The Untold Truth Of The Nativity Of Jesus

The commercial, secularized version of Christmas is lots of fun, with Santa, Frosty, Rudolph, and candy canes, but at the heart of it, Christmas is a religious holiday meant to commemorate the birth of Jesus. The centerpiece of many religious Christmas celebrations is often a Nativity scene, a tableau representing the image of Mary and Joseph with the infant Christ in a manger, usually surrounded by livestock, shepherds, three wise men, and angels. It's an image known around the world thanks to the pervasiveness of Christmas culture.

But what does the Bible actually say about the events of the birth of Jesus? Surprisingly little, as the narrative only appears in one Gospel, which you hear recited by Linus every year. The good news is, tradition, archeology, and science have gone a long way to fill in some of the gaps left in the biblical narrative. Here's what you don't know about the nativity of Jesus.

Jesus probably wasn't born on Christmas

Because of the fact the birth of Jesus is celebrated each year on December 25, and the major divide in how we date periods of history as "Before Christ" or "In the Year of Our Lord," it would be really easy to assume the historical Jesus was born on December 25 in the year 1 AD. However, despite the fact the Christian church has been celebrating Christmas on December 25 since the fourth century, no one really knows for sure when Jesus was born, and the Bible doesn't give that information. As Live Science points out, many people believe Jesus was born in the spring due to the description of the shepherds watching their flocks by night, something that likely wouldn't happen in winter. The December date is generally understood as having been chosen to provide an alternative to pagan winter festivals like Saturnalia.

But while the month and day of Jesus' birth are a little fuzzy, he definitely wasn't born in 1 AD. One of the major players in the Christmas story is the Judaean tetrarch Herod the Great, who died around 4 BC. As such, in order for him to put out a hit on a baby, that baby would have had to have been born between 6 BC and 4 BC at the latest. That said, historians argue about Herod's death, too, so no one really knows anything.

Augustus' census makes no sense

The only account of Jesus' birth in the New Testament comes in the Gospel of Luke, which says Mary and Joseph had to travel to Bethlehem because of a census being taken by the Roman emperor Augustus, held while Quirinius was the governor of Syria. As Bible.org explains, however, this causes a problem of chronology. For one thing, the first known Roman census of Palestine occurred in 6 or 7 AD, and Luke specifies this was the first census made while Quirinius was governor, but secondly, there is no evidence Quirinius' time in office as governor of Syria overlapped with Herod the Great's life. Since the details of the timing don't overlap very well, it is a bit of a pickle to try to nail down when exactly the circumstances of Jesus' birth occurred, though there are those who propose something along the lines of Luke meaning "before the census when Quirinius was governor" instead of "the first census."

You might also wonder about the detail of Mary and Joseph having to travel from their home to their ancestral homes to be counted. The book God, Reason, and the Evangelicals argues such a practice did not, in fact, happen, and that taxes were carried out on a local level. Furthermore, there is no record at all of Luke's census among the Romans' substantial records of such things.

Jesus probably wasn't born in a stable

The image known as a "Nativity scene" is well-known to Christians and probably to most Americans or Europeans regardless of religious origin: Mary and Joseph kneeling next to a feeding trough with the infant Jesus inside it while donkeys and cows and sheep stand around, because this family is in their space. The story is famous, too: there was no room in the inn in Bethlehem, so the Holy Family had to stay in the stable. Everyone knows that. Well, some modern scholars argue this iconic image isn't completely accurate. Theologian Ian Paul told the Guardian Jesus wasn't born in a stable at all, nor were Mary and Joseph refused room at an inn.

Paul claims the Greek word traditionally translated as "inn" actually referred to a reception room in a private house, which was presumably full of other relatives. (Mary and Joseph were going to their ancestral home, right? They would have relatives there.) Palestinian homes at the time would have had a room indoors on a lower floor where animals were kept at night. And so Jesus would not have been–as traditionally depicted–born in a separate outbuilding for animals, but an indoor room on the lower floor of a peasant home. In such a case, there would still have been a manger for Jesus to be laid in, which the Gospel of Luke does specify.

The Star of Bethlehem probably wasn't a star

For many Christians, the literal truth of the Bible is an important aspect of their faith, and so as scientific knowledge increases over time, it has become more common to see some scholars attempt to provide scientific explanations for miraculous phenomena in the Bible, such as the parting of the Red Sea or God extending the length of a day so Joshua could lead the Israelites to victory. The famed Star of Bethlehem is no exception. EarthSky records a number of different possible explanations for the bright star that led the Magi from the East to the location of the child Jesus.

For the most part, these explanations include the Star being something other than a literal star, but that would still appear star-like in pre-astronomy days. For example, it could have been a comet, a number of which are mentioned in astronomical records kept by the Chinese in those days. More promising is a Chinese record of a supernova in the spring of 5 BC, right in the sweet spot for Jesus' potential real birth date. Others argue, however, that it wasn't a star, but rather a planet. Or, more specifically, the conjunction of more than one planet. There are records of conjunctions between Jupiter, Saturn, and Mars in the time period of 6 to 5 BC, so if you're looking for noteworthy astronomical phenomena in that time period, that's a contender.

Time stood still when Jesus was born

The Gospel of Luke tells of Jesus' birth in the manger, with the shepherds and angels, while the Gospel of Matthew tells about the Magi from the East coming to present him with kingly gifts, but otherwise the Bible is silent on the details of the birth of the Lord. The early church was just more concerned with Jesus' Second Coming than his first one. However, as time went on, narratives began popping up that filled in some of the frustratingly absent details from the canonical Gospels. These apocryphal texts are generally known as Infancy Gospels, and one of the most notable ones is the Infancy Gospel of James, also known as the Protevangelium.

While much of the Protevangelium is about the birth and childhood of Mary, there is one striking scene regarding the Nativity of Jesus when Mary is about to give birth (notably in a cave, not a stable) and she sends Joseph out to seek a midwife to aid in the delivery. From a first-person perspective, Joseph describes walking through the night as all of nature has literally frozen in place. He saw birds paused in their flight midair, people eating frozen mid-chew, and flowing river water stopped mid-splash. Just as quickly, time resumes its normal flow and Joseph finds a midwife. Not that Mary needs one, as the baby Jesus teleports out of her womb in an explosion of light.

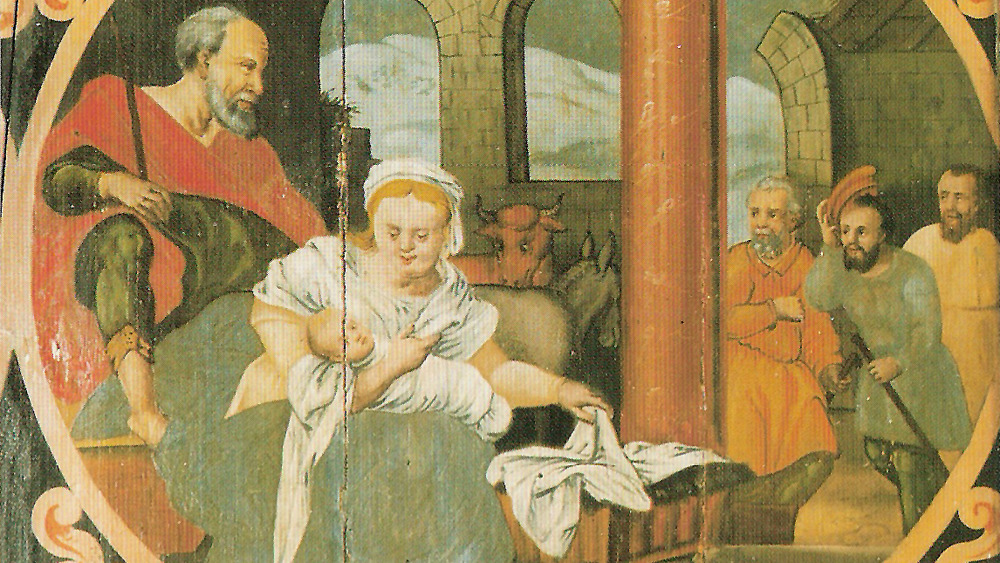

The central importance of the ox and donkey to the Nativity scene

The biblical narrative makes no mention of any animals being present at the moment of Jesus' birth, despite his being laid down in their feeding trough. Still, any Nativity scene worth its salt has a smattering of animals throughout the stable scene, usually some cows and donkeys and sheep and who knows what else. The tradition of animals in the Nativity scene isn't new, of course. In fact, as Professor Brandon W. Hawk points out, one of the earliest depictions of a Nativity scene that we have–on a Roman sarcophagus from the 4th century–features an ox and a donkey and no Mary and Joseph. To early Christians, the flanking of the Child Jesus by these two specific animals was central to the imagery of the Nativity, more so even than Jesus' parents. Why?

Well, as with many details of Jesus' birth, it was seen as the fulfillment of prophecy from the Hebrew scriptures. In this case, the prophet Isaiah said, "The ox knows its owner, and the donkey its master's crib; but Israel does not know, my people do not understand." The imagery of these two animals kneeling shows the animal kingdom as more reverent of God than his own rebellious people. Additionally, the kosher ox and the unclean donkey were thought to represent, respectively, the Jewish and Gentile nations who would come to bow to him as well.

Animals spoke at the birth of Christ

While the Bible doesn't record any specific animals being present at the birth of Christ and early tradition added an ox and a donkey, by the Middle Ages there was no shortage of animal-based legends applied to the moment of Jesus' birth. The 12th century Christmas carol "The Friendly Beasts" records donkeys, cows, sheep, and doves proudly recounting their contributions to the baby Jesus' comfort, but the Free Dictionary lists a number of legends that outstrip even these small animal actions. In one story, a robin spent all night fanning the flames of the Holy Family's fire with his wings, and that's why his breast is famously red. A stork padded Jesus' manger bed with his own feathers, and thus became irrevocably associated with babies and birth. A nightingale sang along with the angels and was rewarded with the sweetest song of all the birds. An owl failed to follow the other birds to the stable and has been cursed ever since to ask, "Who? Who will lead me to the Christ child?"

One extended story involves a series of animals announcing the birth of Christ with animal sound puns that really only work in Latin, like a rooster shouting "Christus natus est!" ("Christ is born"), which has the same cadence as "cock-a-doodle-doo!" Then a cow moos "uuuuuubi?" ("Where?") and a sheep bleats "Beeeeeeethlehem." You get it. It's cute.

A woman lost a hand for doubting Mary's virginity

In the Infancy Gospel of James, after Joseph walks through a bunch of time-frozen birds like Neo dodging bullets in The Matrix, he manages to find a midwife and bring her back to Mary. When the two return, they find the cave in which Joseph had left Mary surrounded by a magic glowing cloud. When the midwife marvels at this sight, the cloud dissipates and is replaced by a flash of light that's unbearable to look at. When the light finally dims, it reveals Jesus has been born and is nursing at Mary's breast. The midwife is so amazed, she runs out of the cave and tells her friend, another midwife named Salome, the buck wild things she has just seen, the products of a virgin birth.

Salome is incredibly skeptical at the concept of a child born of a virgin and decides to check things out for herself. She marches into the cave where Mary and the baby are and immediately thrusts her hand, you know, down there, looking for physical evidence of Mary's virginity. She quickly withdraws her hand in pain, as her hand has been burned off. She repents of doubting God's miracles, and an angel appears who tells her she is forgiven and she should go touch the baby. As soon as she does, her hand is healed.

Creating the Three Kings

The Gospel of Matthew doesn't tell anything of the circumstances of Jesus' birth, but he does lay out what happens a little later: some wizards from Persia come to visit him. They give him gold, frankincense, and myrrh and then go away. That's all the details we get, but in the centuries since the composition of Matthew, these strange Persian wizards have been refined into the Three Kings we know so well from the one song. As Professor Brandon W. Hawk points out, the biblical account does not tell us there were three of them or that they were kings, but these points have been inferred from their three costly gifts, and the idea of foreign kings bowing to the King of Kings is an appealing one.

In the ensuing years, a number of details have been added to the Magi's biographies, including traditional names (Caspar/Gaspar/Jasper, Melchior, and Balthazar are the most common, but there are tons of variations), ages (one young, one middle aged, and one old), and geographic origins (one from Europe, one from Asia, one from Africa). By the time of a medieval legend called the Historia Trium Regum ("History of the Three Kings") by a monk named John of Hildesheim, they were magical astrologers with a headquarters on the Hill of Vaws who were baptized in India by the apostle Thomas before ending up in Germany somehow.

Baby Jesus' impossibly heavy stone crib

One text that briefly expands on the story of the visitation of the Three Kings to the infant Jesus is a medieval narrative found in Turkey known as the Adoration of the Magi, which starts by following the biblical story as laid out in the Gospel of Matthew: the Magi want to go worship the majesty indicated by the presence of the great Star of Bethlehem and King Herod tries to trick them into betraying the location of Jesus. They stop at the place where the Star pauses in Bethlehem and find the baby Jesus, to whom they present their gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. All normal Bible stuff at this point.

Then it gets kind of strange. The baby Jesus, after speaking to them in a regular person voice thanking them for their gifts representing his role as king, god, and healer, reaches over and breaks a chunk off of his stone cradle like someone tearing off a hunk of bread. He then gives it to the Three Kings as a thank you gift, but they find the piece of rock is too heavy for them to carry. They load it onto a horse, but the horse can't carry it either. Then a well opens up suddenly, so they throw the crib piece down there, and the well explodes with magical fire. This is supposed to explain why Persian wizards like fire.

The tree that bowed to Mary and Jesus

One of the most popular apocryphal texts on the birth and childhood of Jesus was the 7th century Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, which compiled the stories of older Greek infancy gospels like those of James and Thomas and translated them into Latin, which helped its popularity in Latin-speaking Western Europe. While this narrative repeats a lot of the details from the Infancy Gospel of James concerning the birth and childhood of Mary and the Nativity of Jesus, including the midwife getting her hand burnt off by Mary's bathing suit area, it adds some original touches as well. Notably, after Jesus is born and the Holy Family is on their way to Egypt to escape King Herod, baby Jesus tames a cave full of dragons.

One anecdote from this text was adapted later into the 15th century Christmas carol known as "The Cherry Tree Carol." The story goes Mary and Joseph were passing by some fruit trees (originally a date palm, a cherry tree in the carol, obviously) and Mary asks Joseph for some fruit. An uncharacteristically grumpy Joseph says, "Why don't you ask the father of your baby to get you some fruit?" At which point Jesus, either a baby or still in utero depending on the source, commands the tree to bend down and give Mary its fruit, which of course it does.

Christmas led to the murder of thousands of toddlers, maybe

The flip side to the cool part of three foreign wizard kings coming to bring baby Jesus expensive gifts for his birthday is that a famously cruel king wanted to kill him when he learned the King of Kings had been born. This leads to the passage of the Christmas story known as the Massacre of the Innocents, which, in a parallel to the life story of Moses, sees Herod the Great issuing a decree that all boys in Bethlehem two years and under should be killed. How many babies might that be? Well, setting aside the fact most modern scholars say there is no evidence a Massacre of the Innocents ever happened at all, population and demographic evidence of Bethlehem in the time of Herod suggests somewhere between seven and 20 babies and toddlers. By comparison, the Catholic Encyclopedia says the traditional liturgy commemorates the death of 14,000 babies in Herod's massacre and medieval authors enumerate as many as 144,000. So, you know, somewhere between seven and 144,000.

As the Encyclopedia Britannica explains, these slaughtered infants are remembered as the first martyrs, and their feast day, known as the Feast of the Holy Innocents or Childermas, is on December 28. In some countries, this day is celebrated by putting children in charge for the day, or it's a day for April Fools' Day-like pranks, with the victims known as the "innocents."