The Untold Truth Of The 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival

The summer of 1969 was a particularly historic time for the United States. Neil Armstrong landed on the moon. Troops were sent home from Vietnam. And hippies danced to folk and rock 'n' roll at Woodstock. But 100 miles from Woodstock was another major cultural event that, until recently, many people had never heard of: the Harlem Cultural Festival, known colloquially as "Black Woodstock."

From late June to late August, hundreds of thousands of people swarmed to 135th Street in Harlem to attend the free festival. They saw some of the biggest acts of the time, including Stevie Wonder, Sly & The Family Stone, The 5th Dimension, and Nina Simone. Two of the major No. 1 songs of the first half of 1969 were not by long-haired Woodstock acts, but by performers at "Black Woodstock": the 5th Dimension's "Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In" and Sly & The Family Stone's "Everyday People."

In other words, the Harlem Cultural Festival was a massive event when it came to popular music, and an even bigger one when it came to Black culture. So why was the event all but forgotten for so many decades? Here's more on the historic event that history forgot.

A minor celebrity named Tony Lawrence started it all

In 1967, the New York City Parks Department hired a man named Tony Lawrence to organize summer events in Harlem. For the previous decade or so, Lawrence had been an entertainer with a flair for both singing and acting. According to Rolling Stone, he sang R&B- and soul-infused songs in several languages for an obscure New York record label. "Tony's biggest aim is to become a movie star, which is probably the only career that can eventually support his expensive appetite for flashy sports cars, sleek motor boats, and extensive worldwide travel," read a 1961 newspaper article about Lawrence (via Rolling Stone).

In the 1960s, Lawrence began working on community projects. Using his minor celebrity status, he raised funds for youth facilities and programs as the Youth Director of a Harlem church. In May 1967, he and the New York Parks director announced plans for the Harlem Cultural Festival, which would be, in Lawrence's words, "about where the negro lives, physically and spiritually."

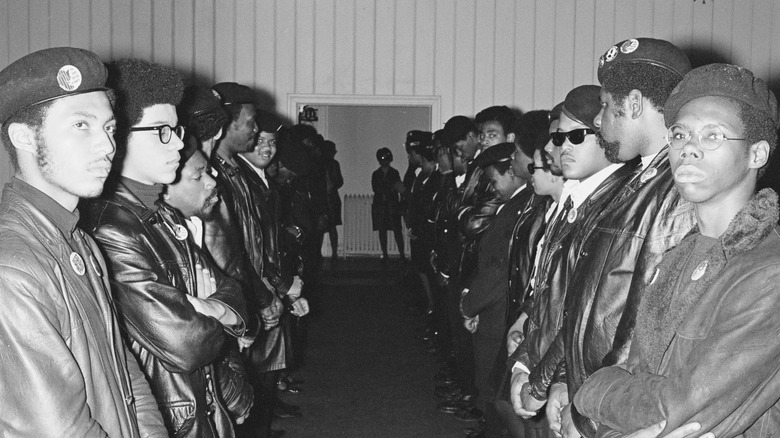

The Black Panther Party provided security

The 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival took place the year after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated and the summer before Black Panther revolutionary Fred Hampton was assassinated. According to Blavity, the Black Panther 21 trial was underway at the time after 21 members of the Black Panther Party were accused of planning to bomb buildings, attack police departments, and murder police personnel in New York City. (They were later acquitted of all charges, per The New York Times.) Grief and unrest infiltrated the African American community, and the relationship between the community and the police was as shaky as ever.

For the first day of the festival — June 29, when Sly & the Family Stone played — the New York Police Department refused to provide security, per Smithsonian. So the Black Panther party took matters into their own hands and provided security. According to the documentary "Summer Of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)," some party members wore their uniforms, while others wore plain clothes, and they spread out across the festival grounds, some sitting up in trees to oversee the show. The NYPD eventually showed up, but the Panthers stayed put to make sure the Black community was sufficiently protected. "Nobody ever heard of the Harlem Cultural Festival," said Cyril "Bullwhip" Innis Jr., who was part of the Black Panther security team (via the L.A. Times). "Nobody would believe it happened."

It was more than a music festival — it was a political and cultural event

With all that was going on in and around 1969, particularly in the African American community, that summer seemed the optimal time for a celebration of Black culture. "You see the generations teetering," said director and producer Morgan Neville, who helped develop the documentary "Summer of Soul" (via Smithsonian). "The tension between soul and funk, civil disobedience versus Black Power, the tension of Harlem itself at the time."

Several of the performers at the festival seized the opportunity to make political, or generally empowering, declarations onstage. "You'd go for a job and you wouldn't get it," said Roebuck "Pops" Staples during the Staples Singers' performance (via Smithsonian). "And you know the reason why. But now you've got an education. We can demand what we want. Isn't that right? So go to school, children, and learn all you can. And who knows? There's been a change, and you may be president of the United States one day."

Activist and politician Jesse Jackson also spoke at the festival. "As I look out at us rejoice today, I was hoping it would be in preparation for the major fight we as a people have on our hands here in this nation," he said (via Smithsonian). "Some mean stuff is going down. A lot of you can't read newspapers. A lot of you can't read books because our schools have been mean and left us illiterate or semi-literate. But you have the mental capacity to read the signs of the times."

Tony Lawrence made several allegations against the event's white promoters

Following the Harlem Cultural Festival, Tony Lawrence remained elusive throughout his life. "We would say, 'Where is Tony? We haven't seen Tony in weeks. Where is he?'" said Allen Zerkin, who was Lawrence's assistant at the Parks Department in 1967 (via Rolling Stone). "And then he would just show up, and you never knew where he had been or what he had been up to."

Then, in 1972, Amsterdam News published several articles in which Lawrence made allegations against those he had done business with for the Harlem Cultural Festival. One of the articles stated that Lawrence was "suing his former white partners in promoting the festival for $100 million for fraud." He claimed that his business partners Harold Beldock and Jerrold Kushnick had taken hundreds of thousands of dollars that were supposed to go toward the festival. Everyone involved in Lawrence's allegations denied his claims, and Beldock told Rolling Stone that they were "outrageous."

Lawrence also claimed that he had been threatened by a "mafia enforcer" and that someone had tried to murder him by blowing up his car, per Rolling Stone. The Amsterdam News ultimately admitted that "attempts to substantiate Lawrence's charges against the parties mentioned ... proved inconclusive." The case was reportedly brought to the New York District Attorney's Office before ultimately being dropped.

Questlove made a documentary about the festival because 'no one cared'

In 2021, Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson released his directorial debut, the documentary "Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)." The documentary included clips excavated from 40 hours of live footage from the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, which had gone unseen for five decades, per The New York Times.

When he first heard about the festival, Questlove questioned how such a major musical and cultural event could have flown under his radar. "Instantly, the music snob in me said, 'I've never heard of that,'" he told The New York Times. "So I looked it up online. It's not on the internet, so I was highly skeptical. But, when they finally showed me the footage, I ... thought, 'Oh God, this really did happen.' For nearly 50 years, this just sat in a basement and no one cared. My stomach dropped."

Questlove also questioned how modern culture — and Black culture, in particular — might have been different had the Harlem Cultural Festival been featured in the history books like Woodstock was. "Why was it that easy to dispose of us?" he said. "Instead, the cultural zeitgeist that actually ended up being our guide as Black people was 'Soul Train.' And so, I'm always going to wonder, 'How could this and 'Soul Train' have pushed potential creatives further?'"