria's forgotten but vibrant Christian communities, whether Catholic, Orthodox, Syriac, or Armenian, have clung steadfastly to their faith and to their sacraments. Following the rise of ISIS in 2014, they again faced the choice of conversion to Islam or submission to horrific torture, sex slavery, and death.

For Middle Eastern Christians, their faith was their pillar during the horrific ISIS onslaught. Pope Francis recognized this and, according to Agenzia Fides, declared Middle Eastern Christians "witnesses and guardians of the faith." One man certainly deserves this title, for saving the most precious item in his church, the Blessed Sacrament, from falling into ISIS' hands.

According to the Catholic Register, the Iraqi village of Karamlesh was about to fall to ISIS. The inhabitants had all fled, with the exception of some priests and one man named Martin Baani. As ISIS forces were entering the village, Baani and the priests went into the church and cleared out the consecrated hosts. They got in a car and fled, escaping with the most precious objects in the church — the Body of Christ. Baani would later become a priest in Iraqi Kurdistan and continues to minister to Christian refugees as he attempts to keep Iraq's 2,000-year old Christian community intact. His story illustrates the value of the Eucharist to all Christians who believe in it, but especially those who find themselves persecuted with nowhere else to turn.

The Eucharist at War

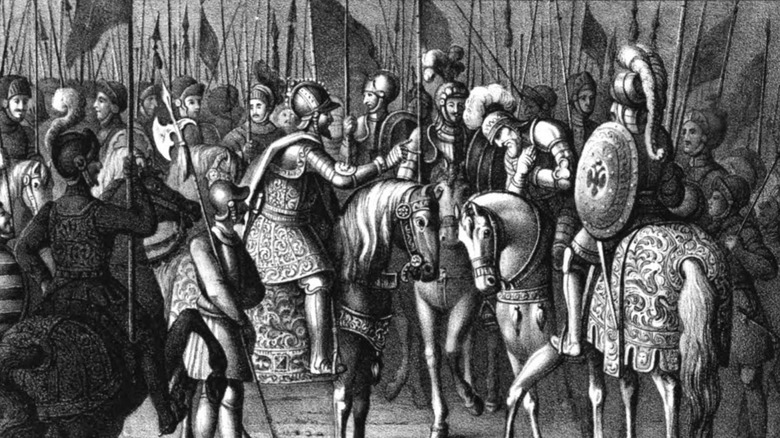

The Eucharist has inspired fervent devotion to the point of martyrdom, so it should be no surprise that it has caused wars, too. Since 1962, lay Catholics have received both Body and Blood. Before the Second Vatican Council, however, the laity received the Body. In 1415, a disagreement on this very issue resulted in a series of bloody wars between Bohemian Hussite heretics and the Holy Roman Empire.

The Hussites, per the Catholic Encyclopedia, are referred to as such after their founder Jan Huss. In 1420, the Hussites issued the Four Articles of Prague, outlining where they differed with the Catholic Church. The second article called for the reception of both species of communion by the laity, rather than just the Body, and became the hallmark of Hussitism.

As the Hussites gained political power, Bohemia became a stage for Imperial forces, crusaders, and Hussites to battle it out on the kingdom's blood-soaked fields. Eventually, the moderate Hussites, who are known as Calixtines due to their dedication to the aforementioned second Article of Prague, defeated the radical Taborites and reached an agreement with the Catholic Church to form a rite called Utraquism. Although it was not merely the Eucharist that caused the fighting, the centrality of it certainly attested to its power among the faithful.

The Eucharist for other Christian faiths

The Eucharist is a sign of unity, so its reception requires communicants to be members of their respective churches. Most Catholics, however, are unaware that the Church does provide the possibility for non-Catholics to receive under certain circumstances.

According to Canon 844 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Christians that share the Catholic belief in the Real Presence can receive Catholic communion as long as they have properly prepared themselves to do so. Members of "Eastern Churches" are permitted to take part under these rules, although they are encouraged to respect the discipline of their own churches and prohibitions on taking communion outside their own liturgies.

While Catholics grant a great degree of latitude towards non-Catholic Eastern Christians, the permissions do not apply in reverse. Orthodox churches deny all non-Orthodox communion, and Orthodox Christians are forbidden to receive communion in any non-Orthodox churches. Instead, they may take non-consecrated bread called the antidoron. Protestants are barred from communion in Catholic and Orthodox churches, but this was not always the case. In the Renaissance, Protestants were allowed to receive Catholic communion even after they had been labeled as heretics.

Charles V and the Protestants

During the Reformation, Martin Luther's Protestant followers were not acknowledged as a separate church. According to Musée Protestant, Holy Roman emperor Charles V instead sought to bring Protestants back into the Catholic Church and reclaim confiscated church property. After the emperor refused to accept the Lutheran Confession of Augsburg, the Protestant princes formed the Schmalkaldic League to oppose Charles V in concert with, ironically, Catholic France.

As Charles attempted to snuff Protestantism out before it could spread, the Catholic Church initiated the Counter-Reformation with the Council of Trent in 1545. The Protestant representatives were ordered to appear as well, but they refused to attend as fissures developed in the Protestant alliance. Seeing an opportunity, Charles attacked the Lutherans and defeated them at Mühlberg in 1547.

The defeat forced the Protestants to negotiate, but the Catholic Church incredibly made concessions and allowed them to remain within the bounds of communion with Rome. In return for accepting Rome's authority, the Protestants were allowed to take communion in both kinds (as the Hussites had done), and their clergy were allowed to marry. Most incredibly, despite being labeled as heretics, they were still admitted to Catholic communion.

This arrangement did not last long. The Lutherans defeated Charles in 1552 and forced him back to the negotiating table. The cuius regio, eius religio was adopted and recognized the Lutheran Church as official in the areas whose rulers followed it. Thus ended the short, five-year practice of Catholic-Protestant intercommunion.

Eucharist through poetry

Why were Protestants forbidden from taking communion when, for a short time, they had been allowed? The answer lies in the attitude toward the Body and Blood. According to Patheos, Martin Luther and several subsequent reformers viewed the Eucharist symbolically, rejecting transubstantiation. In England, which had swung between Catholicism and Protestantism under the Tudors, things were slightly more complicated. Queen Elizabeth I gave her own opinions on the matter, rejecting transubstantiation and Catholicism through poetry.

While in prison before she became queen, Elizabeth penned a poem about transubstantiation and the Eucharist called "A Meditiation how to Discern the Lords Body in the Blessed Sacrament." A stanza reads, "AND if Mens Fingers cannot make the Wheat,/ Which makes the Sacramental Bread we eat;/ What Art of Transubstantiation can/ Make God of Wafers, who of Dust made Man?"

This stanza illustrates Lady Elizabeth's confusion with the concept of transubstantiation. How could a man who could not make his own bread or wine make the Body and Blood of Christ? This would show when she became queen in her own private liturgies.

Historian Alice Hunt writes in "Tudor Queenship" that Elizabeth would order chaplains at her private liturgies to skip the elevation and consecration of the host, as is done in Roman Catholic liturgies. In doing so, Elizabeth implicitly rejected transubstantiation, going as far as to leave the liturgy early when the pastor refused to obey her orders.

Let the children come to me!

Among the rules for receiving Catholic communion is that the communicant must have obtained the age of reason (~age 7) and made first communion. This, at least, is the case for Western Rite Catholics. Per Ascension Press, the Catholic Church is really made of 24 different churches which have their own communion practices.

According to the Presentation of Our Lord Ukrainian Catholic Church, Eastern Catholics and Orthodox Christians allow people to take communion from infancy, a practice that surprises many Western Rite Catholics when they visit Greek Catholic and other Eastern churches. This is because unlike the Roman Church, which administers baptism, communion, and confirmation separately, Eastern churches administer all three sacraments to newborns simultaneously, according to The Byzantine Catholic Archeparchy of Pittsburgh.

The infant communion is just the beginning of the differences between Eastern and Western Christians. While Western Catholics receive the Body and Blood, Eastern Christians receive the host with a spoon, an issue that has caused considerable controversy in the COVID-19 era. The priest mixes the Body and Blood together in a chalice and feeds each communicant, from babies to elderly, a cube of Body soaked in Blood, as if a parent is feeding his child. This method of distribution is meant to prevent spillage of the Eucharist, but it also exemplifies the relationship between God as the father of his faithful, a beautiful image, no doubt.

The elephant in the room: Politicians and the refusal of communion

For many, the Eucharist is not merely a symbol — it is a declaration of faith and unity, so reception by politicians who publicly reject church teachings has created controversy. The secular and Catholic media have weighed in, accusing each other of "weaponizing the Eucharist." But what does the church actually teach on this?

First and foremost, as mandated by Canon 915, priests must refuse communion to anyone publicly known to be in a state of mortal sin. This would include the civilly divorced in another relationship, public sinners, and public figures (aka politicians) who advocate abortion, gay marriage, or a raft of other policies seen as sinful. Canon 915 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church explicitly states that those who persist in "manifest [i.e. public] grave sin" cannot be admitted to communion, and the rules apply to politicians as they do to anyone else.

Catholic politicians such as U.S. House speaker Nancy Pelosi, President Joe Biden, and Governor Kathleen Sibelius, despite their self-categorization as Catholics, objectively cannot receive communion. Their public promotion of abortion automatically disqualifies them. Since the commission of a mortal sin is a one-way ticket to hell, denial is an act of mercy. Hence, the South Carolina priest who denied Biden communion in 2019 acted correctly according to the church's rules and thus avoided committing a sin himself.